The Al Qaeda English-language magazine "Inspire" is a key online breeding ground for Islamic terrorists. The equivalent for radical racists is Stormfront, the largest white supremacist Web forum in the world. A two-year investigation by the Intelligence Report finds that in the five years since Barack Obama was elected as our first black president, registered members of Stormfront have murdered close to 100 people.

A typical murderer drawn to the racist forum Stormfront.org is a frustrated, unemployed, white adult male living with his mother or an estranged spouse or girlfriend. She is the sole provider in the household. Forensic psychologists call him a “wound collector.” Instead of building his resume, seeking employment or further education, he projects his grievances on society and searches the Internet for an excuse or an explanation unrelated to his behavior or the choices he has made in life.

His escalation follows a predictable trajectory. From right-wing antigovernment websites and conspiracy hatcheries, he migrates to militant hate sites that blame society’s ills on ethnicity and shifting demographics. He soon learns his race is endangered — a target of “white genocide.” After reading and lurking for a while, he needs to talk to someone about it, signing up as a registered user on a racist forum where he commiserates in an echo chamber of angry fellow failures where Jews, gays, minorities and multiculturalism are blamed for everything.

Assured of the supremacy of his race and frustrated by the inferiority of his achievements, he binges online for hours every day, self-medicating, slowly sipping a cocktail of rage. He gradually gains acceptance in this online birthing den of self-described “lone wolves,” but he gets no relief, no practical remedies, no suggestions to improve his circumstances. He just gets angrier.

And then he gets a gun.

There is safety in the anonymity of the Web, and comfort in the endorsement others offer for extreme racist ideas, argues former FBI agent Joe Navarro, who coined the term “wound collector.” “Isolation permits the free expression of ideas, especially those which are extreme and which foster passionate hatred,” Navarro, who helped found the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Division, wrote in 2011 in Psychology Today. “In this cocoon of isolation the terrorist can indulge his ideology” without the restrictions of the routines of daily life.

Then there is a trajectory from idea to action.

Though on any given day, fewer than 1,800 registered members log on to Stormfront, and less than half of the site’s visitors even reside in the United States, a two-year study by the Intelligence Report shows that registered Stormfront users have been disproportionately responsible for some of the most lethal hate crimes and mass killings since the site was put up in 1995. In the past five years alone, Stormfront members have murdered close to 100 people. The Report’s research shows that Stormfront’s bias-related murder rate began to accelerate rapidly in early 2009, after Barack Obama became the nation’s first black president.

For domestic Islamic terrorists, the breeding ground for violence is often the Al Qaeda magazine Inspire and its affiliated websites. For the racist, it is Stormfront.

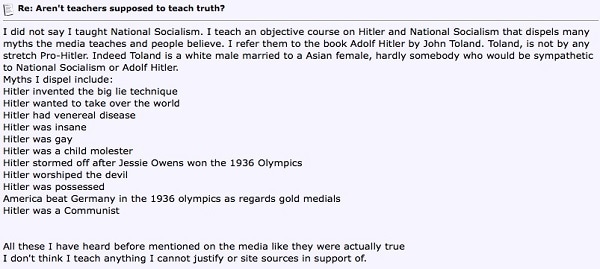

Making Excuses

Investigators find that most offenders openly advocated their ideology online for lengthy periods while sucking up the hatred around them. Yet Stormfront’s founder, former Alabama Klan leader Stephen Donald “Don” Black, shrugs off responsibility for what he has wrought.

The homicidal trend began just four years after the site went up. On Aug. 10, 1999, Buford O’Neil Furrow, a known user of Stormfront, left his parents’ home in Tacoma, Wash., and drove to Los Angeles, where he shot and wounded three children, a teenage girl and an elderly woman at a Jewish day care center. Furrow then shot and killed a Filipino-American postal worker.

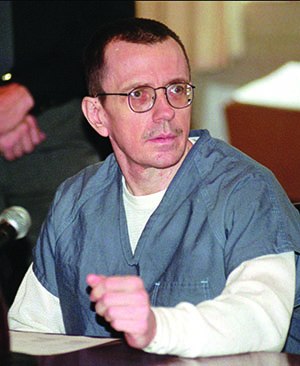

Eight months later, on April 28, 2000, just days after exchanging E-mails and a phone call with a woman he met on the Stormfront “Singles” page, Richard Scott Baumhammers shot and killed his next-door neighbor, a 63-year-old Jewish woman. Next, he drove to the victim’s synagogue, shot out the windows and painted two large red swastikas on the front of the building. And then Baumhammers went on a shooting rampage, specifically targeting minorities and murdering five people. A sixth victim would die of his injuries several months later.

When Baumhammers’ connection to Stormfront was pointed out in media reports, Black denied any responsibility. He claimed Baumhammers “had been previously diagnosed as something worse than schizophrenic.” But Black did note that attention to the killings had more than doubled the number of “hits” to his website.

On April 19, 2002, Ian Andrew Bishop, a 14-year-old so-called “Stormfront Youth” killed his brother by striking him repeatedly in the head with a claw hammer, allegedly because he thought 18-year-old Adam Bishop was gay. “He said his brother was a f—–,” said a 15-year-old witness. “He said he wanted to kill his parents, too.”

Bishop’s activity on Stormfront included downloading and distributing Third Reich images while promoting his racist views in the neighborhood. Described as a “racist bully with neo-Nazi views,” Bishop’s attorney cited his activities on Stormfront as evidence Ian was “troubled” and “drawn to the skinhead philosophy.

Again, Black denied any responsibility in the Bishop case, claiming “Bishop killed his older brother because he thought his parents liked him better. But we’re ‘responsible’ for that too,” he added sarcastically, “since he was a ‘good kid’ before visiting SF.”

The Body Count Skyrockets

The murders would keep on coming, their frequency accelerating. On Feb. 19, 2008, James “Yankee Jim” Leshkevich, who had posted more than 5,000 times to Stormfront in the preceding four years, beat and strangled his wife to death in the living room of the home they shared in West Hurley, N.Y. Then he hung himself.

Similarly, a little over two years later, on April 21, 2010, Curtis Boone Maynard shot and killed his ex-wife outside her Lake Jackson, Texas, home. He then shot his 16-year-old stepdaughter in the face, severely wounding her, before killing himself during a subsequent police chase. Maynard had posted almost 900 times on Stormfront before he was banned for publishing personal information about a black woman who had voted as a juror to acquit a black murder suspect.

Poplawski, 22, was unemployed and living with his mother when an early morning argument escalated between the two and resulted in her calling 911. Poplawski waited just behind the front door with his AK-47 assault rifle and shot and killed the first three police officers who responded. Another officer was injured before a SWAT team shot and wounded Poplawski and then took him into custody.

Fifteen weeks before the murders, Poplawski, who went by the name “Braced for Fate” on Stormfront, wrote that he kept his AK-47 “in a case within arms reach.” He’d been a registered Stormfront member for 20 months prior to the murders, but with a Web footprint going back to at least 2001. He started on pro-Second Amendment forums, moved to conspiracy pages and finally landed at Stormfront, where he had at least two user names, “Braced for Fate” and “p0p633.” An aspiring skinhead, Poplawski posted his “Iron Eagle” Nazi tattoo under his p0p633 user name in 2007, about 16 months before the killings.

The worst mass murder was still to come.

On July 22, 2011, Anders Behring Breivik set off a truck bomb in front of a government building in downtown Oslo, Norway. The blast killed eight and injured hundreds more. Dressed as a police officer and armed with a Ruger Mini-14 assault rifle and a Glock pistol, Breivik then boarded a ferry to Utoya Island, where a Workers Youth League summer camp was being held. There, Breivik shot and killed 69 people, most of them teenagers.

When he was taken into custody by a SWAT team without incident, Breivik calmly told authorities that he blamed the government for allowing Norway to be “invaded” by Muslims.

At the time of the killings, Breivik had been a registered member on Stormfront for almost three years. Under the username “year2183,” Breivik introduced himself in October 2008. In one post he wrote, “Feminism, corrupt treacherous politicians, a corrupt treacherous media, pro-immigration Jewry and a corrupt academia is the hole in the ‘dike,’ while Muslims are the water flooding in.” After a rant about Islamic enemies, Breivik was warmly welcomed by close Black confidant Freeland Roy Dunscombe, or “TruckRoy”: “glad to have you here.”

Hours before he began his terror campaign, Breivik E-mailed a copy of his racist manifesto to two other influential Stormfront members, Billy Joe Roper (see related story, p. XX) and Timothy Gallaher Murdock, who runs the racist WhiteRabbitRadio.net. In his manifesto, Breivik claimed he was banned from Stormfront, though a search shows no suspension. Breivik later admitted he was not removed as a registered member.

“I was never kicked out of Stormfront,” he said last September. “Instead, I attacked them in the compendium in order to protect them … [as] an army of leftist journalists otherwise would strike hard.”

Breivik’s large purchases of chemicals before the attack had been reported to the authorities, who took no heed because he claimed he was a farmer. If they had looked at Breivik’s posts on Stormfront, they might have felt differently. His racist vitriol and posts suggesting overthrowing his government almost certainly violated Norway’s laws against hate speech. Following the pattern for so-called “lone wolves,” he had broadcast his violent intentions ahead of time on Stormfront.

A year later, in August 2012, after Breivik was convicted and sentenced to 21 years in prison, a Stormfront thread announced the sentence and included a photograph of Breivik defiantly raising his fist in the air. Some posters lauded Breivik as a “hero” and a “P.O.W.”

Black provided his own commentary on Breivik. “Unfortunately, I happened upon this thread this morning, just before our radio show. This makes me want to pull the plug on this place and never look back,” Black wrote, before laying out a stark assessment of those on his site: “We attract too many sociopaths.”

Monetizing Murder

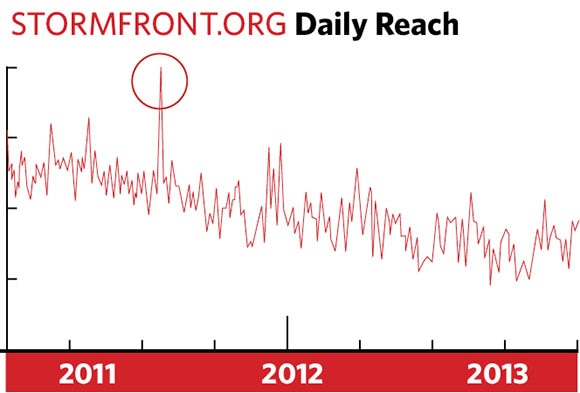

Although Stormfront posters eventually grew critical of Breivik’s actions, the public interest the attack generated on the site resulted in the highest number of registered users ever on the forum. In the 24 hours after the killings, 4,481 members were online, a record that stands to this day. Alexa, which monitors Web traffic, shows that Stormfront visits spiked globally on the day of the Oslo attacks. This means money to Black, whose banner ads pay him by the click.

A year after the Oslo terrorist attacks, in mid-summer 2012, more media came Black’s way from two more mass killings and a bizarre mutilation murder attributable to registered members.

On May 2, 2012, less than six hours after logging in and posting on Stormfront, Jason Todd Ready shot and killed four people, including an infant, before killing himself. Ready, 39, was unemployed and living with his estranged girlfriend, Lisa Mederos. He shot and killed her, her daughter Amber and her 15-month-old granddaughter, Lily. Ready then shot and killed Amber’s 24-year-old fiancée, Jim Hiott, before turning his gun on himself. Ready had made 678 posts on Stormfront in the two years prior to his death, often raising funds for his armed anti-immigrant militia group, U.S. Border Guard.

Three months after the Magnotta murder, on Aug. 5, 2012, Wade Michael Page shot and killed six people at a Sikh temple, including an 84-year-old woman, and wounded four others before killing himself during a shootout with police. Page, a longtime racist skinhead, had been a registered user on Stormfront, under various user names, for more than 10 years.

Motivational Culpability

A haggard-looking Don Black appeared on a CBS News affiliate’s newscast three days after the Sikh Temple killings. While attempting to minimize Page’s activities on Stormfront, Black said Page’s actions were “counterproductive” but then added, “We think the Sikhs should be back in Punjab.”

As Alexa Internet Inc. shows, though Stormfront’s online popularity had been in a gradual decline over the previous two years, the August 2012 Sikh temple killings resulted in one of the highest and most significant spikes of the year for the online forum (there also was a notable and rapid decline following the Sikh temple killings). And Stormfront appears to have benefited financially from the publicity that summer. Monthly donations to the site rose from $6,545 in August 2012, to $8,028 in September to $10,032 in October of that year.

A strong argument could be made that Stormfront is, in effect, monetizing murder. And Black’s personal history undermines the argument that he had no reasonable way to know how his website and the hatred he hawks was attracting and motivating a new breed of unstable, sociopathic killers. That ugly reality has been a recurring theme in Don Black’s life for almost half a century.

A Lifetime of Hate

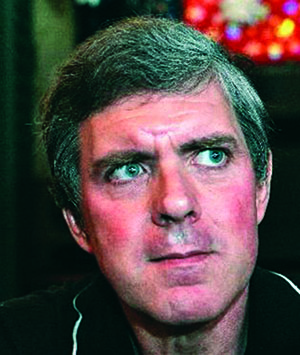

In many respects, Don Black resembles the prototypical killers that seem to be drawn to Stormfront. Black, 60, is a frustrated, unemployed white adult male living with an ideologically estranged wife, Chloe Hardin Black, who has publicly denounced the racist movement. She is the sole provider in the household.

Black spends hours every day online, utterly convinced of the supremacy of his race while expressing frustration with the inferiority of his outcomes. He occasionally complains about the sociopaths Stormfront seems to attract or laments that his only son, Derek, recently publicly denounced white supremacy.

Black’s 46-plus years of involvement with the racist movement started at the age of 15, when, like the fratricidal Ian Andrew Bishop, he began distributing racist flyers around his high school. That he was involved with a subculture of sociopaths would become quite obvious, given who Black met while on his very first “movement” road trip at the age of 16.

In the summer of 1969, Black traveled to a World Union of National Socialists meeting in Arlington, Va., in the back seat of a beat-up Chevy Chevelle, sitting next to a 19-year-old James Clayton Vaughn for more than 12 hours. Neo-Nazi and soon-to-be Klan leader David Duke was driving. As Black recollects, Vaughn was the very first person he met in the “white nationalist” movement to which he would devote his life.

Vaughn, who would change his name to Joseph Paul Franklin, later became probably the most prolific racist serial killer in U.S. history, targeting interracial couples and killing as many as 20 people in several states between 1977 and 1980 (he was convicted of eight murders). Franklin was executed last year.

Black’s exposure to the worst of the racist movement continued the following year. He spent his 17th birthday in the hospital with a bullet wound in his chest after being caught trying to steal the mailing list of the racist National States Rights Party. The shooter, Jerry Ray, was the brother of Martin Luther King Jr. assassin James Earl Ray. Jerry Ray was prosecuted for attempted murder but acquitted after claiming self-defense. Black pleaded guilty and received one year of probation.

By 1975, Black was a rising leader in the Alabama wing of David Duke’s Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, a position he kept for the next 12 years. But his ambitions went beyond the robe and hood. On April 27, 1981, Black was arrested with nine other white supremacists as they prepared to board a yacht to invade the tiny Caribbean island of Dominica, oust its black-run government, and transform it into a “white state.”

Black’s resulting three-year federal prison sentence was time well spent taking classes in computer programming. He eventually set up a dial-up bulletin board service for the radical right and, in March 1995, that service evolved into Stormfront.org, the Web’s first and best-known hate site. Black saw clearly that with this new technology, white supremacists might finally bypass the mainstream media and political apparatus he felt had long restricted the racists’ message.

“The potential of the Net for organizations and movements such as ours is enormous,” Black told a reporter in 1996. “We’re reaching tens of thousands of people who never before had access to our point of view.”

He was right.

In January 2002, Stormfront had a mere 5,000 members. But only a year later, membership had more than doubled to 11,000; and a year after that, in early 2004, it had reached 23,000. By this year, membership had hit about 286,000 registered users, though most were inactive. These numbers didn’t include the many people who simply read Stormfront postings without actually joining up (becoming a member allows one to post messages and also to view personal information.) Stormfront also became home to other hate sites that shared its servers and advertised their wares.

After a life basically monetizing ethnic hatred and death, Don Black, who walks with a cane from a 2008 stroke, has become increasingly philosophical. On the Stormfront page eulogizing serial killer Franklin, he wrote: “I may be the only person here who actually knew Franklin. I’ve been contemplating how my life would have been different had he remained the only ‘White Nationalist’ I’d ever met. I’d have quit in disgust. I had just turned sixteen, and maybe I could have then led a ‘normal’ life.”

With nearly 100 bias-related homicides attributable to registered members of his site since 2009, a great many “normal lives” are no longer being led.

Still, Black remains defiant. The theme song for his daily radio program on the Rense Radio Network is a remake of Johnny Cash’s “I Won’t Back Down.”

His wife, his son, and those who cared for the victims of racist killers connected to Stormfront probably wish he would.