The Ku Klux Klan, with its long history of violence, is the oldest and most infamous of American hate groups. Although Black Americans have typically been the Klan’s primary target, adherents also attack Jewish people, persons who have immigrated to the United States, and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Top Takeaways

In 2024, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) underwent notable reconfigurations among its ranks. Two of the larger factions — the Old Glory Knights and the Loyal White Knights — either faded from relevance or ceased operations altogether. In the wake of these dissolutions, newer groups, such as the Maryland White Knights and the Sacred White Knights, emerged, gaining traction from members of the defunct chapters. This year has also seen an increase in collaborative efforts between Klan groups and other white supremacist organizations. The United Klan Nation notably co-hosted events with the Aryan Freedom Network, while antisemitic Christian Identity and Klan-affiliated networks, including the Church of the Keystone Knights and Kingdom Identity Ministries, overlapped through shared leadership.

Key Moments

Newer and recently revitalized chapters have led efforts to gain a stronger foothold in mainstream American society. Historically, this pattern aligns with a familiar Klan tactic: heightened visibility during periods of actual or perceived sociopolitical strife. This year saw a persistent focus on online “activism,” marked by a gradual shift from such niche platforms as Stormfront, MeWe and Gab to larger social networks including Facebook and X (formerly Twitter).

The emergence of the Maryland White Knights and the Sacred White Knights underscores this reshuffling. The Maryland White Knights appear to have formed from the remnants of the Old Glory Knights, while the Sacred White Knights seem to have risen from the dissolution of the Loyal White Knights. Meanwhile, the Ku Klos Knights have resurfaced, and the Silent Knights are actively recruiting. Another key connection has been between the United Klan Nation and the Aryan Freedom Network, evident through shared events and mutual promotion.

Perhaps most emblematic of the Klan’s reemergence was the Trinity White Knights, who led Klan flyering efforts this year and closely monitored the political landscape for opportunities to enter mainstream conversations. Mere days after President Donald Trump’s inflammatory claim that Haitian immigrants were eating dogs and cats, the Trinity White Knights began distributing flyers and recruiting based on that dangerous and unfounded narrative.

What’s Ahead

While Klan activity is likely to remain relatively stagnant overall, 2025 may bring further reshuffling and reorganization within Klan ranks due to the recent collapse of major chapters like the Old Glory Knights and the Loyal White Knights. Chapters such as the Trinity White Knights, who have proven particularly active this year, will likely continue to be prominent in the coming year.

Moreover, with the anti-immigration and anti-diversity agenda of the new Trump administration, the Klan may increasingly seek mainstream legitimacy, attempting to move further from the fringes of society. This prospect is bolstered by the enduring appeal of slogans from the 1920s-era Klan, such as “true Americanism” and “America for Americans,” which persist as central themes in Klan rhetoric and literature. These ideas, powerful in their nostalgia and nationalist appeal, suggest that dismissing the Klan as a relic or conflating it with broader white supremacist movements — as is often done in right-wing media — could obscure the group’s specific and ongoing efforts to adapt and insert itself into contemporary American discourse.

Background

In 1865, at the conclusion of the Civil War, six Confederate veterans gathered in Pulaski, Tennessee, to create the Ku Klux Klan, a vigilante group mobilizing a campaign of violence and terror against the African American people that benefited from the progress of Reconstruction. As the group gained members from all strata of Southern white society, it used violent intimidation to prevent Black Americans — and any white people who supported Reconstruction — from voting and holding political office.

To maintain white hegemonic control of government, the Klan, joined by other white Southerners, engaged in a violent campaign of deadly voter intimidation during the 1868 presidential election. From Arkansas to Georgia, thousands of Black people were killed. Similar campaigns of lynchings, tar-and-featherings, rapes and other violent attacks on those challenging white supremacy became a hallmark of the Klan.

The first leader or “grand wizard” of the Ku Klux Klan was Nathan Bedford Forrest, a well-known Confederate general. Within the structure of the Klan, he directed a hierarchy of members with outlandish titles, such as “imperial wizard” and “exalted cyclops.” Hooded costumes, violent “night rides” and the notion that the group made up an “invisible empire” conferred a mystique that only added to the Klan’s infamy.

After a short but violent period, the “first era” Klan disbanded when it became evident that Jim Crow laws would secure white supremacy across the country. However, the legacy of the original Klan, and the figureheads of the Confederacy before it, have been enshrined across the country in the “Cult of the Lost Cause.” Only in recent years — after gaining significant attention through large counterprotests and after deadly attacks from far-right extremists — have states and localities started removing these statues and renaming public spaces. On July 9, 2020, Tennessee’s State Capitol Commission voted to remove the bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest from the state Capitol building. It was subsequently removed on July 23, 2021, and placed in the Tennessee State Museum.

In 1915, the Ku Klux Klan was revived by white Protestants near Atlanta, Georgia. In addition to the group’s anti-Black ideological core, this second iteration of the Klan also opposed Catholic and Jewish immigrants. A growing fear of communism and immigration broadened the Klan’s base throughout the South and into the Midwest, with a particular stronghold in Indiana. By 1925, when its followers staged a march in Washington, D.C., the Klan had as many as 4 million members and, in some states, considerable political power. A series of sex scandals, internal battles over power and newspaper exposés quickly reduced the group’s influence.

The Klan arose a third time during the 1960s to oppose the Civil Rights Movement and attempt to preserve segregation as the Chief Justice Earl Warren-led U.S. Supreme Court substantiated civil rights in multiple rulings. Bombings, murders and other attacks by the Klan took a great many lives. Murders committed by Klansmen during the civil rights era include four young African American girls killed in 1963 while preparing for Sunday services at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and the 1964 murder in Mississippi of civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner.

Throughout the second and third eras of the Klan, many Black Americans left Southern states in the Great Migration. While those who moved North were seeking economic prosperity and social opportunities, they were also hoping to escape the racial terror centered around the Klan’s ideological stronghold in the South. With over 6 million Black Americans taking part in this migration, the demographics of the country shifted dramatically.

With the conclusion of the Vietnam War in 1975 and the subsequent return of American soldiers, several key figures arose within the Klan. Louis Beam, upon his return from Vietnam, joined the Alabama-based United Klans of America. His teachings on “leaderless resistance” and early adaptation to technological advances helped bridge neo-Nazi and Klan groups into the organized white power movement. Similarly, David Duke — who founded the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in 1975 — maintained a distinctly antisemitic hatred that closed ideological gaps with neo-Nazis.

Through a series of court cases aimed at bankrupting the Klan and closing the group’s paramilitary training camps, the organization has been weakened. Internal fighting and government infiltrations have led to an endless series of splits, resulting in smaller, less organized Klan chapters. Given the Klan’s insistence on remaining an “invisible empire,” it is nearly impossible to estimate how many active members there are today. However, it is fair to assume that the infighting, rigid traditions and the uncouth image of the Klan are not attracting significant new membership.

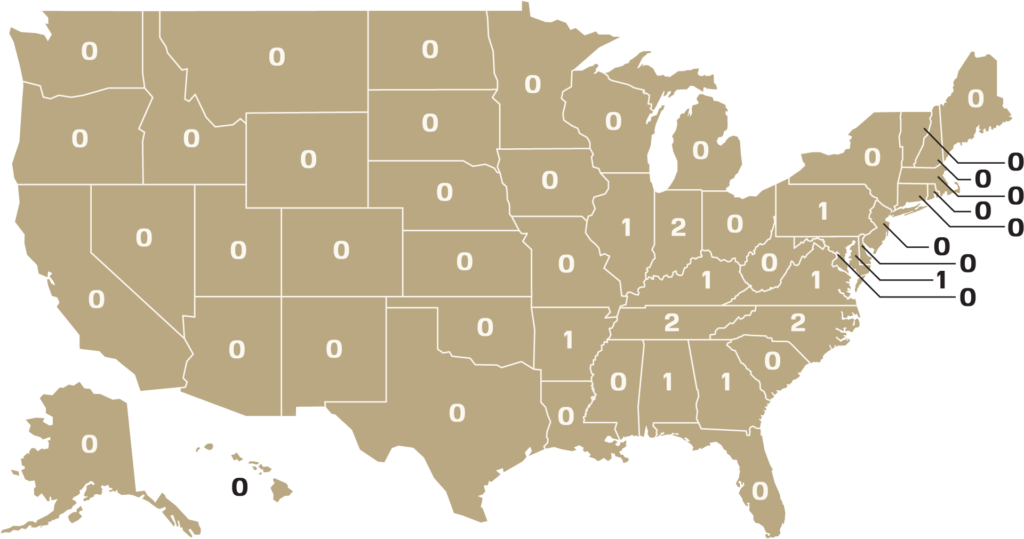

2024 Klan Hate Groups

Christian Revival Center

Harrison, Arkansas

Church of the Keystone Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Ragland, Alabama

East Coast Knights of the True Invisible Empire

Pennsylvania

Ku Klos Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Nashville, Illinois

Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Pelham, North Carolina

Virginia

Maryland White Knights

Maryland

Nordic Order of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Indiana

Old Glory Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Santa Fe, Tennessee

Sacred White Knight

Pelham, North Carolina

Silent Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Auburn, Indiana

Trinity White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Maysville, Kentucky

United Klan Nation

Tennessee

United Northern and Southern Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Ellijay, Georgia