“The media brought a white gaze to our neighborhoods. Their interpretation of who the people were was a huge misfire based on a long-term disengagement with Black media.”

— Rachel Breunlin, professor of anthropology at University of New Orleans

Twenty years after floodwaters from Hurricane Katrina inundated the low-lying areas of New Orleans, where most of the city’s Black residents lived, it’s apparent that white-dominated national media outlets and local police dehumanized and misrepresented Black survivors in the storm’s aftermath.

The photographs and videos taken after Aug. 29, 2005, when the storm made landfall, together with news reports on the storm’s impacts, showed brutal truths to the public about humanity’s woes. Journalists printed falsehoods and racist stereotypes about Black survivors, shaping public opinion for years to come.

That reporting portrayed Black residents as looters and rapists, but it depicted white people as desperate victims driven to feed their families any way they could. Reports stoked fear and contempt among white residents who believed that Black marauders were coming to steal their property, leading white vigilantes to shoot Black survivors who tried to escape the floodwaters by taking a route that ran through white neighborhoods.

National media largely looked the other way — or didn’t look at all — as New Orleans police officers killed five people, in at least 11 shootings immediately after Katrina hit the city. Some 900 bodies from Katrina and its aftermath eventually came into an emergency morgue the city set up to handle the influx. The city coroner later said he’d simply chosen not to autopsy some 25 to 50 corpses out of the total and did little investigation into the deaths of the people killed by police. In a police killing and cover-up of a Black man named Henry Glover, the coroner reached a highly dubious conclusion — deciding to not fill out the cause of death on the autopsy, rather than listing homicide as the cause.

“The narrative that locals had run wild and misbehaved was just so wrong when the story was more complicated,” said investigative journalist A.C. Thompson, who, with backing from the national investigative news outlet ProPublica, began investigating the police shootings in 2008.

In the video: Journalist A.C. Thompson discusses lessons learned from media coverage in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. (Credit: Good Land Media)

“The people who contributed to the chaos were the people in power — Mayor Ray Nagin and Eddie Compass, the police superintendent, who scared the population and stirred a sense of fear and chaos, and the police [who] treated Black people with contempt,” Thompson said.

As we look back at the flawed, prejudicial media coverage on this 20th anniversary of one of the worst storms in U.S. history, it raises the question: If the media covered a Katrina-like disaster today, would it make the same mistakes?

Among journalists surveyed in 2023, only about 6% were Black, barely more than the 5.4% of Black journalists surveyed in 2004 when Black New Orleanians made up 67% of residents and 76% of flood victims.

Police officers who kill Black people without cause remain unlikely to be convicted in on-duty shootings even when there is documentary video evidence, according to numerous national studies.

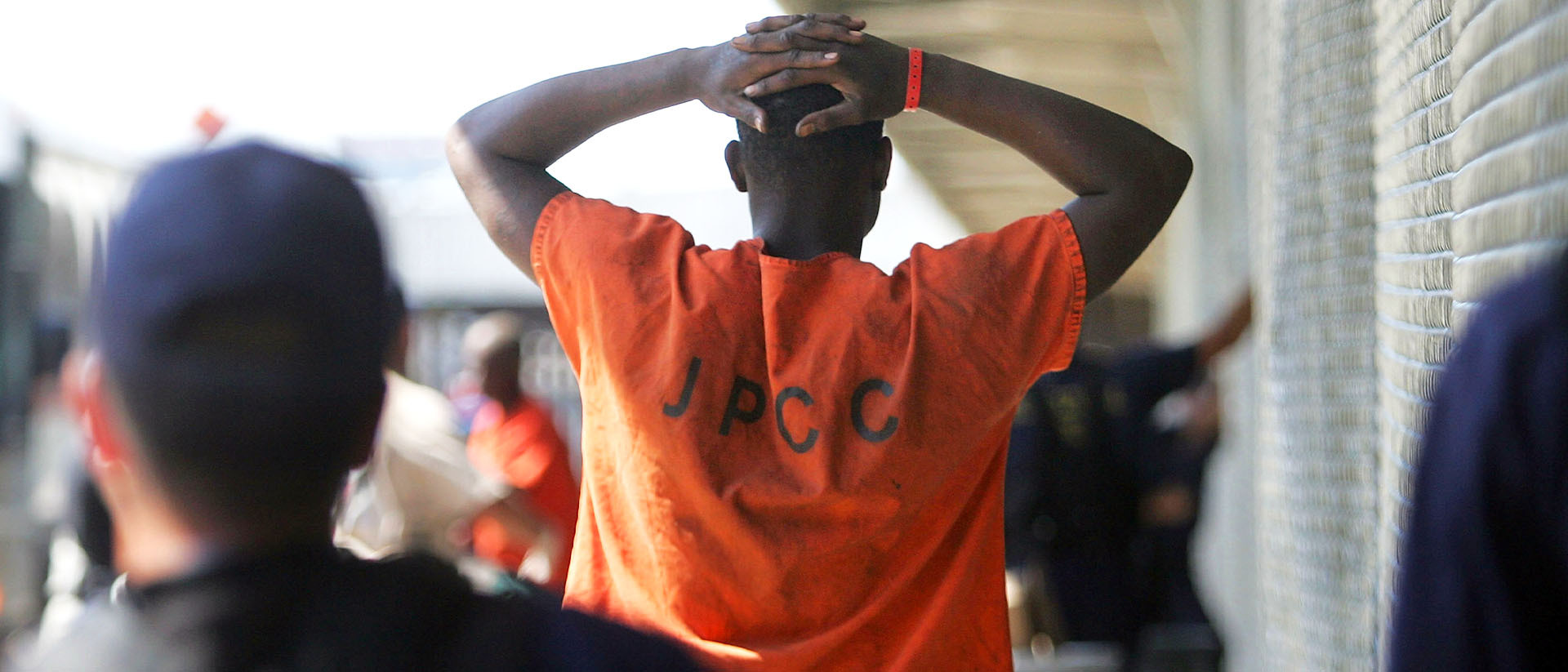

Mug shots of arrested Black people overshadow images of Black communities’ good deeds, accomplishments and leadership roles, although The Times-Picayune has stopped reprinting generic racial descriptions in its crime blotter reports and other outlets discontinued the practice of publishing mug shots entirely.

“I don’t think news coverage today is any better or worse,” said Derwyn Bunton, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s chief legal officer since 2022. In 2005, the California native was associate director at the former Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, now part of the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights. At the time, Bunton was finishing a legal monitoring settlement with the state that reduced the number of incarcerated youth between 1998 and 2005 from more than 2,000 to fewer than 350.

“Fox, CBS, NBC, all the affiliates are dominated by editors who are not in Black communities,” Bunton said. “The coverage that still dominates is largely showing Black and Brown people in the worst light but not white folks, or not as often.”

Living in the Wake: The Enduring Legacy of Hurricane Katrina is a series of essays that examine what the failures of the past can teach leaders about creating the kinds of inclusive, forward-thinking policies New Orleans needs to transform communities that have endured decades of neglect. Read all the essays.

The Trump administration’s war on public and private hiring and content diversity does not bode well for newsrooms’ accurate reporting of Black communities. The president has attacked the U.S. news media with lawsuits against ABC, CBS and CNN, to name a few, accusing the networks of left-leaning bias and unfavorable reporting of him. Congress has cut funding for PBS and NPR member stations, platforms that the White House said “spread radical, woke propaganda disguised as ‘news.’” He withdrew the The Associated Press’ access to White House events in a case that is ongoing, and later revoked access for reporters from The Wall Street Journal.

At CBS, the executive producer at 60 Minutes quit publicly, accusing corporate parent, Paramount Global, of interference in editorial decisions. This came amid President Donald Trump’s lawsuit against Paramount Global, which sought an $8 billion merger with Skydance Media and required federal approval. Trump sued over a 60 Minutes interview with his 2024 presidential campaign opponent, then-Vice President Kamala Harris.

The head of CBS News, Wendy McMahon, submitted her resignation after Paramount Global co-CEO George Cheeks asked for it. McMahon cited disagreement with the company’s direction in a memo about her departure.

What’s more, the recently announced cancellation of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, which is also broadcast on CBS, has been met with allegations that the decision was made to appease the president, a frequent subject of Colbert’s jokes, as well as retribution for the host’s skewering of Paramount Global’s $16 million settlement of Trump’s lawsuit.

Amid this media landscape, any trend toward more equitable reporting in non-white communities appears to be unlikely.

Post-Katrina news coverage

More than 1,800 people died in New Orleans and along the Gulf Coast during and in the immediate aftermath of the storm. The lack of local official evacuation plans and slow, inadequate state and federal responses left the largely Black population that was either disabled, impoverished, too sick or too old to evacuate vulnerable to the worst effects of the storm and subsequent flooding.

The accumulation of these circumstances produced steady media coverage for more than a decade. To date, the drastic decline in the city’s population remains fodder for many a news story. Over half of New Orleans’ population left after the storm, and the city’s population remains considerably lower than it was pre-Katrina.

Empathy informs truthful, accurate, equitable journalism. The journalist’s bottomless urgency to know the truth drives that. No matter how complex and layered the facts of a story, the journalist must identify and listen without judgment to the human voices that illuminate the story’s truths.

“The police murdered unarmed civilians, their family members spoke out, and they could not get local reporters to listen,” said Jordan Flaherty, a white Southern journalist who lives in New Orleans and wrote contemporaneous stories about the struggle for a just rebuilding after Katrina.

Flaherty wrote about his post-Katrina experience, including an area where at least 90% of the thousands waiting to be evacuated by bus were Black. He reported that the National Guard and state police kept armed guard, and he witnessed soldiers pointing guns at children. He won an award for his reporting on the 7,000 people incarcerated at Orleans Parish Prison, where jail staff abandoned their posts, leaving them in rising floodwaters without food, water, electricity or working bathrooms.

Noting that The Times-Picayune’s editorial staff was mostly white throughout its history, including when Katrina hit, Flaherty said reports on police violence against Black New Orleanians have historically appeared in Black-owned newspapers like The Louisiana Weekly, but the stories of post-Katrina police violence did not draw national attention until Thompson’s investigative reporting broke through.

“If The Times-Picayune reports on crimes committed by the police, they risk losing access. When you don’t have media that represents a community, you’ll have blind spots,” Flaherty said. “[The Times-Picayune] got a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage while it ignored the biggest story in the city at that time, which was police and vigilante violence against Black New Orleanians.” As an example, he mentioned Alex Brandon, then a photographer for The Times-Picayune. Brandon later testified in the Glover trial that he knew details about the police killings that he didn’t reveal.

Prejudicial imagery

Among the most upsetting images after the hurricane showed thousands of desperate Black residents from the city’s flooded downtown and eastern areas trying to cross the Crescent City Connection bridge on foot to reach the dry west bank of the Mississippi River. They found police vehicles blocking the bridge exit, officers with weapons drawn and blaring through bullhorns a warning: “Turn back. There is nothing for you here,” said Bunton, remembering the reports.

Photos taken on the bridge, another one showing the lifeless body of a Black person in a wheelchair hidden beneath a blanket in front of the Louisiana Superdome, and a Time magazine cover photograph of a Black woman struggling to push an elderly woman in a wheelchair through high floodwaters remain potent symbols of Black desperation after Katrina struck.

“These images triggered me because they reminded me of the injustice poor Black and Brown people suffered from white institutions and made me really angry and sad at the same time,” Bunton said. “Someone was waiting for help and had simply died,” he said, referring to the woman who died in her wheelchair.

On Aug. 28, 2005, the mayor of New Orleans opened the Louisiana Superdome as a shelter of last resort. Over the course of three days, the number of people inside — including National Guard soldiers — rose to 30,000 or more. Absent air conditioning, food, sanitized water, electricity, working bathrooms and medical care, conditions were abysmal.

“Folks at the Superdome were almost entirely Black, and the lack of [government] response made it seem like Black folks were left on their own,” Bunton recalled. “It was one of those moments that really showed the disparate treatment of Black people. I remember Brian Williams appearing on The Tonight Show sharing his experiences as someone reporting on the immediate aftermath of Katrina. [Williams] struggled to hold back tears and with his voice cracking said, ‘If this were Beverly Hills, this wouldn’t be happening.’”

Rachel Breunlin’s frustration with media coverage also lingers. She said she believes that reporting on Hurricane Katrina’s devastation showed a complete misrepresentation of the city’s Black communities. In 2004, the University of New Orleans anthropology professor co-founded the Neighborhood Story Project, a public ethnology project to showcase the voices of the city’s Black youth.

The police murdered unarmed civilians, their family members spoke out, and they could not get local reporters to listen.”

— Jordan Flaherty, journalist

The project’s first set of books authored by high school students began shortly before Katrina. The year after the storm, the organization published Coming Out the Door for the Ninth Ward, which was written by members of the Nine Times Social and Pleasure Club. Hundreds of lives were lost in the mostly Black Lower Ninth Ward due to devastating flooding, but band members extolled the ward’s unique culture of parading, arts and music and described how they were rebuilding their lives after Katrina.

“The media brought a white gaze to our neighborhoods,” Breunlin said. “Their interpretation of who the people were was a huge misfire based on a long-term disengagement with Black media. They assumed that Blackness meant they didn’t have resources, or that Black people didn’t own their homes. If people were Black, if they were on their rooftop, or walking on overpasses trying to get out of the city, they were assumed to be poor.

“But New Orleans is much more complex, intense and vibrant than the media depicted,” Breunlin continued. “The Time magazine front cover showed a moment of desperation, but the people themselves weren’t taking that as a permanent identity for themselves. The media brought unconscious racial and economic assumptions [to reporting]. They assumed criminality and reported on looting and violence.”

National media ignored police violence

Police violence toward the Black community in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina might never have reached a national audience had not Thompson understood that closure for the victims and their families comes from finding justice.

Thompson wrote or co-wrote over 40 stories between December 2008 and December 2010, with later, additional support from the national investigative journalism news program Frontline and reporters from The Times-Picayune, who had in large part ridden out the storm and been covering the city throughout the first two years of recovery. All told, the team produced 81 written pieces, according to Thompson.

Simultaneously, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) was leading a civil rights investigation into the New Orleans Police Department, which resulted in a 2012 DOJ consent decree under which the department committed to reforms. That investigation, along with additional criminal cases, came after the 2005 resignation of Compass — the police superintendent — and the firing of 60 police officers for their desertion during Katrina. Subsequent trial decisions disproved the media myth that Black New Orleanians had subjected the city to a violent crime spree in Katrina’s aftermath.

Mulling the question of whether news outlets today would investigate rampant police violence and cover-ups, one would like to hope that social media coverage would force news outlets to investigate.

But shareholder profits are even more influential on newsrooms than they were in 2005, and most media companies have drastically cut editorial staff and gutted investigative reporting teams as they rein in expenses. The strict partisanship and balkanization of news over the past 15 years ended “democratic” news coverage, the kind of widely accepted, general reporting that journalism icons Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley and Barbara Walters delivered nightly to the American public. Nowadays, corporate owners are apt to interfere with editorial direction in support of one political perspective over another, as demonstrated in The Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos’ decision to revamp the paper’s opinion pages in favor of “personal liberties and free markets” instead of the previously wide range of viewpoints the publication had offered.

This open partisanship trades honest human voices for a company line. It sells out the greater good.

Rhonda Sonnenberg is a senior staff writer for the SPLC.

Image at top: A boarded-up storefront in New Orleans’ French Quarter is pictured on Nov. 14, 2005, nearly three months after Katrina made landfall. (Credit: Benjamin Lowy/Getty Images)