Last month, the New Orleans City Council voted to take down four monuments honoring the Confederacy and its heroes, resulting in a federal court challenge by preservation groups and a chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

This week, the Southern Poverty Law Center and several New Orleans lawyers filed an amicus brief (PDF) in the case that provides a fascinating historical account of the monuments’ connections to the region’s shameful history of violence and terror in support of white supremacy.

Read some of the more important excerpts of the brief below:

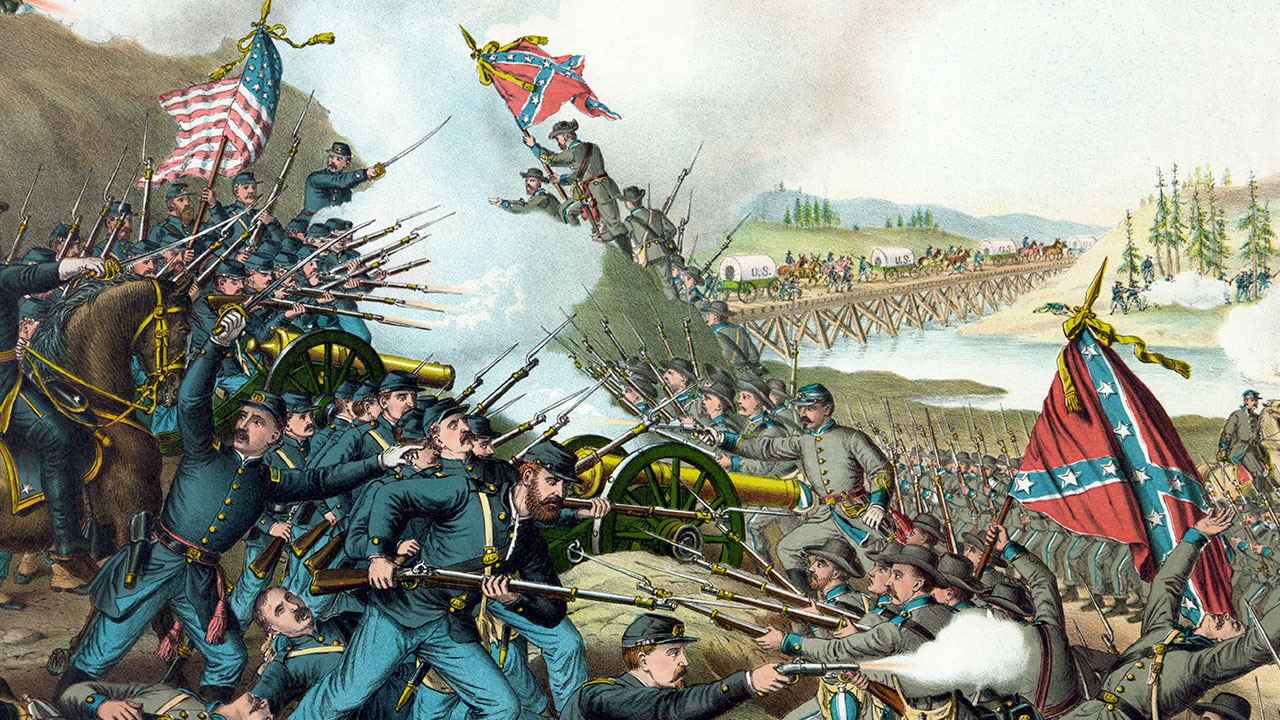

The Civil War Was A Violent, Treasonous Campaign Of Terror To Preserve Slavery And White Supremacy; White Terror And Domination Continued After The Civil War

The monuments at issue in this case honor and glorify the Southern Confederacy. Therefore, it is with the Confederacy that this analysis must begin.

Louisiana’s antebellum economy and social order were rooted in the twin institutions of African slavery and white supremacy. In 1860, Louisiana had a total population of 708,002, of which 47 percent were enslaved, and the entire pre-war Louisiana legal system was based on maintaining white supremacy in every phase of life. In its colonial days, the 1724 Code Noir disenfranchised all blacks; when Louisiana became a state in 1812 its constitution limited the right to vote to free white male citizens who owned property or paid taxes. Subsequent laws limited voting to free white males until after the Civil War. As respected Louisiana federal jurist Judge John Minor Wisdom pointed out over fifty years ago, Louisiana social history is rooted in “the dominant white citizens’ firm determination to maintain white supremacy in state and local governments by denying to Negroes the right to vote.”

The Confederate cause in the Civil War was a tremendously violent campaign to hold onto this legal institution of white supremacy. The historical record is clear that the Southern states seceded from the Union and engaged in a treasonous war against the United States government because they were determined to retain the legal right to own, buy, sell, and sexually and physically abuse black human beings. There is no historical basis for the position that the Civil War was fought over anything other than the South’s determination to retain the institution of chattel slavery. “Beyond ideology lay naked economic and political interests because southern white elites needed cheap labor akin to that provided by slaves if they were to remain a ruling aristocracy.”

Indeed, Louisiana representatives openly identified slavery as the reason for secession:

As a separate republic, Louisiana remembers too well the whisperings of European diplomacy for the abolition of slavery in the times of an-nexation not to be apprehensive of bolder demonstrations from the same quarter and the North in this country. The people of the slave holding States are bound together by the same necessity and determination to preserve African slavery.

Slavery and the supremacy of whites was the essence of the struggle.

Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution of the Confederate States stated:

In all such territory the institution of negro slavery, as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected be Congress and by the Territorial government; and the inhabitants of the several Confederate States and Territories shall have the right to take to such Territory any slaves lawfully held by them in any of the States or Territories of the Confederate States.

The Confederates lost. The violence and terror of the Civil War resulted in massive death and damage to the country. About 750,000 people died in the Civil War, leaving hundreds of thousands of widows and orphans. As a result of that defeat, Louisiana was faced with a new power bloc in voting—its African American population, who comprised nearly half of its census. Though clearly reluctant to do so, Louisiana authorized black men to vote.

The losers of the Civil War, however, were not prepared to give up their political power, their way of life, or their property. Many of the former Confederates took on armed resistance against the new regime, and by 1898, white Louisianans managed by politics, violence and terror to reinstitute white supremacy in political power and daily life. Black voters, who had only been allowed to vote since 1865, were officially disenfranchised again through an amendment to the state constitution that erected educational, literacy, and property qualifications for those who wished to vote unless exempted by the grandfather clause. This act of racist disenfranchisement was done openly. The chair of the 1898 convention declared: “We (meet) here to establish the supremacy of the white race, and the white race constitutes the Democratic party of this State.”

As Judge Minor pointed out in his 1963 opinion, “[t]he Convention of 1898 interpreted its mandate from the people to be, to disfranchise as many Negroes and as few whites as possible.” The constitutional amendment had its intended effect of reducing black voters from 130,344 in 1897 to 5,320 in 1900. By 1910, black voter registration had been further reduced to 730 people in Louisiana, or less than 0.5 per cent. White supremacy was back; black citizens were again subordinated and suppressed.

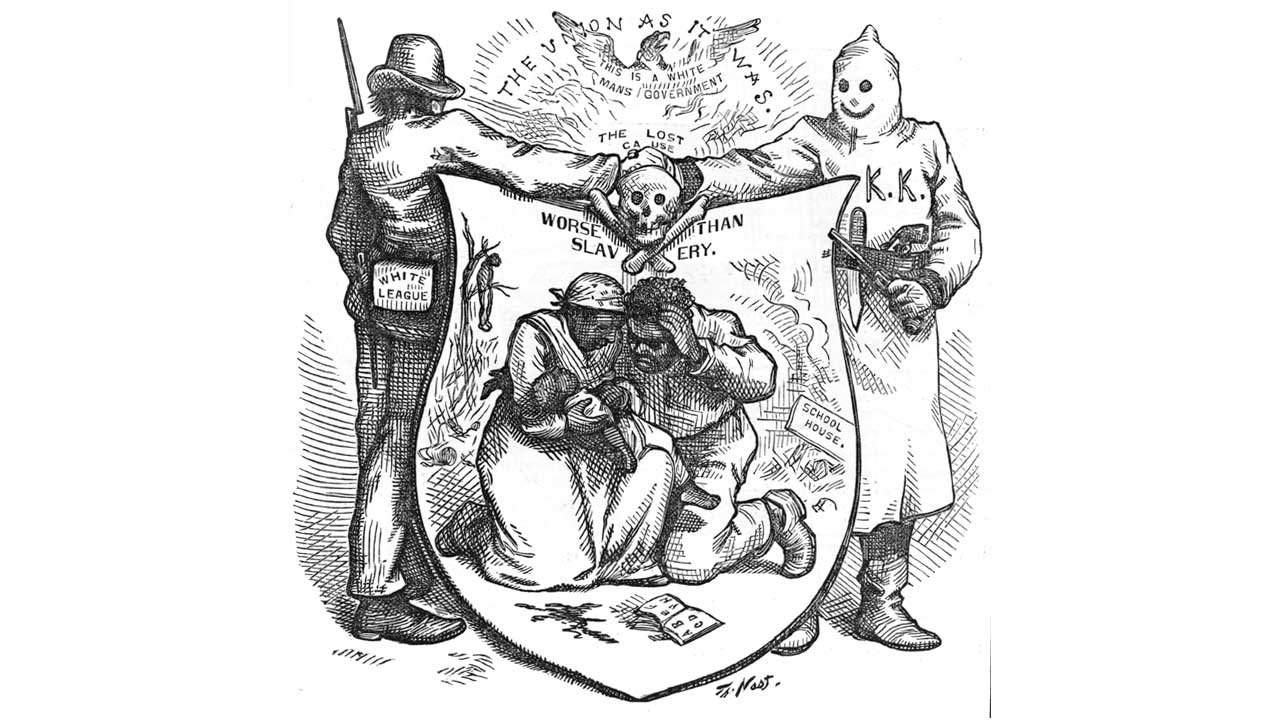

The white South also sought to revise the history of the Civil War by creating a new and inaccurate narrative that 1) cast the Confederacy as a noble and praiseworthy cause; 2) denied the central role that slavery played in causing the Civil War; and 3) downplayed the brutal reality of American slavery.

“In this revision of the past, the antebellum South was recalled as a benevolent, orderly society that pitted its noble values against the aggressive greed of northern industrial society. Denying slavery as the root cause of the war, the proponents of the Lost Cause achieved an ideological victory – even as the South was defeated in the war – by shaping the popular memory of the conflict. In the process, this ideological victory helped insure widespread American acceptance of the South’s justification for the racial status quo.” -— Eric Foner, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation & Reconstruction 216 (2005).

This distortion of history, crafted by white southerners, is a phenomenon that historians now call the Cult of the Lost Cause.

According to documents filed with the National Register of Historic Places:

The Cult of the Lost Cause has its roots in the Southern search for justification and the need to find a substitute for victory in the Civil War. In attempting to deal with defeat, Southerners created an image of the war as a great heroic epic. A major theme in the Cult of the Lost Cause was the clash of two civilizations, one inferior to the other. The North, ‘invigorated’ by constant struggle with nature, had become materialistic, grasping for wealth and power. The South had a ‘more generous climate’, which had led to a finer society based upon ‘veracity and honor in man, chastity and fidelity in women.’ Like tragic heroes, Southerners had waged a noble but doomed struggle to preserve their superior civilization. There was an element of chivalry in the way the South had fought, achieving noteworthy victories against staggering odds. This was the ‘Lost Cause’ as the late nineteenth century saw it, and a whole generation of Southerners set about glorifying and celebrating it. Glorification took many forms, including speeches, organizations such as the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, reunions, publications, holidays such as Lee’s birthday, and innumerable memorials.

The six main assertions of the Cult are:

Secession, not slavery, caused the Civil War; African Americans were “faithful slaves,” loyal to their masters and the Confederate cause and unprepared for the responsibilities of freedom; the Confederacy was defeated militarily only because of the Union’s overwhelming advantages in men and resources; Confederate soldiers were heroic and saintly; the most heroic and saintly of all Confederates, perhaps of all Americans, was Robert E. Lee; and Southern women were loyal to the Confederate cause and sanctified by the sacrifice of their loved ones.

This was the “Lost Cause” as the late nineteenth century saw it, and a whole generation of Southerners set about glorifying and celebrating it. Glorification took many forms, including speeches, organizations such as the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, reunions, publications, holidays such as Lee’s birthday, and innumerable memorials.

The Cult of the Lost Cause continued to dominate Southern cultural history in the early twentieth century, and it is indeed still alive and well today. If the Court has the occasion to review the public hearings held by the City of New Orleans over the removal of these statues, it will find nearly every one of the core assertions of the Cult of the Lost Cause was repeated, often more than once, by the white southerners who objected to the removal of these monuments.

Moreover, three of the statues at issue in this case have been described by the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism as THE major monuments in New Orleans representing the Cult of the Lost Cause—the monuments of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and P.G.T. Beauregard. It is not by accident that these three monuments were erected and venerated. They were elevated to honor the violent, treasonous war to retain white supremacy and to legitimize those who continue to seek it.

The Cult of the Lost Cause is not, as its past and present advocates contend, a benevolent historical tribute to Confederate veterans. Rather, the Cult of the Lost Cause was at the heart of the ideology of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacy groups that portrayed the emancipated African American as a threat to democracy and white womanhood. It also sought to return Louisiana to its pre-Civil War days of total white control and supremacy.

This is the historical context in which these monuments to white supremacy were erected and are maintained. This context is essential to this court’s evaluation of whether these monuments should continue to stand in New Orleans.

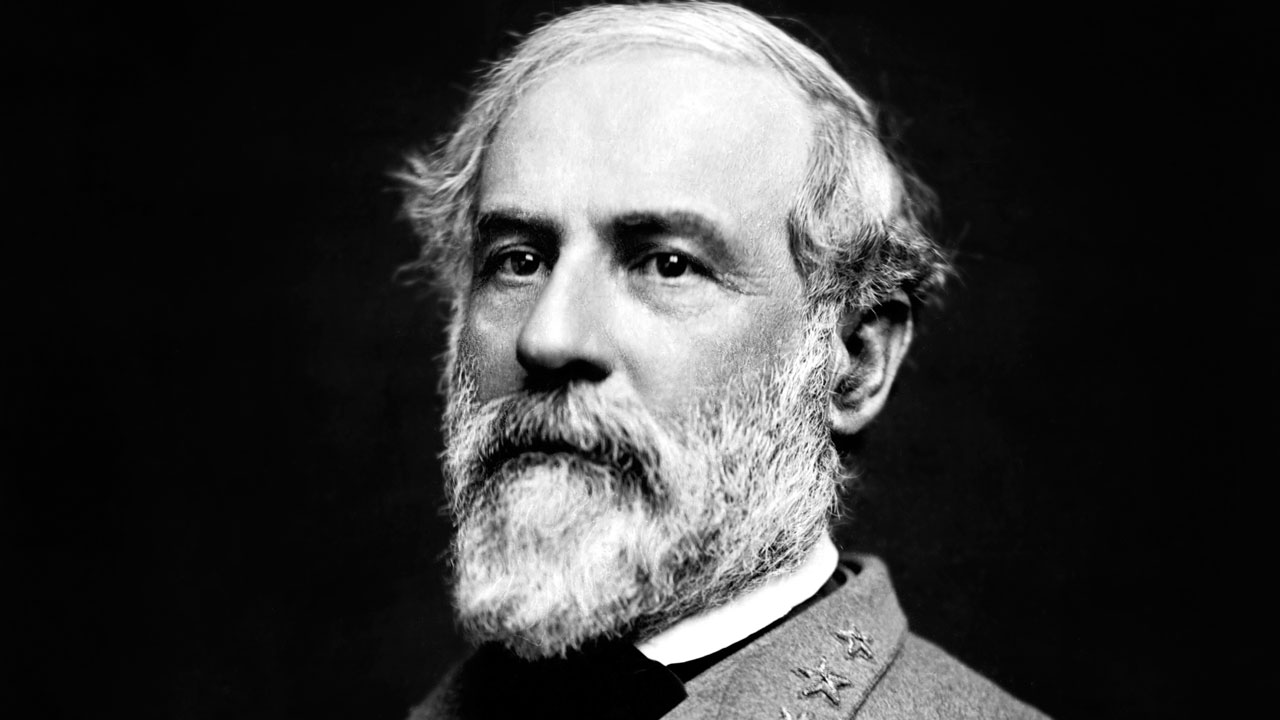

Robert E. Lee: Slave Owner, Slave Abuser, Confederate General And Leader Of Violent War To Maintain White Supremacy, Traitor

The statue of Robert E. Lee epitomizes the glorification and celebration of white supremacy and the elevation of false myths about the Civil War that romanticize the Confederacy and mute the horrors of slavery.

Lee was “loyal to slavery and disloyal to his country.” As a decades-long slave-owner who physically abused his slaves and used them as servants throughout the Civil War, Lee decided to leave his post with the United States Army in 1861 to become a leader of the cause of white supremacy. Lee chose to join the Confederacy despite the fact that many members of his own family supported the United States and honored their oaths of office to the military. Thus, pursuant to Article III, Section 3, Clause 1, of the U.S. Constitution, Lee engaged in treason against the United States. Far from being a revered figure, Robert E. Lee has been condemned for his “racist and dishonorable conduct” even by students of Washington and Lee University in Virginia, a school once presided over by Lee himself.

The Lee Monument was erected to propagate the Cult of the Lost Cause and its desire to remake the image of the Civil War as “a great heroic epic” wherein the South “waged a noble but doomed struggle to preserve their superior civilization.” Conceived between 1870 and 1876, when the trauma of defeat was still fresh in the South, a monument honoring “the most heroic and saintly of all Confederates, perhaps of all Americans . . .” was wholly consistent with the tenets of the Cult of the Lost Cause.

In the historical documents filed with the National Register of Historic Places regarding this statue, the record is clear that the Lee monument was constructed and honored as a central aspect of the Cult of the Lost Cause:

The Lee Monument is of regional significance in the cultural history of the South because it is a tangible symbol of the views of the majority of southerners during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In general, the monument represents what is known as the Cult of the Lost Cause. More particularly, it stands for a central aspect of the cult — the deification of General Robert E. Lee.

The National Register document concludes by saying:

In many ways Robert E. Lee was the centerpiece of the cult. He was arguably the most venerated Civil War figure in the South, and by the twentieth century had become a national hero. Indeed, he assumed an almost Christ-like stature. Monuments to Lee embody the highest aspirations of the Lost Cause cult. They, along with monuments to other southern Civil War figures, are the most tangible reminders of this extremely important and pervasive phenomenon.

Erecting statues to Robert E. Lee and others was part of the Lost Cause in all its myths, rituals, and symbols and helped Confederates deal with the trauma of defeat. These symbols of white supremacy helped reinstitute unity among ex-Confederates. Admiration of Lee and others was at the heart of the movement to reclaim mythologized glories and power.

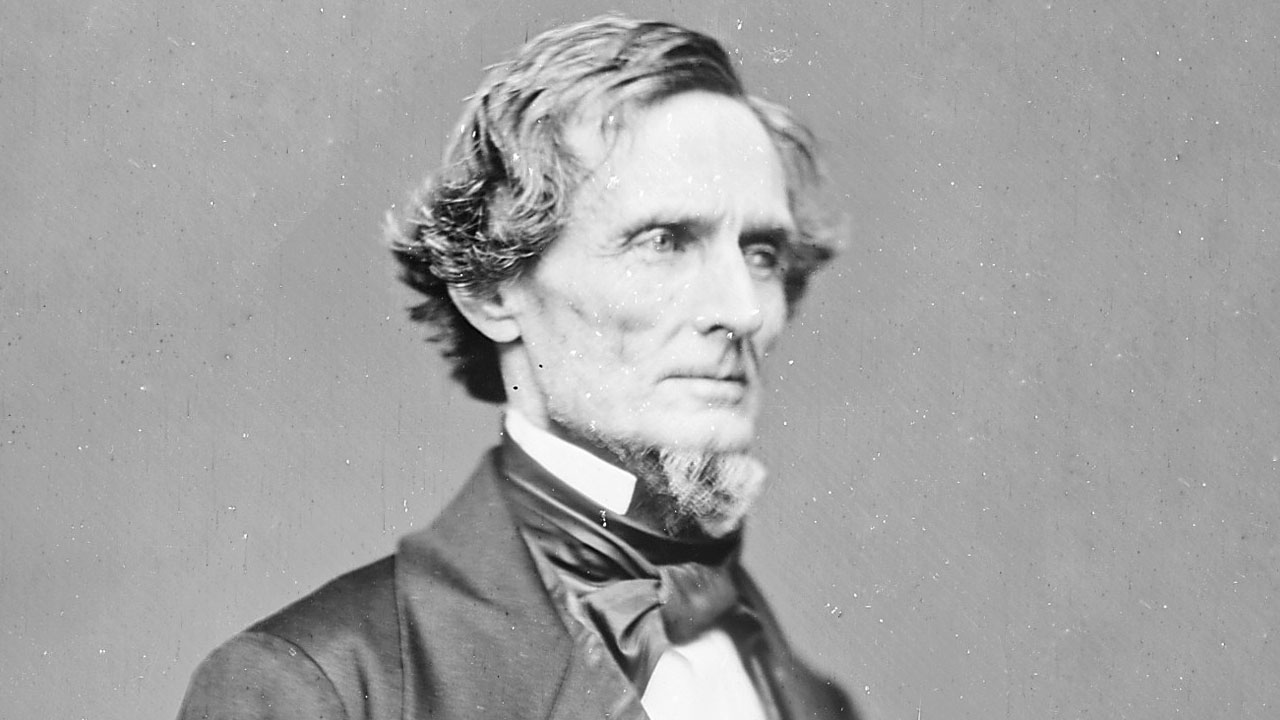

Jefferson Davis: Slave Owner, Racist, President Of The Confederacy, Traitor

Jefferson Davis was a slave-owning racist and traitor who led an unsuccessful insurrection against the United States. He is quoted as saying, “African slavery, as it exists in the United States, is a moral, a social, and a political blessing.” According to Davis, “its origin was Divine decree,” and the slave trade had been a blessing for the African, bringing him out of ignorance and degradation to a land of Christian enlightenment where the slave “entered the temple of civilization.” It was all by divine ordination that the black man had been made “a servant of servants.” Davis was also adamant that white supremacy over African Americans was key to the identity and place of white people:

You too know, that among us, white men have an equality resulting from a presence of a lower caste, which cannot exist where white men fill the position here occupied by the servile race. The mechanic who comes among us, employing the less intellectual labor of the African, takes the position which only a master- workman occupies where all the mechanics are white, and therefore it is that our mechanics hold their position of absolute equality among us.

Davis owned dozens of slaves, and as a U.S. Senator, he was an ardent defender of slavery and the rights of southern states to allow it. Davis argued in Congress that the Missouri Compromise threatened to take away his constitutional right as a slave owner to move about the country with his property.

Davis was elected president of the Confederate states on February 8, 1861. Under Article III, Section 3, Clause 1, of the U.S. Constitution, Davis engaged in treason against the United States. Davis defended slavery as a moral and social good, and he fought a monstrous war to maintain it.

His writings demonstrate that he remained racist and pro-slavery to the end of his life. Davis, like Robert E. Lee, became a hero of the Lost Cause in the post-Civil War south. To further demonstrate the nefarious purpose of this statue, one must only look at the fact that, as Plaintiffs themselves point out, the Davis monument association was organized in 1898, immediately after the disenfranchisement of African American voters, and was erected on the fiftieth anniversary of Davis’ inauguration as president of the Confederacy. From its inception, the monument was intended to broadcast white opposition to the advancement of rights for African Americans.

P.G.T. Beauregard: Confederate General, Slave Owner, Deserter, Traitor

P.G.T. Beauregard, born in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, was the Confederacy’s first hero when he presided over the surrender of United States troops at Fort Sumter. He is probably best known as the designer of the Confederate flag, the Southern Cross, in 1861.

Under Article III, Section 3, Clause 1, of the U.S. Constitution, Beauregard engaged in treason against the United States. After the war, Beauregard asked for a pardon, but only after writing Robert E. Lee and complaining “it is hard to ask pardon of an adversary you despise.” He subsequently signed a loyalty oath to the U.S. to retain his citizenship and make sure he was not prosecuted or charged with deserting his post at West Point.

Beauregard’s family owned slaves and he rented slaves to serve him during his time in the military. Though he later was an advocate for equal rights, his monument honors him as a Confederate general. The monument, completed and dedicated in 1915, bears the inscription “GT Beauregard, 1818-1893, General CSA 1861-1865.”

Documents filed with the National Register of Historic Places Database indicate that the statue is another of three Louisiana monuments to the Cult of the Lost Cause:

The General Beauregard Equestrian Statue is of statewide cultural significance as one of three major Louisiana monuments representing what is known by historians as the Cult of the Lost Cause. The other two statues, both also located in New Orleans, depict Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. Statues of this type are tangible symbols of a state of mind which was powerful and pervasive throughout the South well into the twentieth century (and some would say even today).

The National Register further states, “the deification of Southern heroes such as Beauregard and Robert E. Lee has continued to the present.”

When the Beauregard statue was dedicated, the glorification of Beauregard’s white supremacist past was exemplified by the following remarks from Judge John St. Paul: “Well, indeed, may they worship at his shrine, for he was one, and not the least, of that galaxy of heroic men whose glorious deeds have placed their age and the struggle in which they took part among the grandest that adorn the annals of all times.” As these remarks illustrate, the Beauregard statue lionizes one of the main champions of the Confederacy.

“Liberty” Monument: Violent Terrorist Resistance To Integrated Government

The so-called Liberty Monument honors the violent post-Civil War White League, a Louisiana white supremacist paramilitary terrorist organization. The White League, closely connected to the Ku Klux Klan, was the military arm of the Lost Cause movement in Louisiana which sought to reverse the loss of white supremacy. As eminent historian Eric Foner explains: “[t]he White League was formed with the avowed purpose of restoring white supremacy, by violent means if necessary.” The White League spread terror and assassinations across Louisiana before attempting to overthrow the lawful government of New Orleans in September 1874 by murdering New Orleans police officers and seizing government buildings.

The Louisiana White League emerged as “one of the most brutal white supremacist organizations in all of Reconstruction,” assassinating officeholders in Ouachita, Red River, Caddo, Natchitoches, and East Baton Rouge Parishes and engaging in several massacres across Louisiana. In April 1873, the illegal white militia attacked and murdered a hundred black Louisiana soldiers, half in cold blood after they had surrendered, in the Colfax Massacre in Grant Parish, Louisiana. Following another attack in Natchitoches, in August 1874, the White League murdered four blacks and six whites in the Coushatta Massacre in an attempt to overthrow the Republican government in northwest Louisiana. In 1875, U.S. General Philip Sheridan wrote a telegram to the U.S. Secretary of War describing the violence and terror of the White League: “I think the terrorism now existing in Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas could be entirely removed and confidence and fair dealing established by the arrest and control of the ringleaders of the armed White Leaguers.”

On September 14, 1874, in what has been called the Battle of Liberty Place, thousands of members of the Crescent City White League, including many Confederate veterans, challenged Louisiana’s integrated Reconstruction government by attacking and killing New Orleans police officers and inflicting 100 casualties. They captured the statehouse, the armory, and downtown New Orleans for days until retreating in the face of newly arrived federal troops.

The Liberty Monument was erected in 1891 to commemorate the Battle of Liberty Place and honor the members of the White League who murdered police officers and took over the City of New Orleans all in an attempt to undo the effects of the Civil War. At this time, the White League was so powerful that it had a member on the U.S. Supreme Court, and in 1891 veterans of the White League Liberty Place battle openly lynched eleven Sicilian men and used the lynching as a way to raise money to build the monument.

The Monuments Have Kept Alive The Confederacy’s Legacy Of Racial Oppression

Far from inert structures honoring a dead past, the monuments at issue have continuously served as a rallying point in efforts to entrench white political power and reaffirm the values of white supremacy. For example, in 1896, former members of the White League and young members of the city’s white elite staged mass rallies at the Liberty monument, repeatedly invoking the memory of the men who had fought there. Three days later, they led a procession that began at Lee Circle and ended at Liberty Monument. This show of power succeeded in pressuring local political representatives to negotiate with White League leaders, eventually allowing for the election of Walter Flower, the son of a White League veteran, as mayor. Additionally, in 1904, there were further rallies at the Liberty Place Monument to replace nominating conventions with a “white primary” that would have allowed only white voters to participate.

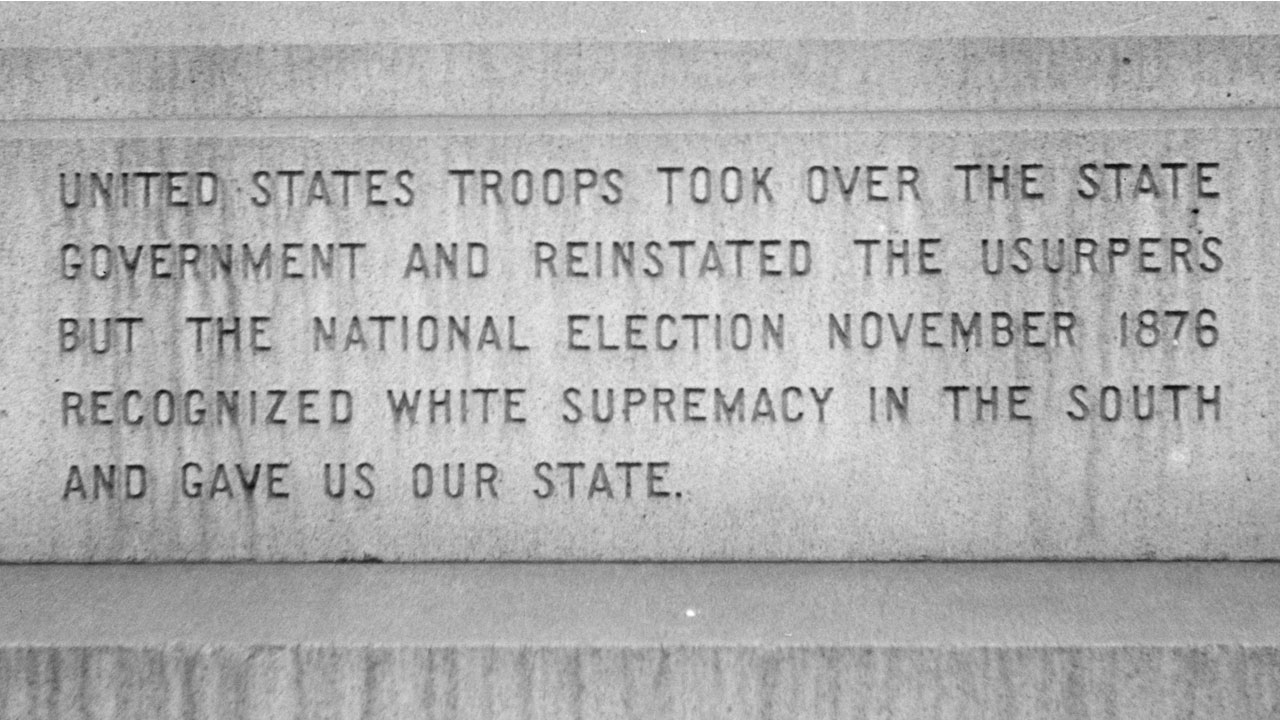

In 1932, a new inscription was added to the monument which read: “United States troops took over the state government and reinstated the usurpers but the national election in November 1876 recognized white supremacy and gave us our state.”

As one historian has noted, “[a]s rhetoric, the September Fourteenth tradition persisted well into the latter half of the twentieth century.” Celebrations of the monument grew particularly fervent during the civil rights movement. For example, in 1948, a large group of arch-segregationists gathered at the monument on the battle’s anniversary, and Congressman Eddie Herbert stated, “[i]t is one of history’s tragedies that we are gathered here at a time when the ideals for which the men of 1874 fought are being viciously attacked again on all fronts,” and exhorted that “the struggle for home rule must be won again.”

In 1955, a year after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education to desegregate public schools, a book entitled The Battle of Liberty Place, written by Stuart Landry and funded by many prominent white families in New Orleans, was published, characterizing the terrorism of 1874 as one of the highest achievements of the white race. Dedicated to “The Memory of the Heroes of the Fourteenth of September, whose Patriotism should be an Inspiration, not only to their Descendants, but to all Louisianans of Good Intent,” the book justified the organization of the Ku Klux Klan and other secret societies as a legitimate way to protect the rights of white people against the “carpetbaggers, scalawags, ignorant freedmen and rascally Southerners who joined in with these others to direct and control the newly enfranchised colored people for plunder and power.”

More recently, in the early 1990s, the monument became a rallying point for the Ku Klux Klan and David Duke when one of Duke’s supporters sued the City of New Orleans to restore the monument after it had been removed and placed in storage due to street repairs.

The Lee monument has also provided a site for white supremacists to celebrate their cause well into the twentieth century. In 1922, a poem published in the Times-Picayune sang the statue’s praises, reading: “He stands calm and firm. . . / watching with prophetic eyes / His beloved Southland: seeing in her / Cleaner American stock the saving strain / Which yet will right the balance / ‘Twixt conflicting alien hordes / And hold straight the course / Of America’s Ship of State / Toward the ultimate goal / Of a homogenous people. . . .” In 1972, several prominent Louisiana segregationists, including Addison Roswell Thompson, who had previously run for state governor and mayor of New Orleans, celebrated Lee’s birthday by draping a Confederate flag at the foot of the monument and setting out their Klan robes. The incident escalated into a racial confrontation with several black passersby. David Duke was among those jailed for “inciting to riot.”

These episodes show that by designating multiple places throughout New Orleans to publicly honor those that championed racism and oppression, the monuments have and continue to perpetuate belief, support, and pride in the Confederacy’s “Lost Cause,” and its vision of white supremacy.

Plaintiff Sons Of Confederacy Beauregard Camp No. 130

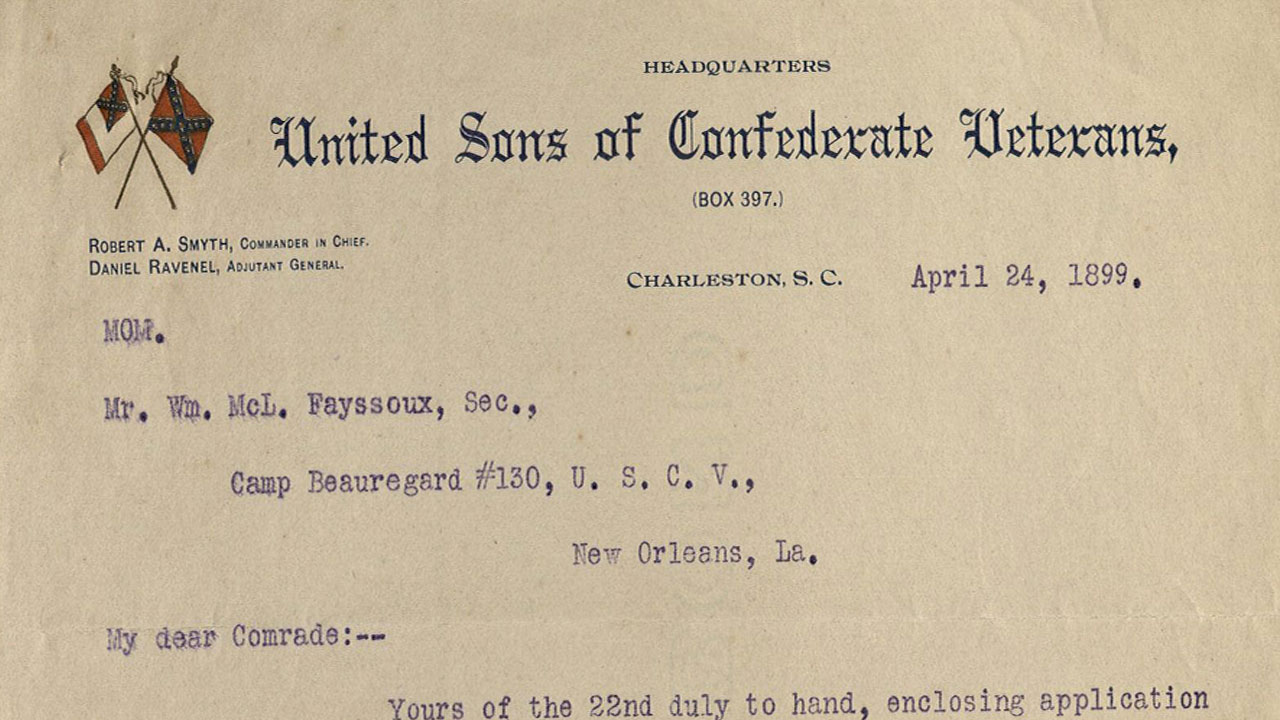

If there is any more need to prove that this matter is about preservation of white supremacy, the Court should take note that Beauregard Camp No. 130, Inc. is a named plaintiff in this case.

Plaintiff is a chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, which describes the Civil War as an honorable fight for liberty and freedom to such an extent that they call it the Second American Revolution.

In the complaint, Beauregard Camp describes itself as “an autonomous, local chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans,” and was “chartered in 1899 to preserve the memory and good name of General P.G.T. Beauregard, General Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and all Confederate veterans and elected civil servants who served honorably in the Civil War.” Plaintiff admits it played an active leading role in creating, funding, and erecting the Beauregard and Jefferson Davis monuments.

The Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) is a membership-based organization consisting of local chapters called “camps” that are located across the country. The group valorizes the service of Confederate veterans and their cause, writing that they “personified the best qualities of America” and that the “[t]he preservation of liberty and freedom was the motivating factor in the South’s decision to fight the Second American Revolution.” Founded in 1896 in Richmond, Virginia, the SCV reports that it has approximately 30,000 members. There are over thirty camps in Louisiana. Membership is open to any male who can provide documentation proving he is a descendant of a Confederate soldier or sailor.

The SCV states publicly that it has a “strictly enforced ‘hate’ policy” which requires that anyone with ties to any racist organization or hate group must be denied membership or immediately expelled. Prohibited organizations include the Ku Klux Klan, American Nazi Party, the National Alliance, or any organization expressing racist ideals or violent overthrow of the United States government.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (“SPLC”), however, in the past fifteen years the SCV has been riven by an “internal civil war” which continues to this day between those espousing racist beliefs (many of whom are closely aligned with white supremacist groups and individuals) and “history clubbers” whose primary interest is preserving and celebrating the history of the Confederacy.

For instance, Kirk Lyons is an active and prominent member of the SCV, holding a leadership position in the SCV’s youth camp and recently represented the organization in a failed lawsuit to prevent the removal of a statue of Jefferson Davis from the campus of the University of Texas. Mr. Lyons is also the chief trial counsel for the Southern Legal Resource Center, a pro-Confederate organization that he and his brother-in-law founded in 1996 that has defended the flying of the Confederate flag in a number of court disputes. Lyons previously defended a former Klan leader and the leader of an anti-Semitic group called Posse Comitatus, in addition to having been married in an Aryan Nation compound. Lyons has led efforts to turn SCV towards extreme-right political activism. The SPLC reports that in 2000 he stated alongside former Klan leader David Duke that the SCV needed to get rid of its “Grannies” and “bed- wetters” and said: “[t]he civil rights movement I am trying to form seeks a revolution. . . . We seek nothing more than a return to a godly, stable, tradition-based society with no ‘Northernisms’ attached, a hierarchical society, a majority European-derived country.”

Another such extremist is Ron G. Wilson, who was elected in 2002 to serve as SCV’s commander in chief—the group’s highest office. During his two years in office, Wilson suspended around 300 members for publicly criticizing racism within the group. Many of these members had been associated with an anti-racist offshoot of the SCV, called Save the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Wilson appointed Lyons to the SCV’s Long-Range Planning Committee. His election set off a struggle over the SCV that has reportedly led to the loss of thousands of its more moderate members.

In 2004, Denne Sweeney took over as national leader and continued Wilson’s policies and also permanently expelled the 300 men suspended by Wilson. Sweeney implemented measures that favored the influence of radical elements of the SCV. After Sweeney prevailed over moderates who challenged his decisions in a lawsuit, the rift between radical and moderate members of the SCV deepened, and some former members started new groups meant to be non- racist history clubs.

Despite its official rejection of overtly racist ideology, the group’s work and the legacy it seeks to preserve is deeply intertwined with white supremacy. To illustrate this point, in 2000, the SVC’s Selma, Alabama, chapter erected a monument to noted KKK member and Confederate general, Nathan Bedford Forrest. The monument is located in a large cemetery in Selma—a site that is deeply significant in the Civil Rights Movement—in a part of the cemetery dedicated to Confederate soldiers. A picture of the monument is available online.

After the shooting of unarmed African Americans in Charleston, the group issued a public statement condemning the act and decrying racism (while also accusing its “politically correct opponents” of attempting to politicize the tragedy). However, despite these initial statements, the SCV has played a prominent role in organizing other pro-Confederate flag movements in the wake of the Charleston killings.

Although the Sons of Confederate Veterans has disavowed racism in its official pronouncements in recent years, the group is still deeply invested in elevating and legitimizing its version of the Confederacy’s “history” and “traditions,” which implicate an inherently racist, white supremacist vision of society.

This plaintiff is a living current example of the Cult of the Lost Cause and the glorification of the violent racist Civil War which was fought to preserve the enslavement of millions of African Americans. They call the Civil War the “Second American Revolution” and praise as honorable the people who committed treason.

The fact that the plaintiff in this case is a chapter of the SCV demonstrates why the City of New Orleans not only has the right to take down these statues, but why they must.

Conclusion

The statues at issue in this case honor and glorify treasonous white supremacists who would likely be charged as terrorists today. Their violent actions supported white supremacy and the continued enslavement of millions of people. The monuments erected in their “honor” were constructed and maintained in a deliberate effort to perpetuate historical myths of southern glory when black people were property to be used and abused. By enshrining a patently false version of history, the monuments have helped keep these myths and the oppression they justify alive.

These statutes fit exactly into Section 146-611 (b) of the New Orleans Code of Ordinances which authorizes the City Council to remove statues from public property when those statues are a nuisance:

The thing honors, praises, or fosters ideologies which are in conflict with the requirements of equal protection for citizens as provided by the constitution and laws of the United States, the state, or the laws of the city and gives honor or praise to those who participated in the killing of public employees of the city or the state or suggests the supremacy of one ethnic, religious, or racial group over any other, or gives honor or praise to any violent actions taken wrongfully against citizens of the city to promote ethnic, religious or racial superiority of any group.

The monuments foster ideologies which are in direct conflict with the requirements of equal protection of our citizens. They honor the killing of public employees. And they honor and praise violent actions that were taken to promote white supremacy, the racial superiority of a group of whites who fought our nation’s most violent and bloody war.

Not only can the City of New Orleans remove these statues, it must.

For a full listing of footnotes and references please see the amicus brief (PDF) as it was filed.