“We can’t be afraid to be normal,” James Allsup, a scheduled speaker at last year’s Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, told the hosts of a popular white nationalist podcast, “Exodus Americanus,” in June.

He was there to sell an idea that, until recently, most members of the racist “alt-right” abhorred: painting themselves as the defenders of “traditional” values, joining local GOP parties and, in effect, abandoning their “edgelord” status. Allsup himself recently became a precinct committee officer for the Whitman County, Washington, Republican Party.

Among some of the most prominent voices in the alt-right, Allsup is being held up as a model for the future. The countercultural online movement has marked electoral politics, especially at the local level, as the newest frontier for advancing the white nationalist agenda.

This shift is partially strategic: Local politics have a low entry barrier and offer real opportunities to shape party priorities and leadership. But the focus on institutions is also part of a wider attempt to rescue the alt-right after last year’s deadly rally in Charlottesville.

The Unite the Right rally was meant to mark the movement’s arrival as a unified, viable political force, but instead ended up irreparably marring its image. The fact that only a couple dozen white supremacists turned out to the Unite the Right 2018 event marking the rally’s one-year anniversary stands as proof that street action carried under the banner of overt white nationalism is no longer viewed as an effective tactic.

It would be a mistake to consider this poor showing a sign that the alt-right is dead. The truth is that the movement to still very much alive — it’s just made some tactical shifts.

Now, the alt-right is banking on the possibility that they’ll be able to slowly pull members of the GOP toward their own brand of nationalism, where the thread stitching together members of the polity is not shared democratic ideals but race. President Trump has already made immigration and border security major issues, and figures like Allsup see it as an opening: with nativist talking points already in the political mainstream, how difficult could it be to convince people that not just closed borders, but also policies aimed expressly at solidifying white hegemony, are the best way forward?

Allsup’s forerunners

Allsup has been pushing for members of the alt-right to “take over” the Republican Party since he was a student at Washington State University, where, in his words, he ascended within the College Republicans chapter by “waging war against the GOP establishment c—-.” Allsup had earlier models to look to, including figures like Pat Buchanan — the paleoconservative who, during his three presidential campaigns from 1992 to 2000, ran on a hard anti-immigrant and isolationist agenda that played on America’s fears of demographic change. Buchanan took on the role of an insurgent, operating within Conservative circles while criticizing the Republican Party for being elitist and out of touch.

Allsup has also built on more recent models of politicking, and ones that were closer to home. On the same campus where Allsup got his start, Phil Tignino organized a chapter of the white nationalist Youth for Western Civilization (YWC) campus network nearly 10 years ago. It was an early forerunner to today’s campus-based white nationalist groups like Identity Evropa (IE), with nearly a dozen chapters around the country agitating “to revive Western civilization and make it the dominant culture in the United States.” Individuals such as Devin Saucier and Matthew Heimbach made their debuts within organized white supremacy via their involvement with YWC.

While president of the WSU College Republicans from 2015 to 2017, Allsup helped erect a “Trump wall” at the University of Washington and invited the alt-right troll Milo Yiannopoulos to speak on his campus. But those were hardly new tactics: YWC also invited speakers like (the then relatively unknown) Richard Spencer to universities. In 2011, Tignino even erected his own wall on WSU’s campus — aimed at demonstrating the need to keep immigrants out of the country — long before chants to build one on the southern border animated attendees at Trump rallies.

YWC made some brief inroads into mainstream conservative circles, hosting panels on immigration at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in 2009 and 2011, but ultimately wasn’t able to get far beyond the fringes. The landscape looks different now, and Allsup is coming to politics in a moment far friendlier to white nationalist ideas.

For Allsup, the party of Trump looks like the best venue to build support for his agenda and make new recruits.

“If you have three or four fashy goy friends, you can take over your school’s College Republicans group and move it to essentially being an alt-right club,” Allsup explained in a 2017 episode of the white nationalist podcast “Fash the Nation.” Doing so offered numerous benefits that membership in an explicitly white nationalist group did not, including greater access to resources, credibility and all of the “things that come along with the name of being a Republican.”

Allsup’s tenure as president of the College Republicans came to an end after he appeared at the 2017 Unite the Right rally, where his livestream showed him excitedly greeting and thanking one of the event’s organizers, Richard Spencer. But it was only a minor setback in his ascent within the alt-right.

After stepping down from his post as president, Allsup set his sights on growing his online presence. On his YouTube channel — which currently has more than 300,000 subscribers — Allsup posts explainer videos in which he mocks left-wing politics while arguing that they distract from the true political crisis plaguing the United States: the demographic displacement of whites. His hundreds of videos include alarmist titles like “Thousands of Migrants Prepare to Invade America” and “ANTIFA PROFESSOR Gets Away With ASSAULT!”

“We can’t all be Andrew Anglin”

Even while focusing on content creation, Allsup argued that “metapolitics” — a term borrowed from the French New Right to describe efforts to transform political structures by first remodeling the nation’s cultural values — was never truly enough to shift society toward their white nationalist vision. That idea is a marked shift in the direction of the alt-right, which has for several years now been a movement that’s prided itself on creating its own media platforms, insider humor and cultural references. Transgression has been an asset for the alt-right, whose eschewal of the stodginess typically associated with conservatism has — with the assistance of the internet — helped broaden their appeal among a younger set of potential recruits.

But Allsup and others have started to grow bored of operating mostly within their own echo chambers, while recognizing that their dreams of undoing the current political norms might require them to first work within their confines. “We cannot podcast, livestream, or tweet our way to victory. We can only change consciousness so much before we have to start changing the political infrastructure,” Allsup told the audience at a March conference hosted by Identity Evropa, the “identitarian” group he joined early this year that the SPLC designates as a hate group.

In that speech and several recent appearances on white nationalist podcasts, Allsup laid out his strategies to build political power.

The first step, according to Allsup, is to downplay the extreme nature of their ideas. Leave out the fact that the alt-right wants to create a whites-only ethnostate and instead focus on more benign talking points, emphasizing their beliefs “in family, tradition, heritage, the idea that it’s okay to be white, strong borders, [and] protection of America’s founding stock.” Doing so, Allsup has continually emphasized, creates plausible deniability. While keeping their rhetoric within the realm of acceptable prejudice, they can promote policies aimed at achieving racial purity while never saying so and giving the game away.

Given their limited resources, Allsup and his ilk argue that the most effective way for white nationalists to spread those ideas is not by building their own political institutions but by co-opting the GOP from the ground up. In June, Allsup made that step within his own local party when he ran for an uncontested seat to become a precinct committee officer for Whitman County, a position that will allow him to conduct voter outreach, facilitate voter registration and help steer the direction of the county party.

While being involved with the local party, Allsup insists he’s not a “shill for the GOP,” and is in fact highly critical of the party for “virtue signaling.” While the GOP makes every attempt to steer clear of anything resembling “identity politics,” Allsup insists that the Republican base is actually craving that kind of discourse — or, more specifically, they want to talk about the perceived injustices committed against white people. “There’s a lot of them who are way more woke than you can imagine,” he told the hosts of the popular neo-Nazi podcast “The Daily Shoah” in mid-June, before telling a story about meeting a stranger at a party fundraiser who appeared to share his same conspiratorial beliefs about Jews.

The evidence that people will respond to these kinds of racial appeals abounds. More than half of white people believe they face discrimination today. And, of course, Donald Trump’s presidency is built on racist appeals to white grievances. While he tapped into already existing racial animosity, recent research shows that Trump’s rhetoric has actually emboldened people to embrace more bigoted ideas themselves.

The point of joining local parties is then not only to seed members of the alt-right into the mainstream political establishment, but to encourage others in those spaces to air their own racial grievances and prejudices — which will, in turn, invite more alt-righters into those spaces. “Maybe you’re just the guy who stands up and says, ‘You know what? I don’t want immigrants. I don’t think we need to bring any here.’ So that the other five people who feel that way — you’ve given them permission to now have that conversation,” Jim “Based Atlanta” told Allsup and his other cohosts on “Exodus Americanus.”

In each of his appearances on white nationalist podcasts, Allsup has received enthusiastic support for his strategic vision. “If you’re a registered Republican, which I’m guessing most of you are,” Mike “Enoch” Peinovich told his audience, “see if you can grab a local seat and shift politics in our direction at the local level. I mean, why not? You don’t have to out yourself as anything.”

“We can’t all be Andrew Anglin,” Jim “Based Atlanta” noted, “but 10,000 of us can be James Allsup.”

“You might not be the guy who swings the nation or who swings the Overton window. But if there’s 10,000 of us or 1,000 of us, the cumulative effect of all of those little influences can really change things. I think that’s the next step for us.”

Grooming tomorrow’s alt-right leaders

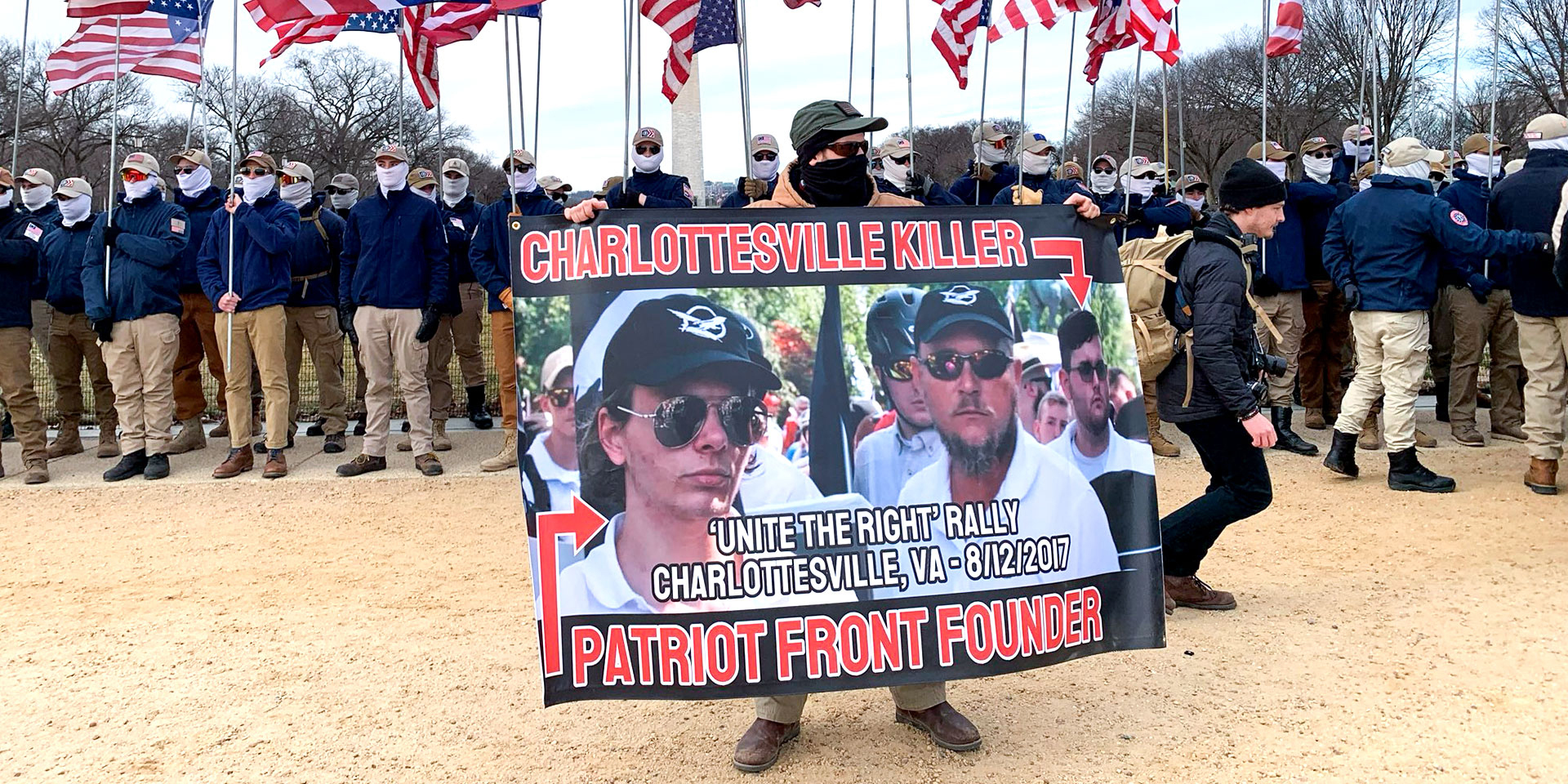

Allsup is far from the only white nationalist calling for his comrades to look to electoral politics. Identity Evropa has been shifting in that direction since last year’s events in Charlottesville, which both the group’s founder, Nathan Damigo, and Elliot Kline, who took over when Damigo stepped down, helped plan. More than any other organization present that day, IE made measured strategic changes designed to help weather the backlash that followed.

Identity Evropa, which now boasts Allsup as one of its most prominent members, skews young, organizing men (mostly) and women on college campuses into local chapters that aim to ensure that white people “retain demographic supermajorities in our homeland.” They were founded with a focus on real world activism and, more and more, this means actively grooming members to follow the kind of path laid out by Allsup: they encourage members to get engaged with local politics and ally with the GOP in order to slowly build an alt-right base within the party.

Patrick Casey, who took over IE’s leadership late last year after Kline stepped down, tightly manages his organization. Chapters no longer attend big-tent events like the Shelbyville, Tennesee, White Lives Matter rally held in October 2017 (which Damigo called “cringe” and “unmarketable”). Under Casey’s watch, IE holds “flash mob” demonstrations — usually displaying banners with slogans like “Stop the invasion, end immigration” — that are unannounced only in order to avoid attracting both counter-protesters and out-and-out neo-Nazis. They come well dressed to public events, engage in (and endlessly document) community service work like park clean-ups and talk not about hatred but about protecting their own race. As “identitarians” they claim not to be interested in maintaining white supremacy, but advocate for an “ethno-pluralistic” society in which all ethnic groups live separately.

IE’s efforts go beyond their polished appearances and toned-down rhetoric — both features that have helped the organization come out on top in the “optics war” that raged in the year following Unite the Right.

On a podcast, Casey recently invited on Alex Witoslawski, a conservative-turned-“dissident right” political operative, to lay out the basics of grassroots organizing for IE members. Witoslawski was trained by the Leadership Institute, a multi-million-dollar non-profit that “teaches conservative Americans how to influence policy through direct participation, activism, and leadership.” The organization also helped launch YWC.

Casey said in April that the organization’s primary goal is to prove that “we — or people with our views — are worthy of having power.”

“I am totally in support of people getting involved in not only their local Republican Party chapter but also organizations like the College Young Republicans,” Casey told the host of the podcast “A Comfy Tangent” in June, “even the goofier ones like, you know, Turning Point and so forth.”

“We do have people who are very active in their local Republican Party chapters in addition to the other clubs that I just named,” he added.

The strategy behind filtering white nationalists into mainstream political organizations goes beyond gaining power and resources — it also simply provides people with something to do. With any social movement, providing tangible ways to support the cause and realize goals can lead to greater mobilization and engagement. And not only does joining your local Republican party provide Allsup and Casey’s followers with a sense that they’re furthering their movement, but it allows them to do so without paying the social costs that come with being an open white nationalist.

There’s recent evidence that members of IE, who are notoriously secretive about their affiliation with the group, have been working to promote Republican candidates. At the beginning of the month, the Topeka Capital-Journal reported that three young men who were members of American Heritage Initiative, an offshoot of IE, were working as consultants for Kris Kobach’s Kansas gubernatorial campaign.

What’s acceptable within the GOP has shifted dramatically since Trump’s ascent. Candidates like Corey Stewart — a Trump-endorsed, pro-Confederate Virginia gubernatorial candidate who once palled around with neo-Nazi Paul Nehlen — are running in major races, and so are a number of outright white nationalists. Without some major sea change, racist ideas will continue to infect the GOP, and white nationalists like Allsup and his followers will be there to try to keep the momentum going.