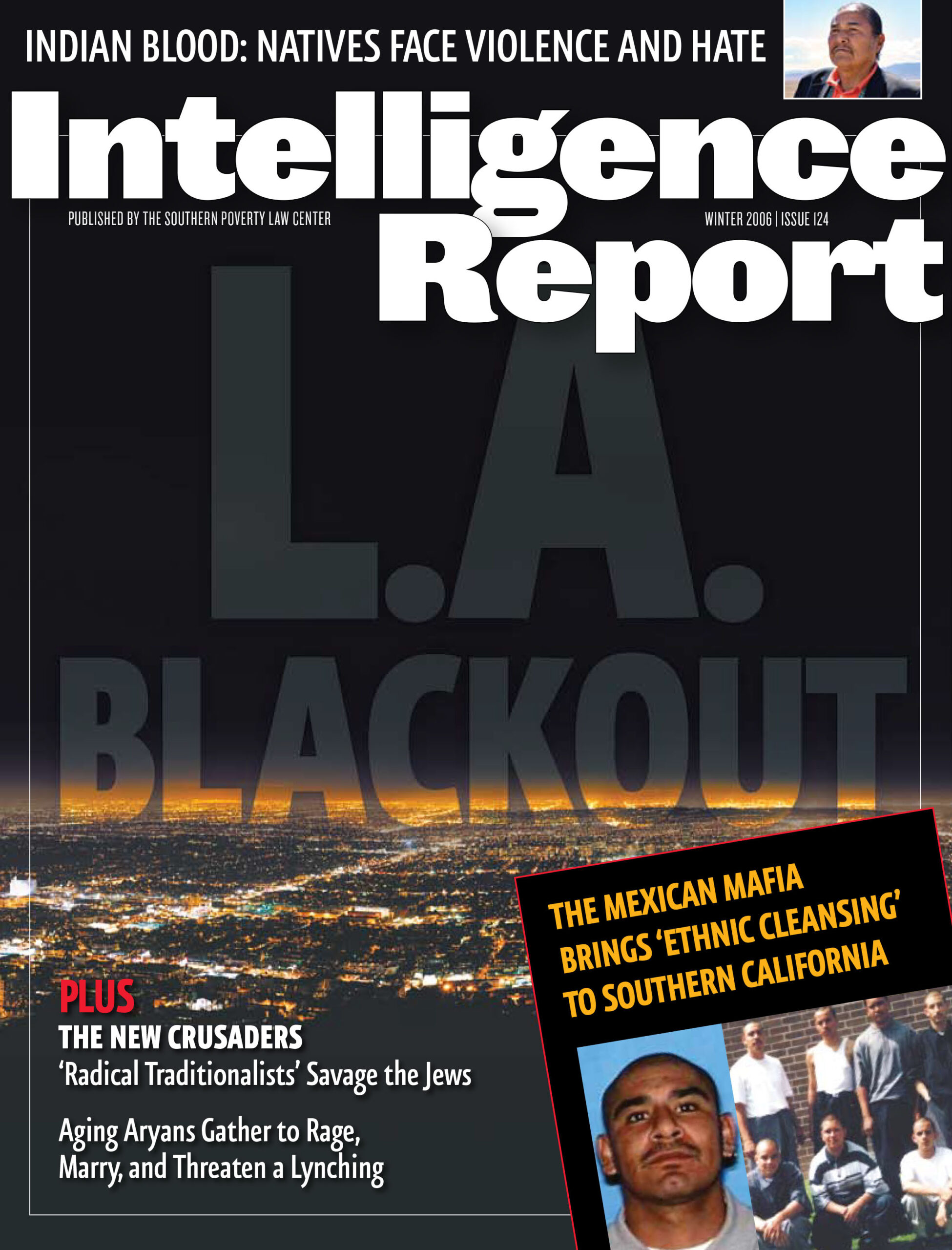

Acting on orders from the Mexican Mafia, Latino gang members in Southern California are terrorizing and killing blacks.

LOS ANGELES, Calif. — Ascending the steep steps that lead from the street to the scene of her son’s murder, 47-year-old Louisa Prudhomme is charged by a Doberman Pinscher.

Prudhomme reaches over a gate and gives the guard dog a rough pat on the head.

“Sam doesn’t seem to remember me,” she says.

What Prudhomme will never forget is that just past the snarling Doberman is the apartment on a hill where six years ago her 21-year-old son Anthony was shot in the face with a .25-caliber semi-automatic while lying on a futon she had purchased for him from IKEA. He died wearing a shirt that read, “Keep the Peace.”

Anthony Prudhomme was slain by members of the Avenues, a Latino street gang. But he was not a rival gang member, or a police informant, or a drug dealer. The Avenues did not target him for the content of his character, or even the contents of his apartment.

They targeted him for the color of his skin.

Prudhomme was murdered because he identified himself as black (he was in fact mixed-race) in a neighborhood occupied by one of the many Latino street gangs in Los Angeles County. Incredibly, even though these gangs are fundamentally criminal enterprises interested mainly in money, gang experts inside and outside the government say that they are now engaged in a campaign of “ethnic cleansing” — racial terror that is directed solely at African Americans.

“The way I hear these knuckleheads tell it, they don’t want their neighborhoods infested with blacks, as if it’s an infestation,” says respected Los Angeles gang expert Tony Rafael, who interviewed several Latino street gang leaders for an upcoming book on the Mexican Mafia, the dominant Latino gang in Southern California. “It’s pure racial animosity that manifests itself in a policy of a major criminal organization.”

“There’s absolutely no motive absent the color of their skin,” adds former Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorney Michael Camacho. Before he became a judge, in 2003, Camacho successfully prosecuted a Latino gang member for the random shootings of three black men in Pomona, Calif.

“They generally don’t like African Americans,” Pomona gang unit officer Marcus Perez testified in that case. “If an African American enters their neighborhood, they’re likely to be injured or killed.”

A comprehensive study of hate crimes in Los Angeles County released by the University of Hawaii in 2000 concluded that while the vast majority of hate crimes nationwide are not committed by members of organized groups, Los Angeles County is a different story. Researchers found that in areas with high concentrations, or “clusters,” of hate crimes, the perpetrators were typically members of Latino street gangs who were purposely targeting blacks.

Furthermore, the study found, “There is strong evidence of race-bias hate crimes among gangs in which the major motive is not the defense of territorial boundaries against other gangs, but hatred toward a group defined by racial identification, regardless of any gang-related territorial threat.”

Six years later, the racist terror campaign continues.

A Pervasive Attitude

Anthony Prudhomme presented no threat to the Avenues. Even so, he was murdered two months after he moved into Highland Park, a neighborhood in northeastern Los Angeles that is home to many gang members. “He didn’t have anything [to steal],” his mother says. “He had nothing when they broke in. So to shoot him, I’m sure it was a stripe. They get stripes for killing black people.”

“Stripes” are a gang-soldier’s badges of honor. Latino gang members in Southern California earn them by doing the bidding of their godfathers in the Mexican Mafia, a powerful criminal syndicate based in the California state prison system that controls most Latino street gangs south of Bakersfield.

According to gang experts and law enforcement agents, a longstanding race war between the Mexican Mafia and the Black Guerilla family, a rival African-American prison gang, has generated such intense racial hatred among Mexican Mafia leaders, or shot callers, that they have issued a “green light” on all blacks. A sort of gang-life fatwah, this amounts to a standing authorization for Latino gang members to prove their mettle by terrorizing or even murdering any blacks sighted in a neighborhood claimed by a gang loyal to the Mexican Mafia.

“This attitude is pretty pervasive throughout all the [Latino] gangs,” says Tim Brown, a Los Angeles County probation supervisor. “As long as [street] gangs are heavily influenced by the prison gangs, particularly the Mexican Mafia, racism is just part and parcel of why they come into being and why they continue to exist.”

Last fall, four members of the Avenues were convicted of federal charges for conspiring to deprive blacks of their civil rights in Highland Park. Three of them were sentenced to life in prison, without the possibility of parole, in late November; a fourth was to be sentenced the following month.

But the problem is far more widespread than a single gang in a single neighborhood.

Random, racially motivated crimes have been committed across the 88 cities of Los Angeles County by the members of Latino gangs, including the Pomona 12 in the city of Pomona, the 18th Street Gang in southwest Los Angeles, the Toonerville gang in northeast L.A., and the Varrio Tortilla Flats in Compton.

In one typical case, three members of the Pomona 12 attacked an African-American teenager, Kareem Williams, in his front yard in 2002. When his uncle, Roy Williams, ran to help his nephew, gang member Richard Diaz told him, “N—— have no business living in Pomona because this is 12th Street territory.” According to witnesses, Diaz then told the other gang members, “Pull out the gun! Shoot the n——! Shoot the n——!” No shots were fired.

The violence is not even limited to Los Angeles County. This November, six members of a Latino gang in Carlsbad, Calif., were arrested and charged with hate crimes for allegedly hurling racial slurs at a black teenager — who police said was not a gang member — while kicking and punching him. The same month, two members of the Fresno Bulldogs, a Latino gang in Fresno, Calif., were convicted of attempted murder in what police described as the random hate-crime shooting of a 41-year-old black man. According to police, the shooters used racial epithets and told the victim, “We don’t like your kind of people on our street.”

Ten Years of Terror

Anti-black violence conducted by Latino gangs in Los Angeles has been ongoing for more than a decade. A 1995 Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) report about Latino gang activity in the Normandale Park neighborhood declared, “This gang has been involved in an ongoing program to eradicate Black citizens from the gang neighborhood.” A 1996 LAPD report on gangs in east Los Angeles stated, “Local gangs will attack any Black person that comes into the city.”

But while the Latino gangs’ racial terror campaign is not new, gang experts and law enforcement authorities say the intensity and frequency of anti-black terrorism is now escalating, as the amount of turf in Los Angeles claimed by Latino gangs continues to increase rapidly. And, as more and more blacks leave inner-city L.A. for safer neighborhoods, those who remain are more vulnerable.

“I don’t see much history left for blacks in Los Angeles,” says LAPD probation officer James Lewis, who is himself black and deals specifically with Latino gang members in northeast Los Angeles, including the Avenues. “It plays out not just with the gang members, but also the way things are going [for blacks] throughout Los Angeles.”

Since 1990, the African-American population of Los Angeles has dropped by half as blacks relocated to suburbs, and Latinos have moved into historically black neighborhoods. Traversing South Central L.A. today, it’s obvious that the urban landscape has changed radically since the Bloods-versus-Crips era depicted in movies like Colors, Boyz N The Hood, and Menace II Society. Not only are there vastly fewer black people walking the streets, there are vastly fewer obvious black gang members. Beige skin and baggy khakis have displaced the red and blue bandanas of the Bloods and the Crips.

The LAPD estimates there are now 22,000 Latino gang members in the city of Los Angeles alone. That’s not only more than all the Crips and the Bloods; it’s more than all black, Asian, and white gang members combined. Almost all of those Latino gang members in L.A. — let alone those in other California cities — are loyal to the Mexican Mafia. Most have been thoroughly indoctrinated with the Mexican Mafia’s violent racism during stints in prison, where most gangs are racially based.

“When I first started working the gangs, they would be mixed. You could be black and Latino and be in the same gang,” says Lewis, the LAPD probation officer. “But when they went to prison, they had to be Latino instead of from the gang, so their enemies became African Americans.”

A Landmark Case

In Highland Park, located just north of downtown and one of oldest settled areas in Los Angeles, there have been at least three racially motivated “green light” murders committed by members of the Avenues since 1999.

Besides Anthony Prudhomme, the victims included Christopher Bowser, a black man who was bullied and sporadically assaulted for years by Avenues members, then gunned down in broad daylight at a bus stop, and Kenneth Kurry Wilson, who didn’t even live in the vicinity. Wilson was simply parking his car to drop off his nephew after a late night at a bar when he crossed paths with Avenues gang members riding in a stolen van. According to later court testimony, one of the gang members in the van spotted Wilson and said, “Hey, wanna kill a n—–?” The group opened fire on Wilson, killing him instantly.

The murders of Bowser and Wilson resulted in a groundbreaking criminal case brought by the U.S. Department of Justice, in which Alejandro “Bird” Martínez, Fernando “Sneaky” Cázares, Gilbert “Lucky” Saldana, and Porfirio “Dreamer” Avila were convicted last August of violating federal hate crime laws, and later sentenced to life in federal prison. (Avila was already serving life in prison after being prosecuted by the state of California for his role in the killings, while Saldana was incarcerated for his role in another murder). In the past, federal prosecutors have typically used civil rights violation conspiracy laws against members of white supremacist groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan. The federal case against the Avenues gang marked the first time the Department of Justice used such laws against members of a non-white criminal organization, officials said.

“In a diverse community such as Los Angeles, no one should face race-based threats and acts of violence, such as those committed by [the Avenues],” U.S. Attorney Debra Wong Yang said in a statement released after the verdicts were rendered.

The victims, Yang added, “were killed by the defendants simply because they were African Americans who chose to live in a particular neighborhood.” During the trial, federal prosecutors also detailed a series of less-than-lethal hate crimes committed by Avenues members in recent years to establish a pattern of violent racial harassment.

The evidence showed that Avenues members pistol-whipped a black jogger in Highland Park; used a metal club to beat a black man who had stopped to make a call at a pay phone; shot a 15-year-old black youth riding a bicycle; and drew outlines of human bodies in chalk in the driveway of a black family that had moved into the neighborhood.

Prosecutors brought the federal hate-crimes case against the Avenues to send all Latino gangs in Los Angeles County a message that ethnic cleansing will not be tolerated. (Federal prison time is a greater threat to gang leaders than California state prison time, both because there is no parole in the federal system and because the federal government routinely transfers gang leaders to penitentiaries far from home, where they are cut off from the support and protection of their gang.)

“We were concerned about the violation of people’s civil rights,” U.S. Attorney’s Office spokesman Thom Mrozek told the Intelligence Report. “Being shot at a bus stop just for being black, obviously that should not be taking place.”

The government’s message may have been received, but it’s not being obeyed. Shortly after the federal hate crimes trial ended this fall, Avenues member James “Drifter” Campbell, 47, was charged with criminal threats for pointing a gun at a 17-year-old African-American high school student in Highland Park, the second such incident that month.

Mrozek said there are currently no plans to bring more federal hate crimes charges against other Latino gang members, though he acknowledges that similar crimes “are probably still going on.”

Lawless Avenues

Despite all the highly publicized gang activity, Highland Park is no ghetto. It’s a hilly area with beautiful, historic homes, where the painted-lady color schemes on fully restored Queen Anne Victorians compete for attention with the vibrant murals found on nearby food markets. “El Alisal,” the famed hand-built, stone home of Charles Lummis, the first city editor of the Los Angeles Times, is tucked just off the Pasadena Freeway, on Avenue 43.

Because Avenue 43 is one of the main roads in Highland Park, “43” is the signifier of the Avenues, also known as “Avenues 43.” The gang goes back at least to World War II, when Highland Park was populated with a mixture of European and Latino immigrants. Now, about 75% of Highland Park residents are Latinos. Only 2% are black. The rest are white and Asian.

Highland Park has long had a reputation for gang problems that community boosters argue is undeserved. Their cause wasn’t helped in 1986, when one of Highland Park’s most famous residents, songwriter Jackson Browne, released the song, “Lawless Avenues,” about the neighborhood’s multi-generational gang: “Fathers’ and sons’ lives repeat/And something there turns them/Down those lawless avenues.”

Although the Avenues gang goes back a half century, it only fell heavily under the control of the Mexican Mafia in the 1980s, eventually becoming fundamentally racist as a result. (Police point out that, ironically, the Avenues now sling dope for the Mexican Mafia, which the gang’s leaders in decades past looked down upon as a “black thing.”)

Still, at least some of the relatively few black Highland Park residents who’ve lived in the area for more than a decade don’t report the same level of fear as others. “We love our neighbors. We love living in Highland Park,” says Vernita Strange, who moved to Highland Park with her husband Al in the mid-1970s. “We’ve been treated warmly. We’ve been here 30 years, and that’s all I have to say.”

But Angel Brown, an African American, didn’t experience that same kind of neighborly love when she and her teenaged son Christopher Bowser moved to Highland Park in 1998, in large part to get away from the black gangs in the Hoover Street area where he grew up. There, he caught a bullet in the leg in a drive-by and was beaten up and harassed by the Hoover Crips, who pressured him to join their set. “He knew early on that [gangbanging] was something he did not want to do,” says Brown.

The pair was hoping to leave gang trouble behind, but soon after they relocated to Highland Park the Avenues targeted Bowser. “My son had problems because he’s a young black man. The Avenues up there called him ‘n—–‘ and stuff and chased him,” Brown says. “He didn’t bother nobody out there, all he did was walk around with his radio, singing and rapping. They didn’t want him in their territory.”

Testifying in the federal hate crimes trial against his former gang brethren, ex-Avenues member Jesse Diaz confirmed the Latino gangbangers were infuriated by the way Bowser bopped down the street, blasting rap music on his boom box.

He acted, Diaz testified, “like it was his neighborhood.”

Murderous Prejudice

Until Anthony Prudhomme’s murderers went on trial, it never dawned on his mother, Louisa, and his stepfather Lavalle, that the killing was racially motivated. “It wasn’t until we went to the trial that we really began to understand that [race] was the reason,” he says, “which seemed totally, for lack of a better word, stupid.”

Since the trial, Louisa has become obsessed with the Avenues gang. She routinely drives Highland Park, looking for signs of the gang, talking to anyone willing to talk. She has homicide detectives, lawyers, and parole officers on her cell phone’s speed dial. She’s made numerous visits to the site of her son’s murder, as well as the spots where Bowser and Wilson were shot down. Believing the gang member who actually pulled the trigger on her son has yet to be brought to justice, she posts reward signs throughout the neighborhood, usually right next to Avenues gang graffiti.

Unlike the mothers of other victims like Bowser and Wilson, Louisa Prudhomme feels relatively safe on streets claimed by the Avenues. That’s because she’s white. Her son Anthony had long, wavy hair and an auburn complexion. “As he grew up people thought that” he might have been some race other than black, says his stepfather Lavelle. “But you could tell by the way he dressed that he leaned more toward his African-American side.”

That preference may well have cost him his life, something that infuriates his mother. “A friend of mine asked me do I hate Mexicans now,” says Louisa. “I said, ‘I hate murderers.’ I am prejudiced … against murderers.”

Driving through Highland Park one afternoon last October, Louisa headed up Avenue 43 toward Montecito Heights Community Center, a known Avenues congregation spot. She pulled up alongside a man loading lawnmowers into a huge shed. The man grabbed the left door, which was decorated with a full-length, spray-painted “4,” and joined it with the right door, which was tagged with a matching “3.” When the doors were closed, they created the “43” emblem of the Avenues.

Louisa asked the man, who was Latino, if he spoke English. He did, and they chatted for about five minutes about the infamous “Avenues 43” and the tattoos they leave all over the area he landscapes. Louisa walked away from him, laughing, before turning to say, “I hope they get them all. We want to get all of them off the streets.”

But with the Mexican Mafia’s shadow looming over Los Angeles, it may be a long time before the rapidly growing number of streets claimed by Latino gangs are safe for blacks, if ever.

“It’s not just Highland Park. It’s almost anywhere in L.A. that you could find yourself in a difficult position [as a black person],” says Lewis, the LAPD probation officer. “All blacks are on green light no matter where.”