When the Southern Poverty Law Center goes to trial on Monday (April 27) over a law undercutting the biggest expansion of suffrage since the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the judge will not be on the bench, but in a remote location, staring at his computer screen.

Lawyers on both sides of the case will be sitting at home, making their arguments, cross-examining witnesses, conferring with clients, making objections and presenting evidence – all without seeing each other in person.

With almost everyone encouraged or ordered to stay home or keep a safe distance of at least six feet from other people to avoid spreading the coronavirus, the trial is not allowed to take place in a physical courtroom of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida. So the “courtroom” will be online.

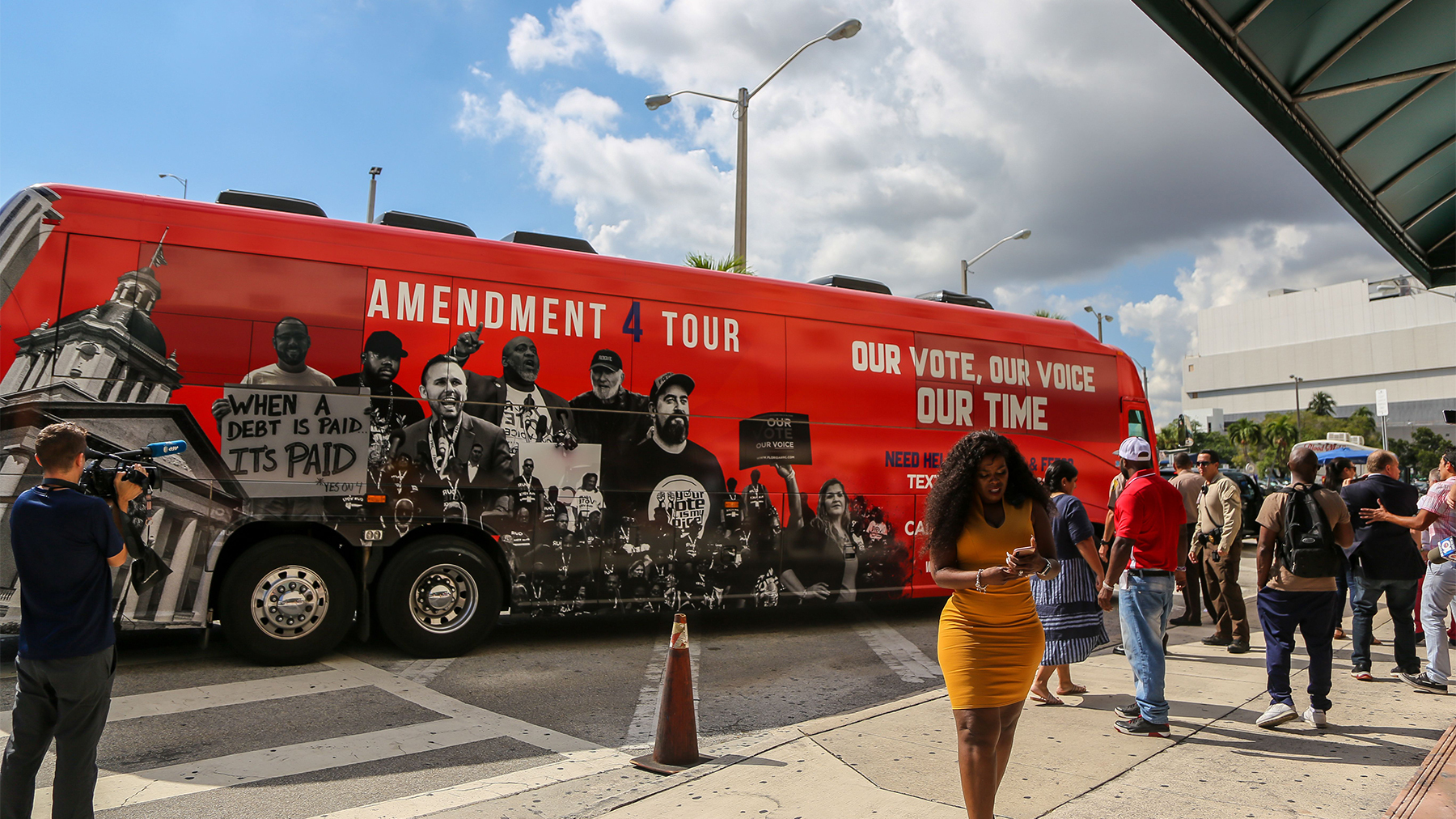

The SPLC Voting Rights Practice Group and a coalition of partners are supporting Amendment 4, a measure that Florida voters overwhelmingly approved to restore the right to vote to 1.4 million Florida residents with previous felony convictions. Soon after it was passed, Amendment 4 was undermined by a new law, SB 7066, that created a modern-day poll tax.

The SPLC will argue that the law – which requires people who have completed their sentences for felony offenses to pay their fines, fees and restitution in full before they can vote – is unconstitutional.

“Floridians like our clients, Rosemary McCoy and Sheila Singleton, are unable to overcome the financial barrier to voting that SB 7066 presents – potentially for the remainder of their lives,” said Nancy Abudu, director of the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group. “A person’s lifetime participation in our democratic process cannot and should not be conditioned on their wealth. We will argue and emphasize to the court the very real and serious burden this law places on our clients and others in their situation.”

‘Courts are going digital’

The proceedings will take place primarily on a video conferencing application that allows multiple people to talk to each other on their computers.

“To our knowledge, this is the first voting rights case to go to trial virtually,” said Caren Short, senior staff attorney for the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group. “This is all because of COVID-19. All the courts are going digital.”

The people participating in the online trial will be spread along most of the East Coast and even as far away as the Midwest. Those who are directly involved in the trial will be allowed into the virtual courtroom by way of a closely guarded link that is password-protected to prevent what’s known as “Zoombombing,” when uninvited attendees break into and disrupt a video meeting.

But anyone from the public can listen in on the trial by phone via a special number that will be posted on the court’s docket. The phone conference will be like a gallery – where members of the general public are allowed to sit behind the lawyers in a traditional courtroom – except that there will be a lot more “room” for people to participate.

Some normal court activities will be different in the virtual world.

Everyone except the person presenting their case or presenting evidence at the time will have their video turned off. If a lawyer wants to object to something, they have to turn on their video and hope that the judge notices so they can make their case. Evidence will be presented via screen sharing.

Over the last few weeks, the SPLC’s voting rights legal team has been practicing on the video system with each other and their clients to troubleshoot any issues before trial.

“We’ve been working with the court’s IT personnel to test it out,” Short said. “They gave us some tips on which browsers to use and how to work it and the best way to proceed.”

There are also other challenges in a video courtroom.

“We’re not physically present with our clients or our witnesses,” Short said. “So they’re going to be by themselves testifying. We’re not even in the same state. It’s just sort of a whole new world where we’re not able to prepare for the testimony in the same room. It’s not just the trial itself. It’s all the things leading up to it.”

The prospect of testifying online hasn’t dampened the spirit of McCoy, one of the plaintiffs.

“We worked so hard to get the support of 5.1 million voters across the state to pass Amendment 4 in 2018,” she said. “I am excited to tell my story to the court … so that thousands of people just like me can finally use our voices to improve our community.”

Singleton is also looking forward to the trial.

“I’m excited to finally have my day in court to make clear to the judge why my vote matters and that the amount of money in my bank account shouldn’t prevent me from having a voice in my community,” she said.

Fines, fees, court costs and restitution

At stake in the online trial are the voting rights that Amendment 4 restored, but that the new law undercuts.

In November 2018, Florida voters overwhelmingly approved Amendment 4 to restore the vote to 1.4 million of their fellow residents with previous felony convictions. It was the largest single expansion of voting rights since the civil rights movement.

That victory, however, was quickly undermined by Florida lawmakers and Gov. Ron DeSantis, who signed SB 7066, requiring hundreds of thousands of newly enfranchised people to pay off legal debt they owe – such as fines, fees, court costs and restitution – before they can vote.

However, last October, the district court temporarily blocked SB 7066 from going into effect, allowing the plaintiffs to cast their ballots in the March primary elections before the trial.

Now, the SPLC is collaborating with other civil rights organizations whose cases challenging Amendment 4 have been consolidated with the SPLC’s lawsuit and will be argued at the same time.

The other organizations in the coalition are the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the ACLU of Florida, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law, and the Campaign Legal Center. The cases that have been consolidated with the SPLC’s McCoy v. DeSantis lawsuit are Gruver v. Barton and Raysor v. Lee.

During the trial, the court will hear testimony from Singleton, one of the SPLC’s plaintiffs.

After being incarcerated for six months, Singleton came out owing money for fines, fees and restitution that she is still unable to pay. In February 2019, she received a voter registration card from the Duval County Supervisor of Elections office and voted in a countywide election.

But in May 2019, she was informed that she owed nearly $1,000 in court-ordered costs, fines and fees associated with her criminal sentence. The county clerk also informed her that she owed nearly $15,000 in victim restitution, plus any and all interest that continues to accrue on the principal amount. Currently, she owes over $16,000.

Because of her criminal history, it has been extremely difficult for her to find a job that allows her to pay her living expenses, let alone court-ordered debt.

‘Disproportionately impacted’

Singleton wasn’t the only person being disenfranchised by this modern-day poll tax. The SPLC’s other plaintiff, McCoy – and hundreds of thousands of otherwise newly enfranchised people – couldn’t vote because of legal financial obligations.

And while the October ruling in the SPLC’s lawsuit meant that Singleton and McCoy, who owes almost $8,000 in court-ordered debt, could cast their ballots, hundreds of thousands of other voters are still prevented from voting due to the modern-day poll tax.

“Because women of color enter and exit the criminal justice system at a financial disadvantage, SB 7066 especially endangers their ability to vote. We will continue to fight on behalf of our clients and all Floridians who have been unconstitutionally denied such a fundamental right,” Abudu said. “Whether it’s in a traditional courtroom or online, we won’t give up the legal fight to protect the equal rights of all people.”

Photo by Zak Bennett/Getty Images