In the orange light of their blazing torches, a small crowd made its way through the streets of Paris. Carrying the coats of arms of various French monarchs, the group of white French youth chanted: “Paris is our nation,” “Paris for the People, Paris for the Identitarians.”

They had gathered for the identitarians’ yearly march, held in honor of Sainte Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris who led prayers to divert the Huns away from the city in the fifth century. This year, like most years, a few hundreds had joined to walk through the city. At a stop on a street corner, an Identitarian leader addressed them:

Sainte Geneviève is with us, more than ever, and she will bring us victory. Each time you make a slogan it’s a middle finger to Islamists, it’s a middle finger to lefties.

Held on January 13, the Sainte Geneviève march is put on yearly by Paris Fierté, a group affiliated with identitarianism, the political movement centering far-right politics around calls to safeguard European identity against the perceived threats of immigration and Islam. The movement comes out of the Identitarian Bloc political party created in 2003 (now an organization known as The Identitarians), whose youth activist arm, Génération Identitaire, has since metastasized through various European countries and developed a common European group, Defend Europe.

Compared to the blatantly anti-Muslim events put on by Identitarians, the Sainte Geneviève march seemed relatively innocuous: youth blasted the French crooner Edith Piaf through the streets, mingled and drank wine and shouted relatively curated slogans. But their true ideals were not far from the surface. A group birthed by racist skinheads, the Identitarians were formed by Fabrice Robert and Phillipe Vardon, two members of the neo-Nazi oi!/hatecore punk band Fraction Hexagone, launched in 1994: Robert was its bassist, and Vardon joined as lead singer in 1999.

Birthed by racist skinheads

Fraction Hexagone was one of the key groups on the French Identitarian Rock scene whose goal was to “attract new people to nationalist ideas,” as Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg write in their book Far Right Politics in Europe. Identity rock was not about any particular genre: it regrouped a variety of styles, including oi! punk, rap, metal and acoustic ballads, and was only named as such because rock, unlike rap for instance, was perceived as affiliated to whiteness.

Fraction Hexagone (later renamed Fraction) came out of the white nationalist Rock Against Communism (RAC) tradition, born in the UK. But the band members preferred the terms Rock Against Capitalism, and perceived themselves as nationalist-revolutionary — a seemingly easy label for racist skinheads to adopt. This rebranding was part of a larger trend for post World War II fascist movements: rather than upholding Nazism or to a lesser extent Italian fascism, which came with a hefty baggage, European fascist movements rewrote fascist tradition as one of resistance to the state and the liberal order, as historian Nicolas Lebourg writes in his article, “The Productive Function of History in the Renewal of Fascism in the 1960s.”

This included cherry-picking of fascist history and appeals to leftist language, notably the language of anti-globalization and anti-capitalism. In keeping with this historical tradition, Fraction adopted the hammer and sword of the Black Front (Scharze Front) of Otto Strasser, a 1930s anti-capitalist Nazi group, as its logo. Strasser’s influence in far-right circles in France was key in helping sketch a more palatable, “leftist,” national-Bolshevik version of Nazism.

French far-right music, and French Identitarian Rock more specifically, became instrumental in developing fascist movements in the country: they helped launder a type of speech otherwise banned by law, since French speech laws, which cracked down on hate speech, allowed for more freedom of speech in art, as Kirtsten Dyck writes in her overview of white power music, Reichsrock. As Camus and Lebourg recall, Robert attempted to unite skinheads politically through his ‘zine Jeune Résistance (Young Resistance), which pushed Bolshevik-nationalist tendencies. In an interview around that time, Robert declared: “we want tracts and arms to start the social revolution in Europe.”

Fraction in its heyday was invited to perform at two concerts organized by the French far-right party, the National Front (FN), in 1996, in front of hundreds of attendees, thus attracting the attention of the government. In response to Fraction’s performance, the minister of culture Philippe Douste-Blazy called on the National Front to “clean up its act.” Fraction’s song “One Bullet” courted scandal as it called for bullets to be shot at cosmopolites, Zionists, Yankees, elected officials and the police — even the FN had had to ask the group not to perform the controversial song at their concert. Fraction, now in the public eye, was sued for incitement to hatred because of the song but the charges were eventually dropped.

Initially motivated in part by anti-Americanism, antisemitism, anti-Zionism and opposition to immigration and Islam, the members of Fraction took a solid pivot in favor of Islamophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment around 9/11. Their 2001 album, Reconquista, called for the reconquest of Europe.

Before forming the Identitarian Bloc, Robert had been quite active on the far-right, beginning when he was just 20 years old. He soon ran afoul of the law. Robert was condemned to prison in 1992 for distributing Holocaust-denial literature (and again in 2005 for defamation against a school principal.) In 1995 he was elected as a National Front representative in the French town of La Courneuve. He then joined a variety of far-right, xenophobic groups such as Nouvelle Résistance, Mouvement National Républicain and then Unité Radicale, an antisemitic group billing itself as anti-Zionist, of which Robert was one of the spokespersons. Its music label, Bleu Blanc Rock, was also heavily antisemitic.

During Fraction’s heyday, anti-Zionism held a place in the renewal of fascist ideology as leftist, which drew parallels between the genocide of Palestinians (a typically leftist cause) and the genocide of “Indo-Europeans,” which Lebourg identifies as having two principal tenets: cultural genocide (Americanization, globalization) and biological (immigration and miscegenation.) While the latter part of this ideology strongly echoes that of the Identitarians, the Palestinian side of the equation completely disappeared from view. Most of the time, however, anti-Zionism was used as a way to feed antisemitic conspiracy theories on the “Zionist Occupied Government,” also known as ZOG, basically the idea that Jewish people control the state.

In 2002, Unité Radicale, was dissolved by the state when one of its sympathizers, Maxime Brunerie, attempted to murder the French president at the time, Jacques Chirac — the day before his assassination attempt, Brunerie had posted on the neo-Nazi terrorist group Combat 18’s website: “Death to zog, 88!” (with 88 referring to the initials of Heil Hitler.) After the debacle, Robert and Vardon created the Identitarian bloc.

As Camus and Lebourg write, the Identitarian bloc led Robert and Vardon to publicly abandon antisemitism, anti-Zionism, and totalitarianism, among other views. Despite this redefinition, antisemitism sometimes crept back up. Benoit Loeuillet, the co-founder with Vardon of the Nice Identitarian group Nissa Rebella, went on to be an elected FN representative in Nice: he was suspended from the party in March 2017 after being caught on camera by an undercover journalist as he was putting forth theses shedding doubt on the Holocaust.

Repackaging old hate

As Martin Sellner and Martin Lichtsmesz, the Austrian leaders of the Identitarian movement (with Sellner the head of its European iteration, Defend Europe) told neo-masculinist Jack Donovan on his Start the World podcast, Identitarian actions serve as performance art; they aim to disrupt and influence the mainstream narrative by producing rapid fire images that the media will rebroadcast in outrage. They also attempt to unify a youth crippled by boredom in an unfulfilling consumerist society by enlisting them in a civilizational quest: the defense of Europe, described as under siege by immigration, “Islamization” and white demographic decline.

The Sainte Geneviève march, for instance, helps sell a narrative of a united French Christian civilization resisting the threat of immigrant and Muslim enemies. In keeping with the movement’s rich history of creating provocative propaganda to broaden their appeal, the march is an easy way of packaging their version of history.

Sainte Geneviève is only one of the historical figures featured in the Identitarians’ version of the European past: other icons include Leonidas, the Greek warrior-king who fought the Persian army in the fifth century BC; Charles Martel, the Frankish prince who helped defeat the Umayad caliphate troops during the 732 battle of Poitiers; or Prince Eugene, the French-born general who joined the Habsburg empire and helped win key battles against the Ottomans in the late 17th century. All inevitably feature a confrontation between a Christian “European” and a Middle Eastern or Muslim “other.”

Like their skinhead forebearers, the Identitarians position themselves as “nationalist-revolutionary.” They call for cultural rootedness and local economic and political independence from globalization, all the while framing far-right demands — such as their call for the “remigration” of Muslims and immigrants — as a defensive civilizational quest. When they yell out “Sainte Geneviève is with us,” Identitarians attempt to show themselves as young patriots stepping up where institutions have failed, a very deliberate strategy to mainstream their hateful narrative.

As Fabrice Robert explained to an enthusiastic audience at the American Renaissance conference in April 2013 near Nashville, Tennessee: “Our favorite field is street action, then relayed on the internet. It’s this combination of the two that allows us to bypass the media and break into the mainstream.” Though the Identitarian Bloc has run candidates for elections, it has been open about the fact that elections are simply a way to publicize their ideas, which is perhaps a way to excuse its electoral failures.

The tech-savvy youth arm of the Identitarians, Generation Identitaire (GI), produced a large swath of videos of their racist and Islamophobic actions, such as their 2012 launch with the occupation of a mosque in Poitiers, France. Gathering on the roof of the mosque, the group held up a banner reading “732,” the date of the battle of Poitiers, where Charles Martel defeated the army of the Muslim Umayyad caliphate. GI members allegedly urinated on prayer rugs, and could be heard shouting “In Poitiers, no kebab, no mosque,” “2012, Poitiers, we are your descendants” and “our identity, we fought to take it back, we’ll fight to defend it.”

Identitarian activists have become known for their openly Islamophobic and racist campaigns: they have demonstrated in fast food restaurants wearing pig heads and sought to interrupt public Muslim prayers with parties serving wine and pork, supposedly to denounce attacks on the French way of life. Generating outrage and internet and media attention, these events enable what Robert described “as an advertising campaign worth millions of euros for free.” In 2015, the Identitarians launched a campaign for “remigration” of immigrant populations, with the slogan: “France, we love it when you leave it” accompanied by images of a veiled woman in the subway, a group of petty criminals of Middle Eastern descent and a Muslim polygamist.

These efforts embolden Islamophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment in a country where Islamophobia can be a unifying narrative across the political spectrum. The French courts judged as much. In 2007, the Identitarian Youth, under the leadership of Philippe Vardon, was fined for its incitement to discrimination with its tracts “Ni Voilées, Ni Violées” (Neither Veiled, Nor Raped) blaming Muslim immigrants for rape. Vardon was also condemned to prison and fined because courts asserted that the Identitarian Youth, which he headed, was a resurfacing of the banned group Unité Radicale, leading to a new youth group emerging in 2012: Génération Identitaire. In December 2017, a French court condemned five members of Génération Identitaire to one year of prison and a 40,000 euro fine for incitement to racial and religious discrimination, and destruction of property for their occupation of the mosque in Poitiers. (Both parties are now appealing.)

Identitarians also provoke state and media reactions to create their narrative of the oppression of white Europeans. In 2004, for instance, they served pork soup to homeless people in a deliberate affront to Jews and Muslims. When a court deemed the activity discriminatory and illegal and prevented them from serving the soup, Generation Identitaire claimed that French homeless people were being disadvantaged and that they had to take care of “les notres avant les autres” (our own before others) because the state wasn’t doing so. The concept is central to Identitarian groups throughout France, and was most recently adopted by the far-right militant group Bastion Social (an identitarian fraction group which purports to help only French, white homeless people, and is in fact the new local iteration of the violent racist group Groupe Union Défense.) It allows groups to appear humanitarian and patriotic — even as Bastion Social’s first gathering in Strasbourg in December 2017 resulted in the violent beating up of a young French man of Algerian origin, who happened to pass by.

As the Austrian Identitarian leaders Sellner and Litchmesz reflected, quoting German nationalist philosopher Götz Kubitschek, “talking divides and actions unite.” Such actions are part and parcel of the Identitarian strategy, which aims to encapsulate a civilizational worldview in easily digestible ways, rather than lead to too much internal debate.

From media to politics

Learning from the path set by Robert and Vardon in the racist skinhead music scene, scores of younger Identitarian militants have been aestheticizing xenophobia and racism to portray themselves as courageous youth fighting for their country. Slowly, however, identitarians have been migrating to electoral politics by gaining more influence in the French far-right National Front (FN) party. Vardon, after his position as lead singer in Fraction, was long a landmark figure of far-right activism in the French southern city of Nice, for his leadership of the Nice Identitarian bloc, Nissa Rebela. The release of a video of him singing to neo-Nazi rock songs, amidst a group of skinheads breaking into what appears to be Nazi salutes, led to Vardon’s brief rebuff by the National Front party.

But after leaving the Identitarian Bloc in 2013, Vardon was elected to various regional National Front positions and made his way to a very influential role on FN presidential candidate Marine Le Pen’s campaign team, as well as in the FN branch in the southern region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur. He is only one of a group of Identitarians gaining more and more influence within the far-right party, and showing a political rapprochement between the media-savvy, youth-facing Identitarians and the older party structure of the National Front — and a move from using politics as a vehicle for conversation to actually holding office after failing to obtain electoral seats on the Identitarian platform. Vardon is especially close to Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, Marine Le Pen’s niece and the FN regional representative in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur until her departure from politics in July 2017.

It had been under Vardon’s leadership in 2007 that Identitarian Youth was condemned for discrimination after spreading Islamophobic tracts. His new career at the FN didn’t change Vardon much: in 2014, Vardon was sentenced to six months in prison for getting into a fight with three men of Maghreban origins. He claims they attacked him after recognizing him, while they claim he insulted them with racial slurs and attacked them with teargas (they were also condemned to prison.) Making no secrets of his racist views, he was caught by an undercover camera in 2017 complaining that he had had to shake the hands of too many black people while campaigning and has declared in interviews that Islam is incompatible with European civilization.

Still, Vardon and Robert both claim to have evolved, with Robert declaring “today I am no longer a nationalist, I am an Identitarian.” But the Identitarian group is not so different from Fraction’s music, as Camus and Lebourg write: Fraction was “a laboratory of forms to make popular what didn’t use to be, like the Identitarian Bloc continues to do through its very constructed agit-prop.”

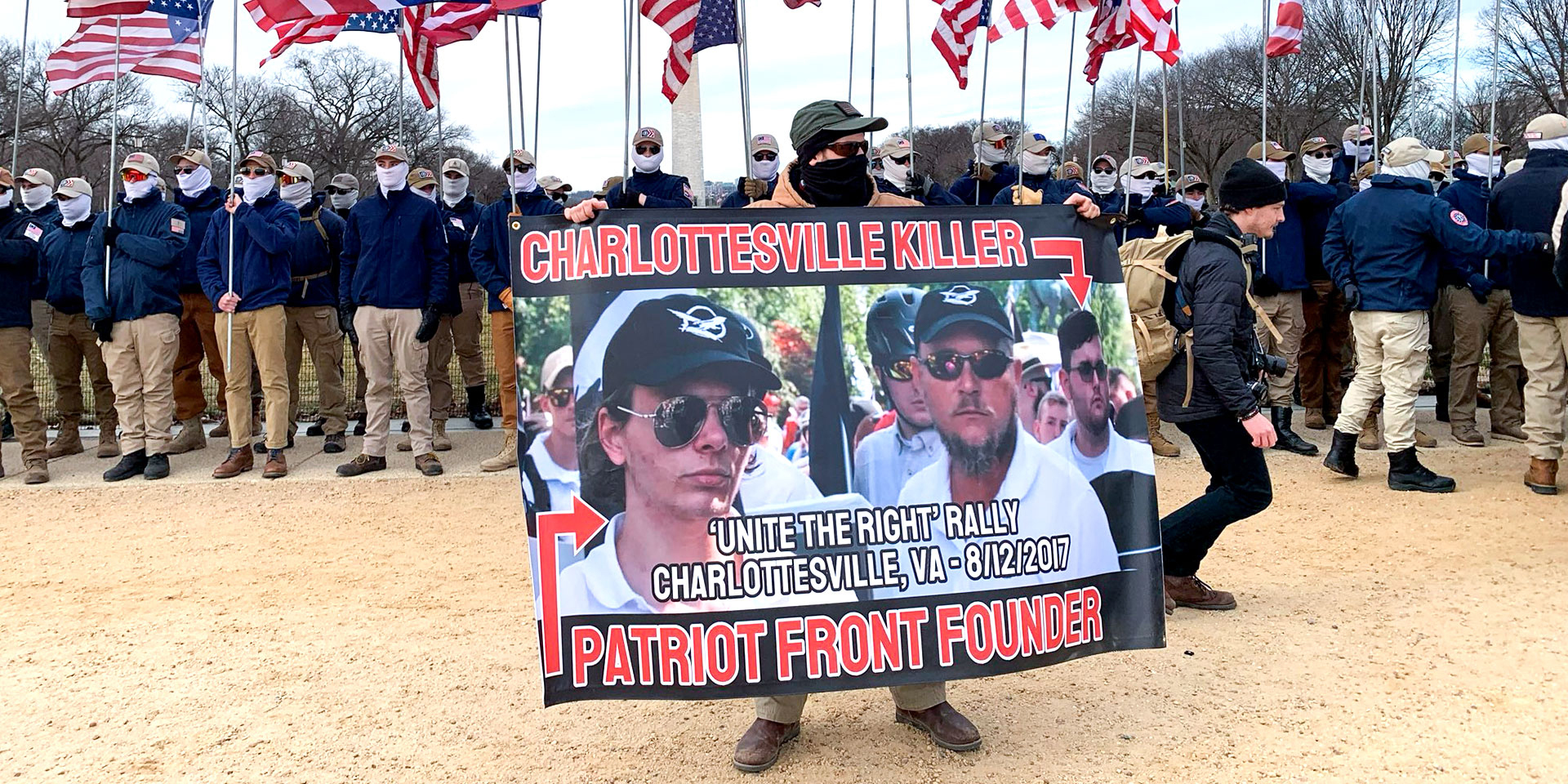

Recasting white nationalism as identitarian is a tendency that has started to creep overseas. Since appearing on Donovan’s podcast, the Austrian identitarian leader Litchtmesz spoke about Identitarian activism at the white nationalist American Renaissance conference in July 2017, and identitarian leader Martin Sellner has become a favorite of American alt-right YouTubers and podcasts. As a result, identitarian methods and language have begun emerging in the U.S.: Identity Evropa, a white nationalist group, started using the term “identitarianism” and started using Identitarian propaganda methods. In December 2017, for instance, they set up memorials for Kate Steinle to protest the acquittal of the undocumented man who shot and killed her in July 2015 — the case became a cause célèbre among white nationalists.

Identitarian strategies are here to stay. But whether they call them PR or performance art, it is hard to be fooled — it’s still the same old hate, and hardly in sheep’s clothing.

Photo credit: MATTHIEU ALEXANDRE/AFP/Getty Images