Center Street in New Iberia, Louisiana, has seen better days. Once the main highway into town from neighboring Abbeville, it begins at Main Street near the Shadows-on-the-Teche plantation and stretches west, forming the edge of the city’s business district before passing in front of the former New Iberia High School, which now serves as senior living apartments and an after-school program site.

Tucked away behind the Classic Revival-style brick school is Lloyd G. Porter Memorial Stadium. Decommissioned in 2014, it still stands ready, the grass and building maintained for occasional use in case newer facilities become flooded or otherwise unavailable. Built in 1939, the stadium is named after the longtime Iberia Parish Schools superintendent during whose tenure it was built.

But the fact that the facility still bears Porter’s name is a problem for many in the Black community because of the role Porter played in the expulsion of Black physicians and leaders from the city in 1944.

As with many memorials, such as those honoring Confederate generals, politicians and others known for their role in the “Lost Cause,” the actions of people memorialized in towns such as New Iberia sometimes tarnish quickly in the light of history.

“I’m not as concerned about former plantation owners as I am about the 20th century segregationists of this community who terrorized New Iberia’s Black citizens for demanding the same opportunities as white citizens,” said Phebe Hayes, a retired professor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and founder of the Iberia African American Historical Society. “Black men were actually beaten and murdered in Iberia Parish for exercising the right to vote and demanding access to better jobs and education. In so many former Jim Crow towns like ours, the perpetrators of such violence are honored to this day with streets and public buildings bearing their names.”

“This shouldn’t be a complicated process,” said Tafeni English, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Civil Rights Memorial Center in Montgomery, Alabama. “Buildings, streets, schools or other public spaces should not be named after people who had a role in perpetuating violence on communities of color. The work we do at the Civil Rights Memorial Center is not only to educate and deepen the understanding of the past civil rights movement, but it also aims to connect that history to today’s progressive social movements to advance economic and racial justice.”

Fighting for knowledge

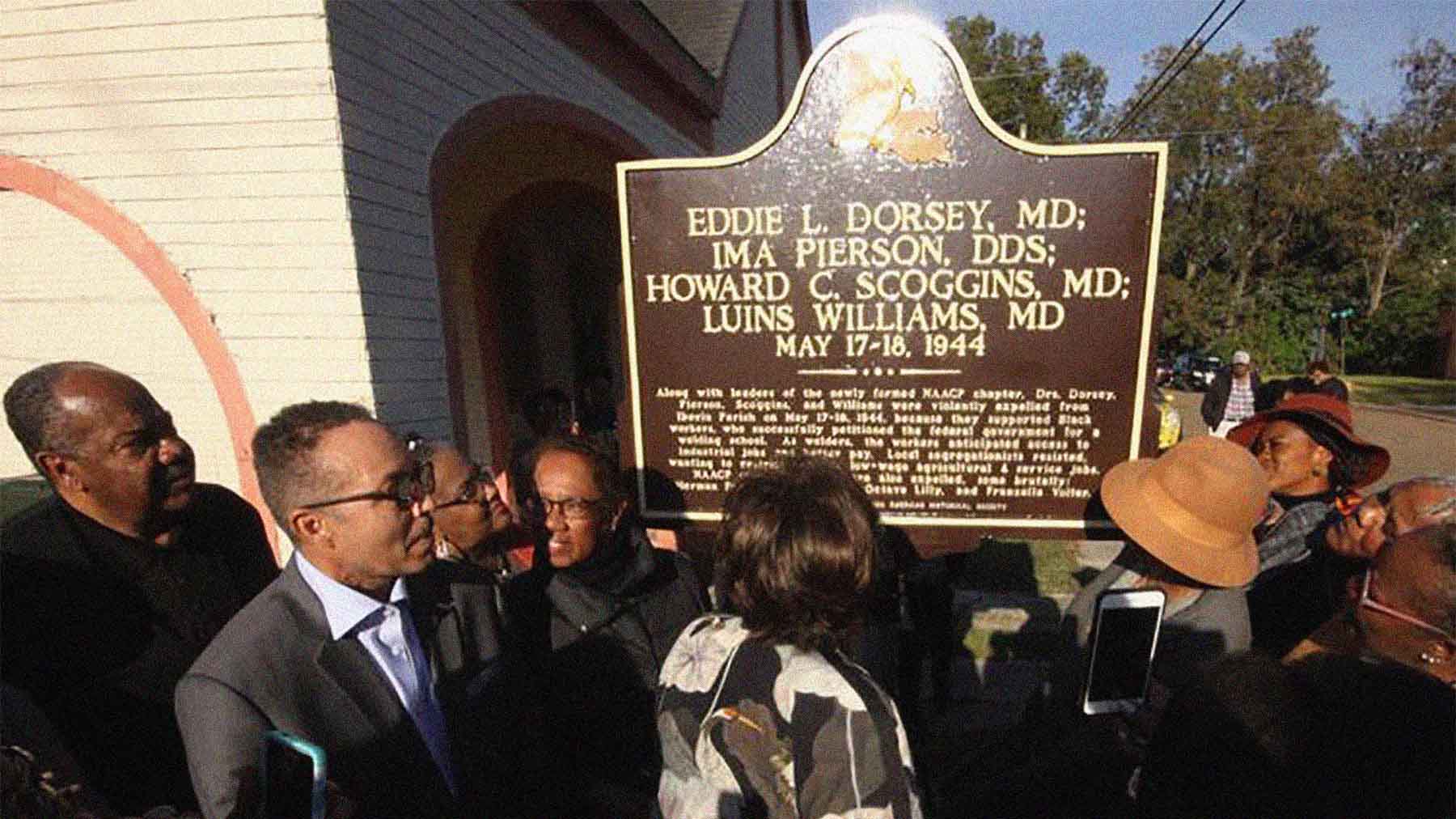

During one week in May 1944, a dozen Black citizens were forced to leave New Iberia. Among them were four doctors and four civil rights leaders — physicians Eddie L. Dorsey, Howard C. Scoggins and Luins Williams; dentist Ima A. Pierson; and community leaders Herman Faulk, J. Leo Hardy, Octave Lilly Jr. and Franzella Volter. Several of them were severely beaten before being dumped at the city limits. Hardy would die within months from his wounds, while Pierson would go through life with a metal plate in his skull because of his beating at the hands of Iberia Parish deputies.

The impetus for those attacks came after a chapter of the NAACP was established in the summer of 1943. It was at the height of World War II, and skilled welders were at a premium. The NAACP chapter, led by Hardy as its president, supported the idea of establishing a school where Black students could learn to weld, creating the first conflict with Porter, the school superintendent.

Eventually, in March 1944, the funding for the school was approved. Hardy reached out to the federal government, specifically the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) and the War Manpower Commission, for help in getting the school off the ground. The FEPC sent a mediator who left New Iberia thinking everything was on track for the classes to begin.

Initially, there were to be two classes, one during the day and another in the evening, to allow workers to take classes around their existing jobs, primarily working the sugar fields in Iberia Parish.

On May 7, under Porter’s control, the school opened. But there was only one class, offered at night. On the first day, Porter cut that session short, saying the noise bothered the school’s white neighbors. The classes were then rescheduled for the daytime, and some students could not attend. Hardy again asked the FEPC to intervene.

A week later, Iberia Sheriff Gilbert Ozenne had his deputies pick up Hardy and bring him to his office, where Porter and the sheriff confronted him. According to his statement later, Hardy said Ozenne and Porter “browbeat” him, then told him he should leave town by 10 a.m. When he was still in New Iberia the next evening, four sheriff’s deputies in a black car arrived at the saloon where Hardy was talking with friends and again took him to Ozenne’s office. There he was beaten and dumped on the outskirts of town.

Hardy called Scoggins, who administered first aid and took him to nearby Lafayette. He brought Hardy clean clothes in Lafayette the next day. Hardy then took a train to Monroe, putting New Iberia in his past.

On the evening of May 17, three deputies rounded up Faulk, Pierson and Williams. After deputies beat the trio, they were also dumped out of town. Lilly visited Pierson in Lafayette and decided to leave New Iberia. Volter and Dorsey did the same.

Upon hearing of the expulsions, Scoggins barricaded himself in his house overnight and left for Lafayette the morning of May 18.

Adam Fairclough, professor emeritus of Leiden University in the Netherlands, documented the episode in New Iberia in an academic paper published in 1987 and later in his book Race and Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana, 1915-1972. According to Fairclough, the incident in New Iberia was not unusual at the time.

“This was going on everywhere,” Fairclough said at a symposium held to mark the unveiling of the historic marker in front of Dorsey’s home in 2019, 75 years after the beatings. “This was not just Iberia Parish. What happened, the use of deputy sheriffs as enforcers, was just how it was done across the South.”

In his research, Fairclough relied heavily on the statements of those expelled, FBI reports and the work of two NAACP attorneys, one of whom was Thurgood Marshall, who would eventually become the first Black justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. But even with documentation, witnesses and evidence, no federal charges were filed.

Seeking closure

Even as the story of the expulsion becomes better known, Porter’s name still stands high above the predominantly Black neighborhood off Center Street. According to school officials, there is no plan to remove the signage or rename the facility, even though it is currently shuttered.

When contacted for comment, then-Iberia Parish Schools Superintendent Carey Laviolette deferred comment to the school system’s legal counsel, J. Wayne Landry. Landry said he was only vaguely aware of the name being a problem because of a public comment session during a board meeting 10 years ago.

“My recollection is that no one has come before the board to have it changed,” Landry said. “Other than that one guy protesting during a meeting, I haven’t heard it come up.”

The effort was more involved than a simple statement at a meeting, however. Records of a 2012 petition drive can be found in the archives of The Daily Iberian, the local newspaper. And the attention given to the exiling of the Black doctors and leaders — and Porter’s part in the events — has grown as the story has been published more widely in recent years.

“What really offends me is that people really think we as a Black community are that ignorant, that we don’t see it,” Hayes said. “Who are these people? They know how to make money because of the connections that have been laid down for decades. Start investigating how almost a quarter of the community lives below the poverty line. There is no anger there. We just need to understand how people have gotten to where they are.”

For Hayes, having the city face its history can help the community understand why some conditions — like concentrated poverty in certain neighborhoods and not in others — still exist. That history can also offer solutions, if they are studied and embraced.

“Why can’t we make gestures to everyone in the community, a signal to the public that things will change?” she asked. “History can be used to unite communities when people come to understand how we got to where we are. Hopefully, from our study of history, we develop empathy for each other. We come to care for each other.”

English said: “It’s tragic that members of the Black community were terrorized and murdered by white supremacists simply because they wanted to educate and train others to have a better quality of life. However, having spaces named after those who had a role in perpetuating racial injustice continues to oppress and harm members of the Black community and it serves as a constant reminder of the racial violence of the past and present.”

Top picture: Descendants of the Black doctors and community leaders expelled from New Iberia in 1944 gathered in 2019 to celebrate the placement of a memorial plaque at the former residence of Dr. Eddie L. Dorsey, 75 years after he was forced to leave New Iberia. (Credit: Dwayne Fatherree)