The Politics of Civil War Memory

At no point during the Civil War did any Confederate symbol come within six miles of the U.S. Capitol. Yet on Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol rioter Kevin Seefried carried a Confederate battle flag right inside. What we think of today as the Confederate flag was one of many flags of the Confederacy. Segregationists resurrected it in the 1950s and ’60s as a clear symbol of resistance to the ascendant Civil Rights Movement. Today it remains a symbol of white supremacy and antigovernment ideology and has also been used by President Donald Trump’s supporters.

Lost Cause mythology has been central to Trump’s movement. He romanticizes the gender and racial hierarchies of the past, valorizes Confederate leaders and symbols, and demonizes those who would remove Confederate memorials as “angry mobs” trying to “wipe out our history.” The Confederate anthem “Dixie” was played at Trump’s Madison Square Garden rally on Oct. 27, 2024, an event filled with racist harangues and ridicule. For context, the University of Mississippi banned the song from games and school events in 2016. On several occasions, Trump has identified Confederate memorials with his movement’s values. In summer 2020, he proclaimed that “our nation is witnessing a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values, and indoctrinate our children.”[1]

“Angry mobs are trying to tear down statues of our founders, deface our most sacred memorials,” he said, identifying Confederate insurrectionists as “our founders.” Far-right pundit Tucker Carlson has similarly tried to forge a deep connection between Confederates and his audience. Carlson attacked Americans who advocate removal of Confederate memorials in a speech at a Trump rally on Oct. 23, 2024. “They tore down statues to [Confederate] memory,” Carlson said. “They went out of their way to humiliate you and spit on you and the graves of your ancestors.” Carlson hoped his audience would identify so strongly with the Lost Cause myth that they would feel its rejection as their humiliation. He encouraged the crowd to view Confederates as their ancestors, regardless of whether they had ancestors who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. The Lost Cause, he insisted, is their heritage. Its rejection is their rejection.

In November 2020, Trump formed what he called the 1776 Commission to develop a history curriculum in opposition to the “deliberately destructive scholarship” that he claimed Americans encountered in school. The 1776 Commission report called this scholarship the “intellectual force behind so much of the violence in our cities,” including the “defamation of our treasured national statues,” i.e., Confederate memorials. The American Historical Association (AHA) charged that the authors of the report consulted no professional historian, did not engage with recent historical scholarship, and “reject[ed] recent efforts to understand the multiple ways the institution of slavery shaped our nation’s history.”

“The authors call for a form of government indoctrination of American students,” the AHA concluded. In July 2023, the Florida State Board of Education, appointed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, announced a new state history curriculum that follows Lost Cause mythology. The curriculum requires teachers to tell students that “slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.” Educators and students reacted in horror. Florida Education Association President Andrew Spar wrote: “DeSantis is pursuing a political agenda guaranteed to set good people against one another, and in the process, he’s cheating our kids. They deserve the full truth of American history, the good and the bad.”

In response to the Florida curriculum, which also deletes all references to white supremacy, leaves only a single mention of lynching, and refers to enslaved Americans as “Africans,” even after their families had been in America for generations, AHA executive director James Grossman asserted in a response published on the AHA website: “The remedy for discomfort is not to ignore or marginalize the lasting effects of legal, economic, social and cultural institutions that condoned buying and selling other human beings for nearly 250 years. Our work as historians is chock-full of stories that can inspire students and readers without obscuring essential concepts.”

Moms for Liberty, an antigovernment extremist group founded in 2021, has supported legislation in 18 states that bans teaching anything that could be described as “critical race theory” (CRT), a decades-old academic concept that the hard right often uses to mean any subject matter that makes the uncomfortable, such as race and Black history. In Tennessee in 2021, Moms for Liberty members used the state’s anti-CRT law to challenge a book by civil rights hero Ruby Bridges about her experiences as the first Black child to attend the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana. Only 6 years old when courts ordered her school district integrated in late 1960, Bridges and her family suffered greatly. As the Equal Justice Initiative writes: “Despite threats and retaliation against her family, including her grandparents’ eviction from the Mississippi farm where they worked as sharecroppers, Ruby remained at Frantz Elementary. The next year, Ruby advanced to the second grade, and the school’s incoming first grade class had eight Black students.” In place of Bridges’ book, Moms for Liberty has recommended The Making of America, a 1985 textbook that claims enslaved people did not want or need freedom.

The hard right clearly understands that having a story about American history is essential to winning “a war of ideas” in American politics, as Edward Pollard observed two centuries ago. Just as the UDC sought to influence school curricula to establish Lost Cause myth as historical fact, the contemporary hard right has made influencing school curricula a top priority. “As long as we have a politics of race in America,” wrote U.S. historian David Blight, “we will have a politics of Civil War memory.”[2] Indeed, Donald Trump’s racial politics are tied up with Civil War memory.

The day after the 2024 presidential election, racist groups once again used the brutal legacy of slavery to terrorize and intimidate Black people. In several states across the country, Black Americans received text messages with references to slavery. The messages targeted students, including middle school and high school kids. “Report to the plantation,” demanded some messages. “You have been selected to pick cotton.” Texts often mentioned recipients by name and warned them of “slave catchers” who would take them to “the plantation.” Some of these texts referenced Trump’s reelection, and some used the N-word. All used the memory of slavery to terrorize and intimidate Black Americans in the aftermath of the election.

Telling stories about the past is one of the ways humans understand who they are and imagine their future — individually, as a society and as a nation. The Lost Cause is a fictional account of the past, created for the purpose of maintaining white supremacy — and it is vital that Americans recognize the Lost Cause for the racist distortion it is when it shows up in contemporary political narratives. But exposing the lies and cruelty of Lost Cause mythology is not enough. Telling true stories about the South’s real heroes is essential for inspiration and wisdom in the present movement for justice and democracy.

Victories Won and Challenges Overcome

Since 2022, the year of the third edition of this report, progress in the number of Confederate memorials removed or renamed has slowed, but it has not stopped. While the movement has achieved significant victories in the past two years, some setbacks also illustrate the challenges of continuing this work — challenges that some grassroots activists and communities are nevertheless overcoming. The work continues. And the past two years saw important victories worth celebrating.

In 2023, the U.S. military completed the task of renaming all nine military bases named after Confederates. The fact that the United States had military bases named after men who committed treason and waged war against this nation demonstrates the tremendous success of the Lost Cause in its total rewriting of Civil War history and the image of Confederate leaders. In December 2020 Congress passed legislation — with a bipartisan, veto-proof majority —requiring the Department of Defense to remove the names of all bases named after Confederates. This bipartisan legislation also created a nonpartisan Naming Commission, chaired by retired Navy Adm. Michelle Howard, tasked with finding appropriate names honoring Americans and American values in place of Confederates. The SPLC supported the work of the Naming Commission and made the case for removing Confederate names. In a blow to this bipartisan congressional achievement, Trump’s secretary of defense, Pete Hegseth, has, at the time of writing, changed the names of two bases back to their former Confederate monikers, and has signaled his desire to continue this effort with other bases. In February 2025, as one of his first acts, Hegseth changed Fort Liberty back to Fort Bragg. Because bipartisan legislation prevents Hegseth from choosing a Confederate name, the secretary renamed Fort Liberty after Pfc. Roland Bragg, who earned the Silver Star and Purple Heart during the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, rather than Confederate General Braxton Bragg. Tweeting “Bragg is back!” Hegseth recalled the Confederate name, even as the law forced him to choose a different Bragg to honor Sen. Jack Reed of Rhode Island, ranking member of the Armed Services Committee, called Hegseth’s move “cynical.” “Secretary Hegseth has not violated the letter of the law, but he has violated its spirit,” Reed stated, adding that Hegseth “has insulted the Gold Star families who proudly supported Fort Liberty’s name, and he has dishonored himself by associating Private Bragg’s good name with a Confederate traitor.” In March 2025, Hegseth changed the name of Fort Moore back to Fort Benning. Fort Benning was named after Henry L. Benning, a particularly radical secessionist and white supremacist. In his place the nonpartisan Naming Commission chose to honor Hal Moore, a Korean War and Vietnam War veteran who earned the Distinguished Service Cross for valor, and his wife Julie, an advocate and leader in supporting military families. Like he did with Bragg, Hegseth chose another Benning to honor, WWI veteran Army Cpl. Fred G. Benning.

Renamed U.S. Military Bases

*— Secretary of defense Pete Hegseth signed memorandums to change Fort Liberty to Fort Bragg in February 2025 and Fort Moore to Fort Benning in March 2025

In December 2023, Arlington National Cemetery removed its Confederate memorial, overcoming a lawsuit that attempted to block removal. The Confederate Memorial at Arlington, commissioned by the UDC, represented a uniquely offensive piece of Lost Cause propaganda. The U.S. government used the cemetery, once a settlement for people freed from slavery during the Civil War, as a burial ground for Union dead. A Confederate memorial there, of all places, where in 1871 Frederick Douglass bemoaned the amnesia that allowed Americans to celebrate both sides of the war equally, represents a particular insult to the memory of those who died for the Union and emancipation. Imagine the pain of Black Americans, in particular, who have ancestors buried in Arlington as they attempt to honor their dead under the shadow of those who fought for their enslavement.

The memorial contained a depiction of a Black “mammy” weeping and taking a child from a Confederate soldier into her arms so that the soldier could go fight to preserve slavery. The meaning of this racist caricature was not lost on contemporary observers. In 1914, the year the memorial went up, U.S. Secretary of the Navy Hilary Herbert wrote that the purpose of the memorial was to correct “false ideas” in the popular 1800s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and to memorialize slavery as part of a simpler, happier time. “The kindly relations that existed all over the South between the master and the slave,” Herbert wrote, is “a story that can not be too often repeated to generations in which Uncle Tom’s Cabin survives and is still manufacturing false ideas.” What Herbert labeled “false ideas” were simple, obvious truths that slavery was brutal and inhumane, defined by constant cruelty, degradation and violence, and that enslaved people longed for and fought for freedom. Herbert praised the UDC for erasing this reality with the Confederate memorial, writing that “one leading purpose of the U.D.C. is to correct history.”

The memorial finally came down in December 2023. Six months later, on June 13, 2024, U.S. Rep. Andrew Clyde (R-Ga.) introduced an amendment bill to reinstate it. Clyde’s amendment, H.Amdt. 978, was defeated with bipartisan opposition, 192-230.

While the Arlington memorial received the most national attention, the movement against the Lost Cause has achieved other notable victories in the past two years. In December 2023, after a sustained campaign by grassroots groups and community members, Mayor Donna Deegan of Jacksonville, Florida, ordered the removal of a Confederate memorial from Springfield Park, on the edge of a historically Black neighborhood, where it stood since 1915.

The movement against the Lost Cause also achieved a rare victory in Mississippi. In September 2024, Mayor Charles Latham of Grenada, Mississippi, removed the Confederate memorial in the city’s courthouse square. Grenada’s city council had voted to remove the memorial in 2020, but the council had failed to take further action until Latham took up the issue. The memorial, featuring Confederate President Jefferson Davis and a dedication claiming Confederates fought for “truth and right,” was erected by the UDC in 1910.

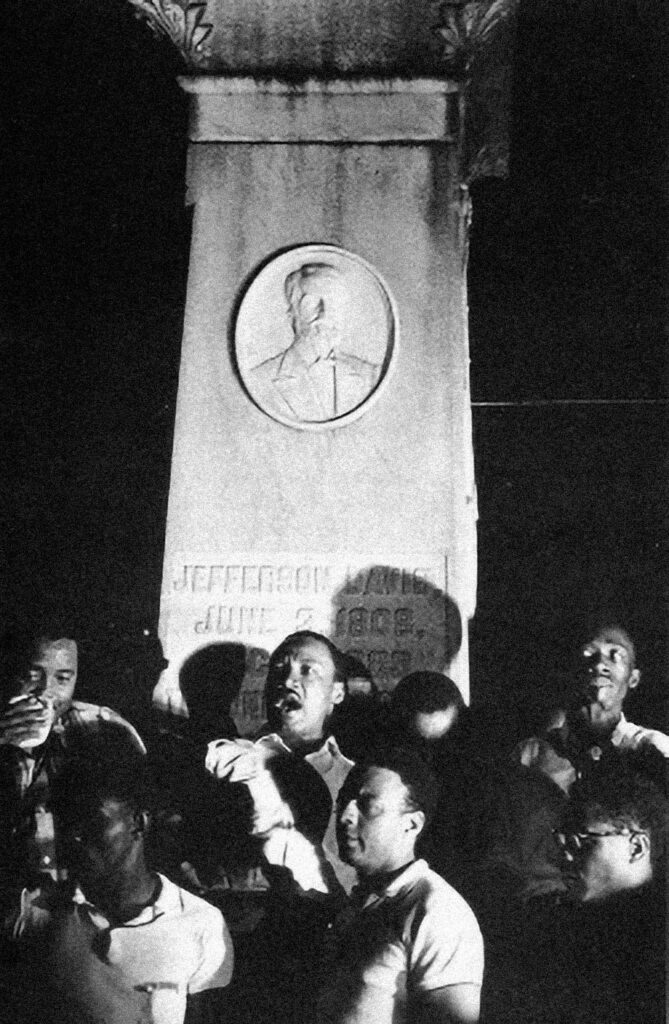

When civil rights activists held a rally in Grenada in 1966, an activist climbed the monument and defiantly wedged an American flag above Davis. A mob of Klansmen and other white supremacists poured into Grenada to defend the memorial and oppose the activists’ demands for voting rights, even attacking children when Black students and activists sought to integrate local schools 12 years after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board. This story should serve as a reminder that the movement against Confederate memorials and the Lost Cause myth is part of a long history. The Grenada memorial has been removed to an obscure location where it is not in plain sight, but the city may face a lawsuit from a Republican state representative for relocating it. Similar lawsuits in the past — like the one that failed to block the removal of Arlington’s memorial — have not been successful.

At least two of the movement victories in the past two years were defensive. In both 2023 and 2024, the Florida State Legislature considered bills (HB 1607/SB 1096 and HB 395/SB 1122) aimed at making removal of Confederate memorials much more difficult. The legislation would give Gov. DeSantis the authority to fine any government official involved in taking down a Confederate symbol in the state. Since 2017, Floridians have successfully removed 31 Confederate symbols and removed Confederate names from six public schools. If the bills had been successful, students in Jacksonville attending Riverside High School, whose student population is 70% Black, would once again be attending Lee High School. Thanks in part to grassroots groups who held rallies, collected signatures and lobbied elected officials, the bills have never passed. Given Trump’s and Hegseth’s support for restoring old Confederate names of military bases, more of the movement’s victories may have to be defensive in the coming years.

Some communities, however, continue to play offense. In Montgomery, Alabama, a 17-year-old student named Jeremiah Treece introduced a petition to remove Confederate flag imagery from Montgomery’s official city flag, adopted in 1952. Treece called his petition “Change the Flag. Grow from History,” connecting how Americans remember the past with the collective action and power they can wield together in the present. Treece’s understanding of the use of history in shaping ideas about the present is significant, especially considering attacks on teaching the truth about slavery and the Civil War coordinated by hard-right organizations and their allies in government. Treece said his experience starting the petition and facing opposition “has definitely made me realize how much history has divided the country — not just the city, but the country — and how much we still have to overcome.”

“Every day in this city, we are walking on land that was old plantations, on streets that were built by my ancestors. That history is part of this city,” Treece said. “Of course, there’s a lot of amazing things that have come from this city as well, like the Civil Rights Movement.” Treece’s petition currently has over 2,500 signatures.

In spring 2024, in Tyrrell County, North Carolina, a group of Black community members filed a federal lawsuit seeking the removal of a Confederate memorial in front of the county courthouse with the inscription: “In appreciation of our faithful slaves.” The Tyrrell County citizens’ lawsuit argues that the memorial in front of the courthouse violates the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. Citizens have long been fighting to remove that racist memorial, organizing demonstrations and speaking at Board of Commissioners meetings. This is the first time they have tried using the courts.

Taken together, the victories of the last two years, as well as the new efforts of Jeremiah Treece’s petition in Alabama and Tyrrell County’s lawsuit in North Carolina, illustrate a wide spectrum of tactics that the movement against Confederate memorials can pursue. Action has come from the federal government, from mayors, from city councils, from community groups pressuring legislators, from a student petition, and from a federal lawsuit. The groundswell of demonstrations in 2020 continues to inspire action years later.

Setbacks

In 2024, the movement against Confederate memorials suffered two significant setbacks. One occurred in Florence, Alabama, where community groups have been working since 2020 to remove a Confederate memorial in front of the county courthouse. Having no success at removal, activists changed tactics and advocated adding an historical marker that contextualizes the memorial. The Florence City Council rejected the measure in May 2024. “The community was livid,” said Camille Bennett, executive director of Project Say Something, a grassroots organization that has led the effort. Bennett explained that the City Council’s vote only motivated more people to oppose the monument. “They want to be involved,” she said, adding: “I’m hopeful. You can’t be an activist and not be hopeful. I don’t know where this road is going to take us, but I know that our fight around the monument has been a vehicle for exposing the racism that we live with within this community. And that has only made us stronger.”

Another setback came in May 2024. Four years after the school board in Shenandoah County, Virginia, voted to remove Confederate names from two public schools, board members elected in 2021 voted to restore them. Mountain View High School and Honey Run Elementary School will once again be called Stonewall Jackson High School and Ashby-Lee Elementary School, honoring Confederate generals Stonewall Jackson, Turner Ashby and Robert E. Lee. “I really just don’t like the idea of walking into a building named after someone who did want me, and people like me, to be enslaved,” said A.D. Carter, a Black student at Mountain View. “It just makes me feel like I don’t necessarily belong there.” A local teacher resigned over the restoration of the names, and some families are considering leaving as well. “This might not be the community for us any longer,” said one parent.

The setbacks in Alabama and Virginia reflect the uphill battles that opponents of the Lost Cause have always faced, rather than any new trend. In a 2022 poll conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), 52% of Americans supported maintaining Confederate memorials, while 44% favored removal. The poll found majority support for removal only among Black respondents, with 64% in favor and another 23% in favor of adding historical context. When PRRI repeated this survey two years later in 2024, results were similar to the 2022 survey, showing that educational work must continue and improve. The good news is that when people are informed about the true history of Confederacy and the Civil War, they become more likely to support removal, according to a 2021 survey of Georgia voters. But as far-right extremist groups take control of school curricula that peddle racist Lost Cause propaganda, educators and communities will have to look for creative new ways to teach and to tell the true history of the Civil War and slavery.

Illustration by Simón Prades

[1] “Donald Trump orders creation of ‘national heroes’ garden,” BBC, July 5, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53292585; Libby Cathey, “Trump’s history of defending Confederate ‘heritage’ despite political risk,” ABC News, June 11, 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trumps-history-defending-confederate-heritage-political-risk-analysis/story?id=71199968; Annie Carnie, “Trump Uses Mount Rushmore Speech to Deliver Divisive Culture War Message,” The New York Times, July 3, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/03/us/politics/trump-coronavirus-mount-rushmore.html; Weijia Jiang, “Trump: American History Is Being ‘Ripped Apart’ With Removal Of Confederate Statues,” CBS Miami, August 17, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLnaXGl0Vz4.

[2] David Blight, Race and Reunion, pg. 4.

For a complete list of citations used in this report, click here.