Broken glass and scattered pieces of wood clamored across the porch of the white clapboard house tucked into the 6-acre orange grove in Mims, Florida. When the fog and dust lifted, the house’s columns stood off-kilter and the contents of the bedroom spilled forth into the dirt outside.

People heard the blast from a mile away, shattering the peace of Christmas 1951. The next afternoon, the front-page headline of the Orlando Evening Star read, “Bomb Kills Mims NAACP Leader.”

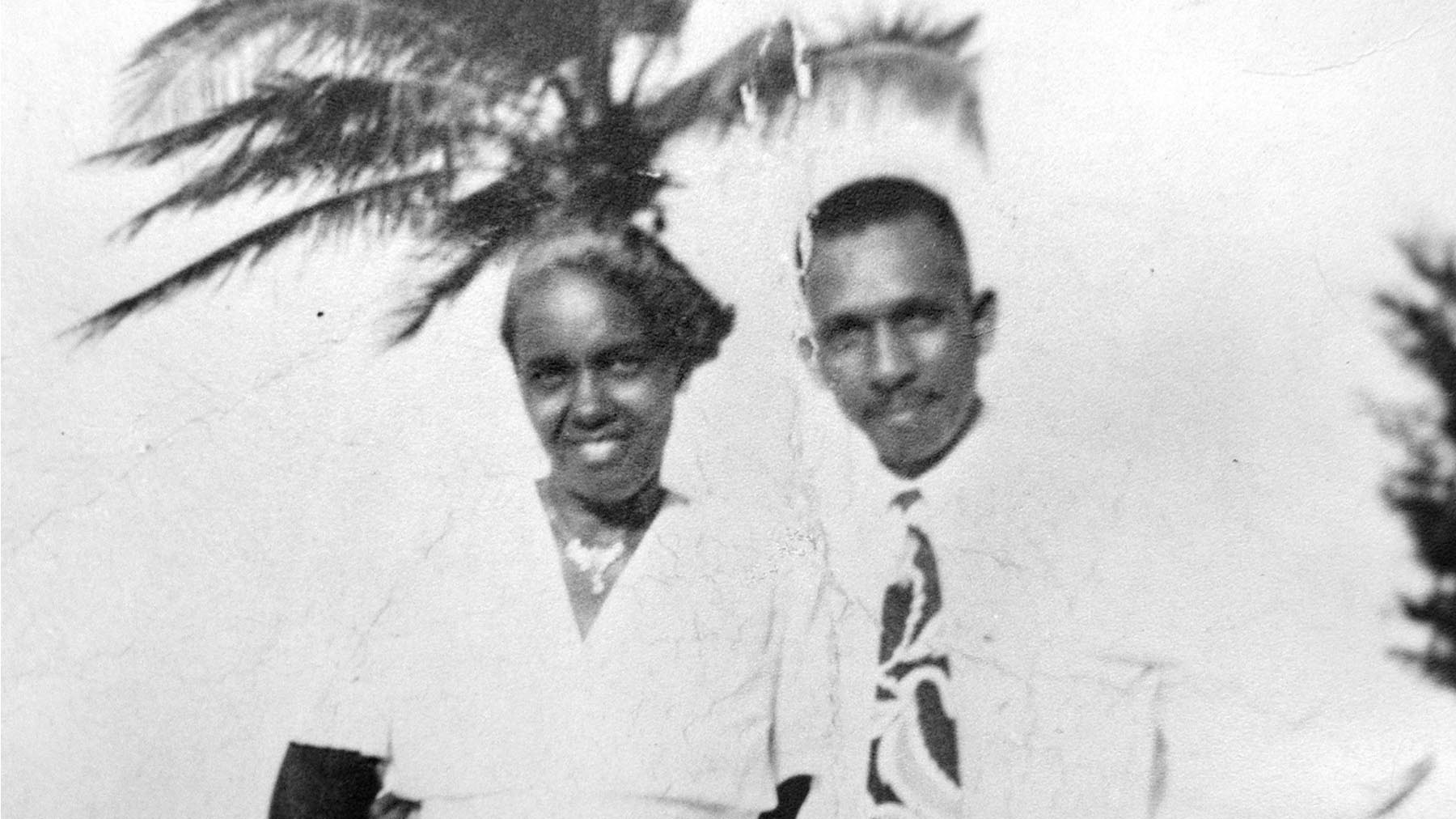

At the time of their deaths, Harry T. Moore, and his wife, Harriette, had registered more than 100,000 Black voters across Florida – the highest Black voter registration rate in the South. It was a bold feat in a state with more lynchings per capita than any other in the country, and where Ku Klux Klan members acted with impunity. To this day, their murders remain unsolved, and to many, the Moores’ heroism remains unknown. A new Florida bill seeks to honor these civil rights martyrs by protecting the right to vote that cost them their lives.

The Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Florida Voting Rights Act seeks to enshrine voting protections and mechanisms into state law. Last summer, the Southern Poverty Law Center and civil rights advocates began working with Florida legislators to craft the bill, which strengthens voting rights and access to the ballot. State Sen. Geraldine Thompson and state Rep. LaVon Bracy Davis filed the bill in January.

The bill comes at a time when several states – particularly those in the South – have passed laws limiting voter access by restricting early voting and criminalizing people or groups that assist voters in casting their ballots, among other tactics.

“It’s been a nightmare of changes for voting rights in Florida over the past five years,” said Jonathan Webber, the SPLC’s Florida policy director. “Seemingly every year, Republicans have sponsored and passed major changes to our voting laws. Laws that make it harder for people to vote, harder for people to register, harder for groups to do outreach to get people to register. Floridians deserve every opportunity to vote, and there are people and groups like us on their side, trying to help them exercise their most fundamental human right.”

The road to the bill’s passage will be difficult. Florida Republicans, hostile to such legislation, hold a supermajority in the Legislature. Thompson and advocates encourage Floridians to call and write their state legislators to show their support for the bill.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision, the nation has seen a deluge of laws threatening to suppress the vote, particularly in the Deep South, where the SPLC focuses its efforts. The court decision removed the requirement that states and jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination against voters must seek federal approval before implementing new voting laws. Since the removal of this requirement known as preclearance, numerous restrictive laws have passed in 29 states, including Florida.

Such attacks, particularly those aimed at Black voting power, only ramped up after the 2019 election of Gov. Ron DeSantis, who’s backed by a Republican-controlled Legislature.

The new bill would help restore some Black voting power in Florida, advocates say.

“My grandfather was very adamant that Black people had to register to vote to somehow chart a different course,” said Skip Pagan, the son of the Moores’ youngest daughter, Evangeline. “A bill of this nature is a great evolution of the work he did.”

Since 2019, the state has charged with voter fraud at least 20 people who say they did not know they were ineligible to vote – and 14 of those people who were arrested are Black. Florida has changed voter registration laws and imposed steep fines on voter assistance groups for registration errors. People of color are five times more likely to register through third-party organizations. The state also attempted to dismantle a majority-Black voting district to weaken voters’ legislative power.

The Florida legislation, also known as SB 1522 in the state Senate and HB 1035 in the state House of Representatives, would include preclearance protections and expanded language options for voting materials. It would deputize the Florida Department of Highway Safety to pre-register qualifying individuals to vote when they renew their driver’s license.

The bill also would allow voters to register at any time, including on Election Day; establish a central database where formerly incarcerated people could check their eligibility; and reinstate voters’ ability to request permanent vote-by-mail ballots, as opposed to current law, which requires people to request them each cycle.

“There’s been a continuing erosion of voting rights in the state of Florida,” said Thompson, whose state Senate district covers west Orange County, including the town of Eatonville – the oldest Black incorporated municipality in the country – and downtown Orlando. “This bill seeks to undo some of the damage that’s been done to silence the voices of people the majority would prefer not to hear.”

‘The most dangerous Black man in Florida’

Throughout the 1930s until his untimely death at 46 on Christmas Day 1951, Harry Moore drew motivation from the prospect of advancement for Black Americans and the fulfillment of their enfranchisement. He lost his job, received death threats on himself and his family and ultimately died for his commitment to civil rights. And it all happened before the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement as recognized by historians, which began with the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board decision that desegregated schools.

In 1934, Moore founded a chapter of the NAACP in Brevard County, located on Florida’s east coast. Trained as an educator, he began advocating for equal pay for Black teachers, who made half as much as their white counterparts. With the assistance of then-NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall, Moore eventually filed a lawsuit against the state in 1938. It was the first suit in the Deep South demanding pay equality among Black and white teachers. Though they lost the case, it opened the door for many similar suits filed across the South, some of which were ultimately successful.

In 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional all-white primary elections that had allowed Democratic parties across the South to effectively function as private membership-based clubs. From this point on, both of the country’s political parties were open to Black voters. When the Moores began traveling throughout Florida in 1934 to register voters, only 5% of eligible Black voters were registered. Following the ruling, the Moores registered 116,000 Black voters to the Democratic Party – 31% of the state’s eligible Black voters.

Moore wrote to political candidates seeking their platforms and questioned them directly about how they would support Black communities. Then, he educated Black voters about which candidates could best serve their needs. He was building a political machine.

Author Ben Green, who in 1999 published his biography Before His Time, described Moore as a grassroots organizer as opposed to a big, charismatic leader. Between 1945 and 1951, Green said Moore personally investigated every lynching that took place in the state. As the scope of his work grew, so too did the danger.

“He was totally fearless,” Green said. “Teacher salaries will get you fired, lynchings will get you killed, but now you’re going to determine the outcome of the governor’s race? That will get you assassinated. To those who wanted him gone, he was clearly the most dangerous Black man in Florida.”

Things came to a head after Moore became involved in the 1949 Groveland rape case, in which four young Black men were accused of sexually assaulting a white woman. One of the accused men fled and was later murdered in an act of white vigilantism. Following the arrest of the three remaining men, a white mob viciously attacked the city’s Black neighborhood. When two of the men were convicted and sentenced to death by an all-white male jury, Moore campaigned for a new trial.

The Florida Supreme Court upheld the convictions, but in 1951, the U.S. Supreme Court granted their appeal. But as the town’s sheriff drove two of the men to a pretrial hearing, he shot them, killing one man and injuring another. The sheriff claimed self-defense. Moore pushed back against this narrative, calling for the sheriff’s suspension and indictment.

Florida was like a powder keg in the months leading up to the deadly bombing on Moore’s home. The last six months of 1951 saw 12 bombings, suspected to have been detonated by the KKK. The bombing of the Moore home would be the last of that year.

That Christmas Day, the Moores and one of their daughters, Annie, along with Harry’s mother, Rosa, had celebrated the holiday at Harriette’s mother’s home, nearby. That evening, when the family returned home, Green said they celebrated the couple’s 25th wedding anniversary over cake. Harry talked a little about the couple’s love. Then they sliced the cake, each with their hand on the knife’s hilt, just as it had been on their wedding day. The family had decided to defer opening presents until the youngest daughter could join them the next day on her way down from Washington, D.C. When their daughter, Evangeline, reached the train station in neighboring Titusville, her sister, Annie, and her grandmother, Rosa, and her entire extended family were present – Evangeline’s mother and father were not.

Harry died on Christmas night. Harriette survived the bombing but died nine days later in the hospital.

“To know that you will lose your life for the work you’re doing – many people wouldn’t continue to do that,” said Pagan, the grandson. “So much blood was shed, so many sacrifices were made, a price was paid for the freedoms we enjoy.”

Photo at top: Harriette and Harry T. Moore in West Palm Beach, Florida, in 1950. (Credit: The Washington Post via Getty Images)