In this video: Rivka Maizlish, a senior research analyst for the SPLC’s Intelligence Project, speaks during an interview with CBS Evening News about the need to remove Confederate symbols from public spaces.

More than three years ago, an overwhelming bipartisan majority in Congress passed a bill mandating the removal of all Confederate symbols from military property by Jan. 1, 2024.

The effort has provided an eye-opening example of how deeply embedded Confederate iconography is within the United States. The federal commission identified 800 Confederate symbols on U.S. military property to be removed by the deadline. These symbols include items such as the names of roads on military bases, flags, busts and insignia.

Our nation renamed 10 military bases bearing the names of Confederates – men who committed treason. Those bases received new names honoring U.S. veterans or values last year in time to meet the Jan. 1 deadline.

The effort brought attention to a Confederate monument on the grounds of Arlington National Cemetery, the final resting place for people who served our nation. While this Confederate monument had disgraced our national burial ground since 1915, it has finally been removed.

The path to its removal, however, demonstrates the difficulties of eradicating Confederate iconography – even when it’s backed by an act of Congress.

Supporters of the monument first claimed that the memorial was a symbol of unity. In fact, the memorial was part of an organized propaganda campaign to rewrite the history of the American Civil War. Before and during the war, Confederate leaders explicitly stated that they fought for slavery and white supremacy. After the war, groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who sponsored the Arlington memorial, worked to erase ideological differences between the Confederacy and Union.

These groups created the myth that the war had not been a struggle between slavery and freedom. Essential to this myth was the lie that enslaved people were happy. The Arlington memorial promoted this lie with its racist depictions of enslaved people, such as the image of a Black “mammy” taking a child from a Confederate soldier.

Second, the memorial’s defenders claimed its removal would erase history. In fact, its presence in our national cemetery was part of an effort to erase history, including the history of the Black and white soldiers – buried in Arlington and all around the country – who died for the emancipation of enslaved people.

When the true history and meaning of the Confederate memorial at Arlington became clear, its supporters, in desperation, claimed removal would damage surrounding graves. On Dec.18, supporters of the memorial sought to block its removal based on claims about desecrated gravesites. The next day, U.S. District Judge Rossie Alston toured the site at Arlington, and found that “the grass wasn’t even disturbed.” He allowed the removal to proceed.

While the Southern Poverty Law Center commends the removal of the monument, there is much work left to be done, as all 800 symbols on military property have yet to be removed. What’s more, the SPLC’s Whose Heritage? project has identified more than 2,000 symbols dotting public areas across the U.S., such as monuments in town squares and the names of schools and roads.

These symbols distort history by perpetuating a myth that sanitizes the Civil War and celebrates traitors who supported a white supremacist regime. It may be a long, arduous task, but Confederate symbols must be removed. And people must speak up and support their removal.

Rivka Maizlish is a senior research analyst for the SPLC’s Intelligence Project.

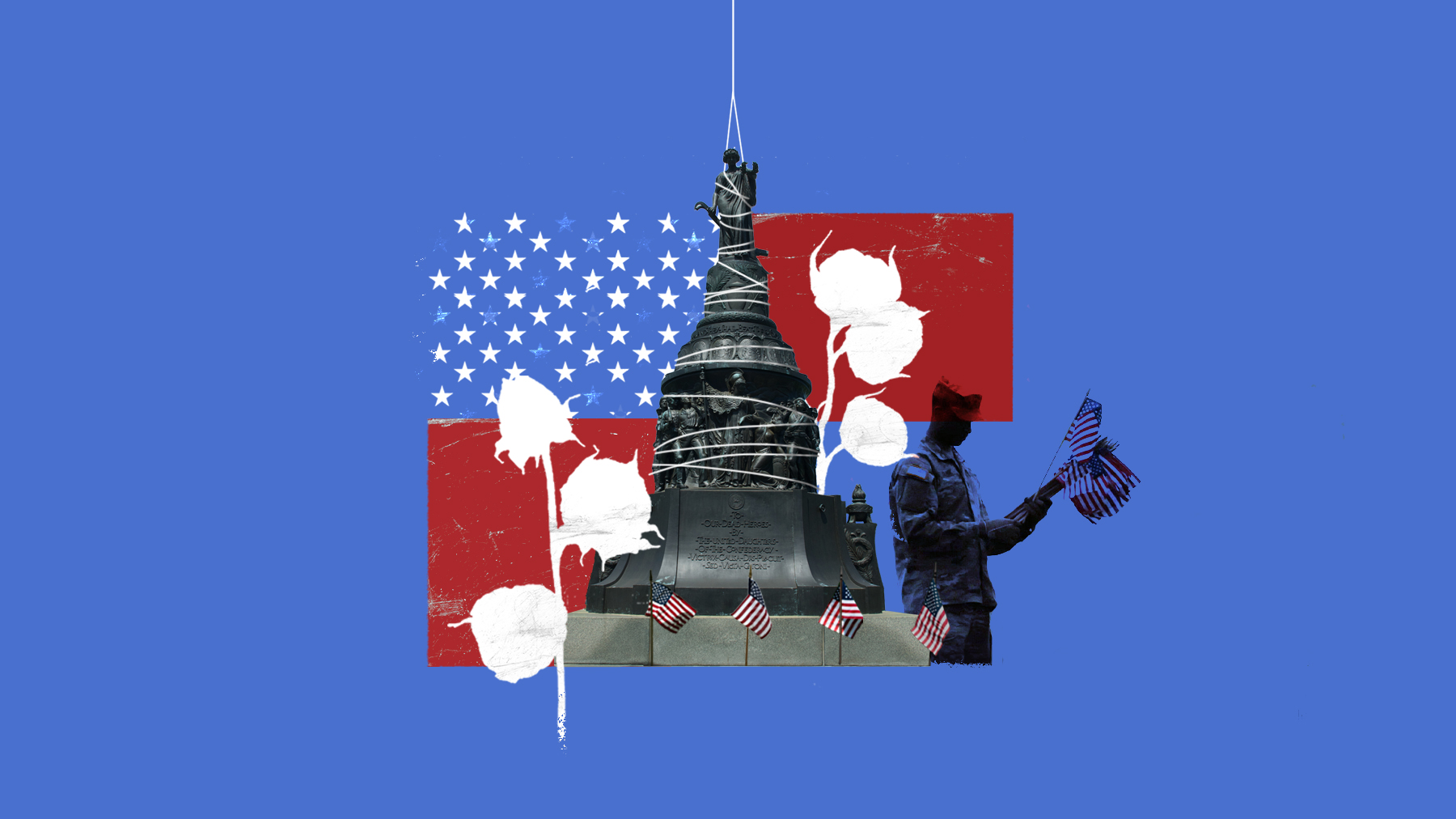

Illustration by Alex Trott, SPLC.