Last year, the Georgia Justice Project (GJP) began placing yard signs around the state with a simple message: “Felony sentence complete? You can vote.”

A man driving past a gas station in Conyers saw the sign, pulled over and immediately phoned GJP.

“He’s like, ‘Is this true?’” said Ann Colloton, policy and outreach coordinator for GJP. “His sentence ended over 20 years ago, and he had never known he could vote. It’s sad to learn that he could have been voting for the last 20 years, but I was glad that now he knows he can, and to hear how excited he was to register to vote.”

In Georgia, once a person completes their felony sentence and correctional supervision, their right to vote is automatically restored. But in the state with the highest rate of correctional supervision in the country, many Georgians remain unaware they can vote.

GJP has been working for years to help eradicate voter disenfranchisement of people who have been justice-involved. Executive Director Doug Ammar considers voting rights work vital to GJP’s holistic approach to social change, which is focused on legal representation and social services, policy advocacy and systemic change, and community outreach and engagement.

“Our two main goals are to reduce the number of people under correctional control and reduce barriers to reentry,” Ammar said. “Georgia has the highest rate of correctional control in the country and has for a long, long time, so we are really focused on trying to either keep people from going into the system or extracting them from the system.”

The Southern Poverty Law Center is helping to fund GJP’s voting rights work through the Vote Your Voice program with a grant of $400,000. The SPLC established the Vote Your Voice program in 2020 with $100 million in grants available to help grassroots organizations in the Deep South build capacity and extend their voter outreach and civic engagement efforts over the next decade.

Vote Your Voice Program Officer Robin Brulé said people who have been justice-involved face a troubling double standard as they are expected to reintegrate as productive members of their communities, while they are also being systematically stripped of rights and opportunities to do so.

“We expect justice-involved people to be good citizens and add value to our society, but then we take their rights away and create all these barriers to doing that,” Brulé said. “So beyond helping secure our democracy and the right to vote, the work of Georgia Justice Project is moral and ethical work that is essential to protecting human dignity.”

Here is a look at another Vote Your Voice grant recipient in Georgia and how it is using the funding:

Peach Concerned Citizens Inc. — Grant amount: $45,000

Founded in 2018, Peach Concerned Citizens Inc. (PCCI) is dedicated to educating voters about the importance of voting in all elections and promoting informed ballot casting. Serving Peach, Taylor, Crawford, Lee, Marion and Macon counties, the organization focuses on helping people understand what and whom they’re voting for and why. Through door-to-door canvassing, community events and innovative programs like free youth tennis camps paired with civic education for parents, PCCI educates voters about election processes, candidate platforms and issues facing their communities. PCCI’s mission emphasizes the importance of understanding policies and how elected officials at all levels — from president to local officials — impact voters’ daily lives.

Removing obstacles

Voting isn’t just a person’s right, Ammar said, it’s a critical part of community reintegration. GJP is working to demystify voting eligibility, provide clear information, train partner organizations and challenge systemic barriers to help thousands reclaim their civic voice.

A key to removing barriers to reentry for people who were formerly incarcerated and avoiding recidivism, Ammar said, is helping people become engaged in their communities.

“Of course, voting is an important way people can do that,” he said.

The barriers to voting are often layered and complex. With laws varying by state and widespread misinformation and disinformation about voting, Ammar said many people are left uncertain or misinformed about their rights.

Other obstacles stem from legacy systems and policies that make casting a ballot unnecessarily difficult. For years, Ammar said, people were turned away at local election offices when trying to register to vote after completing their sentences.

“The voting office would basically say, ‘Prove it. We don’t have anything here that says you completed your sentence,’” Ammar said. “The system didn’t generate anything to show that you had completed your sentence. For a while, we were just running around getting old probation officers to sign letters because we didn’t know what else to do.”

Eventually, GJP’s advocacy led Georgia’s Department of Community Supervision to provide certificates of sentence completion serving as official documentation proving an individual’s voting eligibility.

GJP also helps people who are on probation sentences that keep them from the ballot box.

“One in 25 Georgians is under correctional control, mainly because of felony probation,” Ammar said. “We have the largest number of people on felony probation of any state. Georgia has no limits on probation. A lot of our clients have 10, 20, 30, 40 or 50 years on probated sentences.”

In 2021, GJP helped pass a state law to allow the early termination of probation for people who have served three years, provided certain criteria are met. More than 20,000 Georgians have successfully terminated their probation early since the law passed.

GJP is also working to change state law to enable people on probation or parole to vote alongside the Georgia Rights Restoration Coalition, founded by the SPLC and Inner-City Muslim Action Network. A key tactic, said Colloton of GJP, is helping potential voters who have completed their sentences realize their power to influence policy.

“There are about 200,000 Georgians who cannot vote because they’re currently serving a sentence for a felony conviction, but there are also 450,000 Georgians who have a felony record but have completed their sentence who can vote and often don’t know it,” Colloton said.

“If we engage and empower these potential voters who can vote right now, they can have an influence on policy that could change the disenfranchisement situation,” she said. “Ideally, we would get rid of [voting restrictions] altogether, but the interim goal right now is to change the law so that people who are on supervision, which is the vast majority of people who are disenfranchised in Georgia, can vote.”

Ammar said understanding the racist roots of felony disenfranchisement laws is critical to confronting a system deliberately designed to suppress Black political power. The organization’s efforts to restore and expand voting rights directly challenge laws rooted in the racist aftermath of Reconstruction, when Georgia and other states scrambled to find new ways to disenfranchise people who had recently been freed from slavery. In the South, several states crafted disenfranchisement laws — focused on crimes they unjustly believed were most commonly committed by Black citizens — specifically designed to exclude Black men from voting.

“When you look at this history, you realize that these laws are not correlative to criminal justice but to racism and the end of slavery and the end of Reconstruction,” he said.

Ending ‘perpetual punishment’

Beyond voting, GJP hopes to end the perpetual punishment ingrained in the criminal legal system.

“It’s almost been accepted that we’re going to continue to punish people after they paid their due,” Ammar said. “When is enough enough?”

Ammar points to the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction. The database has cataloged more than 44,000 legal and regulatory restrictions that limit or prohibit people who have been justice-involved from accessing employment, business and occupational licensing, housing, voting and education, as well as other rights, benefits and opportunities.

“I think the heart of this is, when are we really letting people move past the past?” Ammar said. “When are we letting people really rejoin society? And when are we going to stop perpetual punishment?”

For more information about Georgia Justice Project, visit its website here. Learn more about the Vote Your Voice program and stories about grantees here.

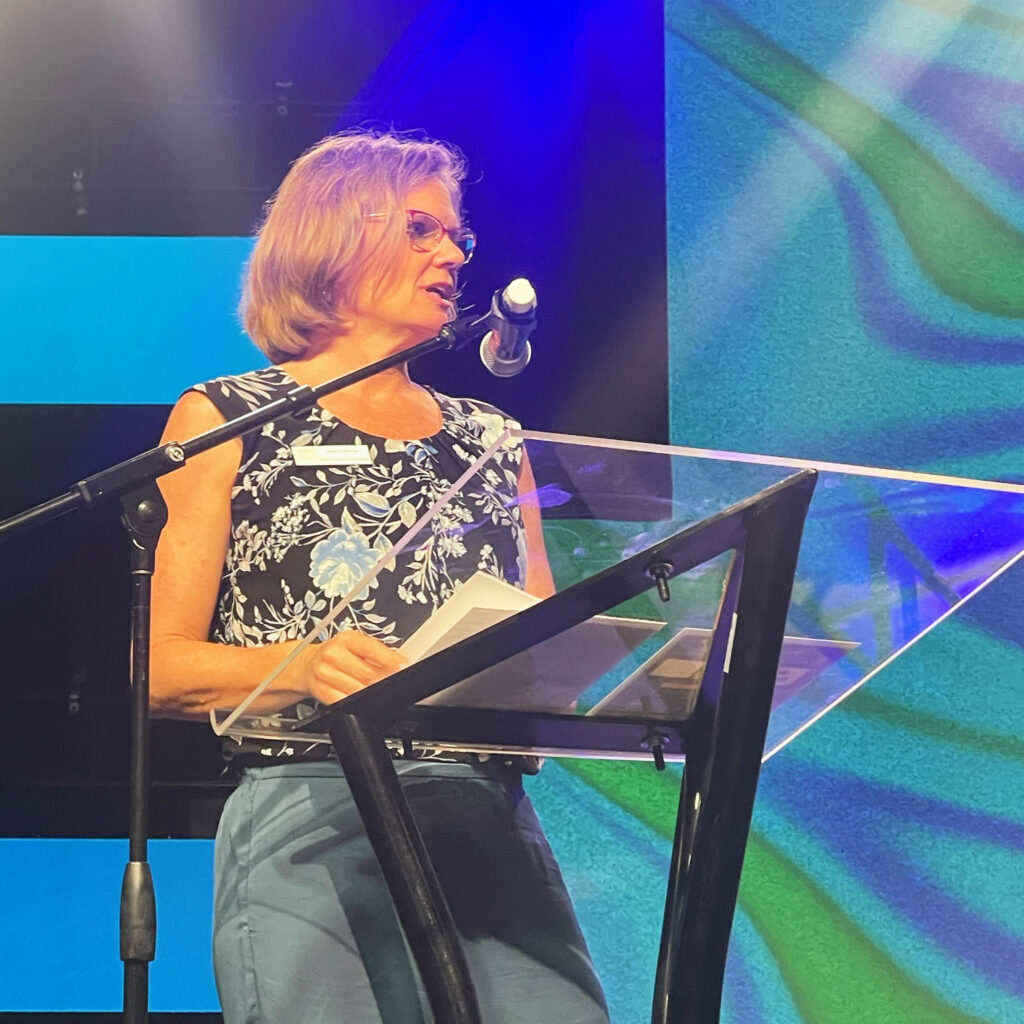

Image at top: Georgia Justice Project Executive Director Doug Ammar receives the Ben F. Johnson Public Service Award at Georgia State University on March 20, 2025. (Courtesy of Georgia Justice Project)