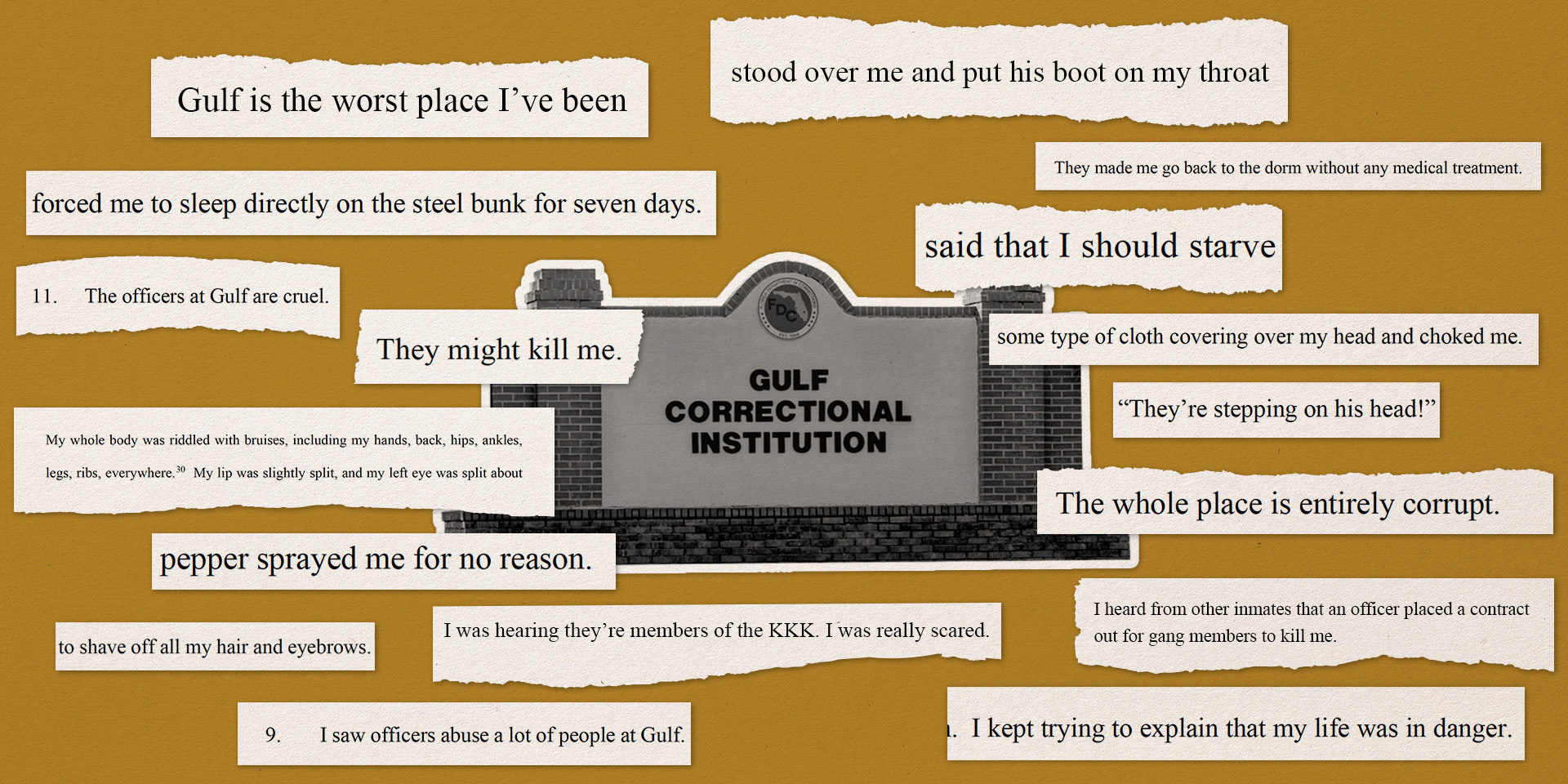

Head strikes, body slams, stabbings, chemical agents sprayed within inches of the face — this isn’t a dramatized portrayal of prison violence for a splashy television series. This is the daily reality for incarcerated people at Gulf Correctional Institution and many other Florida prisons. Gulf is one of the most brutal prisons run by the Florida Department of Corrections (FDC), where a culture of violence, degradation and abuse can regularly lead to serious injury and even death.

Over the last decade, thousands of people incarcerated in FDC have reported excessive force and staff misconduct to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). To corroborate the harm experienced by people in the custody of Florida’s prison system, a small team of attorneys, investigators, paralegals and administrative staff at the SPLC interviewed incarcerated victims at Gulf, the prison from which they received a high concentration of complaints about excessive force.

Drawing on these first-person accounts as well as thousands of public records from the past 10 years, the SPLC’s new report, Florida’s Gulf Correctional Institution: A Culture of Violence, a Code of Silence, explores the human toll of prison brutality, shining the light on the root causes of violence and the alarming lack of accountability at Gulf and in FDC.

Why has violence become so widespread at Gulf Correctional Institution?

Florida has one of the country’s largest prison populations, with FDC incarcerating more than 89,000 individuals. However, these prisons have faced significant staffing shortages leading to overcrowding.

In 2021, the correctional officer vacancy rate — or the percentage of available positions for correctional officers that are unfilled — exceeded 10% for 46 FDC facilities. While the state Legislature was able to shrink that number by approving a slight bump in officers’ salaries in 2022, the statewide vacancy rate remained stubbornly high at more than 25%.

That number paled in comparison to the vacancy rate at Gulf Correctional Institution, a facility located in a rural area of the Florida Panhandle near the city of Wewahitchka, with the capacity to hold about 1,600 people. As of September 2023, the operational staff vacancy rate at Gulf was 58%, tied for third highest in the state, according to consultants hired by FDC.

The burden of overcrowding and understaffing often results in dangerous consequences for people incarcerated at Gulf. Without adequate officer and investigator staffing, prison gangs thrive and perpetrate violence at the facility. Nearly every person interviewed reported that gangs essentially run the institution, with some officers afraid to intervene in attacks, indifferent to the violence, or complicit in their actions. For example, interviewees reported that certain officers frequently allowed people to enter through locked doors into dorms or cells without authorization to assault others at the facility or transfer contraband.

Overcrowding also leaves incarcerated individuals with few places to turn to for protection. In FDC’s 50 major institutions, seven annexes and seven private facilities, only a handful of prisons have protective management units. Official FDC policy is for people who fear being assaulted to notify staff. Staff should then place them in solitary confinement pending review for protective management — a process known as “checking in.” But overcrowding results in many requests being denied. Instead, FDC’s practice is to transfer people to another institution only after they have been severely injured in an attack.

How do staff contribute to the culture of violence at Gulf?

Unfortunately, violence is not limited to interactions between incarcerated people. In many cases, the officers themselves contribute to the dangerous environment for people incarcerated at Gulf and other FDC facilities. Findings from the SPLC investigations and interviews showed a pattern of some FDC officers sadistically beating and abusing incarcerated people with impunity. Victims reported officers repeatedly slamming, punching and kicking those who were fully restrained.

Certain Gulf staff also feed the culture of violence through overly harsh punishments and degradation of the people in their care, including:

- Property restriction, which involves stripping someone in solitary confinement down to their underwear, taking all their property and then leaving them to sleep on a cold, steel bunk for up to three days.

- Denying meals for innocuous misconduct and delivering “air trays” to people in solitary confinement; for the benefit of the prison cameras, officers deliver a meal tray covered by a lid, with no food under that lid.

- “Standing on the grate,” a practice of forcing people to stand on the storm drains on the yard for hours, sometimes stripped down to their underwear or with their arms and legs in uncomfortable positions.

- “Catfishing,” a practice in which officers order barbers to involuntarily shave off all of someone’s hair and eyebrows.

- Spraying chemical agents like pepper spray on various parts of the body, including the mouth, ear, groin and buttocks.

- Verbal abuse and harassment, including the use of racial slurs as well as threats of physical and sexual violence.

Frequent mistreatment can cause incarcerated people at Gulf to feel hostile and distrustful toward staff, which can result in some people rebelling, overreacting or even becoming violent. In turn, this misconduct can validate officers’ perception of the need for harsh or punitive treatment. Verbal abuse, for example, can escalate “minor” confrontations into full-blown use-of-force incidents that result in needless violence and injuries to both staff and incarcerated people at the facility.

How have FDC and staff members at Gulf escaped accountability for excessive violence?

Integral to staff culture at Gulf is the “code of silence” or “blue wall” typical of most law enforcement agencies. Researchers have documented the pervasive peer pressure within law enforcement agencies to shield their inner workings from public knowledge and accountability. This code ordinarily develops between prison employees who bond over stressful and dangerous working conditions and hardens into an “us-versus-them mentality” between staff and incarcerated people. A central tenet of the code is that prison staff must never “rat out” one of their own.

How does this play out at Gulf? Records show that many Gulf officers not only failed to report or intervene during staff misconduct, some also falsified records and lied to cover up their colleagues’ misdeeds, even in the face of video evidence to the contrary. Similarly, some nursing staff failed to document use-of-force injuries, including head trauma, cuts and broken bones.

Exacerbating this lack of accountability is the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for investigating officer misconduct and referring matters for criminal prosecution or administrative discipline. Records show that some OIG investigators rush investigations, while some inspectors have ties to their subjects, calling into question their objectivity. Investigations also rely on direct video evidence to substantiate allegations of misconduct, allowing officers to perpetrate abuse in known blind spots throughout the prison.

Of the approximately 1,100 incidents for which FDC produced records to the SPLC, the OIG pursued criminal prosecution against officers in just one incident involving excessive force and one involving contraband. With the OIG referring very few, if any, officers for prosecution or administrative discipline, officers are left to answer only to institutional management, who often ignore patterns of abuse, rubber stamp their misconduct or transfer abusive officers to other institutions.

What can be done to reduce violence in Florida prisons?

Gulf Correctional Institution — and FDC generally — is a system that damages, rather than rehabilitates, its population. It subjects incarcerated people to years of systemic violence and abuse before releasing them back into their communities, which increases the risk of future crimes and makes Florida less safe.

To fix this counterproductive and costly system, the SPLC has outlined a number of prison reforms that can help reduce violence in Florida’s facilities:

- Florida should reduce its prison population to ensure a safe and manageable staff-to-prisoner ratio. The state can work to achieve this by: repealing mandatory minimum sentencing; increasing the amount of rehabilitation credit an incarcerated person can earn to reduce their length of their sentence; increasing the number of work-release, community correction and reentry programs to support successful transition back into communities; and diverting individuals who commit nonviolent offenses into programs that address the underlying causes of criminal behavior.

- The state should invest in greater oversight of its facilities and staff. Florida should create a separate agency — completely independent from FDC — that is responsible for reviewing all uses of force and officer misconduct allegations and holding staff accountable. FDC should require all correctional officers that have direct contact with incarcerated people to wear body cameras. FDC should further require that officers independently document uses of force before they have an opportunity to review camera footage and investigators interview them.

- FDC should improve working conditions and training for correctional staff. FDC should: pay officers living wages; increase mental health and other support to prevent or address burnout among staff; increase de-escalation and conflict resolution training for staff and incarcerated people; and require racial bias training for correctional staff.

The SPLC acknowledges the risk of retaliation that many subjects can face for participating in these interviews and is grateful to all contributors for their bravery and candor. Learn more about their experiences and dive deeper into failures of FDC and the policy recommendations of the SPLC by reading the full report, Florida’s Gulf Correctional Institution: A Culture of Violence, a Code of Silence, which contains detailed citations to support the SPLC’s findings.

Illustration at top by the SPLC.