World mourns civil rights hero – Julian Bond

First SPLC president dies at 75

MONTGOMERY, Ala. – Just blocks from where slaves were once auctioned and near the spot where Rosa Parks started her ride into civil rights history, Julian Bond stood to address a crowd of 6,000 who had gathered to dedicate a memorial to those who died during the struggle for equality.

It was Nov. 5, 1989 – nearly a quarter century after the Voting Rights Act was enacted. Bond knew the job wasn’t finished.

The Civil Rights Memorial, he said “bears the names of 40 men, women and children who gave their lives for freedom. It recalls their individual sacrifice. And it summons us to continue their collective cause.”

That collective cause – the continuing march for justice – was the driving force behind Bond’s journey from a charismatic, young civil rights activist to one of the nation’s most beloved statesmen.

It was the same cause that led him to become the SPLC’s first president, a post he held from 1971 to 1979 before spending the rest of his life as a board member.

When Bond died on Aug. 15 at age 75, not only did the nation lose a civil rights legend, the SPLC lost a great friend and inspirational colleague.

“With Julian’s passing, the country has lost one of its most passionate and eloquent voices for the cause of justice,” said his friend and colleague, SPLC founder Morris Dees. “He advocated not just for African Americans, but for every group, indeed every person subject to oppression and discrimination, because he recognized the common humanity in us all.”

Teacher, author, poet

In the days after Bond’s passing, tributes poured in from political and civil rights leaders who mourned the death of one of the most iconic figures of the movement, a man who went on to become a teacher, author, poet and longtime chair of the NAACP.

President Obama called Bond a “hero” who “helped change this country for the better.” Former Attorney General Eric Holder hailed him as a “great man who made the gains of the next generation possible.”

“Julian was so smart, so gifted, and so talented,” said U.S. Rep. John Lewis, who worked with Bond as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the early 1960s. “He was deeply committed to making our country a better country.”

The SPLC’s relationship with Bond began in 1971, when Dees asked him to be the fledgling organization’s president. Both men recognized the need to ensure that the promise of new civil rights laws would become a reality – because change was coming slowly to the heart of Dixie.

“We needed lawyers who would file the cases that would implement these laws,” Bond said in 2012. “Back then, most lawyers were reluctant to take on civil rights cases."

Morris’ proposal for the SPLC promised a way to provide desperately needed civil rights attorneys.

During the early years, the SPLC focused heavily on demolishing remnants of Jim Crow. Its cases integrated bastions of white supremacy such as Alabama’s state trooper force and legislature. At the same time, the SPLC challenged numerous discriminatory policies, such as the forced sterilization of thousands of black teenage girls and the placement of homeless black children in detention facilities.

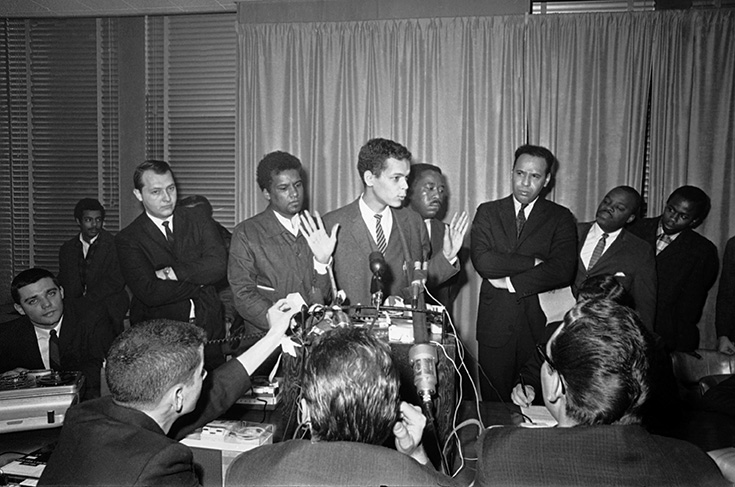

Bond knew the fight for justice could be difficult. After his election to the Georgia House of Representatives in 1965, white legislators refused to seat him. He was accused of disloyalty for opposing the Vietnam War. It took a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1966 for Bond to be seated.

“Julian was always critical to our success,” said SPLC President Richard Cohen. “He was there at the beginning. And he was there for us recently when he consulted on our film about the struggle for voting rights – because he was outraged that the rights so many had fought for were now being eroded.”

Bond also was the narrator for the SPLC’s Oscar®-winning documentary A Time for Justice, as well as the Academy Award-nominated Shadow of Hate.

When a 2011 SPLC report found most states fail at teaching the movement, it was Bond who wrote the foreword. “At the University of Virginia, my students are often outraged to learn that they have never been taught about events in their own hometowns,” he wrote. He added that the movement “is a history that continues to shape the America we all live in today.”

Hero for all

But Bond’s sense of history did not blind him to the inequities of the present. He remained a voice for justice for all, speaking out eloquently for LGBT rights in recent years.

In Bond’s last hours, he continued to touch the lives of those around him. The tribute that may best sum up his legacy came from a nurse who treated him just before his death.

“She said, ‘As a gay American, I thought he was a hero,’” said Bond’s wife, Pamela Horowitz, a former SPLC attorney.

A Life of Service - A Timeline of Julian Bond's Life

Jan. 14, 1940

Born to librarian Julia Agnes and university president Horace Mann Bond in Nashville, Tennessee.

1957

Enters Morehouse College in Atlanta.

April 17, 1960

Helps form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Morehouse College.

January 1961 – September 1966

Serves as communications director of SNCC, leading student protests against segregated public facilities and Jim Crow laws in the Deep South.

June 1965

Elected to the Georgia House of Representatives by a vote count of 2,320 to 487.

Jan. 10, 1966

Georgia House votes 184-12 not to seat Bond because he publicly opposes the Vietnam War.

Dec. 6, 1966

The U.S. Supreme Court rules 9–0 in the case of Bond v. Floyd that the Georgia House of Representatives had denied Bond his freedom of speech and was required to seat him.

Jan. 9, 1967

Is sworn in and takes his seat in the Georgia House of Representatives where he organizes the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus and serves until 1974.

Aug. 29, 1968

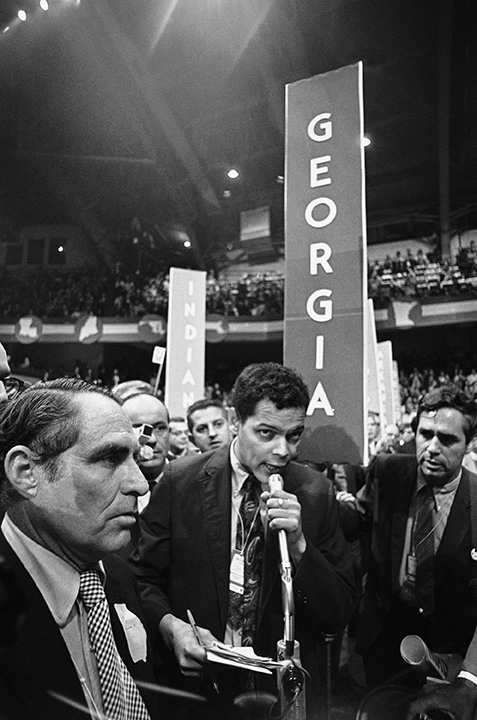

Nominated for vice president at the Democratic National Convention. He declines the nomination because, at 28, he is seven years shy of the age requirement.

1971

Returns to Morehouse College to earn a degree in English. He is eventually awarded 21 honorary degrees from various colleges and universities.

1971 – 1979

Serves as president of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Bond remains involved in the SPLC and serves on its board of directors until his death.

1974 – 1987

Elected for six terms to the Georgia Senate. He retires to run for Congress, but loses the election to John Lewis.

1974 – 1989

Serves as president of the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP.

1992 – 2012

Is a popular history professor at the University of Virginia, making civil rights accessible to his students.

1998 – 2010

Serves as national chair of the NAACP.

2002

Accepts the National Freedom Award from the National Civil Rights Museum.

Aug. 15, 2015

Julian Bond dies at the age of 75.