White nationalist groups espouse white supremacist or white separatist ideologies, often focusing on the alleged inferiority of nonwhite groups. They frequently claim that white people are persecuted by society and even the victims of a racial genocide. Their primary goal is to create a white ethnostate. Groups listed in a variety of other categories, including Ku Klux Klan, neo-Confederate, neo-Nazi, racist skinhead and Christian Identity, could also be fairly described as white nationalist.

Top Takeaways

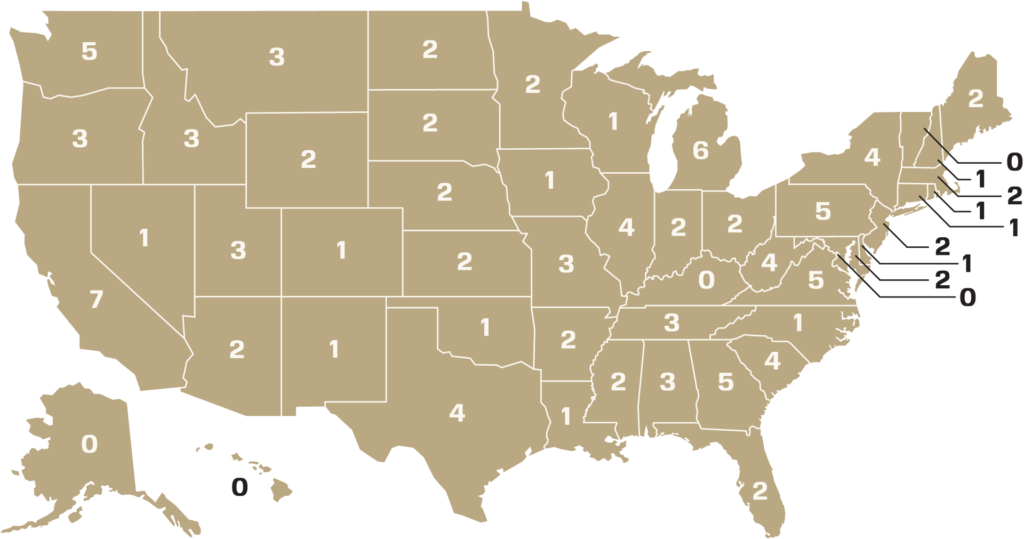

In 2024, there were 110 active white nationalist groups across the United States — down from a historic high of 165 in 2023. White nationalists have been mobilized by the broader far-right reactionary movement that has taken hold in American politics in recent years. Groups have been particularly active in on-the-ground organizing, participating in their own demonstrations and appearing alongside more mainstream right-wing groups and individuals, especially at anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-abortion events.

Many white nationalists see their primary goal as challenging the neoconservative wing of the American right. Figures including Nick Fuentes, a livestreamer who was present outside the U.S. Capitol at the Jan. 6 insurrection, are trying to harness the grievances of white, right-leaning Americans into an openly ethnonationalist political movement they hope will become the core of the Republican Party. Evidence that the American right is hardening its views and embracing exclusionary and authoritarian politics — Donald Trump’s electoral victories; the adoption of white nationalist conspiracies like the “great replacement” among Republican politicians; the Jan. 6 insurrection; successful attacks on reproductive rights; antipathy toward policies aimed at achieving racial equity and inclusion; and the widespread demonization of LGBTQ+ people, migrants, non-Christians and others — has given white nationalists hope that their views will continue to march toward the center of American politics.

Though Fuentes continues to have broad influence among today’s white nationalists, the movement has few prominent leaders. Some, like Patriot Front leader Thomas Rousseau, hold dictatorial sway over their own group, but shy away from building their own public profile. Others, like the leaders of the now-defunct National Justice Party, reached their pinnacle of influence in the early years of the Trump presidency and have since seen their dominance wane.

Many newer white nationalist groups have autonomous chapters that embrace similar strategies but do not answer to a single, national leader. That creates a low barrier to entry that can bring a swift upswing in membership as it did for Active Clubs, which grew from 12 chapters in 2022 to 39 in 2023. But the lack of organizational oversight can also lead to disengagement and declining participation, as it apparently did for the white nationalist training group, which declined to 35 chapters in 2024. The founder of Active Clubs, Robert Rundo, offers his followers guidance on how to embrace a white nationalist “lifestyle” — including purchasing clothing from his brand Will2Rise, embracing hypermasculinity, adopting an intense fitness regimen and consuming the work of white nationalist musicians and authors he promotes — but he has not instituted a system of bylaws, nor does he dictate the activities of individual Active Club chapters. His influence within the group has receded in the past year as he sat in prison awaiting trial for riot charges. In September, Rundo pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 24 months in prison.

The white nationalist movement continued to use on-the-ground activism in 2024 — a trend seen across the hard right. While the movement saw a huge upswing in demonstrations and protests in the early years of the Trump presidency, that activity waned after the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally in 2017, which brought intense public and legal scrutiny to participating groups and individuals. In the aftermath, many leaned into their belief that no “political solution” would solve the problem of multiracial democracy — only political violence. While white power activists and other far-right extremists continue to engage in acts of violence, threats and intimidation campaigns, they also feel empowered to once again return to the streets. Such groups as Active Clubs and Patriot Front have, for example, protested LGBTQ+-inclusive events and drag shows, and held unannounced “flash” demonstrations aimed at intimidating communities.

Key Moments

As it has since its founding in 2017, Patriot Front continued to host theatrical flash demonstrations throughout 2024. On July 2, approximately 150 members marched through Nashville masked and in uniform.

This year several civil cases against Patriot Front wound through the courts across the U.S. According to court documents, in April 2024, U.S. District Court judge Indira Talwani issued a default judgement against the group after Rousseau and other Patriot Front members failed to respond to the complaint. The case stems from a 2022 Patriot Front march in Boston during which several group members assaulted a Black artist. Rousseau and his loyalists are also facing lawsuits in Richmond, Virginia, and Fargo, North Dakota, for their alleged role in destroying works of public art. In Richmond, Rousseau and other members of Patriot Front stand accused of destroying a mural to Arthur Ashe, a famous Black tennis star from the city. In Fargo, Rousseau and other group members are accused of destroying a mural at the International Market Plaza. In both cases, Patriot Front members are accused of painting over the artwork and using spray paint to stencil Patriot Front branded messages. Both civil cases are ongoing.

In a separate criminal case, Rousseau was arrested in February and charged for his involvement in a 2017 torchlit march through the University of Virginia the night before the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. At the August 11, 2017, nighttime march, which echoed the Klan’s torchlit marches in the 20th century, the marchers chanted “Jews will not replace us,” and taunted students were perceived to be Jewish. Rousseau accepted a disorderly conduct conviction in October 2024 as part of an Alford plea, which lets a defendant plead guilty and maintain their innocence. The judge ordered Rousseau to pay court costs and barred him from the University of Virginia campus.

While social media outlets have made some strides in recent years to hinder the spread of hate and harassment on their platforms, Twitter, now called X, has erased much of that progress since billionaire Elon Musk came to the helm in October 2022. The account belonging to Nick Fuentes, for example, was reinstated, and he has amassed over 470,000 followers.

What’s Ahead

Members of the white nationalist movement are placing much of their energy into harnessing the anger and resentment of Trump supporters into a broad authoritarian movement. They hope to convince white Americans that they are persecuted by “anti-white” ideas and policies, including the adoption of inclusive education in schools. This movement could cause further disruption and violence in a bid to push the Trump administration further to the right.

The continued radicalization of the GOP has greatly aided the white nationalist movement, exhibited by the party’s embrace of such racist concepts as the “great replacement,” vilification of immigrants, attacks on reproductive care, and demonization of queer and trans people.

White nationalists will continue to abet the broader right’s attacks on marginalized people and communities through propaganda production, participation in protests and other forms of intimidation and even violence. X’s choice to reinstate extremists and slacken enforcement of hate speech policies will mean that more people will be exposed to white nationalist propaganda and harassment.

Background

Adherents of white nationalist groups believe that white identity should be the organizing principle of the countries that make up Western civilization. White nationalists advocate for policies to reverse changing demographics and the loss of an absolute, white majority. White nationalists see ending nonwhite immigration, regardless of legal status, as an urgent priority — frequently elevated over other racist projects, such as ending multiculturalism and miscegenation — in order to preserve white, racial hegemony.

White nationalists seek to return to an America that predates the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Both landmark pieces of federal legislation are cited as the harbingers of white dispossession and the so-called “white genocide” or “great replacement,” the idea that whites in the United States are being systematically replaced and destroyed.

These racist aspirations are most commonly articulated as the desire to form a white ethnostate, a calculated idiom white nationalists favor to obscure the inherent violence of such a radical project. Appeals for the white ethnostate are often disingenuously couched in proclamations of love for members of their own race, rather than hatred for others.

This platitude collapses under scrutiny. One favorite animating myth of white nationalists is the victimhood narrative of Black-on-white crime — the idea that the dominant white majority is under assault by supposedly violent people of color. Another deeply related myth is the deceptively titled “human biodiversity,” or the pseudoscientific belief that different races are genetically different, and that these differences influence propensity toward criminality and other traits. Appeals to the bogus “empirical science” of human biodiversity are frequently coupled with thinly veiled nods to white, racial superiority.

In addition to obsession with declining white birth rates, these themes inspire some of the most powerful propaganda that animates and drives the white nationalist movement.

Adherents frequently cite the “great replacement” theory, a racist conspiracy narrative that argues elites, often powerful Jews and/or left-leaning elites, intend to “replace” white Americans through immigration and lower birth rates. This narrative of “white extinction” has found multiple manifestations through American history.

White nationalists frequently cite American Renaissance, a pseudo-academic organization dedicated to spreading the myth of Black criminality, scientific racism and eugenic theories, to support their pseudoscientific claims. Its annual conference, a multiday symposium with a suit-and-tie dress code, is a typical early stop for newcomers to the organized white nationalist movement.

Antisemitism is deeply woven into the modern-day white nationalist movement, whose adherents use Jews as scapegoats for their perceived cultural and political grievances. White nationalists often argue that Jews are orchestrating the “great replacement” — making people of color, whom they believe to be less intelligent and more easily manipulated, into the numerical majority of Western countries in a bid to secure complete political control. Kevin MacDonald, the author of The Culture of Critique, a trilogy of books alleging a Jewish control of culture and politics with evolutionary psychology, has been cited by innumerable white nationalists as the person who introduced them to the idea of a Jewish conspiracy.

White nationalists also commonly pass through paleoconservatism, an anti-interventionist strand of libertarianism that seeks to limit government, restrict immigration, reverse multicultural programs and deconstruct social welfare programs. Some of the most prominent voices in the movement’s recent history, including Richard Spencer, Jared Taylor and Peter Brimelow, did stints at Taki’s Magazine, the most prominent paleoconservative journal. Prominent paleoconservatives, such as Pat Buchanan, have mirrored white nationalist arguments regarding demographics. For instance, in his 2001 book , Buchanan argued that these declining white birth rates and an “immigrant invasion” will transform the United States into a so-called “Third World” nation by 2050, as the text responsible for their awakening or “red pill.”

Strategies for pursuing the white ethnostate fall into two major categories: mainstreaming and vanguardism. Mainstreamers believe that infiltrating and subverting the existing political institutions is the only realistic path to power. They aspire to convert disaffected “normies” to their politics and advocate for white nationalists to seek esteemed and influential positions in society where they can access resources otherwise unavailable to avowed racists. This path often requires white nationalists to disguise their politics and compromise on their most extreme positions. Mainstreaming allows those sympathetic to white nationalism to pursue or enact policies furthering white nationalist priorities. These policies are not always exclusive to white nationalism, such as immigration restriction or the elimination of social welfare programs.

Vanguardists believe that revolution is the only viable path toward a white ethnostate. They believe that reforming the system is impossible and therefore refuse to soften their rhetoric. They typically seek to reform what they believe to be an “antiwhite” establishment through radical action and often openly advocate for the use of violence against the state and people they perceive to be their political enemies. Through acts of violence, they believe they can further polarize politics and accelerate what they view as the inevitable collapse of the United States.

The racist “alt-right” was the most prominent strand of the white nationalist movement during the 2016 presidential campaign and the first half of the Trump presidency. It was a political moment that allowed activists to temporarily paint over cracks that have historically divided the movement. Composed of a broad coalition of far-right activists and groups, the alt-right hoped to push ethnonationalism into the political mainstream. But after the “Unite the Right” rally, alliances faded into infighting when the movement came under intense public and legal scrutiny, including a civil suit that ultimately found many of the most prominent alt-right leaders and groups liable for $26 million in damages.

Growing disillusioned with trying to achieve political goals through mainstream channels such as electoral politics and mass organizing, an “accelerationist” wing, focused on bringing about the collapse of society, has gained a prominent place within the movement. This violence-obsessed subset predominantly congregates on the messaging platform Telegram, as well as other “alt-tech” platforms that do not moderate users’ content.

Still, especially in the aftermath of the Jan. 6 insurrection, a large part of the white nationalist movement remains focused on bending the mainstream right toward open ethnonationalism. Racist influencers like Nick Fuentes, for example, spend much of their time critiquing Republican officials and operatives. These actors want to build alliances with Republican elected officials, create their own political parties and institutions and, especially, cultivate a cohort of young, radical activists within the GOP.

Groups listed in a variety of other categories, including Ku Klux Klan, neo-Confederate, neo-Nazi, racist skinhead and Christian Identity, can also be fairly described as “white nationalist.” As organizational loyalty has dwindled and the internet has become white nationalism’s organizing principle, however, the ideology is best understood as a loose coalition of social networks orbiting online propaganda hubs and forums.

2024 White Nationalist Hate Groups

* – Asterisk denotes headquarters.

Active Club

Alabama

Arizona

Huntington Beach, California

Sacramento, California

Atlanta, Georgia

Coeur D’Alene, Idaho

Chicago, Illinois

Indiana

Kansas

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Fargo, North Dakota

Ohio

Medford, Oregon

Portland, Oregon

Pennsylvania

South Carolina

South Carolina — Palmetto

South Dakota

Parker County, Texas

San Antonio, Texas

Salt Lake City, Utah

St. George, Utah

Pasco, Washington

Spokane, Washington

West Virginia

America First Foundation

Chicago, Illinois

American Freedom Party

Los Angeles, California

Illinois

New York

American Renaissance/New Century Foundation

Oakton, Virginia

Antelope Hill Publishing

Quakertown, Pennsylvania

Arktos Media

Chelsea, Michigan

Blood River Radio

Bartlett, Tennessee

Christ the King Reformed Church

Charlotte, Michigan

Continental Resistance

California

Michigan

Council of Conservative Citizens

Potosi, Missouri

Counter-Currents Publishing

San Francisco, California

Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation

Vienna, Virginia

Full Haus

Purgitsville, West Virginia

Gab

Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania

Homeland Institute

Town of Hancock, Maryland

NeoKrat

Tacoma, Washington

New Columbia Movement

Georgia

Taylor, Pennsylvania

Dallas, Texas

New Jersey European Heritage Association

New Jersey

Northwest Front

Bremerton, Washington

Occidental Dissent

Eufaula, Alabama

Occidental Observer

Hayden, Idaho

Occidental Quarterly/Charles Martel Society

Atlanta, Georgia

Patriot Front

Alabama

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Patriotic Flags

Summerville, South Carolina

Political Cesspool

Bartlett, Tennessee

Radix Journal

Whitefish, Montana

Red Ice

Harrisonburg, Virginia

School of the West

Rio Vista, California

Shieldwall Network

Mountain View, Arkansas

Stormfront

West Palm Beach, Florida

Sugar Tree Legion

New York

The Colchester Collection

Machias, Maine

The Right Stuff

Hopewell Junction, New York

VDARE Foundation

Berkeley Springs, West Virginia

White Rabbit Radio

Dearborn Heights, Michigan

Will2Rise

Spotsylvania, Virginia

William McKinley Institute

Atlanta, Georgia