A history of protecting society’s most vulnerable.

The SPLC was founded in 1971 to ensure that the promise of the civil rights movement became a reality for all.

By the late 1960s, the civil rights movement had ushered in the promise of racial equality as new federal laws and decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court ended Jim Crow segregation. But resistance was strong, and these laws had not yet brought the fundamental changes needed in the South.

African Americans were still excluded from good jobs, decent housing, public office, a quality education and a range of other opportunities. There were few places for the disenfranchised and the poor to turn for justice. Enthusiasm for the civil rights movement had waned, and few lawyers in the South were willing to take controversial cases to test new civil rights laws.

Alabama lawyer and businessman Morris Dees sympathized with the plight of the poor and the powerless. The son of an Alabama farmer, he had witnessed firsthand the devastating consequences of bigotry and racial injustice. Dees decided to sell his successful book publishing business to start a civil rights law practice that would provide a voice for the disenfranchised.

“I had made up my mind,” Dees wrote in his autobiography, A Season for Justice. “I would sell the company as soon as possible and specialize in civil rights law. All the things in my life that had brought me to this point, all the pulls and tugs of my conscience, found a singular peace. It did not matter what my neighbors would think, or the judges, the bankers, or even my relatives.”

His decision led to the founding of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Dees joined forces with another young Montgomery lawyer, Joe Levin. They took pro bono cases few others were willing to pursue – the outcome of which had far-reaching effects. Some of their early lawsuits resulted in the desegregation of recreational facilities, the reapportionment of the Alabama Legislature, the integration of the Alabama state trooper force and reforms in the state prison system.

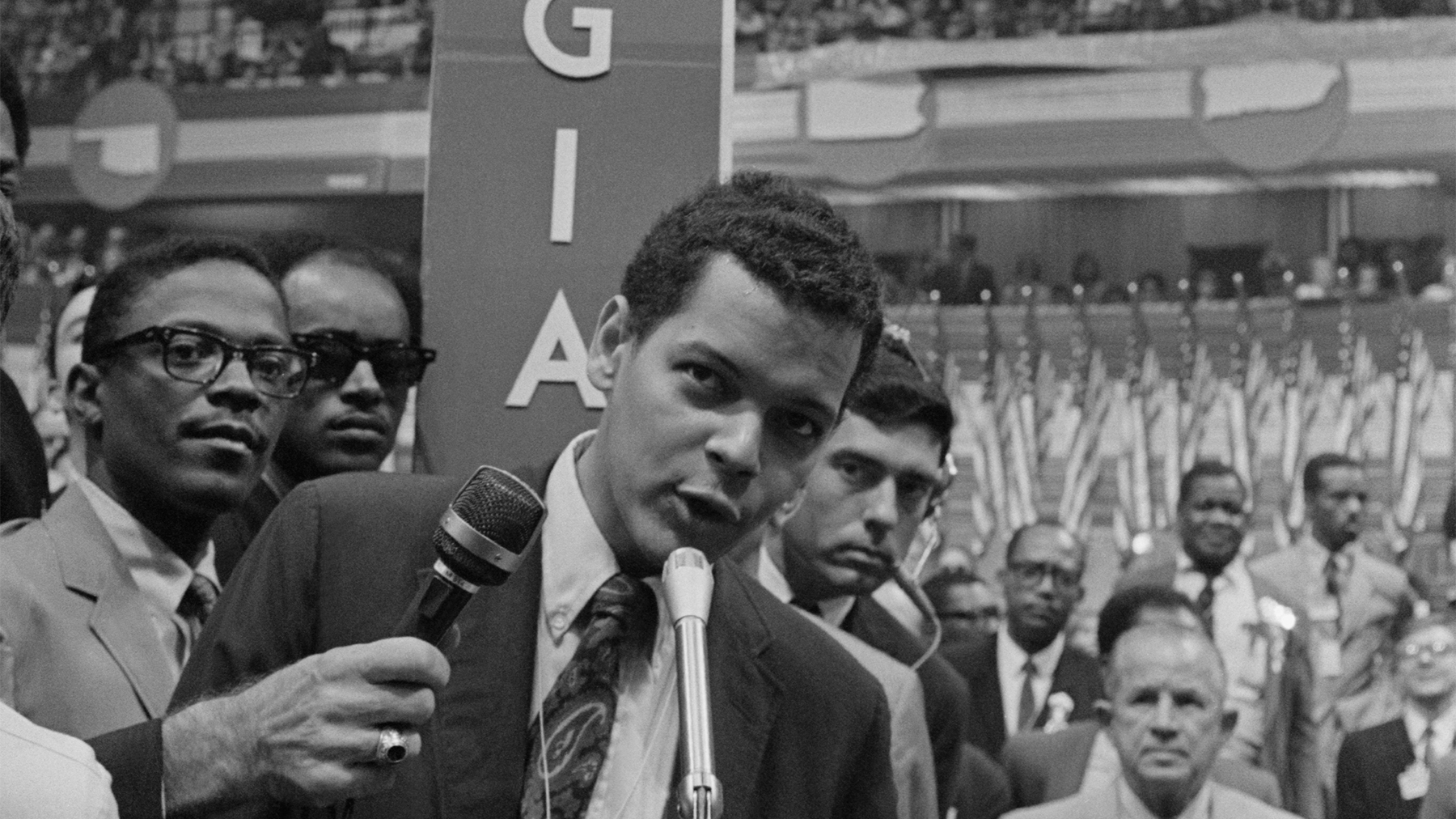

The lawyers formally incorporated the SPLC in 1971, and civil rights activist Julian Bond was named the first president. Dees and Levin began seeking nationwide support for their work. People from across the country responded with generosity, establishing a sound financial base for the new organization.

In the decades since its founding, the SPLC shut down some of the nation’s most violent white supremacist groups by winning crushing, multimillion-dollar jury verdicts on behalf of their victims. It dismantled vestiges of Jim Crow, reformed juvenile justice practices, shattered barriers to equality for women, children, the LGBT community and the disabled, protected low-wage immigrant workers from exploitation, and more.

In the 1980s, the SPLC began monitoring white supremacist activity amid a resurgence of the Klan and today its Intelligence Project is internationally known for tracking and exposing a wide variety of hate and extremist organizations throughout the United States.

In the early 1990s, the SPLC launched its pioneering Teaching Tolerance program (now Learning for Justice) to provide educators with free, anti-bias classroom resources such as classroom documentaries and lesson plans. Today, it reaches millions of schoolchildren with award-winning materials that teach them to respect others and help educators create inclusive, equitable school environments.

As the country has grown increasingly diverse, our work has only become more vital. And our history is evidence of an unwavering resolve to promote and protect our nation’s most cherished ideals by standing up for those who have no other champions.

1970 – A federal court rules that the Montgomery, Ala., YMCA must end its policy of racial discrimination. SPLC co-founder Morris Dees filed the case, Smith v. YMCA, after two black children were turned away from a YMCA summer camp.

1971 – Morris Dees and Joe Levin formally incorporate the SPLC. Julian Bond is named as its first president.

1972 – In Selmont Improvement District et. al. v. Dallas County Commission et. al., the SPLC rectified a 20-year injustice when a federal court ordered the paving of 10 miles of streets in an unincorporated black neighborhood near Selma in Dallas County, Ala. The new streets had to be equal in quality to those installed free in adjacent white neighborhoods in 1954.

1972 – A federal court accepts the SPLC’s reapportionment plan for the Alabama Legislature. It is later affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court. The plan followed the SPLC’s Nixon v. Brewer lawsuit that claimed blacks were underrepresented. Seventeen black lawmakers are elected to the Alabama Legislature in 1974, the first election after the reapportionment plan is adopted.

1973 – The U.S. Supreme Court rules in the SPLC’s favor in the first successful sex discrimination case against the federal government, Frontiero v. Richardson. It rules the Department of Defense cannot grant certain benefits to dependents of servicemen but not to those of servicewomen.

1973 – The Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirms a ruling banning the use of public recreational facilities by segregated private schools in Gilmore v. City of Montgomery.

1974 – Three SPLC clients – Jesse Walston, Vernon Brown and Bobby Hines – are freed in August 1974 following two years in a North Carolina prison after being wrongfully charged with raping a white woman. The three black men, known as the Tarboro Three, faced death sentences.

1975 – SPLC client Joanne Little, a black inmate accused of murdering a white jail guard in North Carolina, is acquitted of murder. The guard was found dead in her cell without his pants. Little said he had tried to rape her.

1976 – A federal court rules Alabama prisons are “wholly unfit for human habitation” in Pugh v. Locke. SPLC attorneys work for more than a decade to force the state to bring the prisons up to constitutional standards.

1976 – The SPLC starts “Team Defense” to develop trial strategies for capital cases and share them with attorneys across the U.S. at seminars and in SPLC-published manuals.

1977 – The U.S. Supreme Court opens the door for women to be hired for law enforcement jobs traditionally held by men after ruling in favor of the SPLC in Dothard v. Rawlinson.

1977 – An SPLC lawsuit challenging sterilization abuse funded by the federal government is remanded to U.S. District Court for dismissal after federal officials withdraw the regulations challenged in the case, Relf v. Weinberger.