As a light rain fell from an overcast sky, aging neo-Nazi and racist David Duke stood in an electric blue blazer checking his phone while holding a sign saying “Support our Monument” in central Alabama.

Duke trekked to the town of Wetumpka, population 6,500, on April 7 to celebrate the one-time Ku Klux Klan leader’s 50 years in the white supremacist movement with the League of the South.

The shindig was billed as a public demonstration and mini-conference, which was closed to the general public.

Duke, for his part, waved at passing cars at the intersection of U.S. 231 and Alabama Highway 14, smiled to the few who gave the gathering thumbs up and appeared to try to stay engaged.

The public part of the day, didn’t last long — about 50 minutes or roughly one minute for each year of Duke’s racist career. Rain sprinkled off and on before the skies opened up on the Confederate flag-waving League of the South members — decked out in black shirts and khaki pants — and they decided to pack it in.

On Twitter and the racist “alt-right” social network Gab, League of the South founder Michael Hill and several members declared the demonstration a success.

“It was good to be with compatriot Dr. David Duke this weekend as we honored him for 50 years of service to his people and civilization,” Hill captioned a photo of him with his arm around Duke.

But those honoring Duke turned out to be all wet.

An early start

At 67 years old Duke, an Oklahoma native, started appearing publicly as a racist on the campus of Louisiana State University (LSU) in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he formed a white student group called the White Youth Alliance in 1970. The group was affiliated with the National Socialist White People’s Party, which advocated for an “Aryan homeland” in the Pacific Northwest.

After graduating from LSU in 1974 with a degree in history, Duke founded the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Duke floated around the fringe of politics and relevancy for the rest of the decade, running for state Senate and even President of the United States in 1979. He also formed the National Association for the Advancement of White People as he sought separation from the Klan and its reputation and got into tussles with other racists over his fundraising methods and how he handled finances.

In 1979 Duke’s Florida state leader, Jack Gregory, told the Clearwater Sun newspaper that Duke refused to turn over the proceeds from a series of Klan rallies to the Knights organization.

“Duke is nothing but a con artist,” Gregory said.

At one point in the 1980s, Duke had become so irrelevant that, according to journalist and Duke biographer Tyler Bridges, he was regularly seen on weekdays playing the public golf courses at City Park in New Orleans.

A political rise

Duke resurfaced in 1989, running for a legislative seat in a heavily white, older district in Metairie, a suburb of New Orleans. By this point, Duke switched to the Republican Party (he had previously run as a Democrat when Louisiana was a heavily Democratic state), and changed his looks away from the tall, skinny guy with a non-descript face and straight brown hair swept to the side.

The re-emergence brought a new look — pressed shirts, red ties and blue suits along with a new nose, prominent chin and carefully coiffed blonde hair.

Duke also repackaged his ideas. Instead of talk about J— and n——, Duke took to using more standard Republican language, pushing the idea that welfare recipients should be drug tested to receive any benefits and talk about how he was proud of his heritage.

It was technique that other neo-Nazis and, more recently, members of the alt-right would come to copy.

Two years in the legislature came with three more political races for Duke — U.S. Senate, Governor of Louisiana and a challenge in 1992 to George H.W. Bush for the GOP nomination for president.

Each fizzled, as did Duke’s relevance on the political and racist scene.

A fall … and a return

While keeping the physical enhancements that went with the political rise, Duke returned to his roots as a full antisemite and racist in 1998, with a book called My Awakening. He dropped the coded language and laid out the reasoning behind his push for white supremacy and white separatism.

After three years in Russia and eastern Europe, Duke returned to the United States in 2002 and pleaded guilty to filing a false tax return and mail fraud.

Duke called it a conspiracy. The Internal Revenue Service called it fraud, deception and a crime.

The charges stemmed from Duke’s pitch from 1993 through 1999 to supporters, telling them he was in dire financial straits, then using the money raised to fund gambling trips.

Duke spent 15 months in federal prison in Big Spring, Texas, before being released in May 2004.

Since getting out of prison, Duke has sought to rehabilitate his reputation among racists and has made an attempt to stay relevant.

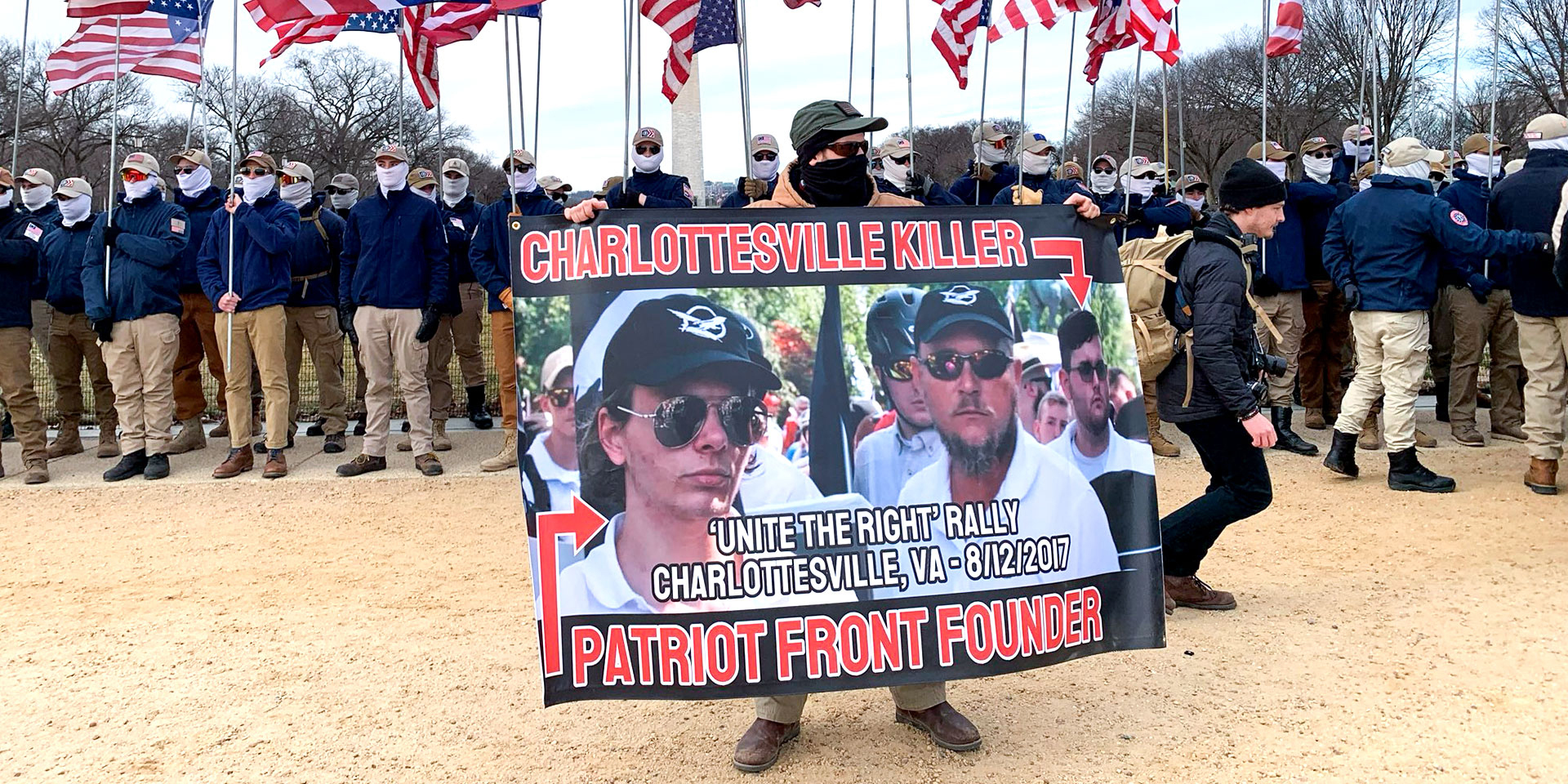

He endorsed Donald Trump for president — a move that caused the then-candidate no end of headaches — and backed Trump in August 2017 when the president said there were “good people” on “both sides” of the deadly Unite The Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017.

“Thank you President Trump for your honesty & courage to tell the truth about #Charlottesville,” Duke tweeted.

As Duke latched on to Trump, he became something of a grandfather figure to the racist alt-right, some of whom adopted Duke’s well-honed tactics.

It is rare these days to see a racist in a sheet with a cross inside a red circle parading around, much as Duke did in his Klan days.

Instead, the modern neo-Nazi, alt-right racist is likely to be in a clean, collared shirt, with a short haircut looking like a salesman or a local television news reporter.

It’s the same cosmetic appeal Duke made almost 30 years ago. The alt-right adopting Duke’s look and rhetorical gimmicks — staying calm, couching racism and antisemitism in philosophical and politically palatable terms — has brought the aging Nazi’s career full circle.

Celebrating a racist career

Hill invited Duke to the organization’s headquarters just outside Wetumpka on April 7 to celebrate Duke’s work on “behalf of our people and civilization.”

During the flag waving rally on Saturday, Duke chatted with League of the South members and repeatedly checked his phone.

Once the rain started heavily, the neo-Confederates vanished up the road into the League of the South headquarters to hear Hill speak.

Duke, once the premier white supremacist in America, drew large crowds and cheers during his heyday. It isn’t known if he spoke to the gathering in Wetumpka.

But now, Duke was left fleeing the rain in rural Alabama.

It seems the ideal fit as he tries to stay relevant in the racist movement.