Neo-Confederacy is a reactionary, revisionist branch of American white nationalism typified by its predilection for symbols of the Confederate States of America, typically paired with a strong belief in the validity of the failed doctrines of nullification and secession — in the specific context of the antebellum South — that rose to prominence in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Top Takeaways

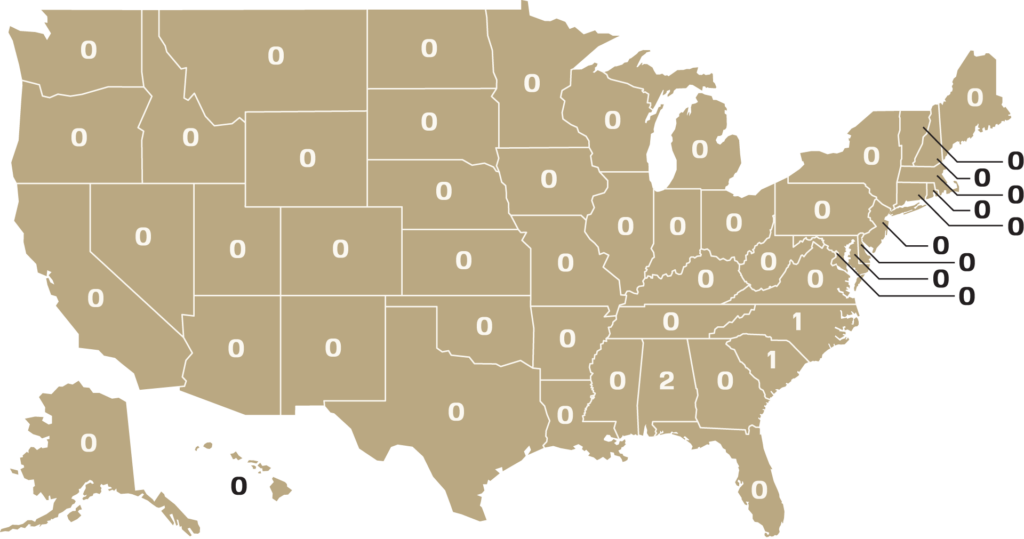

SPLC analysts documented 14 neo-Confederate hate groups in 2022, with a drop to five groups occurring in 2023. In 2024, the neo-Confederate category continues to struggle and now comprises a mere four groups.

Much of this decline is due to the decreasing relevance and reach of the League of the South (LoS). Long the central organization within this branch of white nationalism, the League of the South has not rebounded from fallout from its attendance at the deadly riot in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017. This has continued to impede the group’s recruiting. While 10 chapters persisted in 2022, by 2024 only two remained operational.

Neo-Confederate group Identity Dixie has also faltered, still reeling from revelations about the group’s leaders that the SPLC exposed in 2019. Today, Identity Dixie is down to one chapter.

Neo-Confederate hate groups continue to face financial challenges following a civil lawsuit brought against group leaders by Integrity First for America after the 2017 Charlottesville rally. Still, a dedicated and loyal following of neo-Confederate extremists continue to plot online and use efforts to remove Confederate monuments; rename parks, schools and other public spaces to rally other extremists to their ideology; and recruit new members and fundraise from the larger radical-right movement.

Key Moments

As the neo-Confederate movement struggled for relevance in 2024, the once formidable League of the South was unable to organize its annual conference, marking a harsh nadir for a group that only a decade ago claimed thousands of members across the South. Facing costly financial obligations awarded to plaintiffs in the long-running Sines v. Kessler civil case against the organizers of the deadly 2017 “Unite the Right” rally, including two leaders of the League, Michael Hill and Michael Tubbs, the group restructured the organization to provide more authority to chapter leaders. These moves have led to infighting as chapter leaders started to exert discretion over the group’s finances.

In November 2024, Michael Hill rebranded LoS as the Southern Nationalist League. Complete with a new website, podcast and blog, the new venture seemingly provides LoS an opportunity to avoid the financial burden stemming from the Sines v. Kessler case. The Southern Nationalist League’s website includes an online shop, a donation page and provides information on how to become a dues-paying member. The rebranded group sells the LoS flag as well as apparel with LoS symbols.

As the League of the South rebrands, coordination between neo-Confederate groups continues. In July 2024, the Dixie Republic hosted Dixie Fest, which featured talks from leaders of the League of the South as well as Identity Dixie. In August 2024, The Southern Cultural Center hosted its third annual conference, which featured John Weaver, an extremist who was a leader in the Council of Conservative Citizens; white nationalist Jared Taylor, who leads American Renaissance; and white nationalist radio host James Edwards. In November, members of the Southern Cultural Center traveled to Tennessee to attend the American Renaissance conference, which included lectures by former Klan lawyer Sam Dickson, white nationalist propagandist Kevin DeAnna and University of Pennsylvania Law School professor Amy Wax.

What’s Ahead

In recent years, ongoing debates around public memorials to the Lost Cause galvanized small groups that have promoted neo-Confederate ideology and spawned pro-monument groups relatively new to the neo-Confederate hate movement. Energized online and among its ranks, the movement has nonetheless failed to organize and mobilize widely across the South. The New York Times reported that by July 3, 2020, 15 million to 26 million people attended protests across the U.S. against the killing of George Floyd. But while neo-Confederates failed to gain a noticeable uptick in recruits across 2024, continued conflict over Lost Cause memorials and public institutions named for Confederate military officers may provide opportunities for neo-Confederates to engage in violence during 2025. Weighed down by the financial burden following the conclusion of the Sines v. Kessler civil case, the League of the South may attempt to reassert itself again through public rallies as well as use misinformation about global conflicts, gender-affirming care, so-called critical race theory or other conservative moral flashpoints to stay relevant in the radical right.

Background

Neo-Confederacy also incorporates advocacy of traditional gender roles, is hostile toward democracy, strongly opposes homosexuality and exhibits an understanding of race that favors segregation and promotes white supremacy.

An overall conservative ideology, neo-Confederacy has made inroads into the Republican Party from the political right and overlaps with the views of white nationalists and other, more radical extremist groups. Today, some prominent neo-Confederates are joining the larger push by conservative politicians and radical-right groups to stoke fear about COVID-19 vaccines, mask mandates and events that feature LGBTQ+ inclusion.

Adding antisemitic and racist messaging to conspiracies about vaccines, sexual orientation and gender, neo-Confederates are asking their supporters to harass and intimidate local, state and federal health officials, hospital staffs and business owners. Movement leaders are also calling on their supporters to intimidate school board officials, teachers and teachers’ unions for their support of vaccines and inclusive education.

In this regard, neo-Confederacy is best viewed as a spectrum, an umbrella term with roots dating back as early as the 1890s. It applies to groups including the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) of the 1920s and others resisting racial integration in the 1950s and 1960s. In its most recent iteration, neo-Confederacy is used by both proponents and critics to describe a belief system that has emerged since the early 1980s in such publications as Southern Partisan, Chronicles and Southern Mercury and in organizations including the League of the South (LOS), the Council of Conservative Citizens and the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

The Spectrum Explained

In relation to far-right American hate groups, the term “neo-Confederate” refers to a specific subset of American white nationalism predominant in the Southeastern U.S. that fuses the typically strong, nativist immigration policies, Christian dominionism, Confederate “heritage and pride” and other supposedly fundamental values of the “heritage crowd” with a belief in the inherent superiority of white people of European descent.

Neo-Confederacy represented a much more unified front in the late 20th century, when there was a great degree of cross-membership between such groups as the League of the South, Abbeville Institute, Ludwig von Mises Institute and American Renaissance, among others.

A concerted effort was made by many of these groups’ leaders to cast off the old conception of white supremacy so often tied to the image of the Ku Klux Klan — at that point (and to this day) a constellation of groups with shared symbols and structure often viewed as thoroughly compromised by federal informants — and adopt a more academic veneer.

While this strategy had some successes, its novelty and efficacy soon faded as older leaders died and groups either failed to pull in new recruits or slid rightward into the hate movement, as in the case of the League of the South.

When describing neo-Confederate hate groups, there are two notable entities with any clear level of leadership and organization: the League of the South and Identity Dixie, the latter an offshoot of the white nationalist blog and podcasting site The Right Stuff (TRS), which has grown since its formation in 2017 due to substantial overlap with LoS.

In the shared conception of LoS and Identity Dixie, an independent South would stand for the rejection of a standing army in favor of unregulated state militias, the right of citizens to own any firearms they may purchase, the right of states to secede from the new Confederate States of America (CSA), closed borders and restrictions on the rights of “noncitizens.”

Both groups would tend toward a description of “the Southern people” that was given by League President Michael Hill in 2004:

“In 2004, I began to publicly speak on the fundamental notion of Southern nationalism. That is, I began identifying the Southern nation correctly as the Southern people (whites) and not as a current or defunct political entity. … We stand for the Anglo-Celtic people of the South and that we defend our historic Christian faith.”

Hatewatch does not list “heritage,” paleo-libertarian or “constitutional” groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), UDC, Ludwig von Mises Institute, the Rockford Institute, Virginia Flaggers or South Carolina Secessionist Party as hate groups, though they have strong neo-Confederate principles and choose to spend their time and money valorizing the negative parts of U.S. history. Yet in their effort to gloss over the brutal legacy of slavery in the South, these groups strengthen the appeal of Lost Cause mythology, opening the door for violent incidents spurred by the rhetoric of cynical individuals and groups like the League and Identity Dixie.

Lost Cause

The term “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” refers to a collection of political and historical myths that form the bedrock of many notable neo-Confederate slogans. “Heritage not hate” and “states’ rights” have shared roots in the post-Reconstruction effort to revise the indisputable fact of why the South seceded from the Union in the 1860s: slavery.

While most Lost Cause exponents would balk at brazen racism, a recent study by the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance (now Learning for Justice) in partnership with Survey USA shows that milder forms of the mythology have permeated the American education system to an alarming degree.

In a survey of high school seniors, only 8% surveyed could identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War. Two-thirds (68%) did not know that it took a constitutional amendment to formally end slavery, and fewer than 1 in 4 students (22%) could correctly identify how Constitution provisions privileged slaveholders.

Among the study’s recommendations was the suggestion that teachers and schools remedy this deficit of understanding by teaching about the Civil War and American slavery through use of original historical documents.

Using this approach, the Lost Cause myth of the “states’ rights” justification for secession popular among neo-Confederates falls flat when viewed in the context of primary-source historical documents.

Five of 11 states that seceded during the Civil War explicitly mentioned slavery in their ordinances of secession. From the Alabama ordinance of secession:

Be it further declared and ordained by the people of the State of Alabama in Convention assembled, that all powers over the Territory of said State, and over the people thereof, heretofore delegated to the Government of the United States of America, be and they are hereby withdrawn from said Government, and are hereby resumed and vested in the people of the State of Alabama. And as it is the desire and purpose of the people of Alabama to meet the slaveholding States of the South, who may approve such purpose, in order to frame a provisional as well as permanent Government upon the principles of the Constitution of the United States.

In each of the other six states, prominent elected representatives spoke of slavery’s integral nature to their economy and body politic. From Louisiana’s then-Gov. Thomas Moore:

I do not think it comports with the honor and self-respect of Louisiana, as a slaveholding State, to live under the Government of a Black Republican President.

“Lost Cause” proponents have developed a long list of excuses and explanations for these statements that clearly advocate for the continuation and advocacy of slavery.

Some groups, such as the League of the South, recognize that denying the outright bigotry of the antebellum South is an ineffective bargaining strategy when advocating for the preservation of Confederate monuments. The League has become quite brazen on the question of slavery.

In a Facebook post on the League’s group page, Hill stated:

If you think you have to apologize for or rationalize slavery, “racism,” segregation or any other actions our attitudes of our Southern forebears, then you don’t belong in The League of the South.

Flags, monuments and other symbols

The Charleston Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church shooting in South Carolina reignited a long-running debate over the meaning and prominence of neo-Confederate iconography in the public square after photographs posted online showed the shooter brandishing the Confederate battle flag and other neo-Confederate iconography. Neo-Confederates can hardly be described as a unified front, although almost all advocate for the continued display of the Confederate battle flag (CBF) and statuary devoted to Confederate generals like Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson at courthouses and in squares across the United States.

The history of the numerous flags of the Confederacy is emblematic of the ways in which neo-Confederates often take a piecemeal approach in their doomed attempts to construct a cogent ideology that is unassailable from the facts of history.

One of the most easily recognizable symbols of neo-Confederacy is the Confederate battle flag (CBF). Neo-Confederates venerate the CBF and almost universally believe that it should remain a prominent public symbol.

The flag’s designer, William Porcher Miles, had originally proposed a similar flag at South Carolina’s 1860 secession convention, featuring a blue St. George’s Cross and his home state’s iconic palmetto and crescent. At the request of a Jewish Southerner, Miles abandoned the upright St. George’s Cross so that “a symbol of a particular religion not be made the symbol of the nation,” replacing it with a diagonal St. Andrew’s Cross. The palmetto and crescent were replaced with a star for each Confederate state in secession from the Union.

Despite its well-documented provenance, a popular claim among neo-Confederates is that the Confederate battle flag has overt religious connotations.

The CBF was never the official flag of the Confederate States of America (CSA). After it gained popularity due to its adoption as the flag of the Army of Northern Virginia, variations of the flag were used during the war as components of the CSA’s national flag and as the Second Confederate Jack and Ensign.

The CSA had three official flags during its short existence. The “First National” was abandoned due to its design mimicking the American flag too closely. While the CBF is often erroneously referred to as the “Stars and Bars,” that nickname actually belongs to the First National.

The second flag of the CSA, the “Stainless Banner,” was designed with the “Southern Cross” canton in the upper left corner. The Southern Cross was the flag of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, the iconic Confederate battle flag. The “Second National” was abandoned for too closely resembling a white flag of surrender in windless conditions.

The third, the “Blood-Stained Banner,” is nearly identical to the Stainless Banner with the addition of a red stripe on the right edge.

Various unofficial flags of the Confederacy proliferate at neo-Confederate “heritage” rallies. Two of the most iconic flags of the Confederacy stem from Spanish rule of Florida and the Republic of West Florida, as parts of what became Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama were known at the time. The “Bonnie Blue flag” was the official flag of the Republic of West Florida. It features a blue field with a single white star and flew above the Charleston batteries that opened the Civil War with the shelling of Fort Sumter.

The Spanish Cross of Burgundy, which features a white field with two stylized red tree branches crossing to form a saltire (X), draws on the familiar St. Andrew’s Cross. The legacy of Spain’s colonial incursion into North America lives on in the flags of Florida and Alabama, both of which feature a simplified red saltire. These flags were adopted as salutations to the Confederacy and the rebel battle flag during the rise of Jim Crow in the late 1800s.

Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi and Arkansas all have flags that contain references to the Confederacy, ranging from oblique mimicry of one of the three CSA national flags to overt incorporation of the CBF.

Mississippi has been embroiled in several public disputes and legal battles over its continued inclusion of the CBF in the canton of its state flag. The banner has been so divisive that the architect of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., removed it from public display in a tunnel that features flags from all 50 states. In 2021, after more than a century of including the CBF in its state flag, the CBF was removed. Following the murder of George Floyd, political leaders in Mississippi responded to calls to change the flag by creating a commission to find a new design and then held a referendum on the new design in November 2020. The referendum passed 72.98% to 27.02%, and a new state flag without the CBF was introduced in January 2021.

Various other unit or regimental flags particular to specific bands of fighters might often appear at rallies. Widely known examples include the Army of the Trans-Mississippi flag, which is a color-inverted CBF, and the Kentucky Orphan Brigade flag, which features a star-studded red crucifix centered on a blue field.

More recently, many neo-Confederate hate groups have adopted a new banner developed by Michael Cushman, former South Carolina state chairman for the League of the South.

In creating his flag, Cushman drew on the St. Andrew’s Cross, which is featured in the CBF and various state flags designed to mimic it. His bare-bones iteration consists of a black saltire emblazoned on a white banner. The Cushman flag first began to appear publicly in 2013, adorning the shirts, signs and trucks of LoS members at rallies across the Southeast.

In 2013, LoS President Michael Hill wrote:

[W]e now have adopted a Southern nationalist flag — a black St. Andrews cross on a white field — that is The League’s own banner. It is not intended to replace any of our historic Southern/Confederate flags; it is merely our own contribution. It is a symbol that belongs uniquely to us as a Southern nationalist organization.

Cushman has since become involved with Identity Dixie and has promoted his CBF adaptation, though bearing a cartoon magnolia — the symbol of Identity Dixie — at its center.

As public calls for the removal of the CBF and other Confederate memorials have increased, the deep-seated appeal of neo-Confederate symbols and their underpinning ideological worldview have come into stark relief.

The development of the Cushman flag occurred during a short-lived period in which the League publicly attempted to distance itself from the CBF. At the time, Brad Griffin, a League of the South member who writes under the pseudonym “Hunter Wallace” on his white nationalist blog “Occidental Dissent,” described the flag as “a ‘redneck pride’ symbol … worn on tacky bikinis by tasteless women.”

Almost overnight, after the June 17, 2015, massacre of nine Black parishioners in Cushman’s home state of South Carolina, the League positioned itself as the primary defender of the flag, as calls grew nationally for its removal as a symbol in the public square.

Cross-Ideological Appeal

In May 2017, members of the League of the South joined a group of far-right activists at New Orleans’ Lee Circle to protest the city’s removal of Confederate monuments. The group had come looking for a fight. Although they were largely disappointed on that front, the cross-movement appeal of Lee’s image — as evidenced by a wide array of flags ranging from the Confederate battle flag, Klan logos, Civil War kepis, Norse runes, the flag of “Kekistan,” the Gadsden flag and U.S. flags — as a catalyst for violent mass protest by the right would portend events to come.

Efforts by the Charlottesville (Virginia) City Council to remove a monument in one of its largest parks dedicated to Robert E. Lee spurred white nationalist blogger Jason Kessler to agitate for the removal of the council’s only Black member, Wes Bellamy. Although Kessler was a virtual unknown at the time, he managed to latch onto the appeal of the monument to other white nationalists.

“Alt-right” spokesperson Richard Spencer hosted an impromptu rally at the monument on May 13, 2017, not long after the Lee Circle event in New Orleans. Attendees hoisted tiki torches and decried efforts to remove the statue as indicative of a larger conspiracy to replace descendants of white Europeans in the U.S.

The event had a relatively small turnout. News coverage centered on the clear visual similarity between the event and a Ku Klux Klan rally. Kessler, feigning outrage at the “hyperbolic demonization and fearmongering about white people,” began organizing what would eventually become the Unite the Right rally.

The appeal of Confederate monuments to groups like national socialists and the patriot community — all of which have clearly different political objectives and beliefs from antebellum Southerners — can be hard to grasp. When that appeal is viewed within the context of reactionary white supremacy, a much more cogent school of thought emerges.

The otherwise anachronistic devotion to Confederate monuments and symbols prevalent on the far right was best summarized by Cody Wilson, the creator of the 3D-printed pistol and the alt-crowdfunding site Hatreon. On an episode of the far-right blog Red Ice Radio’s “Radio 3Fourteen” with host Lana Lokteff, Wilson had this to say regarding Confederate monuments:

“We do have to recognize that the Lost Cause narrative did win in the South. I’m speaking from Austin, Texas. If you go to the Capitol, there’s a monument to the Confederate States of America there and monuments to Robert E. Lee. … Down here the Lost Cause narrative won. But there’s this recriminative view of history that all narratives that are not consistent with modernity, the narrative of progress — both ethical and material popular progress — all narratives that don’t align with that narrative must be whitewashed. It’s not just enough to say that it’s untrue, the Lost Cause narrative of the South. It’s important to eradicate its symbolic heritage and its thought because it’s a threat to the progress of history. And so when I see the elimination of a symbol, right the elimination — I’m not just sympathizing with Southern white racists — I’m basically recognizing a dangerous mode of post-politics: the need to eradicate a historical narrative. Not just the need to combat it, the need to make sure that its symbols are gone, the way to articulate it is gone.”

Wilson’s take is a sober recognition that the animus driving recalcitrant opposition to the removal of Confederate memorials represents a once-widespread, virulent ideology fighting for its survival.

The bloody excesses on display at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, were not the first — nor will they be the last — incident of violence related to the unraveling of the Lost Cause narrative. As the appeal of neo-Confederate ideology and symbols wanes among the general American public, it is becoming much more deeply entrenched among all stripes of the far right. It will be necessary for those who oppose it to recognize its various forms and presentations and how it interacts with and affirms seemingly incongruous political ideologies, often to devastating effect.

2024 Neo-Confederate Groups

* – Asterisk denotes headquarters.

Dixie Republic

Travelers Rest, South Carolina

Identity Dixie

North Carolina

League of the South

Alabama*

Southern Cultural Center

Wetumpka, Alabama