Florida sets up formerly incarcerated people to vote — then arrests them

In a country where wealth and friends in high places can go a long way in making legal problems disappear, John Boyd Rivers has neither of those advantages.

He and his wife barely scrape by in Alachua County, Florida, raising eight children on his unreliable income as a mason.

On May 16, Rivers, 45, stood before a Gainesville court and explained why he thought he had the right to vote in the 2020 presidential election after a representative of the county elections office helped him register and he received a Florida voter ID card.

“I informed him that I was in [the Alachua County jail] on a violation of probation and he [elections official] told me that as long as I didn’t have a sex crime or murder charge, I would be eligible to get my rights restored,” Rivers told the jury.

He was among 41 formerly incarcerated people, also known as returning citizens, who were arrested in 2022 and 2023 for voter fraud in Florida following the 2020 election. Nearly half took plea deals, fearful of facing the unknown of a jury trial and guilty verdict. To date, only Rivers and one other have been tried in court. He drew a split verdict: not guilty of knowingly registering to vote while ineligible but guilty of willful, fraudulent voting.

Gov. Ron DeSantis and conservative lawmakers have launched continued attacks on voting rights that have made the state’s historically inequitable criminal justice and voting rights systems worse. Since DeSantis’ election in 2018, the Florida Legislature has passed the most sweeping voter suppression laws of any state. DeSantis has proposed additional voter suppression measures for 2024 and continues to ramp up spending for his Office of Election Crimes and Security – from $1.2 million in 2022-2023 to $2.2 million in 2023-2024. And he’s added $1 million in new spending for the establishment of a Statewide Voter Fraud and Assistance Hotline.

“Instead of fulfilling its role to enable Floridians to vote, the state has made it more difficult, which is anti-democratic,” said Courtney O’Donnell, a senior staff attorney for voting rights with the Southern Poverty Law Center.

These new laws criminalize voting – particularly by returning citizens – and the third-party voting organizations that assist Black people and other historically disenfranchised groups to register to vote due, in part, to their lack of access to ballot boxes.

“Florida continues to attack returning citizens who simply want to exercise their right to vote as well as disregard the majority of Floridians who support that right,” O’Donnell said. “We are continuously monitoring these developments, and along with our community partners, we are fighting back to uphold voting rights in Florida.”

Impossible debt

Florida leads the country by far in disenfranchising U.S. citizens. Nearly 1.2 million people cannot vote due to a felony conviction, according to the Sentencing Project. Considering that Black people are arrested at five times the rate of white people and in 2021 made up 48% of the state’s prison population while only 14% of the overall state population, it is unsurprising that one in eight Black Floridians of voting age were disenfranchised in 2022. That rate is nearly twice that of non-Black Floridians.

At the time Rivers registered to vote, he knew nothing about the 2019 voter suppression law, SB 7066, that directly impacted him and the 40 other returning citizens who have faced charges.

SB 7066 requires returning citizens not only to complete their sentences in full but also to pay all fines, fees and restitution to their victims. These court, interest and collection fees are compounded for delinquency of payment and can easily run into the thousands. Many returning citizens are simply unable to pay.

At the time of his voting trial, Rivers had paid just $34 of his more than $6,700 in fines, fees and restitution. Rivers is on a two-year supervised probation, for which he must pay $20 each month on top of his court debt.

He plans to appeal his conviction with the help of a public defender.

If impossible debt weren’t obstacle enough, the state’s online system for returning citizens’ voter qualification lacks a central database of convictions and total debt owed, making it virtually impossible to figure out what an individual’s outstanding financial obligation is. The state acknowledges the system’s failures but does nothing to fix them.

SB 7066 made a mockery of Amendment 4. The 2018 ballot measure that was approved by 65% of Florida voters gave returning citizens the right to vote unless they had committed murder or a sexual offense. It was a dream come true for returning citizens – until election crimes task force officers began going door to door with guns raised to arrest the very people Amendment 4 was intended to re-enfranchise.

Rivers had been convicted of four felonies, two false statements and a probation violation over the course of 14 years. Like most returning citizens, he had completed his sentences in full and was “excited,” he said, at the prospect of voting in the 2020 election.

The day he registered to vote from jail in Alachua County, Rivers glanced over an information pamphlet and a voter registration form. Both were printed in 2013, six years before SB 7066 was enacted. The state allowed county elections supervisors to use obsolete voter registration forms and pamphlets, ones never updated with the fines, fees and restitution obligation. Rivers signed the registration and assumed that the information he provided would be checked.

By law, the state Division of Elections is required to perform a legal analysis to determine if a returning citizen is eligible to vote and send its conclusion to the elections supervisors of all 67 Florida counties. Only after the local official double-checks the information is a voting ID card supposed to be issued.

The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC), a nonpartisan nonprofit that has been helping returning citizens restore their right to vote, has been working with formerly incarcerated people on this situation.

“We knew [the arrests] were a sign of things to come because all of them [returning citizens] received a voter registration card,” said Desmond Meade, founder of the FRRC. “We didn’t focus on the charges but on the fact that they never should have been issued a voter card. The election system is broken.”

Nicholas Nunn, the FRRC senior counsel, agreed.

“Instead of helping returning citizens understand their eligibility, Florida expanded the office of the statewide prosecutor to prosecute them,” Nunn said.

In Rivers’ case, he told the court that the elections office representative he met with, Thomas “T.J.” Pyche, never mentioned SB 7066, and Pyche could not remember with absolute certainty whether he had.

“He made an announcement several times [at the jail] … said they passed Amendment 4 and people with felonies could possibly vote if they were, if, you know, if they were approved to do so,” Rivers recalled.

State investigation

On July 28, the FRRC filed the first major lawsuit challenging Florida’s implementation of SB 7066. The suit argues that Florida’s failure to provide an accessible, accurate system for determining voter eligibility – namely a returning citizen’s financial obligation – makes it “impossible to determine voting eligibility,” the basic requirement of SB 7066 and the state’s own representation of its obligation during a prior lawsuit against SB 7066.

The new lawsuit also asserts that DeSantis’ threats to prosecute more returning citizens who relied on voter information cards to cast their ballots have effectively scared off people from voting in the future. As a result, the state has created an “undue burden” on the right to vote in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

Nunn, calling Florida’s online voter verification system “a national embarrassment,” said “the state cannot make you guess as to your voting eligibility and then arrest you when you guess wrong.”

Steve Cary, another legal counsel for the FRRC, said, “Voter fraud cases are the first of their kind [against] people who believed that Amendment 4 gave them their right to vote.”

The FRRC wrote the first draft of Amendment 4.

Voters represented in the lawsuit, Cary said, “are exhausted and confused. They’ve been through the wringer over something they didn’t even know was wrong.”

In Rivers’ case, he did not learn the truth until nearly a year after he voted.

The revelation came after the Florida Department of Law Enforcement in 2022 launched a criminal investigation of the Alachua County Supervisor of Elections office, run by Democrats, over its efforts to sign up people in jail to vote. An investigator later described “the mass registering of inmates to vote without any inquiry into the person’s prior criminal history, proof of identity, satisfaction of prior legal financial obligations, restoration of voting rights, the charges they were being held on (or) their knowledge level and understanding of the state’s voting system and requirements.”

The local prosecutor, a Republican, cleared officials in the elections office of wrongdoing but filed felony voter fraud charges against 10 people who had been incarcerated in the jail.

‘Came to his house with guns’

In an interview with the SPLC, criminal defense attorney Robert Barrar described Florida’s voter fraud prosecutions as “a colossal waste of taxpayer dollars.”

Barrar successfully defended returning citizen Ronald Miller in Miami-Dade County and is defending him against the state’s appeal.

“The county prosecutor didn’t take the [Miller] case,” Barrar said. “It was the state prosecutor under the Florida attorney general, so this is all political theater.”

Miller, who had been convicted of murder in 1998, served his sentence and was solicited to register to vote by a Democratic voter outreach operative outside a Miami grocery store. He signed his name and filled out his address on a voter registration form given to him by the operative, who filled out the rest. Like the others, Miller received a voter ID and assumed he could vote in the 2020 presidential election, although in his case, his murder conviction made him ineligible.

“The FDLE agents came to his house with guns, and he comes out of his house in his boxers and is arrested,” Barrar said.

“When I read about the arrests, it appalled me, so I decided to represent him pro bono. … The charging document says that the voter has to have specific intent to commit fraud, and I didn’t see it. There can be no fraud when someone is issued a voter registration card and votes thereafter, believing they had the right to.”

Legacy of Jim Crow

Following the Civil War, Florida officially disenfranchised Black Floridians with felony convictions in 1868, when it wrote a new state constitution that prohibited persons convicted of a list of felonies to vote.

In the following decades, as Reconstruction ended and Jim Crow spread across the former Confederate states, similar laws kept Black people segregated and powerless until passage of new civil rights and voting laws in the 1960s.

In recent years, conservative lawmakers in numerous Southern states have tried to turn back the clock by passing restrictive laws that effectively block many citizens in historically disadvantaged communities from the polls.

In Georgia, the Election Integrity Act of 2021, SB 202, criminalized a broad range of voter-assistance activities by individuals and organizations.

In Alabama, returning citizens must pay their fines, fees and victim restitution and apply for a certificate that shows that their right to vote has been restored. Under the 2017 Definition of Moral Turpitude Act, HB 282, if they have been convicted of certain crimes, they face a higher bar for rights restoration.

In Mississippi, lawmakers this year passed the voter-purging law HB 1310. They also passed SB 2358, a law that criminalized voter assistance in the return of absentee ballots. A federal judge in July blocked SB 2358 as a violation of the Voting Rights Act after the SPLC, ACLU, ACLU Mississippi and the Mississippi Center for Justice sought a preliminary injunction against it.

On Aug. 4, the SPLC also won a major voting rights victory when a judge ruled that the 1890 Mississippi Constitution’s lifetime voting ban for returning citizens convicted of certain felonies violates the Eighth Amendment.

The jelly bean test

Yet Florida stands out for its recent efforts to suppress voting.

In addition to SB 7066, the state passed SB 90 in 2021 and SB 7050 this past May. Together, they placed new voting barriers that disparately affect people of color and the third-party voter registration organizations that assist them.

Because Black people register to vote with these organizations at five times the rate of white people, the severe strictures SB 7050 places on them threaten not only the very existence of these groups, which may number as many as 2,000, but the significant number of Floridians they register and assist to vote in elections.

Faith in Florida is one of those groups. It provides voter education, registration and voting assistance in 25 of Florida’s 67 counties, with an emphasis on reaching Black and Brown communities in rural areas. The group registered 5,000 people to vote in 2022.

“We have to be extremely careful now in how we collect voter registrations and turn them in,” said LaVon Bracy, Faith in Florida’s democracy director. “A $250,000 fine in one calendar year?” she asked, referring to the jump from the maximum $50,000 in fines that can be levied in one year. “Nonprofits don’t have that kind of money.”

Under the new law, groups like hers can be fined $50,000 for each person who is found to be ineligible to collect voter applications. They will also be required to give a state “receipt” to every person they register. The receipt must include their name and the name of the group that registers them. The group sends the receipt to the state, which is then supposed to investigate the eligibility of the applicant.

“We’ve gone back to Jim Crow,” Bracy said. “We don’t have to count jelly beans to get Black folks not to vote. They’ve gotten smarter with their tactics, but the object is the same, voter suppression.”

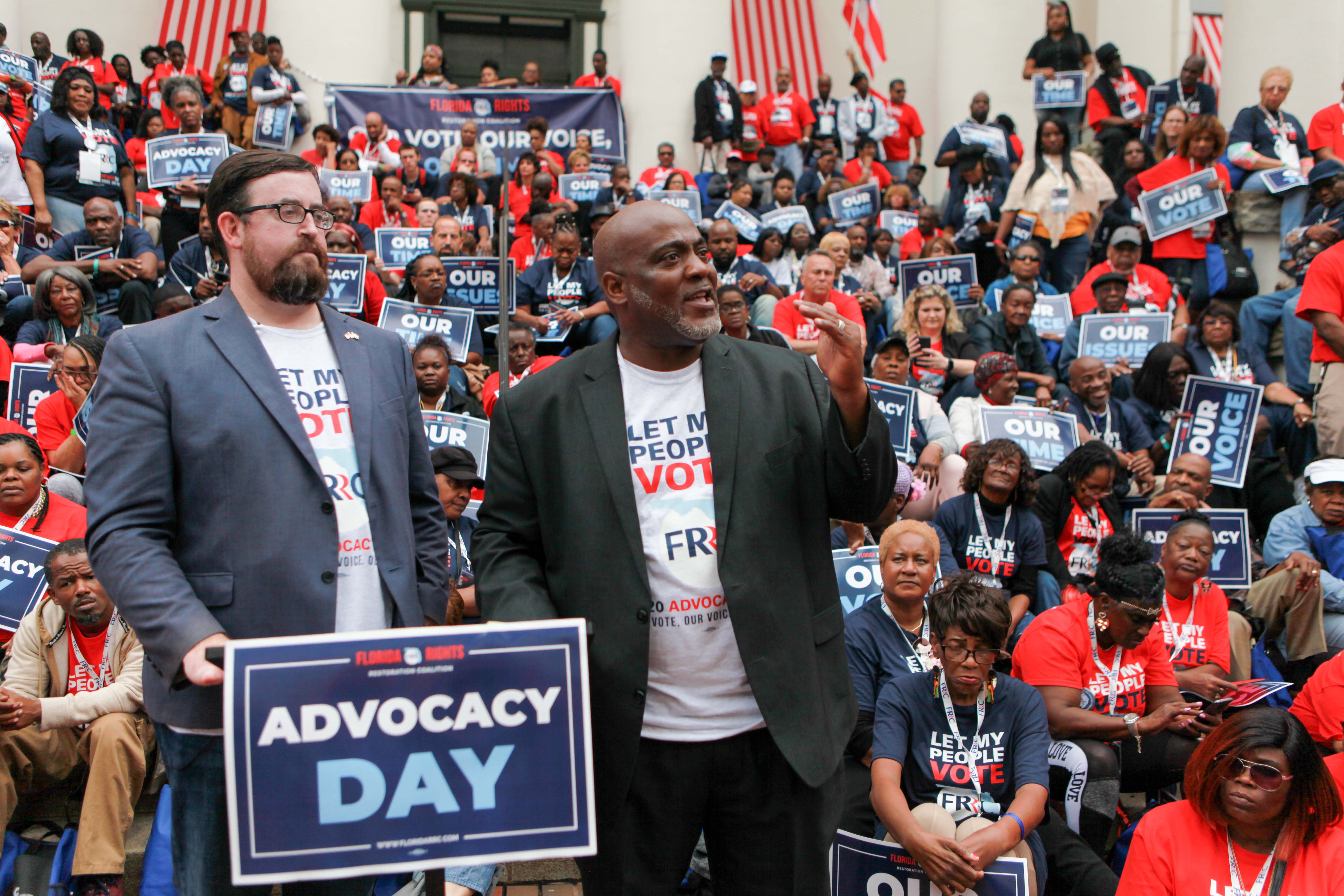

Photo at top: In a photo from Feb. 18, 2020, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition holds its Annual Advocacy Day in Tallahassee. (Credit: Brandi Hill)