Carla Duffy and Janet Savage waited nearly three hours in the hot sun outside the George Ford Center in Powder Springs, Georgia, to cast ballots in the state’s June 9 primary. Masked up to ward off the coronavirus, they were determined to vote despite lines that snaked down the street.

After about 90 minutes in line, voters at the predominately Black precinct were told the state’s new voting machines were not working. In a scene that played out across the state, they were given paper ballots. The ordeal left Duffy and Savage with little confidence in Georgia’s ability to conduct a fair election in November’s presidential contest. The primary, for example, was originally scheduled for May 19, but was pushed back due to concerns about the pandemic, a delay that appeared to have little effect on the state’s readiness once voters arrived at the polls.

“I’m very afraid,” Savage said of what may happen at Georgia polling places in November. “The experience [during the primary] and the fact that they were not prepared. I don’t know if the [poll worker] training was adequate and we did hear that some people did not show up because of the COVID-19 crisis. I am very, very afraid. Had the provisional ballots been ready to go I would have felt better.”

The pandemic and the typical partisanship divide on what constitutes a fair election have voters, advocates and others concerned what will happen at the polls this November. Republicans, including President Trump, often insist the absentee ballot process – which some advocates say must be widely available in November to ensure the pandemic doesn’t suppress voter turnout – is rife with fraud, despite failing to substantiate such claims.

Meanwhile, Democratic leaders in many states are accusing Republicans of using suppression tactics to prevent people of color from voting: voter roll purges, the closing of polling places at historically black colleges and universities, and the passage of voter ID laws that disproportionately affect low-income and Black and brown voters.

It’s a seemingly perfect storm for voter suppression that could potentially dim the election prospects of women and candidates of color, and has advocates motivated to increase turn out and ensure everyone’s vote is counted.

A Moral March on Washington

The Rev. Dr. William Barber leads Repairers of the Breach, an organization working to make sure the voices of low-income people are heard by politicians on all levels. Barber’s group embarked on a 25-state listening tour that culminated in a Mass Poor People’s Assembly and Moral March on Washington Digital Justice Gathering on Saturday, June 20.

The three-hour event included celebrities, experts and citizens sharing information and giving impassioned speeches about creating solutions to fight poverty and voter suppression, among other issues.

The virtual gathering has already garnered 2.5 million views on Facebook, and 300,000 letters have been sent to governors and members of Congress, said Martha Waggoner, director of communications for Repairers of the Breach.

Barber said it is imperative that people of all races form a coalition to fight for fair elections and other issues such as better wages, adding that voter suppression tactics don’t just impact communities of color – they affect people of all races, particularly the poor.

“We are working to build power and shift the narrative. When we took a hard look at the numbers there are 140 million poor and low-wealth people in this country; 66 million are white, 26 million are black. We also have a study coming out that’s going to show that if you were to register anywhere from 2 to 10% of poor and low-wealth people and organize them around an agenda, you could fundamentally shift the political calculus all over the country and especially in the South.”

Barber says 100 million people, however, didn’t vote in the 2016 presidential election. Many were low-income people who don’t believe their issues are ever addressed. That’s why Barber’s group has traveled to many places throughout the South – including the hills of Eastern Kentucky – to meet with low-propensity voters and explain how they are victims of political disenfranchisement and their vote is power.

If voting wasn’t important, notes Bakari Sellers, an attorney and CNN commentator, “they wouldn’t try so damn hard to take it from you.”

“It’s not as if it’s an original thought,” he says of voter suppression. “Most of these Republican-led initiatives come from [the American Legislative Exchange Council], a conservative think tank that is behind voter ID laws, limiting early voting and ensuring that voting is not a national holiday.”

Such tactics are especially prevalent in the South, “But we are starting to see it trickle up,” he said. “There was no greater threat to our democracy in terms of using voter suppression strategies than Scott Walker in Wisconsin.”

Walker, a former governor of Wisconsin, was accused of backing voting laws that suppress the vote. In 2016, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton lost Wisconsin by 30,000 votes.

“Many would say [Clinton] had to go to Wisconsin, and I don’t disagree with that,” Sellers said. “But we’re not talking some whopping defeat she took, we’re talking 30,000 votes.”

In Georgia, Stacey Abrams lost the 2018 gubernatorial race by less than 50,000 votes during an election where Abrams questioned whether all the absentee ballots were processed. Abrams has been an outspoken critic of an issue other politicians and voters in the state have raised for years: malfunctioning voting machines and the resulting long lines that seem to crop up more often in predominantly Black areas. Her opponent, Brian Kemp, oversaw the elections process as secretary of state. He did not recuse himself until the election results were formally contested.

Abrams has since launched Fair Fight, an organization which aims to ensure that every vote is counted. On CBS’ “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” she described the 2020 Georgia primary as “an unmitigated disaster,” noting that the secretary of state placed the responsibility for the polling problems at the feet of local officials.

“It depended on the county you lived in if you had access to democracy,” she said during the interview.

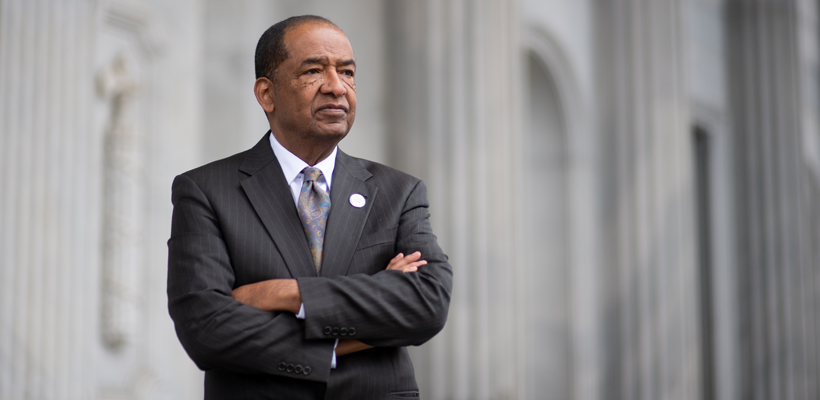

The Rev. Dr. William Barber

The Rev. Dr. William Barber leads Repairers of the Breach, an organization that works to ensure that low-income people are heard by politicians. Barber said registering and organizing 2% to 10% of low-income and low-wealth people “could fundamentally shift the political calculus all over the country and especially in the South.” Getty Images/CQ Roll Call/Tom Williams

Bakari Sellers

If voting wasn’t important, said Bakari Sellers, political analyst, attorney and CNN commentator, “they wouldn’t try so damn hard to take it from you.” Photo by Sean Rayford

Stacey Abrams

Former Georgia gubernatorial candidate, Stacey Abrams, is the founder of Fair Fight, an organization that seeks to protect voting rights. Abrams lost the 2018 gubernatorial race by less than 50,000 votes in an election where she questioned whether all the absentee ballots were processed. Getty Images/Jessica McGowan

Dr. Bernard LaFayette Jr.

Dr. Bernard LaFayette Jr. led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s voter registration efforts in 1963 and 1964 in Selma, Ala. The organization considered registering people to vote in Selma nearly impossible because “the white folks were too mean and the black folks were too scared,” recalls LaFayette, now a professor at Auburn University. Photo by Sydney Foster

Cleveland Sellers

Cleveland Sellers – father of Bakari Sellers – is one of the survivors of the Orangeburg Massacre, where highway patrolmen shot and killed three people who were protesting a whites-only policy at a bowling alley in Orangeburg, S.C., on Feb. 8, 1968. Sellers and 19 others were wounded in the melee. The protesters, mostly college students, were unarmed. Photo by Sean Rayford

Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed

“What we face today is nothing compared to what our foremothers and forefathers faced with literacy tests and poll taxes,” said Steven Reed, the first Black mayor of Montgomery, Ala. “We’ve seen this playbook before in our history, we just need to understand how to respond to it.” Photo by Cierra BrinsonShelby v. Holder

Perhaps the biggest blow to voting rights came in 2013, when the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Shelby County, Alabama, v. Holder, to dismantle Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The decision meant that states with histories of racial discrimination no longer were required to pre-clear changes in voting laws with the federal government before they take effect. Since then, a torrent of voting measures, such as voter ID laws, have fallen on communities of color in states that were once subjected to preclearance and some that were not.

For voting rights advocates, the situation underscored Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s dissenting opinion, which argued that “throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work … is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Since the Shelby v. Holder decision, voting rights activists have been working in the courts and in communities to encourage people to understand the need to educate themselves so they can be better prepared to counter voter suppression.

“Systemic racism and voter suppression are at a height we haven’t seen since Jim Crow,” Barber said. “We’ve had 26 states since 2010 pass voter suppression laws of various sorts. We know very clearly that every state that is a voter suppression state is a low-wealth state or a living-wage state.”

“The Voting Rights Act needs to be fully restored,” Barber said. “Ever since June 5, 2013, Congress could have fixed the Voting Rights Act. They have not fixed it and by not fixing it they continue to allow states like Alabama and Georgia and North Carolina – the legislatures – to pass these laws and have them be implemented while we have to fight them in the courts.”

A victory for voting rights

But it hasn’t been all bad news for voting rights.

The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida recently struck down provisions in Florida law SB 7066 that required people with felony convictions to pay off legal financial obligations before voting. The court held the law discriminates against those who lack a genuine ability to satisfy restitution and fines. What’s more, the court concluded that conditioning voting rights on the payment of court costs and fees constitutes an unconstitutional poll tax.

SB 7066 was quickly passed by the Legislature and signed into law by Gov. Ron DeSantis after voters overwhelmingly approved Amendment 4 in 2018. The amendment restored the vote to 1.4 million residents with previous felony convictions. It was the largest single expansion of voting rights since the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Felon disenfranchisement is a form of continuing punishment, said Nancy Abudu, who heads the Southern Poverty Law Center’s voting rights practice group, which was among those bringing litigation challenging SB 7066. “Just because you lose your right to vote doesn’t mean you are stripped of all constitutional protections. Requiring people to pay money [in the way of fines, victim restitution and court costs] that they don’t have to vote is totally irrational.”

She also highlighted how it affects women and, particularly, Black women.

“You talk about women who already statistically make less money than men and our numbers are statistically high compared to men,” she said. “We come out of prison and simply don’t have the same access to employment opportunities that men do. Usually the work is seasonal or part time and it’s not a living wage. Couple that with the intersection of race and there’s a significant gap in pay. Almost 44% of Black women with a felony conviction are unemployed.”

The past is prologue

When it comes to today’s voting rights issues, some civil rights activists of the 1960s see the strategies of the past as key.

Dr. Bernard LaFayette Jr. frequently talks with people who are apathetic about voting. Instead of reminding them that people like him nearly died for the right to vote, he tries to appeal to them from the standpoint of improving their lives. They need to see what’s in it for them, said LaFayette, who led Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign in 1968.

LaFayette also led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s voter registration efforts in 1963 and 1964 in Selma, Alabama. The organization considered registering people to vote in Selma nearly impossible because “the white folks were too mean and the black folks were too scared,” recalls LaFayette, now a professor at Auburn University.

Cleveland Sellers, Bakari Sellers’ father, and other SNCC activists who registered people to vote in Mississippi in the late 1960s, said “people had to be willing to put their lives on the line. They had to understand the importance of organization and empowerment of people who had been undermined and, in some cases, in communities actually destroyed.”

“Dr. King often talked about the beloved community, community on the hill,” Cleveland Sellers said. “It was multiracial, it was inclusive, and it also allowed for other differences for people to come together over having that control and that control is simply in the vote.”

The elder Sellers is a survivor of the Orangeburg Massacre in South Carolina, where 200 unarmed college students were shot by highway patrolmen while demonstrating against a whites-only policy at a bowling alley on Feb. 8, 1968. Three people were killed.

Sellers, however, was the only person charged in the melee. He was convicted of rioting and spent a year in jail. In 1993, 25 years after the massacre, he received a full pardon from the state of South Carolina. He went on to become director of the African-American Studies Department at the University of South Carolina, and later, president of Voorhees College in Denmark, South Carolina.

The next generation of progressive leaders – such as Mayor Jacob Frey of Minneapolis, and Steven Reed of Montgomery, Alabama – are carrying the elder Sellers’ work forward.

While people were excited to see him elected as the city’s first Black mayor, citizens want to see results, said Reed. “They want to see opportunity. I don’t mind them having those type of expectations, they are not higher than the ones I place on myself,” he said.

Reed said there will always be people opposed to progress made by women and people of color. Challenges to the Voting Rights Act are to be expected as some people feel threatened by those gains.

“It was manifest by the voting rights laws that were carried out by the secretaries of states. It’s important to understand how our government works,” Reed said. “[Voter suppression] doesn’t just happen at the congressional level. It happens through Shelby v. Holder that helped remove preclearance. It happens at the judicial level. Then you come down to the state level where they are moving precincts off college campuses and where they are purging voter rolls.”

Citizens must stay engaged and aware of the strategies being used to keep people away from the ballot box, he added. “We have to be sure that despite those obstacles that might be placed in our way that we are willing to persevere and that we are courageous enough to fight back. That means, organizing, that means engaging. And that means pushing things on the national, state and local level – all the way through.”

“What we face today is nothing compared to what our foremothers and forefathers faced with literacy tests and poll taxes,” Reed continued. “We’ve seen this playbook before in our history. We just need to understand how to respond to it.”

As for Carla Duffy who took part in Georgia’s primary with her 18-year-old daughter Jasmine, a first-time voter, the duo didn’t let the long lines and malfunctioning voting machines dampen their enthusiasm.

Said Carla Duffy: “I vote because I want to make a difference by supporting those men and women who step up to the plate to serve on everyone’s behalf. I also vote to serve as a role model for my daughters.”

Lead photo by AP Images / Brynn Anderson

Angela Tuck is a senior editor with SPLC’s Intelligence Project. For more information on the SPLC’s work on voter rights, go to: www.splcenter.org