The policing of gender has become a common tactic among some policymakers, whether it’s banning trans people in sports, legislation regulating bathroom usage or the targeting of drag performances.

Such attacks can echo the past. The targeting of drag performances is no exception — especially when one considers drag’s history within the Black community.

Drag, a performance art that sends up strict binary gender norms, is a form of gender expression and a protest art form that lampoons restrictive expectations for how to live. Drag ballroom culture’s historical origins are about more than challenging rigid gender norms — performers also lampooned white people’s expectations for Black self-expression. This history illustrates how the policing of Blackness, gender and sexuality are inherently intertwined.

History shows that drag has always played a crucial role in challenging white supremacy. From the 19th century to today, drag has been a cherished art form of liberating self-expression and self-determination for marginalized people. Drag performers upend traditional gender roles by making their bodies a site of creative rebellion and vibrant resistance to authoritarianism. As anti-LGBTQ+ animus propels government intrusion into individual freedom of expression, bodily autonomy and privacy in the U.S., restrictions on gender expression are reemerging. This development places Black and Brown LGBTQ+ people, those whose existence and expression represent the antithesis of white supremacy, in harm’s way.

In 2023, the Southern Poverty Law Center documented 200 anti-drag incidents. The SPLC and the LGBTQ+ advocacy group GLAAD have each documented efforts of anti-LGBTQ+, white nationalist, neo-Nazi, antisemitic and antigovernment groups to stop public displays of drag. These groups are invested in strengthening the gender hierarchy and stricter gender norms that help maintain white supremacy. These different movements target drag — a visual defiance of the hypermasculinity hard-right groups demand — with particular venom. Their attacks on drag help reveal how innate male supremacy is to these movements — and how it helps bridge the gaps between these movements.

The policing of gender has escalated through anti-trans bathroom bans and anti-trans sports bans. In 2023, the SPLC reported that public policy attacks on LGBTQ+ people are intentionally couched in scientific rhetoric meant to hide the white supremacist origins of medical standards used to define gender and race. Biological markers for supposedly normal gender expression are based mostly on studies of white people, while the history of American medical science is littered with examples of racist eugenic experimentation that denied the humanity of people of color.

Looking at the history of gender policing, in the U.S. what defines gender is a combination of norms, expectations and assumptions enforced through social interactions, pseudoscience, and, with growing regularity, legal proscriptions that hold society to white traditionalist standards of masculinity and femininity. The origin of drag artistry teaches remarkable lessons on how the policing of gender tends to result in the over-policing and incarceration of people of color and how liberated gender expression can challenge white supremacy.

Drag origins: Historically a form of post-slavery, Black queer resistance

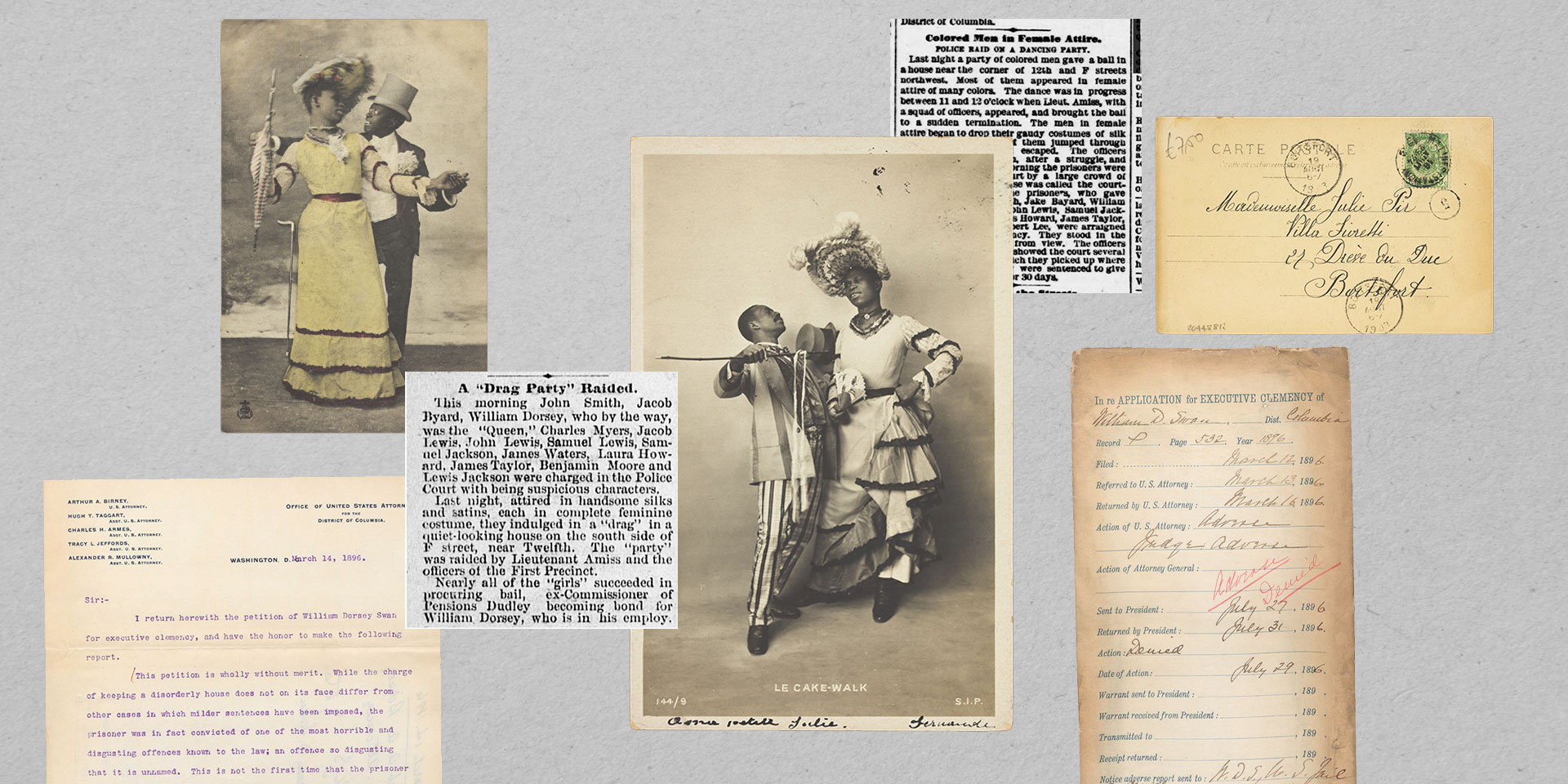

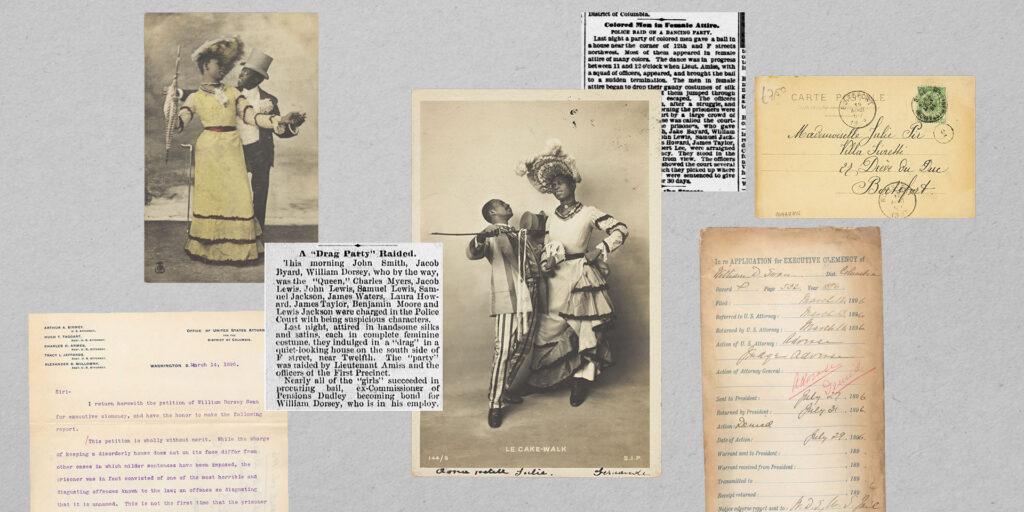

The art form of drag has its roots deeply embedded in Black queer celebrations following emancipation. Drag ballroom culture was formed in a time of extreme gender policing and Jim Crow laws. The modern drag ball originated with the parties of William Dorsey Swann, known to friends as “The Queen.” Swann was born into enslavement in 1860 in Hancock, Maryland.

In the 1880s, Swann began hosting secret dancing competitions disguised as family gatherings in his Washington, D.C., home. Swann’s guests had masculine, working-class jobs like butler, coachman, cook and messenger. Many of those who frequented Swann’s drag parties had likely been, at most, one generation removed from enslavement and likely came to Washington to pursue economic prosperity and distance from their former enslavers. The “House of Swann,” situated off L Street, became one of the first known venues of drag and a refuge for those who had to contend with the horrors of racism and gendered policing during the Jim Crow era.

Guests wore extravagant attire. Some men wore suits, but many donned silk and satin dresses, corsets, bustles, long hose and slippers. Swann adapted the key components of modern ballroom culture, like competitive and glamorous exaggeration of gender, directly from the cakewalk dance, a practice that forced enslaved people to compete in a dance to entertain their enslavers.

Called a “cakewalk” because decorated cakes were presented as prizes, the events included singing, dancing and minstrel-style pageantry. Some historians speculate that performers used these events to discreetly mock the egregious opulence of enslavers’ Southern plantation balls.

By the time of Swann’s drag fêtes, the cakewalk had evolved into both a symbol of freedom and mockery of enslavement. Swann helped transform cakewalks into one of the most vital forms of expression of queer identity. Today, the echoes of Southern charm and hospitality of drag culture serve as a reminder of how Swann flipped the script of the cakewalk and cemented a legacy of reinvention and reclamation of Black culture through the art of drag itself.

Swann’s story was forgotten until 2005, when an academic, Channing Gerard Joseph, came across an article from April 13, 1888: “Negro Dive Raided. Thirteen Black Men Dressed as Women Surprised at Supper and Arrested.” Joseph found other news accounts of the event that revealed Swann attempted to hold off police, allowing a dozen of his guests to escape. “The Queen,” who was dressed in a “gorgeous dress of cream-colored satin,” reportedly told off the police lieutenant overseeing the raid, exclaiming, “You [are] no gentleman.”

Swann was jailed multiple times. In 1896, he was falsely charged with “keeping a disorderly house,” a euphemism for a brothel, and was sentenced to 10 months in jail. Swann wrote to President Grover Cleveland and requested a presidential pardon. Though his request was denied, it was the first documented political action taken by a member of the LGBTQ+ community for the LGBTQ+ community, according to Joseph.

Swann’s gatherings shaped drag as we know it today, illustrating that drag has always been rooted in both Black culture and LGBTQ+ resistance in the face of rigid white and heterosexist gender norms.

Gender policing

The moral panic incited by modern anti-LGBTQ+ groups relies on proximity to cisgender, heterosexual whiteness to define normal racial and gender expression. Modern bans on drag are legacies of the state-sponsored policing of appearance and behavior in public life that predate Swann. In 1845, in response to anti-rent protesters who disguised themselves by cross-dressing, New York passed a masquerade law that prohibited people from wearing anything that might hide their identity from police.

From 1845 to 1900, these laws spread to 34 cities in 21 states and morphed from prohibiting disguises to explicitly policing cross-dressing. These laws were part of larger anti-vice legislative campaigns that emphasized “public decency” and criminalized poverty, sex work and addiction.

Targets of these laws included women who wore pants, “female impersonators” and anyone with “dress not belonging to his or her sex.” In 1890, Dick Ruble (who also went by Mamie) was arrested for wearing men’s clothes. In court, Ruble declared, “I’m neither a man nor a woman and I’ve got no sex at all.” The judge believed Ruble was mentally ill and sentenced them to the Insane Asylum of California at Stockton, where they died of tuberculosis 18 years later.

Policing public spaces, including bathrooms, was the major feature of Jim Crow laws premised on racist fears of racial mixing and racist myths of Black hypersexuality and criminality. Hard-right groups’ false claims that expanding civil rights protections to trans people in public spaces endangers women and girls is borrowed entirely from this legacy of segregationist rhetoric.

Anti-trans sports bans, bathroom bans and locker room bans foment hatred and paranoia that is often unleashed not only at trans people, but also cisgender people of color. In 2024, Algerian boxer Imane Khelif became a global target for anti-trans hate as hard-right agitators who wrongly insisted her success in the Olympics against Western competitors couldn’t be possible unless she were not a “real woman.”

Learning from and preserving LGBTQ+ history

The intersection of racism and gendered policing still exists today in the over-policing of Black and Brown LGBTQ+ people. In 2024, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found LGBTQ+ people are less likely to call law enforcement and more likely to experience chance police-initiated contact (being stopped, searched, arrested and detained) than white LGBTQ+ people.

The ACLU reported that Black and Brown LGBTQ+ people were more likely to report offensive language and physical force from police. At the same time, the Willliams Institute found LGBTQ+ people are five times more likely to experience violent crimes than non-LGBTQ+ people, and highlighted that Black LGBTQ+ people in their study experienced the highest rates of victimization.

The lesser-known history of drag uncovers a rich legacy of defiance against white supremacy. The story of Swann, unlike the stories of many formerly enslaved Black people, was at least partially preserved and shows that Swann was truly an icon and an example for courageous resistance to white supremacy. Swann’s life also teaches that LGBTQ+ people’s resistance to oppression has repeatedly been led by Black and Brown people and that the movement for LGBTQ+ rights has always been intertwined with racial and gender justice.