Editor’s note: This is the fourth and final story in the “Gullah-Geechee vs. Greed” series about the fight to preserve the last of the Black communities on these islands off the southeast Atlantic coast.

In the video: Amid a shrinking population, unending legal battles and decaying or nonexistent infrastructure, Gullah-Geechee culture and the people who represent it have survived and are forging forward. Gullah-Geechee descendants Parthenia Myers, Yolawnda Cohen-McKinney and Taiwan Scott share their stories and visions for the future. (Credit: Yolawnda Cohen-McKinney, Da Gullah Geechee Pavilion. The Gullah Geechee Museum of Hilton Head. John Margolies Roadside America. Toptropicals.com)

When you get out of Hogg Hummock on Sapelo Island, all signs of infrastructure disappear. If you want to access the northern part of the island, the odds of finding an open vehicular path are a crapshoot at best.

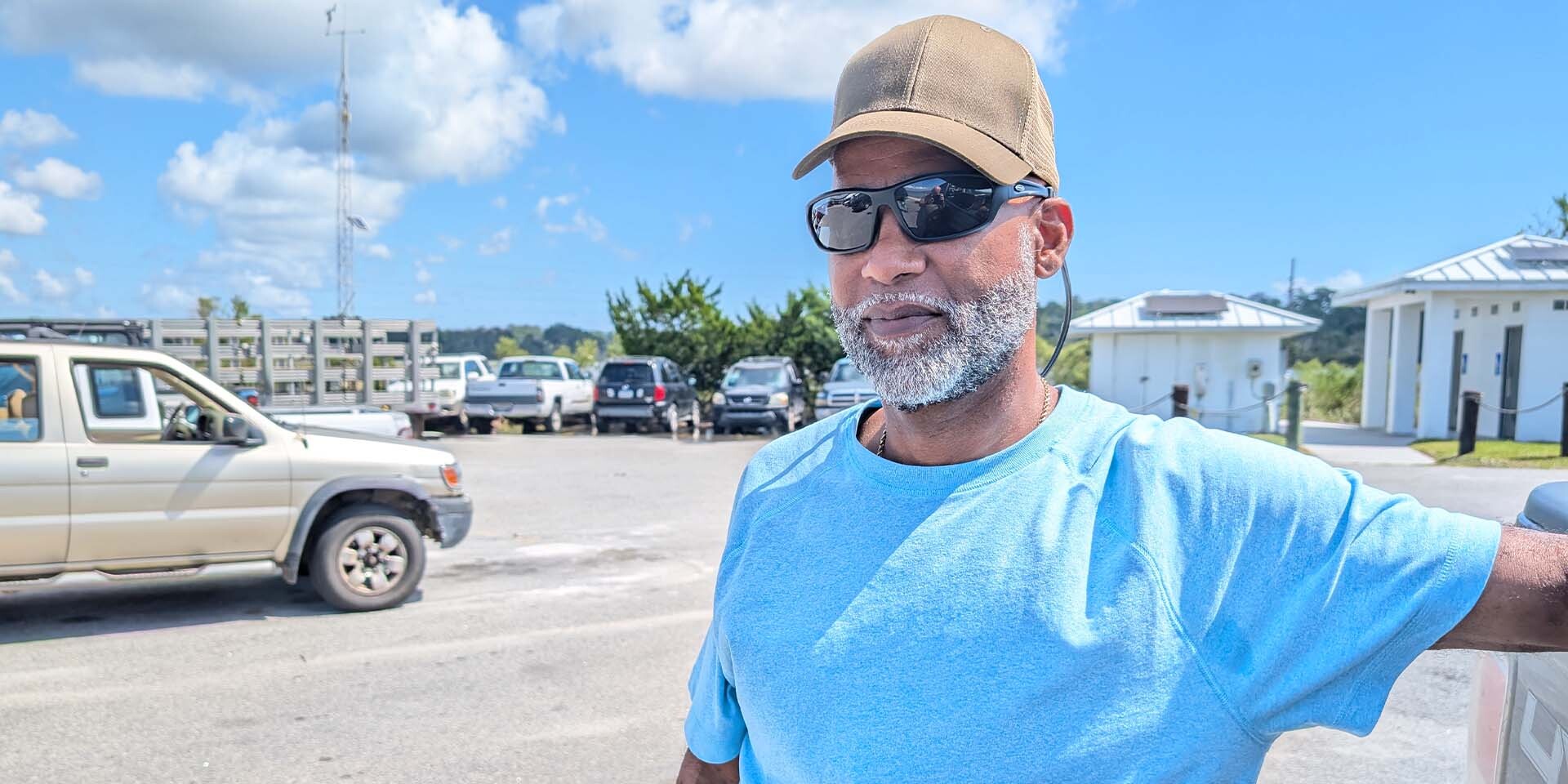

“That’s gotten to be too treacherous to even try,” said J.R. Grovner, a lifelong resident of Sapelo and McIntosh County. He surveyed the deep ruts and standing water in a narrow dirt lane. “I used to take that road.”

Grovner’s mother, Yvonne, and father, Ire Gene, are plaintiffs in a lawsuit they and several other Geechee residents have filed against a zoning ordinance that has allowed the construction of larger properties on the island.

That ordinance, passed in 2023, allows homes more than double the modest 1,400- square-foot limit that has been in place since 1995. It allows 3,000-square-foot homes that would fuel a rise in tax assessments on property, forcing out the few dozen Gullah-Geechee people in one of the last historic Gullah-Geechee sea island communities in the U.S.

The lawsuit claims that McIntosh County violated the islanders’ due process rights, failing to give them and others a meaningful opportunity to be heard on the changes to the zoning ordinance. It also claims the county is failing to protect the historic and cultural integrity of the Hogg Hummock community.

“Ultimately, this case is about holding local government actors accountable to the people they serve,” said Malissa Williams, a senior staff attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Economic Justice litigation team, which is representing the Gullah-Geechee plaintiffs in the case over the ordinance. “If this lawsuit helps to ensure a fair and equitable process when the county enacts the next zoning ordinance, then I think that would be a meaningful outcome for the Hogg Hummock community.”

Behind that ordinance are forces fighting to deprive the native islanders of their birthright — the property their formerly enslaved ancestors left for them and the generational wealth it represents, which could amount to billions of dollars, and the power to shape the future of their ancestral land.

The great-great-grandfathers of current Geechee residents purchased 1,134 acres of land in the period from 1870 to 1890. The deeds from those sales, still on record, are now clouded by a century-old swirl of tax records, poorly documented inheritances and misleading McIntosh County Tax Assessor records. These errors and omissions paved the way for the problems current residents and heirs have seen in trying to sell or develop their property on Sapelo.

The real-world effect could be seen as Grovner turned down another road. Instead of lush woodland, he passed through a blackened clearing that recalled an old Apollo moon mission photograph of the dark, barren lunar surface.

“The Georgia Department of Natural Resources [DNR] in the last three years has cleared all of this,” Grovner said as he passed the area. “It was stands of mature pine. And they’re burning it off. They’re treating it as their own, even though DNR is fully aware that there are Gullah-Geechee private interests in all of this land.”

And that, Grovner says, is the reason the roads are often either unserviceable or inaccessible.

“All of this,” he said, gesturing to the encroaching woods. “They’re treating as if it is a settled argument and they are the owner. So that is their approach. If we can keep it out of sight, out of mind, impossibly hard to access, then maybe they’ll forget about it.”

According to a directive issued in August, DNR now forbids Gullah-Geechee people and others to travel across DNR-held land to access their land in Raccoon Bluff during the hunting season, which effectively runs all year long because of the prevalence of invasive wild hogs.

And, as with any fight over property, there’s money to be made. While other sea islands have already been developed into luxury destinations such as Hilton Head off the South Carolina coast, Sapelo has remained largely intact, a wilderness that has some developers champing at the bit.

Almost, but not entirely, different

While there may be a natural impulse to compare the commercialization of Hilton Head to the lush vegetation on Sapelo Island, it would be unfair to the communities of each.

“The development of Hilton Head Island is far more advanced than on Sapelo Island,” said Anjana Joshi, a senior staff attorney with the SPLC’s Economic Justice litigation team. “But each of the Gullah-Geechee communities on these two islands has its own vision for economic sustainment and self-determination rooted in those realities. A comparison of the two places without this nuance risks ignoring the decades of resistance and organizing that each community has engaged in, and continues to engage in, to preserve their land and legacies.”

In fact, the issue of heirs’ property — land passed down from generation to generation without proper title or deed — is common in both communities.

“Why have we been losing so much Gullah land?” said Taiwan Scott, a Gullah native of Hilton Head Island. The Gullah-speaking descendants on Hilton Head now make up less than 6% of the population, holding fewer than 1,000 acres of land.

“This heirs’ property issue, it’s all calculated,” Scott said. “The rules and regulations that have been stopping us from being able to utilize our property and then developers, or the town themselves, are the ones who end up with our property.”

On Sapelo, Grovner and Reginald Hall have made a crusade out of their search for answers to the provenance and title of property either taken or stolen from the Geechee- speaking people of the island.

Hall and others, such as members of One Hundred Miles, an environmental and cultural justice organization, have put together a comprehensive sketch of the people who they think are behind the moves to open the island up to gentrification. That sketch is the result of multiple record requests for emails between DNR and potential developers. It’s also the result of allied residents’ visits to the University of Georgia archives and other research trips.

The list of those building new homes on the island is a long one and represents some of the most powerful people in the state, if not the nation. A grandnephew of the late Richard B. Russell, the former U.S. senator and Georgia governor for whom the Russell Senate Office Building in Washington, D.C., is named, has owned numerous properties. An Auburn University football coordinator recently became a vacation property owner. Descendants of the Spalding family, which once enslaved people on the island, have built a home there. Other full- and part-time residents claim lineage to politicians, judges and industry-leading companies.

Just this week one of those new residents, William Hodges, the son of a former Georgia Superior Court judge, circulated an email to the island’s primarily white, new property owners announcing that the “Hog Hammock Community Church” would hold its first services at the former Sapelo Community Center on Oct. 26. The county-owned community center, which was once used for receptions, meetings and other neighborhood events, was leased to another new resident, former Glynn County Commissioner Tony Thaw, for private commercial use as a bar and grill after McIntosh County used American Rescue Plan Act funds to renovate the structure.

Billions at stake

As with any good story, to get to its heart one must follow the money, which is what Hall and Grovner have been doing.

“For the first time in the history of our folk, since the Reynolds Foundation, R.J. Reynolds and then the state absconded with it [Geechee property], we now have a state court case requesting $2 billion for that land on the north end,” Hall said, speaking of the 1,000-acre tract in the Raccoon Bluff area. “The last sale was $2 million for one acre. Take 1,000 acres multiplied by $2 million each and we’re at $2 billion.”

Hall’s figures, however, do not stop there. Building an estimated 250 homes on half-acre lots could bring in up to $15 billion.

Hall also noted how R.J. Reynolds Jr. forced residents out of several Geechee communities around the island, including Raccoon Bluff, in the 1950s and 1960s. It was part of an effort to create a hunting reserve. Reynolds died in 1964. Hall said the property was designated a wilderness reserve after Reynolds’ widow sold it to the state — an action that was as much an effort to keep it out of Gullah-Geechee hands as it was for providing a preserve for sportsmen and nature lovers.

There were at one point 12 Gullah communities on Sapelo Island, with a half-dozen left after World War II. By the time Racoon Bluff was razed in the 1960s, only Hogg Hummock was left.

“They turned it into a state wildlife preserve. Makes it a hundred times harder for us to go and get that land back — not that we can’t,” Hall said. “Because we want to own all the clear titles. Because they took six communities of ours and wiped them out.”

‘Don’t become extinct’

While these questions are making their way through the courts, the residents in the remaining Gullah-Geechee communities are looking to capture and keep what they can of the life they have come to know.

“I think we need support — of the town, of the state,” said Yolawnda Cohen-McKinney, a sixth-generation Hilton Head native islander. “We have the Gullah-Geechee Corridor that [U.S. Rep.] James Clyburn established to educate and ensure that the [culture and communities] remain and don’t become extinct. There are plans to help but there’s more that can be done that’s not being done.”

Yvonne Grovner, another plaintiff in the SPLC’s lawsuit and a longtime Sapelo resident, said she wants the character of the island to remain as she has known it over the last 45 years.

“The most change on the island is that we’ve got less people now in the community,” Yvonne Grovner said. “The numbers have gone down, and these big houses being built in Hogg Hummock look out of place.”

She said the community aspect of the island has been degraded over time due to the isolation enforced through limitations on ferry access.

“When I first moved to the island, it was much more than just the older people who used to live there and have passed away,” she said. “I used to like to go visit and talk with a lot of the old people. Like Miss Maddie Carter, she’s the one who taught me how to do sweet potato poon and some of the old-time cooking and stuff like that.”

The culture and the beauty of the environment are not only for the Gullah-Geechee community, she said.

“You can’t find places like Sapelo no more, which would be an important reason to keep it,” she said. “Yeah, to keep it the way it is. Pristine. Say you go to a beach. When you go to a beach here, you’re the only person on the beach. Where can you go to find that? Nowhere else.”

Image at top: An algae-covered pond near the University of Georgia Marine Institute on Sapelo Island. The Southern Poverty Law Center is representing several of the island’s Geechee residents in a lawsuit disputing a zoning ordinance that has allowed the construction of larger properties there. (Credit: Myisa Plancq-Graham)