The areas damaged by Hurricane Katrina generally had higher percentages of Black residents, higher percentages of renter households, and higher poverty rates compared to undamaged areas.”

Disasters do not discriminate. Or do they?

Storms do not make landfall with animus, nor do they decide to strike certain communities because of bias. However, our ability to prepare for, withstand and recover from disasters is impacted by ongoing inequities in our communities.

How we experience disasters is not natural in any way; it is fundamentally social and political. In the case of Hurricane Katrina, there was flooding across 80% of New Orleans. There is no question that this storm was highly impactful across the Gulf Coast. It was one of the most destructive storms in U.S. history, causing the largest displacement of people — well over a million from across the region — due to a climate event since the Dust Bowl migrations of the 1930s.

And then Hurricane Rita, the strongest storm ever recorded in the Gulf of Mexico, struck less than a month after Hurricane Katrina. It reflooded parts of New Orleans’ Ninth Ward, and nearby St. Bernard and Cameron Parishes.

But the truth is, we are not all impacted the same way by disasters. Our communities are not equitable and inclusive, and therefore are not similarly situated in terms of our risk and resilience. What unfolded in Louisiana in the following weeks, months and years is in many ways both unique due to the scale, scope and history of the region, and also typical of how communities are impacted by such disasters. Disasters reveal inequities that already exist, reinforcing and replicating inequality as we face the long road to recovery.

Living in the Wake: The Enduring Legacy of Hurricane Katrina is a series of essays that examine what the failures of the past can teach leaders about creating the kinds of inclusive, forward-thinking policies New Orleans needs to transform communities that have endured decades of neglect. Read all the essays.

In a disaster, those who have access to more resources tend to fare better. But also, due to disparities in the way in which disaster aid is distributed, white families tend to be better off after disasters, but Black families tend to be worse off.

Researchers from Rice University and the University of Pittsburgh found that in counties that are hard hit by disasters (at least $10 billion in damages), white people gained nearly $126,000 in wealth, while Black, Latinx and Asian people lost wealth. In other words, both disasters and disaster recovery efforts worsen racial economic inequality. This trend also occurs in relation to homeowners, accounting for a $133,000 increase in inequality between homeowners and renters.

Louisiana’s Road Home Program, established with federal funds to address the housing needs of displaced residents after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, was riddled with problems. In one of many lawsuits filed about the administration of the Road Home Program, the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center, the National Fair Housing Alliance and individual homeowners representing others who suffered discrimination alleged discrimination under the Fair Housing Act related to the procedure for calculating homeowners’ grants for repairs. The formula allowed either the pre-storm value or the cost of repairs, whichever was lower. A federal judge ruled that the use of the pre-storm value disparately harmed Black homeowners, as their awards were more likely to be lower than the cost of repairs, even though the damages and cost of repairs were the same.

Marcia L. Fudge, then-secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), recognized the years of problems with the Road Home Program when she announced its closure in February 2023. “For more than 17 years, many Louisianans have not had the freedom to fully move on from the pain and trauma of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita — that changes today,” said Fudge.

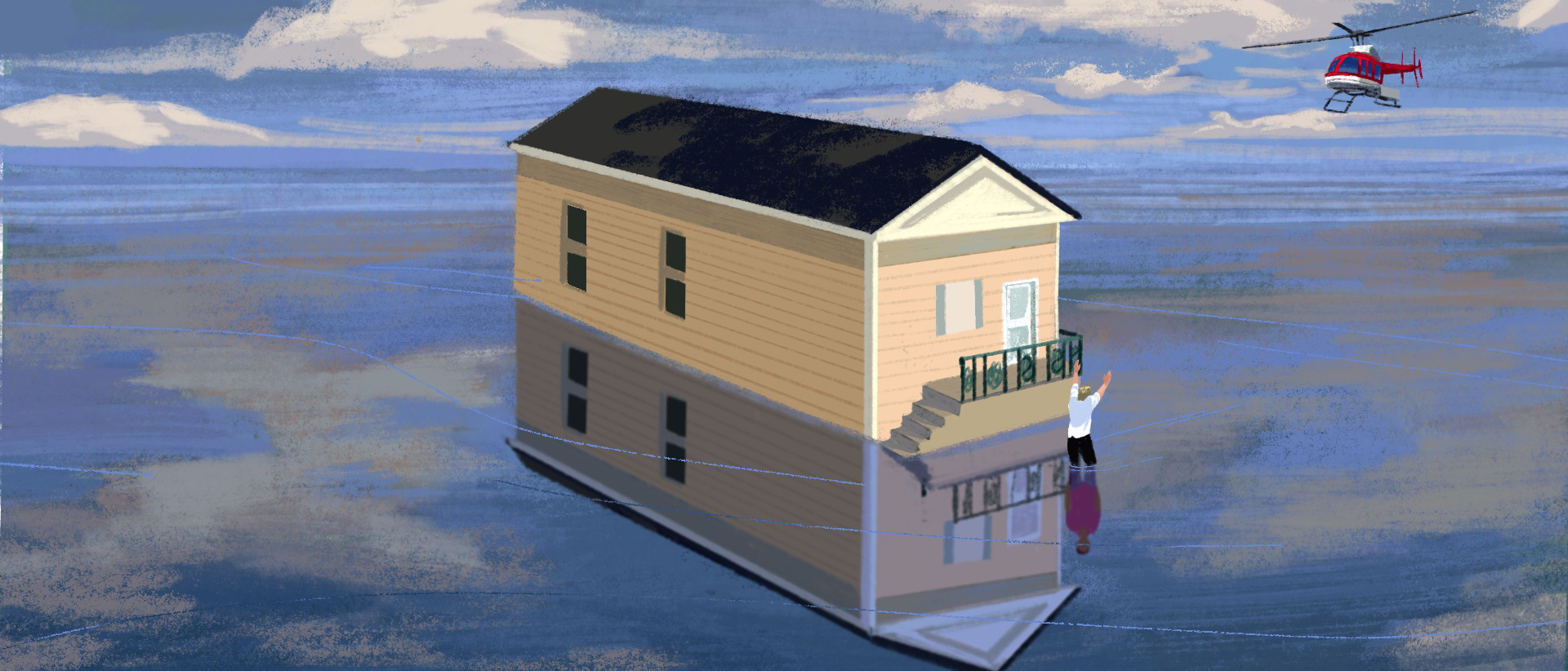

The worsening of racial economic inequality after disasters is not limited to Louisiana. Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Flood Mitigation Assistance program funds — used to elevate houses in flood-prone zones — have gone overwhelmingly to white or wealthy communities. Often, the disaster assistance has been used to elevate waterfront homes, allowing reduced insurance premiums and profits on the resale of the newly elevated homes.

In 2022, Politico reported that half of the money FEMA used to elevate homes in Florida went to communities whose population is more than 90% white or whose median household income is more than $100,000. Although flood damage has occurred virtually everywhere along the Florida coast, half of FEMA’s elevation money has gone to just seven small, predominantly white and wealthy towns on the Atlantic or Gulf coasts. Florida is one of 12 states where more than 50% of flood elevation grants went to wealthy or white communities. In four states, more than 75% of the money went to wealthy or white communities.

There are many policy decisions underpinning this discriminatory result, some of which are simply attributable to program design that is reproducing inequity. Programs can be designed differently, and different policy choices can be made to address community-wide projects to reduce flooding, particularly in areas with social vulnerability to disasters such as poverty. But rebuilding after disasters often becomes synonymous with displacement and gentrification, disproportionately harming and permanently displacing Black and Brown communities and low-income populations.

Homelessness is a humanitarian crisis, not a crime.”

— Anjana Joshi, SPLC senior staff attorney

As a result of Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma combined, more than 1 million homes were damaged. The areas damaged by Hurricane Katrina generally had higher percentages of Black residents, higher percentages of renter households, and higher poverty rates compared to undamaged areas.

The destruction of housing posed long-term challenges in New Orleans and amplified the challenges of an equitable recovery. By 2010, the availability of public housing had plummeted from pre-Katrina levels due to a combination of policy decisions. At the same time, the housing cost burden (the number of people spending more than 30% of their income on housing) had skyrocketed. Before Hurricane Katrina, a majority of renters in New Orleans were not cost-burdened. Eight years after Hurricane Katrina, more than 58% of renters were cost-burdened, including 37% who spent more than 50% of their income on rent.

The inequity of disaster recovery reproduces itself over and over again. New Orleans, predictably, faced a crisis of homelessness after the destruction of so many homes. More than two years after the storm, there were more than 11,600 homeless people in the city. Through a variety of efforts, the city and social service providers worked to reduce those numbers significantly — a reduction of 90% — by 2019.

By then, a different type of disaster was about to strike, this time a global pandemic that brought its own combination of economic and housing dislocations and continued worsening of racial economic inequality after the expiration of COVID-era relief. Homelessness in New Orleans soared by 20% between 2022 and 2024. The proportion of Black people experiencing homelessness was rising, at the same time the proportion of white people experiencing homelessness was decreasing in New Orleans.

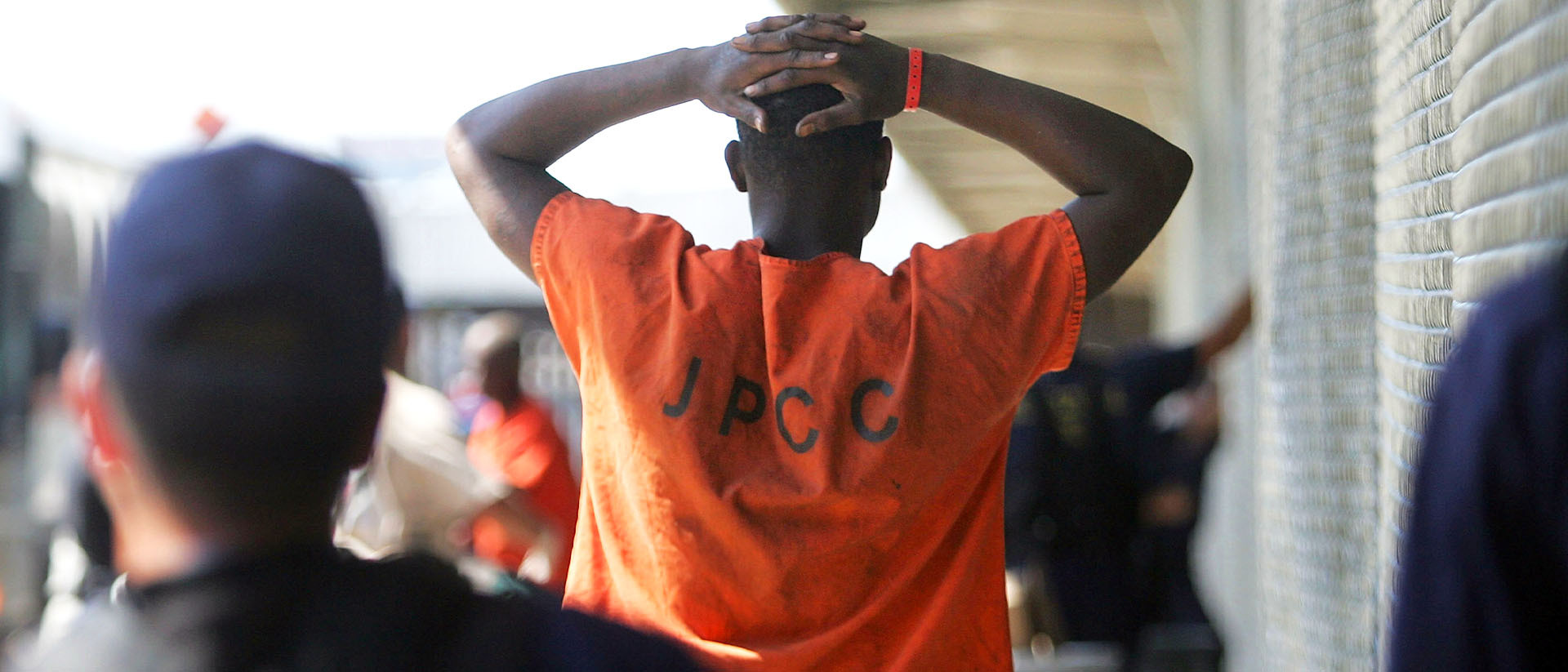

The issues of housing and homelessness in New Orleans exploded into the national news again in recent years when the state of Louisiana embarked on a campaign of sweeps — the forced eviction, displacement and seizure of property and liberty of persons experiencing homelessness — from areas surrounding the Superdome in advance of high-profile events including Taylor Swift concerts in 2024, and the Super Bowl in early 2025.

The SPLC and MacArthur Justice Center worked to stop the seizure and destruction of property, evictions and displacements, winning a series of court orders in December 2024. After a preliminary injunction, the lawsuit was dissolved by the Louisiana Supreme Court on procedural grounds, the parties reached a settlement, and the plaintiffs voluntarily dismissed the case. The state of Louisiana’s actions took place across a broader national trend of localities using increased punitive measures to address issues of homelessness rather than tackling the root causes of the housing affordability crisis that is causing so many people to sleep on the streets of the richest country in the world.

As SPLC senior staff attorney Anjana Joshi said in a statement released during the case, “Homelessness is a humanitarian crisis, not a crime. New Orleans playing host to several high-profile events — such as the Taylor Swift concerts, the Bayou Classic and the Super Bowl — is no excuse for state agencies to further harm New Orleans residents who are unhoused. We urge the State to stop interfering with the city’s ongoing efforts to transition people into housing and provide other critical services.”

Make no mistake, the impact of natural disasters does in fact discriminate. But our responses should not.

How to effect change?

- Reduce the number of administrative burdens that property owners, homeowners and renters must face to receive disaster recovery assistance.

- Increase the amount of natural disaster aid for rebuilding and consider individual need, in addition to pre-disaster property value, in calculating grant award amounts.

- Address housing affordability and the root causes of homelessness instead of criminalizing people experiencing homelessness.

- Strengthen food security and social safety net programs, as well as investment in programs designed to break the cycle of poverty and economic instability.

Kirsten Anderson is the SPLC’s deputy legal director for economic justice.

Illustration by Tara Anand.