The time is now for federal funding to adequately support communities that are disproportionately impacted by natural disasters and climate change by focusing preparation and recovery efforts on rebuilding communities, not just rebuilding property.”

In late August 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a storm with sustained winds of 125 mph when it made landfall, caused widespread destruction across Florida, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana. Katrina changed lives across the country, with many families losing their belongings, communities, and ultimately, even their loved ones. Research suggests that in Louisiana alone, more than 1,000 people died in the storm.

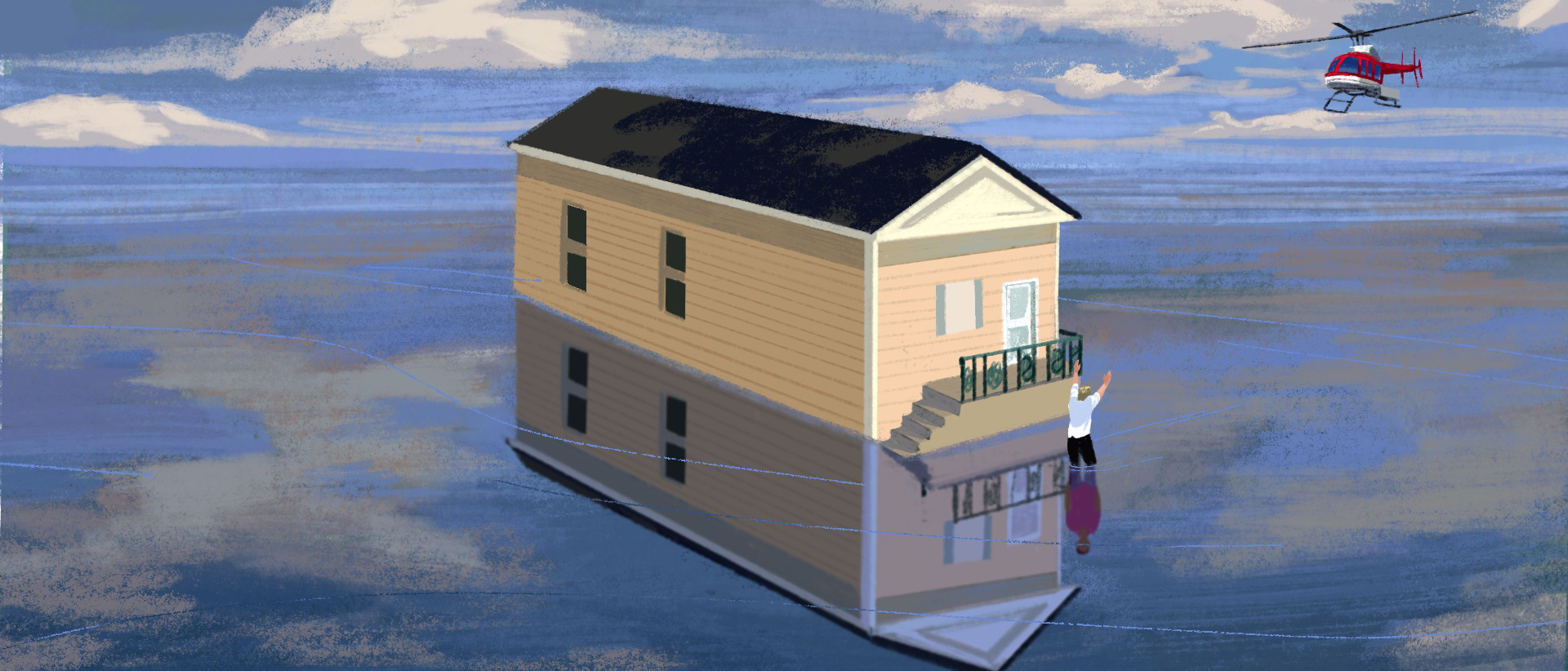

Many were harmed or displaced during the actual hurricane, but what impacted communities across New Orleans even more was the flooding following the breached floodwall. Weaknesses in federally constructed floodwalls and levees exposed the long-standing inequity in disaster aid soon after the winds died down. From a helicopter 500 feet above New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward following the storm, Col. Terry J. Ebbert, the city’s then-head of Homeland Security, reported, “There’s nothing out here than can be saved at all.” However, there were in fact many people and families in need of help, and many communities that deserved assistance as much as the next.

Unfortunately for some, help never arrived, and the belief that New Orleans was beyond saving likely influenced hurricane preparation, the emergency response post-landfall, and ultimately, which communities around the city had the opportunity to rebuild with disaster-related federal funding in the years to follow. Poverty impacts one’s ability to prepare for weather-related events, to evacuate when necessary, and even how communities and families are able to rebuild following a natural disaster.

In the video: Two New Orleans musicians discuss how the Musicians’ Village rebuilding project became the “heartbeat” of the Lower 9th Ward. (Credit: Kathleen Flynn and Jane Geisler)

Like the breached levees, Hurricane Katrina exposed inequity in the federal emergency management system that had existed for decades. Had consistent and guaranteed federal funding been available to Louisiana and its localities, the hurricane’s impact may not have been as devastating. Following the storm, there was a delay in response time — shortages in food, water, and other lifesaving supplies grew as response efforts had to be coordinated and officials had to choose what and who to prioritize with limited resources. Evidence shows that the number of climate-related disasters, including hurricanes, tornadoes and flooding — especially in the Deep South — are growing, meaning there may be many more difficult choices for government officials to make in the future.

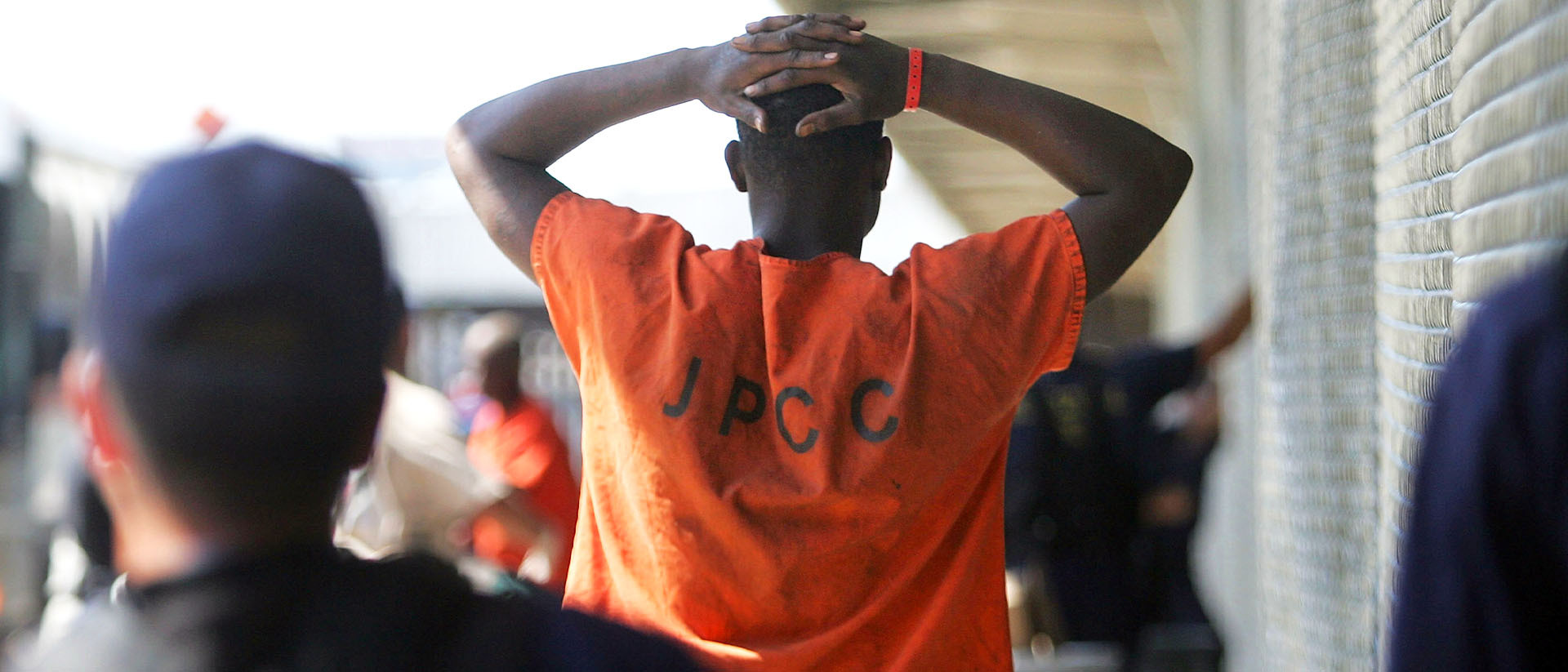

As with Hurricane Katrina, some communities will be more at the mercy of government decisions than others. Research shows that communities of color are more at risk for experiencing the impacts of these weather-related events, and, in the South, Black people especially are more likely to die during severe weather at higher rates than every ethnic group except Indigenous people. Thus, the time is now for federal funding to adequately support communities that are disproportionately impacted by natural disasters and climate change by focusing preparation and recovery efforts on rebuilding communities, not just rebuilding property.

Climate Change Uniquely Impacts the Deep South

As noted, communities of color are more likely to be hit the hardest by climate-related events like hurricanes. Hurricanes and other extreme weather events like flooding and tornadoes are becoming more commonplace, particularly across the Deep South as the sea level rises and the climate changes. Weather-related disasters impact many communities across the country. However, there are several reasons why the Deep South is particularly impacted when these events occur, and many of them are rooted in the Deep South’s disproportionately high number of people experiencing poverty.

Living in the Wake: The Enduring Legacy of Hurricane Katrina is a series of essays that examine what the failures of the past can teach leaders about creating the kinds of inclusive, forward-thinking policies New Orleans needs to transform communities that have endured decades of neglect. Read all the essays.

In 2005, with nearly half a million residents, New Orleans had one of the highest levels of income inequality in the United States. At that time, nearly 28% of residents lived below the federal poverty line. Before Katrina, the majority of the city’s residents were African American.

On Aug. 28, 2005, a mandatory evacuation was finally ordered for all civilians within the city of New Orleans — less than 24 hours before Katrina’s expected landfall. However, with such short notice to evacuate before the storm, many people and families with low incomes faced obstacles to leaving, including a lack of transportation and the financial resources to travel. Instead of leaving for areas outside of the storm’s trajectory, many sought refuge in hurricane shelters. The Louisiana Superdome, the city’s largest storm shelter, housed at least 25,000 people hoping to ride out the storm. With more than 80% of the city underwater in the wake of the storm, thousands more would arrive at the Superdome in search of somewhere safe once the water began rising.

For many people and families with low incomes, the decision to evacuate before an impending hurricane is often made for them. This was no different with Katrina. Even in the present day, research finds that poverty inhibits one’s ability to prepare for and recover from storms.

Recovery Efforts Are Unequal Across Neighborhoods

Indeed, communities with lower incomes are at an increased risk of experiencing natural disasters, and at the same time, communities with lower incomes also struggle to rebuild after climate or weather disasters strike. Following Katrina, communities across New Orleans experienced recovery efforts differently depending on the section of the city — and ultimately property values — of the neighborhood one lived in. In New Orleans, poverty tracks closely with race because of differences in opportunity.

28%Percentage of New Orleans residents in 2005 living below the poverty line.

An evaluation of the Road Home Program, the state’s largest housing recovery program, found people living in neighborhoods with lower incomes had to cover more of their home rebuilding costs since the Road Home grants did not cover all the costs. This is because the formula that calculated each grant was based on the lesser of two amounts: a home’s value before the hurricane or the cost of repairs. However, this created inherently flawed grant distribution as homes owned by Black people were more likely to have significantly lower pre-storm values than homes owned by white people. Additionally, income and race are closely tied together because of systemic inequity in accessing methods to increase income such as educational opportunities — meaning, for New Orleans, Black neighborhoods are also more likely to have lower incomes. For people living in areas with a median income of $15,000 or less, research found those homeowners had to cover 30% of their rebuilding costs after Road Home grants. However, in areas where the median income was more than $75,000, homeowners covered 20% of rebuilding costs.

Even in the present day, recent studies show that the federal response to natural disasters varies by race, income and education status. For example, evidence finds that Black disaster survivors are more likely to receive less government support than their white counterparts — even when the amount of damage and loss are the same.

The Solution

We know that the number of natural and weather-related disasters are increasing, particularly for communities in the Deep South. At the same time, we also know the Deep South experiences some of the highest rates of poverty as a result of unequal economic opportunity. When disaster strikes, there are several steps the federal government can take to ensure that even our most vulnerable communities are able to rebuild and recover. These steps include:

- Reducing the number of administrative burdens that impacted property owners, homeowners and renters must face to receive assistance. Administrative burdens, or the hurdles the people must overcome to receive assistance, include poor marketing of available government assistance programs, long application processes that require large amounts of paperwork, and delays between application submission and approval. Following a disaster such as Katrina, time is of the utmost importance, and ensuring the prompt flow of resources to impacted communities will expedite rebuilding efforts.

- Increase the amount of natural disaster aid to rebuild and consider individual need, in addition to property value, in the calculation of grant award amounts. As demonstrated during Katrina, when individual need is not accounted for in the grant formula calculation, it will lead to inequitable recovery efforts — particularly for communities with lower incomes and other historically marginalized communities.

Indeed, August 2025 marks the 20-year anniversary of Katrina’s impact on communities and families across the Deep South, and while we cannot change the past, we can honor those most impacted by preparing for the future. Since Katrina, several more hurricanes have hit the Deep South, and we know that there will be more in the future. Investing in disaster response will save lives and help communities focus on rebuilding a better tomorrow.

How to effect change?

- Center the experiences, leadership, needs, policy agenda, and collective voice of directly impacted individuals when developing administrative or legislative policies at the local, state and national levels.

- Invest in community-based services to safeguard the dignity and human rights of vulnerable communities.

Gina Thompson is a policy analyst on the SPLC’s Policy team.

Illustration by Tara Anand.