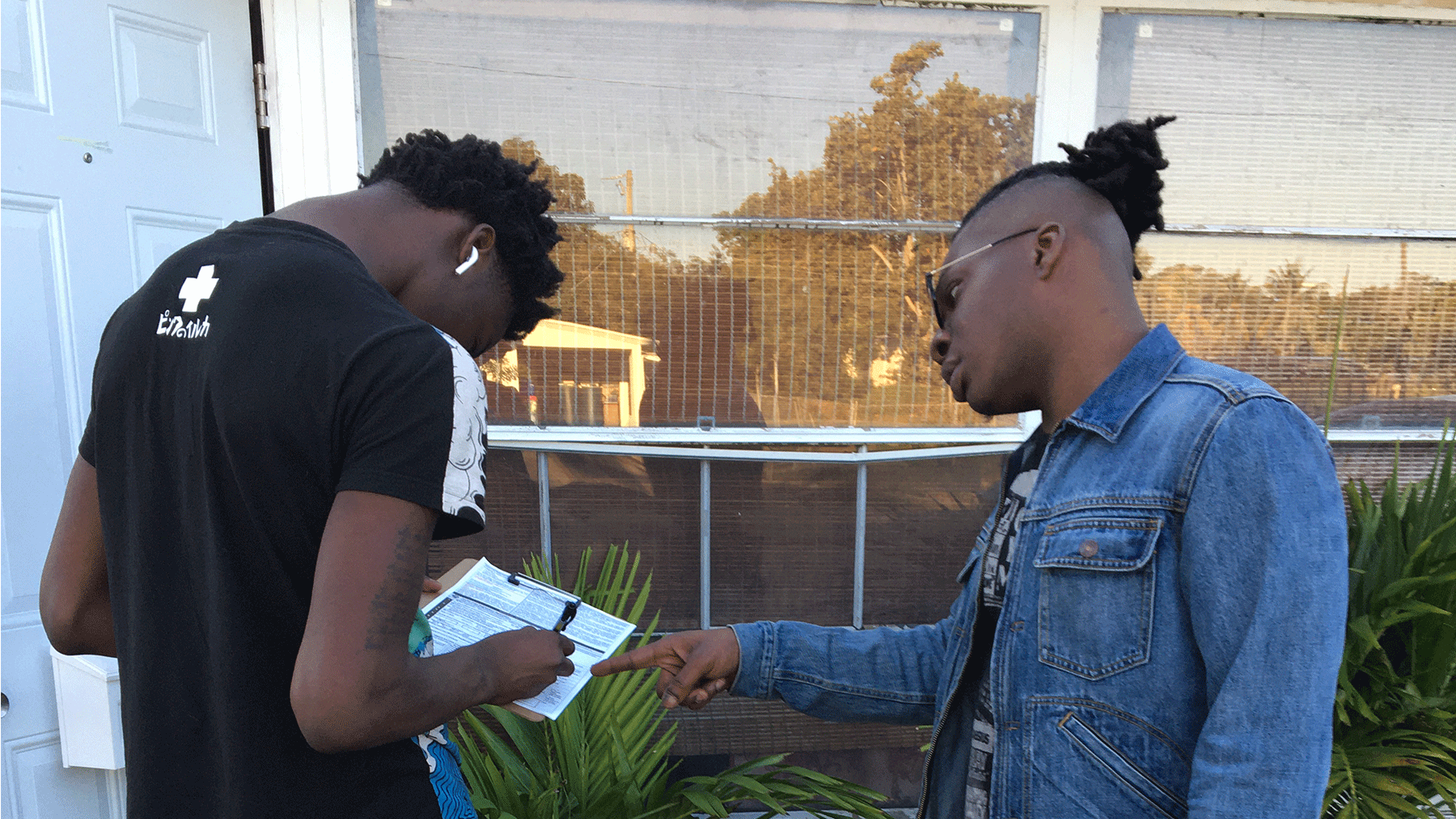

Clutching a clipboard full of voter registration forms under his arm, Marq Mitchell knocked on the front door of a small, beige, stucco house in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

As palm trees swayed in the front yard, the reddish-brown door of the house creaked open, and a short, Black woman greeted him.

“Good afternoon, how are you?” Mitchell asked. “We’re just out to make sure that everyone is registered to vote. Are you registered to vote?”

“No,” she told him. “I have a background problem. So I cannot.”

Mitchell answered: “You have a background problem where you’re not eligible to vote? Are you aware that Amendment 4 passed last year where people with felonies are now eligible to vote?”

Mitchell and his small crew of vote canvassers – including partners from other local grassroots organizations – had similar conversations with over 7,000 people over the last month and a half.

The conversations that people on Mitchell’s staff had with thousands of potential voters formed the backbone of an SPLC-sponsored effort, “Raise Our Vote,” to identify and register people in Broward and Miami-Dade counties in South Florida who have previous felony convictions and whose rights have been restored under Amendment 4.

In November 2018, Florida voters overwhelmingly approved Amendment 4 to restore the right to vote to 1.4 million of their fellow residents with previous felony convictions. It was the largest single expansion of voting rights since the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But that victory was quickly undermined by Florida lawmakers and Gov. Ron DeSantis, who put into place what amounts to a modern-day poll tax. The new law passed in the wake of Amendment 4 meant that hundreds of thousands of newly enfranchised people still couldn’t vote because of the legal debt they owed – such as fines, fees and court costs – but couldn’t afford to pay.

A February ruling by a judge meant that the SPLC’s plaintiffs who have served their time for felony convictions are now able to cast ballots along with their friends and neighbors.

The SPLC is continuing to fight so that hundreds of thousands of others who have legal financial obligations also will be able to cast their ballots. During a trial later this year, the SPLC plans to enter additional evidence establishing that this voter-suppression law is unconstitutional.

“Felon disenfranchisement laws that disproportionately impact poor people and people of color remain a serious barrier to those wishing to exercise their fundamental right to vote,” said Nancy Abudu, SPLC deputy legal director for voting rights. “The longer-term impact is that those most impacted by terrible policies that perpetuate cycles of poverty are left completely voiceless in the political process. Therefore, we will continue to challenge election laws that exclude the most vulnerable members of our society.”

Mitchell’s month-and-a-half-long effort, stretching from February to mid-March, collected nearly 700 voter registration forms. Of the nearly 500 new voters that the effort successfully registered, over 300 were able to register to vote because of Amendment 4. These hundreds of new voters were registered just in time for the Florida primary elections this week.

‘I have felonies, too’

Mitchell is the founder of Chainless Change, a nonprofit that advocates for individuals and families who are negatively impacted by the criminal justice system. He served two months in Miami-Dade County Jail in 2011 for battery on a law enforcement officer, stemming from a fight with a campus security guard while he was a student at Florida Memorial University in Miami Gardens.

His criminal record meant that he was no longer eligible to vote – until Amendment 4 passed.

He registered to vote for the first time last March in Broward County and got his voting card in the mail. But then he got a letter from the Miami-Dade County clerk telling him he still owed court fees and would be removed from the voter rolls until they were paid.

“I have felonies, too,” Mitchell told one voter who had been incarcerated. “And it’s very important for me to vote because I understand that it’ll change everything.”

Mitchell said it was particularly important to vote in Florida because recent elections there were decided by very small margins. He added it is important to vote for people who would support the rights of people who are returning to their lives after serving jail or prison time.

While canvassing in Fort Lauderdale, Mitchell started a conversation with Walter Atwell, who said he was not interested in voting because he was ineligible due to a nonviolent felony conviction for drug sales.

Under Amendment 4, however, he is now eligible to vote.

Working under the hood of his red Ford SUV as rap music pumped out of a nearby speaker, Atwell said that he feels alienated from the process because of his criminal record.

“I ain’t never voted a day in my life,” Atwell said, adding that a clean record – not a ballot – would allow him to get better jobs.

Ironically, he said, he currently drives a truck for a government agency that oversees elections.

Mitchell explained that getting back the right to vote could help Atwell in other ways, too.

“Because you’ll be able to vote for people who will support you having your rights,” Mitchell said. “There’s a lot of criminal justice bills that were discussed during this legislative session and they didn’t get passed because we didn’t have enough support in the state. The way that we get that support is voting those people up into office.”

‘My vote will help the neighborhood’

In the months leading up to the November election, the SPLC will continue to work with communities to help people to register, restore their right to vote, and cast their ballots.

Evelyn Blanco needed no encouragement about her right to vote in Miami Gardens.

When the canvassers approached her, she said she planned to vote for someone in the local election who has her neighborhood’s best interest at heart. For her, that means fixing up the park near her house where people have illegally dumped trash.

“I want the neighborhood to be safe,” she said. “My vote will help the neighborhood to get much better, especially in that park.”

Photos by Brad Bennett