St. Mary Congregational Church is a small worship center on Louisiana Street just outside downtown Abbeville, Louisiana. Unlike the massive St. Mary Magdalen Catholic Church a few blocks away, the simple, wood-framed building fits snugly into the middle of the neighborhood block, with only its bright white paint and steeple giving its presence away.

Attendance among the primarily Black congregation was light on July 13, with about two dozen parishioners in attendance. But the church was only one of several stops that morning for Vermilion Parish NAACP President Linda Williams Cockrell. She was getting the word out to residents about the upcoming Abbeville City Council meeting and the potential end to years of litigation over the redrawing of the city’s voting district map.

The issue at hand was inequality in the size of the city’s four council districts. Because the council did not make any adjustments based on the 2020 census, population shifts created a disparity between some, with a difference of up to 19.3% in population between districts. That imbalance gives greater voice to the voters in the smaller, majority-white districts.

“We are all in this together,” Cockrell said. “It’s one fight and, if we fight together for what is right, we will be successful.”

Vermilion NAACP representatives had a list of church services to attend to deliver that message. As Sunday wore on, a half-dozen church congregations would hear the message and the call for a community meeting the next day to educate voters.

“We’re talking about the constitutional requirement of one person, one vote, which means everybody’s vote should count equally,” said Rose Murray, a senior staff attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Democracy: Voting Rights litigation team who also attended services in Abbeville that day. “In order for everybody’s vote to count the same, the populations in different single-member districts should be as even as possible.”

It’s a larger issue for Abbeville’s Black residents, who make up about 43% of the city’s population. Only one district is majority Black — District D, the second-largest, with 2,846 residents. But the district’s total population is more than 70% Black, much higher than the overall percentage for the city. The SPLC filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Vermilion Parish NAACP chapter in October 2023. After the suit was filed, Abbeville saw one of its council members elected in a special election with a one-vote margin of victory, emphasizing the need for equal and ethical district maps.

‘Dilution of the Black vote’

Although the U.S. Constitution requires a census every 10 years to determine how seats in the U.S. House of Representatives are apportioned, it does not direct how that census should affect local redistricting. Those guidelines have been set through federal laws, like the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — which went into effect nearly 60 years ago — state laws and in constitutional amendments, specifically the 14th Amendment.

After the 2020 census, the Abbeville City Council decided not to redistrict. In 2022, it voted unanimously to adopt the same map it had been using since the 2010 census, claiming that the city’s population was substantially unchanged and the census data showing otherwise was incorrect. Before that vote, representatives of the Vermilion Parish NAACP and the SPLC presented several maps showing how the districts could be modified to meet the new census numbers.

The council rejected those maps.

After remedial talks in the course of Vermilion NAACP’s lawsuit, the city agreed to go back to the drawing board to propose a redistricting plan. In addition to the original maps that had been suggested, the SPLC attorneys commissioned a refined map that left the four council districts largely intact, with small changes to shift the population between districts. That map achieved almost parity, with about a 1% differential across districts, a difference of about 20 voters from district to district.

Instead, the council had its own map created, one that has a 6.3% differential — a difference of about 200 voters between the largest and smallest districts — and does not address the changes in demographics within the city’s population. That map was passed out of committee at the council’s July 15 meeting and will be up for adoption at a meeting on Aug. 5.

That map leaves District D with a more than 70% Black population — unchanged from the 2010 map — and unnecessarily concentrated. It also leaves the other three council districts with majority-white populations.

“District D, with upwards of a 70% Black population, is frankly a dilution of the Black vote,” Murray said.

She also explained that an opportunity district — one where there is not a clear Black majority, but where the demographic mix allows the Black community to be competitive — would help to make the map more representative of the population.

“Our map doesn’t propose a second majority-Black district,” Murray said. “But we do propose a second Black opportunity district.”

‘As close to fair as we can’

The city’s attorney again floated the theory at the July 15 meeting that the census numbers were flawed and should not be the basis for a voting district map.

“Initially, when this litigation was filed, there was multiple municipalities that said, ‘Hey, look, the census in 2020 for whatever reason is likely not accurate,’” said Jordan Henagan, who represents the city in the lawsuit. “However, as this litigation went on and we were in front of [U.S. District Court] Judge [Robert R.] Summerhays, he indicated that he may not be willing to agree with the argument that the census is not accurate as the basis for keeping the prior map under the prior census.”

According to the Pew Research Center, the 2020 census overall was correct, with some overcounts and undercounts in individual states. Louisiana, however, was not one of them.

The tenor of the committee hearing on July 15 was a sign of how the vote would go. Councilman Brady Broussard Jr. ran things tightly, only allowing committee chairman Tony Hardy the leeway to introduce the discussion before taking back the reins. It seemed like Broussard was going to end discussion before allowing public comment when members of the audience spoke up.

Ravin St. Julien, an Abbeville resident who attended the meeting where the city’s map was passed out of committee, asked Henagan why a more equitable map could not be drawn.

“We saw an election that recently happened that was [decided by] one vote, you know,” St. Julien said. “Let’s get as close to fair as we can. This is a 200-vote-difference map compared to the 20-vote difference map that the NAACP is proposing.”

Henagan said there were other principles that had to be followed but did not directly answer St. Julien’s question.

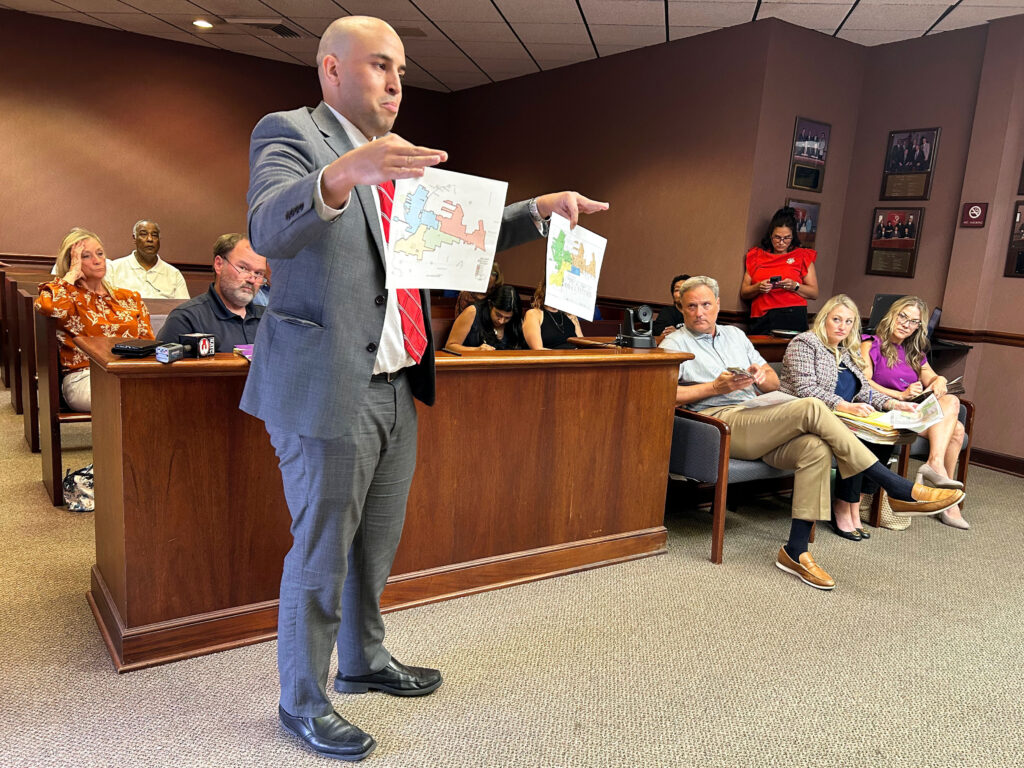

Ahmed Soussi, a senior staff attorney with the SPLC’s Democracy: Voting Rights litigation team, said the map could be drawn — with minimal changes — to not only meet the letter of the law but also provide accurate representation for Abbeville residents.

“One of the things in the Vermilion NAACP map compared to the Abbeville City Council map is there is proportionality,” Soussi said. “It is fair and equitable.”

Soussi defended his stance, laying out the numbers to back up the fairness in the NAACP map districts.

“The reason why it’s imperative to have equal districts is because we just saw a special election decided by one vote,” Soussi said.

The council voted unanimously to move its version of the map forward. That tees up a final vote on the adoption of the map to take place at the regular Abbeville City Council meeting on Aug. 5. Then, once adopted, the map also must undergo court review.

As for the litigation, Soussi said the revised map the SPLC and Vermilion Parish NAACP had proposed would be the best solution, especially since Abbeville is already halfway to its next census — and its next potential redistricting.

“We’re trying to work with the city because we don’t want to continue litigation,” he said.

Image at top: At a committee hearing July 15, 2025, the Abbeville, Louisiana, City Council voted unanimously to move forward on a version of its voting district map that opponents say favors the city’s smaller, majority-white districts. (Credit: Dwayne Fatherree)