Power has three faces. The first face — we see who won and who lost. The second face: who decides. To figure that out, you must ask who is benefiting and who is losing: the third face. This is when the deep structural contours of power emerge.”

— Marshall Ganz on Steven Lukes’ “three faces of power”

Recovery for whom? This is the critical question we must ask when we deliberate about how to ensure that recovery efforts are lasting. For recovery to occur and be sustained, it requires adequate social, economic and political structures that serve the interests of the population seeking recovery. When recovery for those experiencing injustice is sought, a restructuring of the systems of control must follow. It is because of the oppression of these systems that recovery is usually necessary. In cases of uncontrollable disasters, these systems are exacerbated, requiring recovery from the current injustices and the immediate disaster, as witnessed by the impact of Hurricane Katrina and the COVID-19 pandemic on Black and Brown communities.

Understanding Political Power

If recovery requires restructuring, then restructuring requires political power. The problem is that the needs and interests of Black and Brown communities have been historically neglected; these communities have not historically controlled political power in the United States.

Understanding why and how to control power can be effective to challenge and dismantle the status quo that doesn’t work for everyone, and in its place build systems and institutions that will positively affect our daily lives.

We must know this about power: It is relative, pluralistic, and not beholden to any one group. Power can be shifted and controlled at its sources. Power depends on the collective for reinforcement of its sources. Political power emerges from the interaction of some or all these sources: the perception of those in control as the superior authority, the groups that cooperate in maintaining the superiority of authority and their abilities to do so, the level of obedience and submission by the collective, the access to and control of resources by the authority, and the extent to which obedience is reinforced by the authority.

In the video: Jalaya Liles Dunn, director of Learning for Justice, discusses her work with the Children’s Defense Fund in New Orleans post-Hurricane Katrina. (Credit: Myisa Plancq-Graham)

The ebbs and flows of history show us how oppressed groups have shifted power to advance our civil and human rights. The challenge of our time is who will control the political power so democracy is fully realized and all our humanity is fully recovered.

Historical Context of Recovery and Reconstruction

Our country’s first attempt at recovery following the Civil War and the abolishment of slavery was during Reconstruction (1865-1877). This period of recovery was intended to restructure the United States into a multiracial democracy and reinstate the union of the states. However, the interests of recovery for the Confederate states contrasted significantly with those of the 4 million newly freed Black people. While white citizens in the Southern states sought restoration of their power and control after the Confederate defeat in the war, the interests of the emancipated population focused on their recovery post-slavery. For Black Americans, recovery was about how they would participate as meaningful citizens in the democracy and become integrated into the political, social and economic life of the country. But for this type of recovery to occur, the political infrastructure of the country had to be reconstructed.

Living in the Wake: The Enduring Legacy of Hurricane Katrina is a series of essays that examine what the failures of the past can teach leaders about creating the kinds of inclusive, forward-thinking policies New Orleans needs to transform communities that have endured decades of neglect. Read all the essays.

The recovery process began with the competing interests of the two groups. Control of the “Reconstruction policy” would determine who controlled political power and would chart the course of the nearly 100-year-old democracy. Presidential control of the policy favored the interests of the rebel Southern states and focused on restoring political power to white Southerners through the creation of Black codes — laws designed to maintain the status quo of a white supremacy system through racial repression.

Congressional control of the Reconstruction policy — which became known as radical reconstruction — involved the federal government’s direct intervention to protect emancipated Black Americans and ensure their place in all aspects of democracy. Constitutional amendments (the 13th, 14th and 15th “Reconstruction amendments”) and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 followed to protect Black people as they made a life after the system of slavery. Black political leaders were elected to represent the interests of emancipated Black Americans, and Black people organized to establish schools and churches. Importantly, Black people mobilized and led Black conventions to outline a political agenda inclusive of their interests as citizens. This was a radical approach and was met with hostile opposition.

The Reconstruction period eventually ended when Southern Democrats and allies of President Hayes settled in the Compromise of 1877, which included the federal government’s retreat from enforcing protections for Black Americans. A period of regression followed in which voting and civil rights for Black people were reversed and white supremacy was restored. Control of power for recovery in the Southern states remained in the hands of white citizens, and the failed promise of Reconstruction led to a “nationwide system of racial control and second-class citizenship … to deny political, social and economic equality to Black people.”

Recovery in New Orleans: Who Decides, Who Benefits, Who Loses?

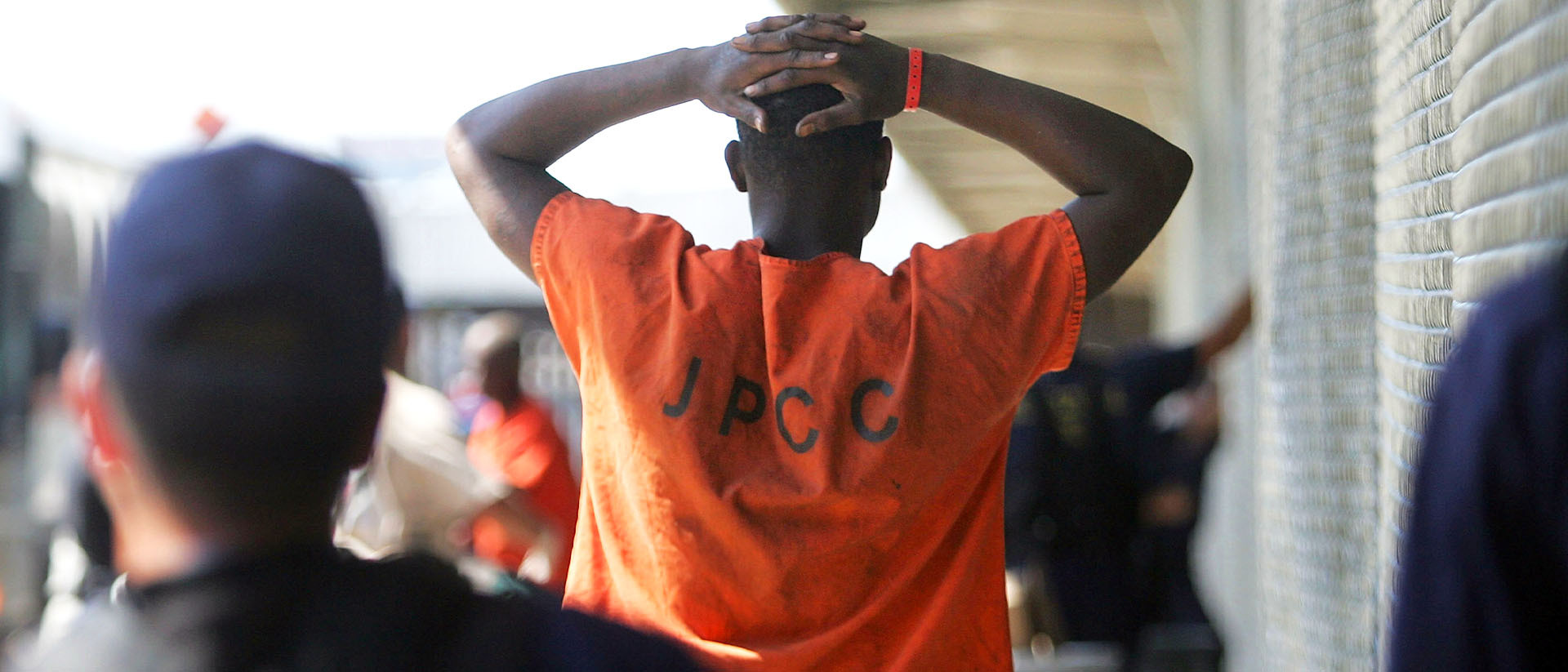

Recovery always offers opportunity for tremendous change. In 2025 — 160 years after our first commitment to recovery for newly emancipated Black people — we find ourselves reflecting on the recovery of New Orleans 20 years after Hurricane Katrina. Physical recovery from the storm is absolutely a critical piece of the dialogue. But more importantly, dialogue around the recovery of culture; political power; and economic, environmental, education and criminal justice should be centered. Twenty years later we are long overdue for a radical period of reconstruction. History has demonstrated that recovery for Black communities and communities of color will not be fully realized through our current structures of political power. In the words of journalist Vann Newkirk, “A system cannot fail those it was never meant to protect.”

From 2006-2007, shortly after Hurricane Katrina, I was in New Orleans to set up Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) Freedom Schools program sites. The CDF’s cross-department initiative included the CDF Freedom Schools and CDF Southern Regional Office (SRO) teams to help ensure affected families and their children had a resource to aid in their recovery process and to build new structures of power for meaningful change. Based on the 1964 Freedom Schools model, the CDF Freedom Schools model also centers radical questioning — “to question everything, question everything around you, and not just take information at face value or to consume information without critical thought or critical analysis.”

We were sent to New Orleans by CDF Founder and then-President Marian Wright Edelman to meet the needs of the children and families. On my first day in New Orleans, I arrived at the local YMCA that was still standing amid the storm’s destruction of the surrounding neighborhoods. There had been no immediate cleanup and no programs or placements to ease the trauma for displaced children. While meeting at the Y with a group of students in grades K-8, rain began to fall. The rainfall was nothing out of the ordinary, but students cried in fear, and many parents arrived to pick up their children early from the program. Trauma from Katrina haunted these families and deeply affected their children.

Our time in New Orleans was focused on building support to provide enriching programming for the children in New Orleans; and programming extended to Baton Rouge and Jackson, Mississippi, where many families moved to following the storm. Mrs. Edelman invited “Hollywood moms” to witness the devastation and learn what meaningful recovery looked like. The guest list included Cicely Tyson, Malaak Compton-Rock, LaTanya Richardson Jackson, Holly Robinson Peete and many others. On May 2006, my colleague Robin Sally and I were tasked with completing the setup of an old storefront building into a demonstration CDF Freedom Schools site. The building’s walls were just studs, with no drywall and no electricity. At the last hour, we had to shine the car’s lights through the storefront windows to put up the last signs that would welcome the children from the YMCA, the community, our colleagues and the Hollywood moms the next day.

When we introduced Freedom Schools to New Orleans the following day, Cicely Tyson read aloud to the children. News outlets highlighted the event. After a day of activities, we took the moms on a tour of the reality New Orleans’ families were facing. The tour was led by community members. We witnessed the FEMA trailers. One trailer site was on an old prison yard. Regardless of the location, displaced residents maintained a sense of community. I remember a large old tree serving as the gathering spot for the community in the midst of the devastation and destruction.

After that day in May, resources were allocated to various levels of support. Robin and I stayed in New Orleans and were connected to highly respected and trusted local leader Mary Joseph to set up sites across the area. A moment of community that stands out is Ms. Joseph’s invitation to a barbecue at her home, since we were away from our homes during the July Fourth weekend. At the barbecue, they were waiting for “Ruby” to bring the macaroni and cheese. Much to our surprise, the Ruby who came in with the delicious macaroni and cheese was Ruby Bridges, known for integrating an all-white school in New Orleans in 1960 when she was only 6 years old, and who represented for many of us the image of school desegregation following the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown.

Alongside the strategic planning with local leadership convened by Ms. Joseph, trained servant leaders were deployed to help local leadership set up CDF Freedom Schools sites across Louisiana for ongoing summer and after-school programming. The storefront building in New Orleans was remodeled, and with Ms. Joseph as its director served as the flagship site offering wraparound services for families, children and the larger community. Program sites remained active in the following years, and program partners joined the larger movement for education and justice.

Today, 20 years later, the then-college-aged servant leader interns and school-aged program participants are leading organizations, institutions and program models for meaningful change. They have run for elected office in order to take control of political power to serve the interests of the populations most affected by injustice. The Freedom Schools after Katrina not only provided support for recovery in the wake of devastation but positively affected a generation that is needed at this time for the radical reconstruction we are calling for now.

CDF Freedom Schools demonstrated some of the possibilities of recovery efforts that centered community. Sustainable systems change, however, needs political power that doesn’t simply seek to return to the status quo, because the status quo of systems in the South means continuing racial and economic injustices.

I revisited Louisiana in 2022 on an SPLC Learning for Justice learning tour and had the opportunity to sit with parents from New Orleans and Houma, Louisiana, to discuss the realities of their current education system. At the time, 100% of New Orleans schools were under a public-charter system. The parents I met were outraged by the model that removed their community schools and once again displaced the culture and geography of their neighborhoods. The complete public-charter system was a direct response to the lack of operational schools after Hurricane Katrina. Moving schools from the neighborhoods they serve and taking away complete public control of schools are strategies to weaken the political power of local communities.

The recovery was not about ensuring the children and families of New Orleans received an education to uplift their communities. Instead, recovery of the education system seemed to favor the interest of those benefiting from the status quo. The opportunity for transformation became a tool for control and to further erode power. The schools of Houma are part of the public school system; however, the parents and community shared their concerns regarding the disparities between the poor schools of color and the more affluent white schools. The public schools are further segregated with no equity in resources and funding. Around 75% of students in Louisiana are in public schools, and many of the schools receive Title I funding, indicating a high percentage of low-income students within the schools.

The education system is just one indicator of the effects of recovery in New Orleans and Louisiana 20 years after Hurricane Katrina. Other systems reinforce and are reinforced by an education system not fully controlled by the public, creating an interlocking system of injustices that further repress communities of color.

Our Season for Radical Reconstruction

We are living in an 18th century democracy.”

— Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries

This 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina not only encourages reflection and analysis but also presents an opportunity to rebuild and reconstruct. This is the moment for radical reconstruction — a time to reimagine and refashion what an inclusive, multiracial democracy means for all people and communities. We can no longer let the limitations of an 18th century democracy speak for our futures and generations to follow. We are witnessing in real time how political leaders, their allies and influencers are manipulating how Black and Brown children and families are educated; receive health care, nutrition and employment; and are criminalized by current levers of power. We need a reconstructed democracy that accounts for the realities of communities of color, and expands its scope to a 21st century democracy with the ability to thrive generations beyond us.

Now is the time to talk more intentionally about who controls political power. Whoever controls the power controls whether true recovery happens and if it lasts. A lack of understanding of why and how to control political power among the masses ensures the interests of one group are favored over the interests of others. This is the time for Black and Brown communities across the South — and ultimately the nation — to demand control of power. This cannot be achieved in a single election or event. However, in constant learning, debating, consensus building, deliberation, reflection and action, we can demonstrate how to practice democracy and ultimately restructure it so it meets the needs of our communities.

Black leaders newly emancipated from slavery knew what was at stake and the importance of control and power. They provided us with a legacy and blueprint that we can build from as we contend for our own liberation.

During the period of reconstruction and recovery of their humanity, emancipated Black people demonstrated how to practice and push the scope of a 100-year-old democracy. Here is what we can learn from them as we enter our season of radical reconstruction and refashion the practice of democracy in a soon-to-be 250-year-old democracy.

- Center liberation for all. Build with the spirit of community, cooperation and organization. Defy division, control of others and exclusion.

- Uplift local autonomy and leadership from the community.

- Define your own political agenda. Listen to the needs of the collective. Hold spaces for strategic conversations and public learning.

- Recognize your collective resources. Practice wielding those resources into power.

- Organize bases of democratic power to provide constant models of service and advocacy.

- Lead strategic action. Actions taken should shift power so it benefits the needs of the collective.

- Stay engaged and participate in civic life in all areas. Teach this as a value and prerequisite for being in community.

Let’s be sure to prepare ourselves and new-generation leaders with the understanding and call to action to control and wield power for the rightful recovery of our Black and Brown communities. These communities have faced various forms of destruction and devastation — from life-threatening storms, police violence, a pandemic, and assaults on our public education, health care and criminal legal systems. Martin Luther King Jr. reminds us how power should be used: “Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.”

Frederick Douglass reminds us how we control power: “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

How to effect change?

- Reduce the number of administrative burdens that property owners, homeowners and renters must face to receive disaster recovery assistance.

- Increase the amount of natural disaster aid for rebuilding and consider individual need, in addition to pre-disaster property value, in calculating grant award amounts.

- Address housing affordability and the root causes of homelessness instead of criminalizing people experiencing homelessness.

- Strengthen food security and social safety net programs, as well as investment in programs designed to break the cycle of poverty and economic instability.

Jalaya Liles Dunn is the director of Learning for Justice.

Image at top: Actor Cicely Tyson reads to a group of students at a New Orleans school on May 8, 2006. Tyson and other entertainers were visiting “Freedom School” sites set up by the Children’s Defense Fund in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. (Courtesy of Children’s Defense Fund)