Realizing they had been abandoned, panic began to set in for those trapped in their cells.”

New Orleans once had a jail large enough to house a small town. It was built to keep the city safe — until Hurricane Katrina exposed otherwise.

Most jails and prisons throughout the South have two things in common. First, they are spaces well known for violence and exploitation. Second, they disproportionately house Black people. These two points are not only linked to each other, but have also been a historic throughline stitching together different eras of the jail.

In antebellum Louisiana, the first version of the Orleans Parish jail was built in 1721 in the French Quarter’s Jackson Square and was a place to detain and punish runaway enslaved people. Captured runaways were subject to torture and leased for profit by enslavers. According to author Rashauna Johnson in her book Slavery’s Metropolis, the jail “categorized, housed, and exploited suspected runaways; inflicted corporal punishment on recalcitrant slaves at their masters’ request; incarcerated whites and free blacks … and exploited slave and free inmates’ labor to build the city.” By the 1830s, 80% of the jail’s forced labor came from Black people.

The theme of violence toward Black incarcerated people would endure throughout the 20th century, as people in the 1960s and 1970s would complain of how “physical and sexual assault were frequent and the threat of attack was constant.” In fact, federal Judge Herbert Christenberry declared in a 1970 consent decree that “the conditions of plaintiffs’ confinement in Orleans Parish Prison so shock the conscience as a matter of elemental decency and are so much more cruel than is necessary to achieve a legitimate penal aim that such confinement constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution.” Through all of this, the jail maintained a profitable work release program where men worked regular jobs in the community during the day, returned to jail at night, and then were forced to reimburse the sheriff for room and board, travel and other debts out of their salary.

Living in the Wake: The Enduring Legacy of Hurricane Katrina is a series of essays that examine what the failures of the past can teach leaders about creating the kinds of inclusive, forward-thinking policies New Orleans needs to transform communities that have endured decades of neglect. Read all the essays.

By 2005, the Orleans Parish jail (by this time known as the Orleans Parish Prison) would swell to nearly 6,300 incarcerated people in 7,600 jail beds across a dozen buildings — enough to hold every current undergraduate at Tulane University. New Orleans would grow to have the highest jail incarceration rate of any major city in the U.S. — five times the national average. Its local jail population would include people held for any number of minor allegations — public drunkenness on Bourbon Street, marijuana possession, trespassing — but all unable to post bail and purchase their freedom. In fact, only 5% of criminal court convictions were for violent offenses, while 67% of convictions were for simple drug possession in 2003-2004.

Before Hurricane Katrina, Black people made up the extreme majority (90%) of the jail’s incarcerated, while making up 66% of New Orleans. They included people whom state and local governments paid a per diem of $22.39 to the jail — over $100,000 every day for everyone in custody. Local courts and bail agents would profit from bonds and fees levied by judges to people often unable to afford them. So throughout the hundreds of years since the New Orleans jail’s slavery origins, local incarceration has maintained a financial incentive to funnel large amounts of Black people through its system for profit.

This may explain the fateful decision of then-Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman in 2005. When asked by a reporter what he would do with the thousands of people still incarcerated in his jail the day before Katrina would reach landfall, Gusman replied: “[W]e have backup generators to accommodate any power loss. … We’re fully staffed. We’re under our emergency operations plan. … [W]e’ve been working with the police department — so we’re going to keep our prisoners where they belong.”

Where incarcerated people “belong” is a simple, yet profound statement on our expectations of carceral systems. It is a statement that tells us that historically violent and inhumane spaces are acceptable for certain people. Even if operating a mega-jail threatens morality or human life, the notion assumes it is necessary to keep our streets “safe” and stay “tough on crime.” It assumes that potentially drowning incarcerated people in an impending hurricane is easier than considering their humanity.

90%of the New Orleans jail population was Black when Hurricane Katrina hit

On Aug. 29, 2005, Katrina came to test those assumptions.

Katrina would baptize 80% of New Orleans under her rain and floodwaters shortly upon arrival. In the jail, water rose from knee-high to waist-high to chest-high in a matter of hours, forcing sewage and muck to regurgitate from toilets on the lower floors. The jail’s generator quickly gave out, leaving the facility without lights or air conditioning in the sweltering heat. Realizing they had been abandoned, panic began to set in for those trapped in their cells.

“The water started rising, it was getting to here,” said Earrand Kelly, one of the incarcerated men interviewed after the event, as he pointed at his neck. “We was calling down to the guys in the cells under us, talking to them every couple of minutes. They were crying, they were scared. The one that I was cool with, he was saying, ‘I’m scared. I feel like I’m about to drown.’ He was crying.”

It wasn’t until midnight on Aug. 29, after a full day of pummeling under a Category 3 hurricane, that Sheriff Gusman sent for help to evacuate the jail — a move incredibly more difficult to execute with so much of New Orleans now underwater. The evacuation wouldn’t be completed until Friday, Sept. 2. By that time, many of the correctional officers had abandoned their posts, leaving people incarcerated there without food, clean water or medicine for days.

By the time small boats arrived to eventually transport everyone from the jail to more secure ground at the Interstate 10 overpass, a troubling dynamic had developed — over 500 people were now missing and unaccounted for, according to Human Rights Watch. A jail facility, ironically built to be aware of where people were at all times, now had hundreds vanish while in its custody. However, despite evidence from news investigations and firsthand accounts from incarcerated people, Gusman would insist that there were no casualties or missing people from the jail. According to him, “They’re in jail, man. They lie. … Don’t rely on crackheads, cowards and criminals to say what the story is.”

Years after Katrina’s aftermath, many of the dynamics that fueled a carceral system are still present today. The New Orleans jail is still entirely violent and disproportionately filled with Black people. In fact, a federal judge called New Orleans’ jail system “an indelible stain on the community” in 2013 while approving another consent decree to address the blatant disregard of constitutional standards.

The post-Katrina New Orleans jail is still dangerous enough to have 66 deaths occurring since 2006, including many deaths resulting from violence or suicide. In 2012, Terry Smith, a veteran, was severely beaten by a correctional officer, suffering permanent brain damage that would ultimately contribute to his death in 2017 at age 71. In 2016, 15-year-old Jaquin Thomas would die by suicide after having been assaulted by other people in the New Orleans jail weeks prior. Currently, Black males like Smith and Thomas compose 88% of the jail population but only 19% of New Orleans residents.

Given these historically violent outcomes — slave exploitation, Katrina disappearances, jail assaults — it would beg a legitimate question: What exactly is our primary goal with incarceration? Giving an incarcerated senior citizen brain damage arguably provides no contribution to a safer New Orleans. However, if there is a cultural narrative that says certain people must be controlled for public safety to feel valid, then that same narrative will justify the jail — and all the inhumanity that’s in it.

Case in point, Gov. Jeff Landry pushed legislation in 2024 to roll back the minimum age Louisiana could charge a youth in adult court from 18 to 17. Landry did so in the name of reining in youth “criminals,” stating on social media, “No more will 17-year-olds who commit home invasions, carjack, and rob the great people of our State be treated as children in court. These are criminals and today, they will finally be treated as such.” However, since the legislation passed, 69% of 17-year-olds convicted as adults have been arrested for nonviolent offenses, countering the narrative concerned with street violence. For anyone, especially children, charged with nonviolent crimes, the full weight of a potentially deadly carceral system could easily do more harm than good.

Many New Orleanians were essentially drowning in the legal system before Hurricane Katrina came and exposed incarceration’s systemic harms. The jail became a tool to criminalize people who could be better served outside of a jail cell — such as people with mental health issues or substance use disorders, or young people making youthful mistakes. Many Black people fell victim to a narrative that said New Orleans could incarcerate its way into becoming a safer city. New Orleans, and anywhere else in the South with a similar history, deserves different priorities that produce different outcomes.

The South needs policies that prioritize people over political rhetoric. The South needs elected officials willing to invest in rehabilitation over retribution. The South needs a cultural narrative that prioritizes the humanity of all its communities. Until these needs are met, we run the risk of repeating history whenever the next great storm inevitably arrives.

How to effect change?

- Require more data transparency, independent oversight and hiring diversity from local law enforcement, while training them to reimagine safety during weather emergencies.

- Incorporate restorative measures and community alternatives, such as diversion programs, that decrease the number of incarcerated youth, particularly keeping them out of adult facilities like the Orleans Parish Jail and Angola prison.

Organizations that offer help

Many organizations also fulfill the needs on a local level. They give voice to directly impacted communities, advocate for policy change, and reimagine a better South on a daily basis. Please consider supporting and engaging with partners like these who are doing the work locally:

Delvin Davis is the SPLC’s interim director of Policy Research.

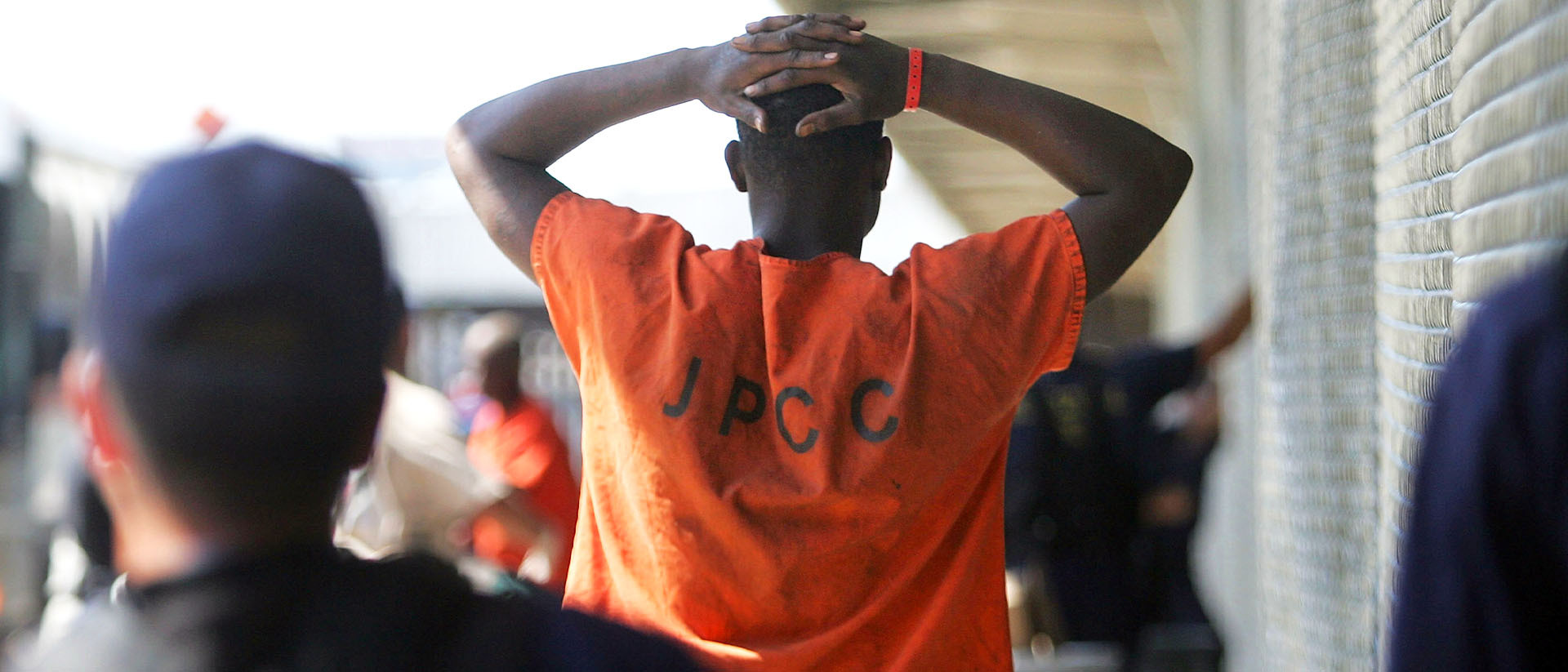

Image at top: In a photo from Sept. 6, 2005, a man enters a temporary prison inside a Greyhound bus terminal in New Orleans. About 150 people who were accused of crimes in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina were held at the makeshift prison before being transferred to a state prison to stand trial. (Credit: Mario Tama/Getty Images)