The U.S. wholly failed to provide these protections in the aftermath of Katrina, especially with respect to Black communities.”

Hurricane Katrina, like other climate-related disasters, raises a host of issues that are addressed by international human rights laws and standards. These laws and standards, including relevant treaties and the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, provide substantial guidance for nations trying to navigate disaster preparedness and response in ways that uphold the humanity of everyone affected. The United States has wholly failed to heed that guidance.

Despite having played a key role in the establishment of the United Nations and the drafting of its first human rights instrument, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United States has only ratified three of the nine core human rights treaties overseen by the U.N. The ratified treaties include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), and the Convention Against Torture (CAT). The treaties that remain unratified include those that address the rights of children, women, people with disabilities, and migrants. Sadly, even those treaties that were ratified more than 30 years ago have largely gone unimplemented, leaving those impacted by natural disasters — and many others — without protections the U.S. promised to provide. When the U.S. ratified these treaties, it declared them to be non-self-executing, meaning that in order for them to have the force of law, Congress would need to pass implementing legislation — which has hardly happened. This means that the rights and obligations declared in these treaties can’t be enforced by U.S. courts.

In the absence of the necessary legislation, human rights treaties could still be implemented in U.S. domestic policy by the White House. But these treaties have also been mostly ignored by successive presidential administrations. No U.S. president has required that any of these treaties be incorporated in or implemented through domestic policy or the work of administrative agencies. For the U.S., human rights are largely seen as a foreign policy issue, and concerns about U.N. treaties are matters for the State Department to address to other nations. Human rights obligations for thee, but not for me.

Living in the Wake: The Enduring Legacy of Hurricane Katrina is a series of essays that examine what the failures of the past can teach leaders about creating the kinds of inclusive, forward-thinking policies New Orleans needs to transform communities that have endured decades of neglect. Read all the essays.

So it should come as no surprise that, although the U.S. government has joined other nations in reaffirming the Guiding Principles since their 1998 adoption and has broadly called for “wider international recognition of the U.N. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement,” it, to date, has not acknowledged their applicability to people displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

The human rights obligations undertaken by the U.S. in relation to natural disasters start with this — the right to life, as recognized by Article 6 of the ICCPR. The U.N. Human Rights Committee, which oversees compliance with that treaty, has recognized that a nation’s obligation to protect, respect and fulfill the right to life includes a duty to develop effective “disaster management plans designed to increase preparedness and address natural and man-made disasters that may adversely affect enjoyment of the right to life, such as hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes” and other disasters. More than half of those who died in Louisiana during Hurricane Katrina were Black, a disparity that likely stems from U.S. failure to comply with this obligation, generally, but particularly in a nondiscriminatory way. Such disparities also appear in the longer term, as research shows that tropical cyclones like hurricanes contribute to excess deaths for years after the storm and that Black people continue to die at higher rates.

U.N. treaty bodies reviewing U.S. compliance with human rights treaties have expressly recognized violations of human rights in the response to Hurricane Katrina. In 2008, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination raised the “disparate impact this natural disaster continues to have on low-income African American residents, many of whom continue to be displaced after more than two years after the hurricane.” It called on the U.S. to increase efforts to return people to their homes where possible, or to otherwise ensure adequate and affordable housing, and to ensure “genuine consultation and participation of persons displaced by Hurricane Katrina in the design and implementation of all decisions affecting them.”

In 2006, the Human Rights Committee expressed concern “that the poor, and in particular African-Americans, were disadvantaged by the rescue and evacuation plans implemented when Hurricane Katrina hit the United States, and continue to be disadvantaged under the reconstruction plans.” It recommended that the U.S. review its practices and policies to ensure the protection of the right to life and the prohibition of discrimination and implementation of the Guiding Principles, and “increase its efforts to ensure that the rights of the poor, and in particular African-Americans, are fully taken into consideration” in recovery plans. At a review in 2023, the committee expressed regret about a lack of information from the U.S. indicating that it had adopted such an approach “to protect persons, including the most vulnerable, from the negative impacts of climate change and natural disasters,” and again recommended that it do so.

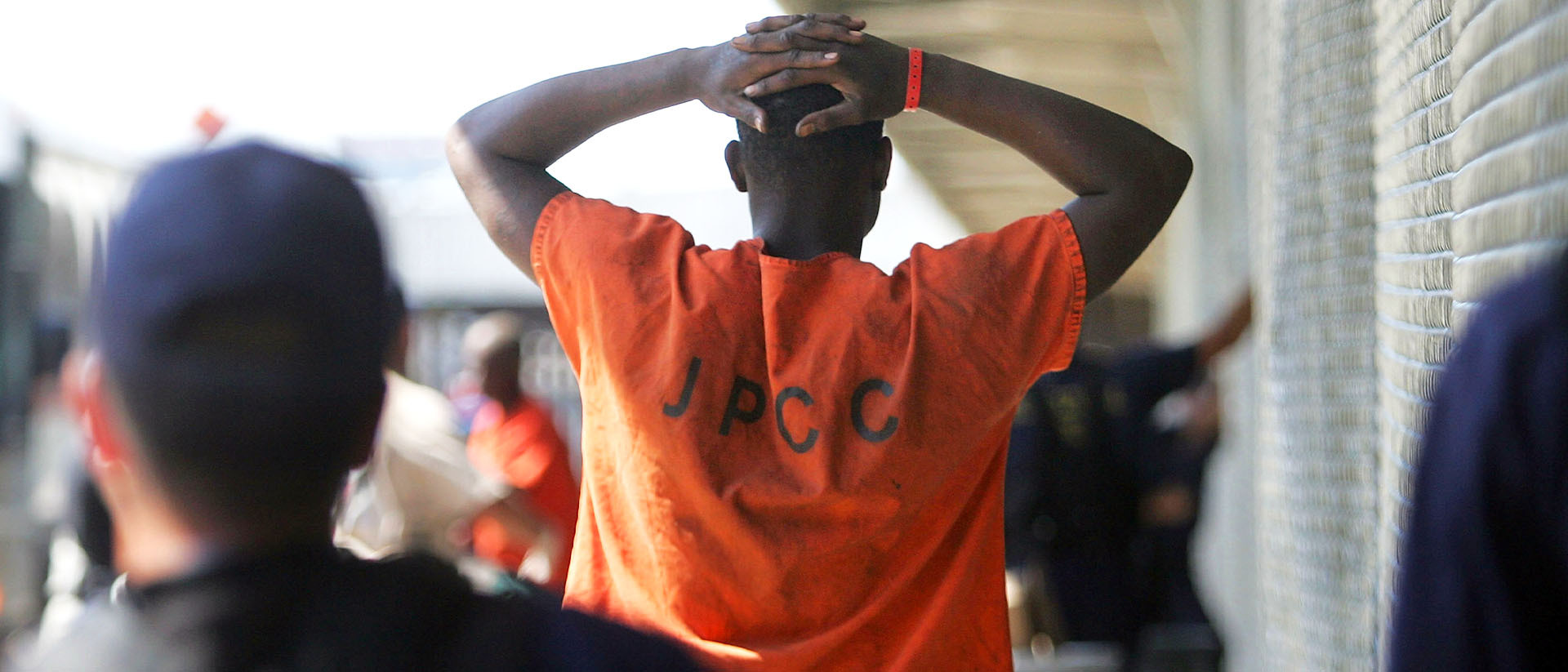

Beyond the very basic human right to life, which the U.S. must respect, protect and fulfill, is its duty to adhere to the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. The Guiding Principles provide that “at the minimum, regardless of the circumstances, and without discrimination,” the responsible authorities “shall” provide displaced persons with food, water, safe and basic shelter, clothing, medical care and sanitation” (Principle 18). In addition, the government is obligated to protect displaced persons, their property, and possessions from a host of threats and abuses (Principles 2, 21, 22). The U.S. wholly failed to provide these protections in the aftermath of Katrina, especially with respect to Black communities. People in those communities faced homelessness or were provided inadequate and toxic trailers as shelter, experienced rampant violence, lacked food and clean water, and were deprived of their properties through a series of bad decisions and policies by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). It also failed to uphold its responsibility to help displaced people return to their homes safely and with dignity (Principle 28).

The U.S. is also obligated under the ICERD not just to condemn and eliminate racial discrimination generally, but to implement “effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists” (Article 2(1)(c)). However, two decades after Katrina disproportionately devastated Black and Indigenous communities in Louisiana, while U.S. policies perpetuated and deepened that devastation, not much has changed. A 2022 analysis by the Center for American Progress of U.S. response to more recent natural disasters found that FEMA “provides help that systematically benefits white victims more than it benefits survivors of color.” A 2023 study found that Black communities in the Southeast are concentrated in areas that are especially vulnerable to extreme weather and are almost twice as likely as other U.S. communities to lie in the path of a hurricane. Following two major hurricanes in 2024 — Helene and Milton — the Kaiser Family Foundation again reported that the racial disparities that led to more severe and lasting impacts for Black communities following Katrina persisted.

The deep racial disparities that lead to dramatically worse outcomes for Black, Brown, and Indigenous people and communities during times of natural disaster begin long before the disaster occurs. In Southern states, including Louisiana, Black and other communities of color are much more likely to live in poverty, and in areas with insecure and substandard housing. Their communities are also far more likely to be located in areas that are most vulnerable to the worst damage from natural disasters like hurricanes, such as areas prone to severe flooding. And they are least likely to have the resources necessary to evacuate or protect themselves. All of these conditions violate the requirements of the ICERD.

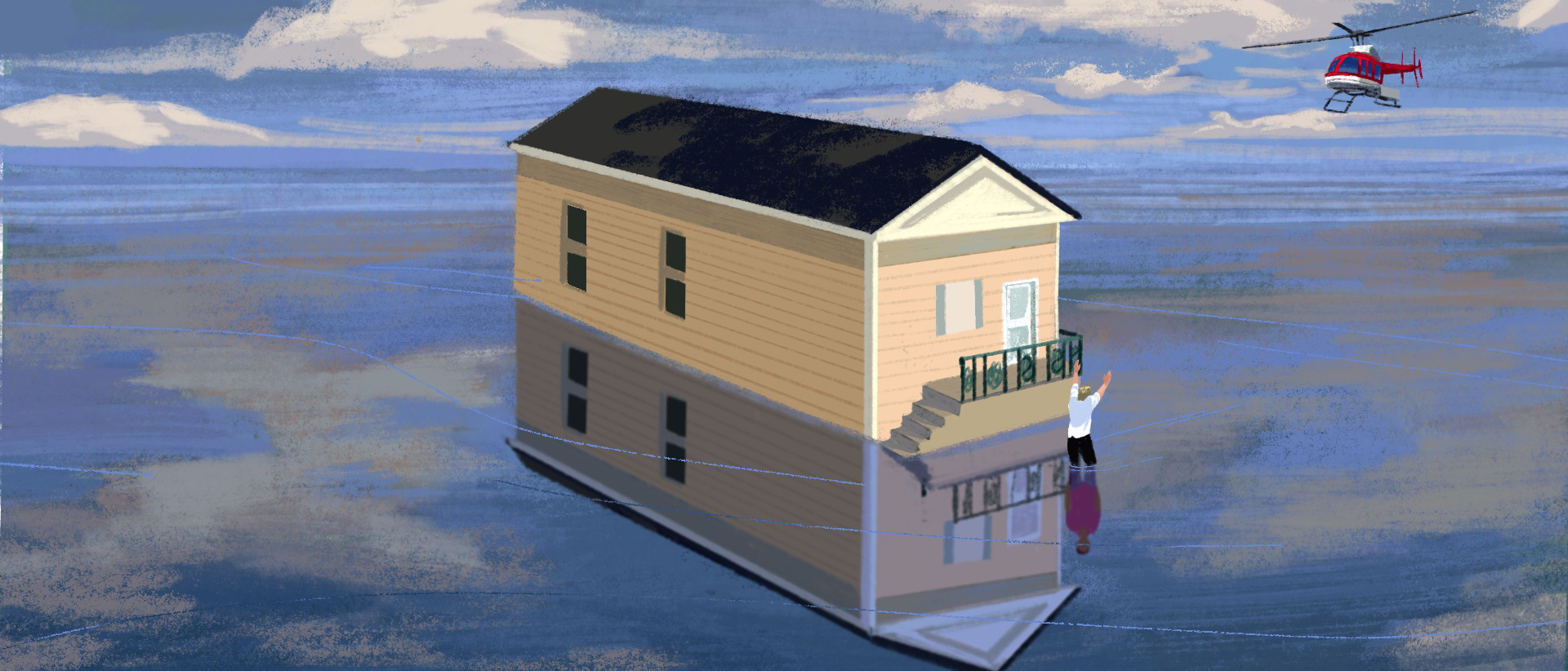

What would genuine compliance with these human rights obligations look like? Such compliance would also begin long before a hurricane or other natural disaster arrives. First, the U.S. would devote substantial resources to identifying the communities that are especially vulnerable to hurricanes and other natural disasters — largely low-income communities and communities of color — and invest in their safety and preparedness well in advance. It would do this by addressing deficiencies in infrastructure like levees and other flood barriers, assisting in ensuring resilient housing, and preparing effective evacuation procedures and the resources necessary to enable people to evacuate, taking into account the needs of the elderly, people with disabilities, and non-English speakers. And it would do all this collaboratively with those communities, closely consulting with them to develop plans that best address their needs. When a hurricane threatens a vulnerable community, the government would work to help ensure preparedness and the ability to evacuate if necessary. Following the storm, the government would assess where the greatest needs exist, and focus its resources on providing assistance. This is not just humanitarian assistance like food, water, medical care, and safe, adequate temporary housing, but with durable, long-term recovery. The Guiding Principles emphasize the government’s duty to establish conditions that allow people to safely return to their homes, and to assist them in recovering, to the extent possible, their property and possessions (Principles 28 and 29).

Contrary to the Trump administration’s insistence that state and local governments should shoulder primary responsibility for emergency preparedness, the U.N.’s Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement recognize that “national authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to provide protection and humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons” (Principle 3). The Guiding Principles also state that the principles are to be “applied without discrimination of any kind” (Principle 4). While U.S. disaster response laws and policies have never sufficiently accounted for the racially discriminatory disparities that make communities of color more vulnerable to and in need of greater resources to recover from natural disasters, the Trump administration’s current review of emergency preparedness policies seems likely to worsen the problem, given the administration’s broad-based attack on any effort to address racial inequalities.

While it is clear that existing human rights obligations do apply to the protection of people who are vulnerable to or impacted by natural disasters, existing international human rights treaties don’t expressly discuss disaster preparedness or response. However, more explicit protections are taking shape. In 2016, the International Law Commission published Draft Articles on the Protection of Persons in the Event of Disasters. The Draft Articles provide, among other things, that “persons affected by disasters are entitled to the respect for and protection of their human rights in accordance with international law” (Article 5), and that “response to disasters shall take place in accordance with the principles of humanity, neutrality and impartiality, and on the basis of non-discrimination, while taking into account the needs of the particularly vulnerable” (Article 6). In December 2024, the U.N. General Assembly adopted, by consensus, a resolution deciding to create a treaty based on the Draft Articles. Whether the U.S. will sign and ratify the eventual treaty is very uncertain. Even more uncertain is whether the U.S. would ever truly comply with such a treaty, or simply seek to use it to put pressure on other nations.

How to effect change?

- Center the experiences, leadership, needs, policy agenda, and collective voice of directly impacted individuals when developing administrative or legislative policies at the local, state and national levels.

- Invest in community-based services to safeguard the dignity and human rights of vulnerable communities.

Lisa Borden is the SPLC’s deputy director of Federal Policy.

Image at top: In an undated photo, Quintella Williams feeds her 9-day-old baby girl, Akea, outside the Superdome in New Orleans as they await evacuation from the flooded city in the wake of Katrina. (Credit: Michael Appleton/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)