The storm’s impact of displacing thousands of voters depressed voter turnout to 36%, down 10 points from 2002.”

Hurricane Katrina brought devastation to the Gulf Coast, with an estimated 1,392 fatalities, 300,000 homes destroyed, and over a million people displaced. The storm was responsible for over $125 billion in damages and an estimated $2.9 billion in lost wages due to destruction and displacement. After Katrina’s destruction, Louisiana was challenged with how to recover, including how to maintain free and fair elections.

New Orleans municipal elections were initially scheduled for February 2006, just five months after Katrina made landfall. However, these elections would be plagued with problems resulting from the storm. Large swaths of the city had been destroyed and remained so by the time the elections were scheduled. Much of the election infrastructure had been destroyed as well, including polling sites and voting machines. Of New Orleans’ 442 polling places, 295 were destroyed by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. This destruction prompted a decision to delay the election until April 22 of that year.

In the Video: Data and Research Analyst Zach Mahafza discusses the long-term effects that natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina have on reconstruction, highlighting the social cohesion built by an active electorate. (Credit: Myisa Plancq-Graham)

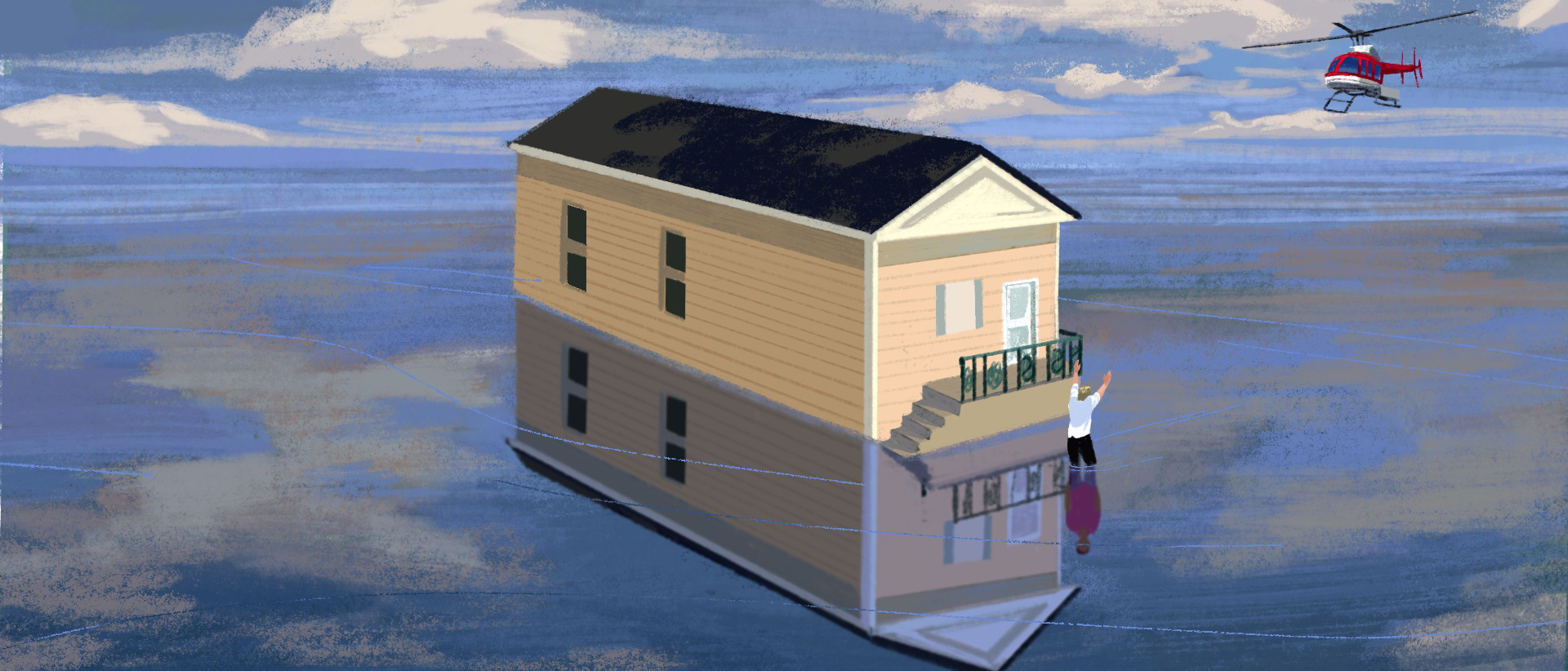

Numerous methods of alternative voting were utilized, including voting by mail and early voting at locations across Louisiana to allow displaced people a means to cast a ballot. Some displaced people were bused in from as far as Atlanta to vote for their next mayor. The storm’s impact of displacing thousands of voters depressed voter turnout to 36%, down 10 points from 2002.

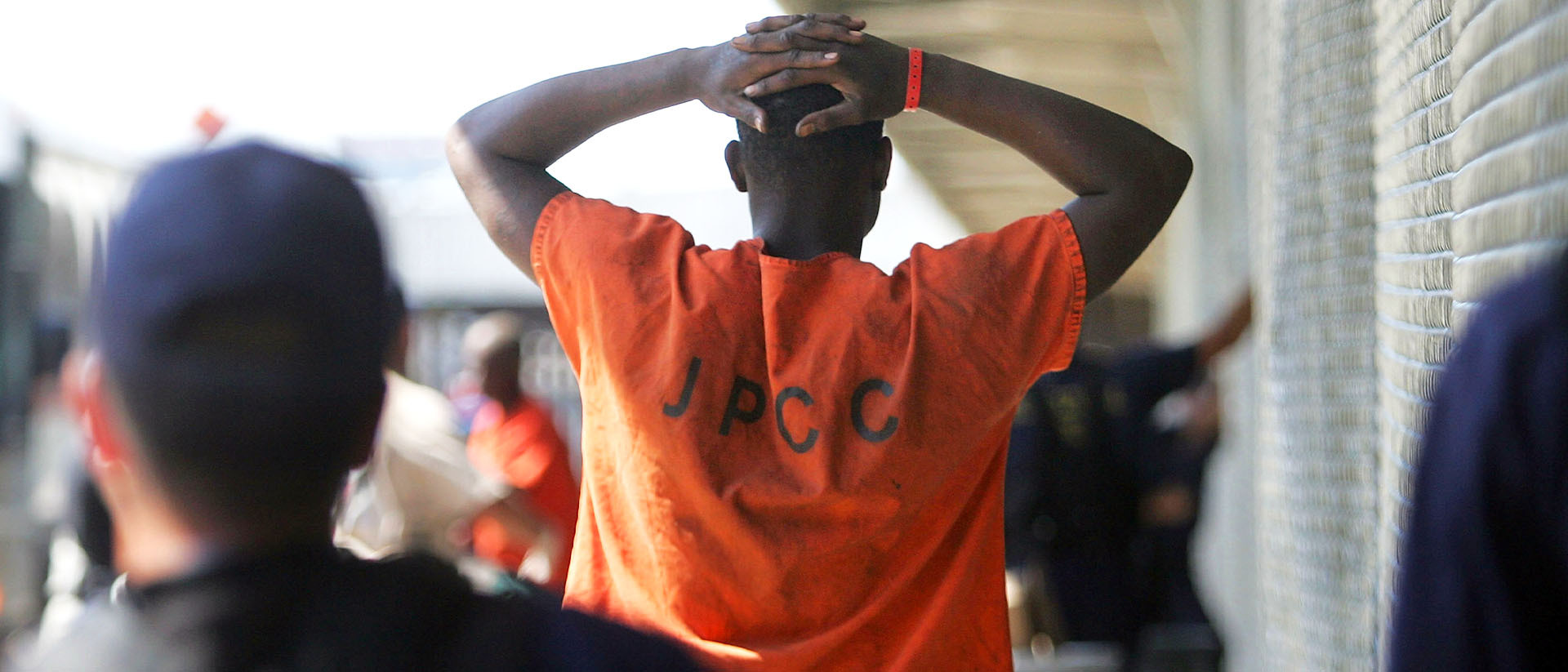

Due to the flood impacting predominantly Black areas of New Orleans and preexisting socioeconomic inequities, Black voters were less able to return to the city and directly participate in the election. This meant displaced populations were even more reliant upon alternative mechanisms to cast their ballots. Because these mechanisms were not sufficiently robust, there was a decrease in voter participation among minority communities. While early and absentee voting was offered, there was confusion over the rules for satellite voting places. This was further exacerbated by FEMA not sharing information with election officials that could have reduced the complications associated with voting by mail for displaced voters.

Living in the Wake: The Enduring Legacy of Hurricane Katrina is a series of essays that examine what the failures of the past can teach leaders about creating the kinds of inclusive, forward-thinking policies New Orleans needs to transform communities that have endured decades of neglect. Read all the essays.

The consequences of these inadequate systems led to significant changes in the Louisiana electorate. The loss of so many Black residents from New Orleans and prioritizing the recovery of predominantly white parts of the city led to significant shifts in the balance of power within the state. Overall, losing Black voting power undercut local political expression and impacted future redistricting, which already faced significant barriers from lingering white supremacist policies kept in check by the Voting Rights Act.

While Katrina itself was notable for the grand scope of its impact, it was by no means the only natural disaster to have harmed the South, nor was it the first hurricane to complicate local elections. In 1965, Hurricane Betsy had a similar impact by flooding predominantly Black neighborhoods, displacing people, and making it difficult to vote. According to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), the number of billion-dollar disasters has averaged 19 per year across the U.S. since 2015, with 27 such disasters happening in 2024. Table 1 shows the number of billion-dollar disasters for Deep South states since 1980, including several disasters that impacted multiple states at once.

Climate change is increasingly impacting people’s lives, and the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are increasing. Because of this, we are seeing new challenges across a variety of economic, social and political systems, including the potential effect on our electoral processes and systems.

The electoral system is woefully underfunded in a variety of areas, but the lack of climate resilience is one area where the underfunding will have significant community impacts should this issue remain unaddressed. As Table 2 suggests, the displacement of over a million adults just in the last year could have an impact on electoral results across the Deep South.

It is also noteworthy that these displacements are across counties of different political leanings, implying that climate resiliency against natural disasters is essentially a nonpartisan issue. According to Rebuild by Design, 99.5% of congressional districts had “at least one federally declared disaster due to extreme weather” between 2011 and 2024, displacing millions of people. The map below of FEMA’s disaster risk index shows the predicted vulnerability each Deep South state faces from natural disasters.

Impacts on the Electoral and Political System

Natural disasters pose a significant threat to participation in the electoral process. A poorly timed storm or fire could destroy someone’s ability to provide necessary documentation to vote, displace populations, or even make going to the polls an unsafe or overly time-intensive process. Disasters that destroy property and displace people will also upend people’s lives, leaving them with little time to participate in the political process, acquire information, or have the time to go to the polls.

This is exceptionally problematic as people displaced or without housing are those most in need of governmental action and support from their elected officials. The lack of resources is further exacerbated by the potential cuts in electoral participation rates. In state or countywide races, areas heavily impacted by natural disasters will have lower voter participation rates, which can easily alter the outcomes of elections. To the extent that the impact on voting rates can impact electoral outcomes, this can lead to years of ramifications across the political sphere and undermine voter will.

Impacts on Social Resilience and Civic Culture

Natural disasters and hazards not only present physical harms and dangers to a community, but their social, economic and psychological impacts can be just as destructive. Polling places are often critical social touchstones within a community. These may include places of worship, recreation centers, schools, libraries, and other important community spaces. The resiliency of these spaces, along with the ability for people to return home, is important for a community’s recovery.

The loss or destruction of iconic landmarks presents an additional risk. This is because communities often rally around or center core elements of their identity around significant events or locations. Thus, the loss of such sites may further hinder the capacity for recovery. This makes it worthwhile to invest in increasing the resilience and durability of such sites, as it can serve to protect areas of social interest and aid with cultural and social healing after major disasters. This also provides a mechanism to help further galvanize other aspects of post-disaster recovery.

Investing in these social spaces to ensure they are resilient will aid in recovery, provide intuitive points for offering resources related to relief, and allow for continued economic development within a community. Such spaces also allow for a sense of community to persist, which has added benefits pertaining to the cultivation of social bonds, decreased social instability, and a community’s sense of place and self. These elements play a critical role in recovery and can help prevent the significant demographic decline that New Orleans saw after Katrina.

What Can Be Done?

Increased spending on infrastructure resilience would be a primary means of action. Instead of prioritizing plans to relocate polling sites and focusing solely on alternative locations and staffing in the event of a disaster, resilience spending could help prevent the problem. A proactive approach to preventing the impacts of natural disasters will be far more productive than a reactive approach.

The National Institute of Building Sciences estimates that every dollar spent on resilience infrastructure results in $6 of savings on average. A variety of funding programs are available for local and state governments to acquire the funding necessary to improve their resilience, such as FEMA’s Safeguarding Tomorrow Revolving Loan Fund and the Department of Defense’s Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration Program (REPI). These programs cover a wide range of infrastructure and community resilience needs, but focusing on places utilized for electoral purposes is not often prioritized in this list.

Realigning some of this spending to prioritize places used as polling sites can help mitigate the potential electoral impacts of natural disasters. Also, emphasizing community spaces, housing, and building codes in minority areas would be beneficial in reducing the chances of displacement by increasingly severe weather. Focusing on community resilience and election infrastructure could increase an applicant’s competitiveness for these programs. FEMA notes that for its Revolving Loan Fund, it is built to “support mitigation projects at the local government level and increase the nation’s resilience to natural hazards.”

However, there are limitations with this approach. Due to the significant degree of uncertainty surrounding the federal budget and spending at the time of this writing, these programs may not be well funded, may refuse to pay, or may not exist within the next few months. Therefore, localities may also need to consider other ways to fund their infrastructure resilience.

A second means of addressing the vulnerability of the electoral system to severe weather is to provide the public with alternative means of access to the ballot. Increasing access to mail-in ballots, online voting, early voting, having disaster plans that include backup polling places or extended times of operation, and other tools of ballot access can significantly reduce the impact that natural disasters have on the electoral process. Also, displaced voters could benefit from similar mechanisms as active-duty military for accessing the ballot or registering for elections. This has been previously considered with the Displaced Citizens Voter Protection Act of 2005 (HR 3734), though this legislation failed to advance to a vote. This could have been beneficial to the displaced New Orleanians forced to bus in from out of state to vote immediately post-Katrina.

Overall, the electoral impacts of Katrina are still felt today, making election resiliency a priority as major storms become more frequent. The population and demographic changes in New Orleans and Louisiana impact minority representation today in the state legislature and Congress — particularly Louisiana’s 2nd Congressional District. More effective means to access the ballot would have helped recovery and preserved a New Orleans community where all people can thrive.

How to effect change?

- Invest more funding in polling sites, precinct officials and election infrastructure, making them more resilient to and nimble during natural disasters.

- Protect democracy by providing voters with extended registration deadlines, adequate notice for postponed elections, and extending absentee and early voting at alternate locations to accommodate residents displaced by weather crises.

Zach Mahafza is a data and research analyst for the SPLC’s Legal department.

Image at top: In a photo from April 22, 2006, a sign on Tennessee Street in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward informs voters of their new polling location. (Credit: Alex Brandon/Associated Press)