Content warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of violence. Reader discretion is advised.

Civil rights activist Flonzie Brown Wright was 12 years old in the summer of 1955 and living in Madison County, Mississippi, when her two cousins, ages 15 and 17, came down from Chicago to visit their grandmother in the neighboring, more rural Leake County.

In those days, Black parents who were part of the Great Migration out of the Deep South sent their children back “home” in summer months to be with their relatives and learn their families’ ways before coming back up north.

But that summer, Brown Wright’s cousins came back home in caskets.

The two teens were walking along a road to the country store when white men in a truck asked them where they were going.

“Well, hop in, we’ll take you,” one man told them.

“They took them into the woods, beat them, chained them to their truck and drug them until my first cousin, Eddie, the older one, was almost decapitated,” said Brown Wright, 83, who joined the Civil Rights Movement after the assassination of Medgar Evers in Jackson in 1963. She also helped Martin Luther King Jr. plan a stop for the 1966 “March Against Fear” in her hometown of Canton after James Meredith, the original, solo organizer of his “Walk Against Fear,” was shot.

“An old lady in a house heard what she thought was dogs moaning and crying, went outside and found the boys lying close to each other,” she said. “My first cousin with a chain around his neck was nearly decapitated. My second cousin lived for two more days and died in the hospital.”

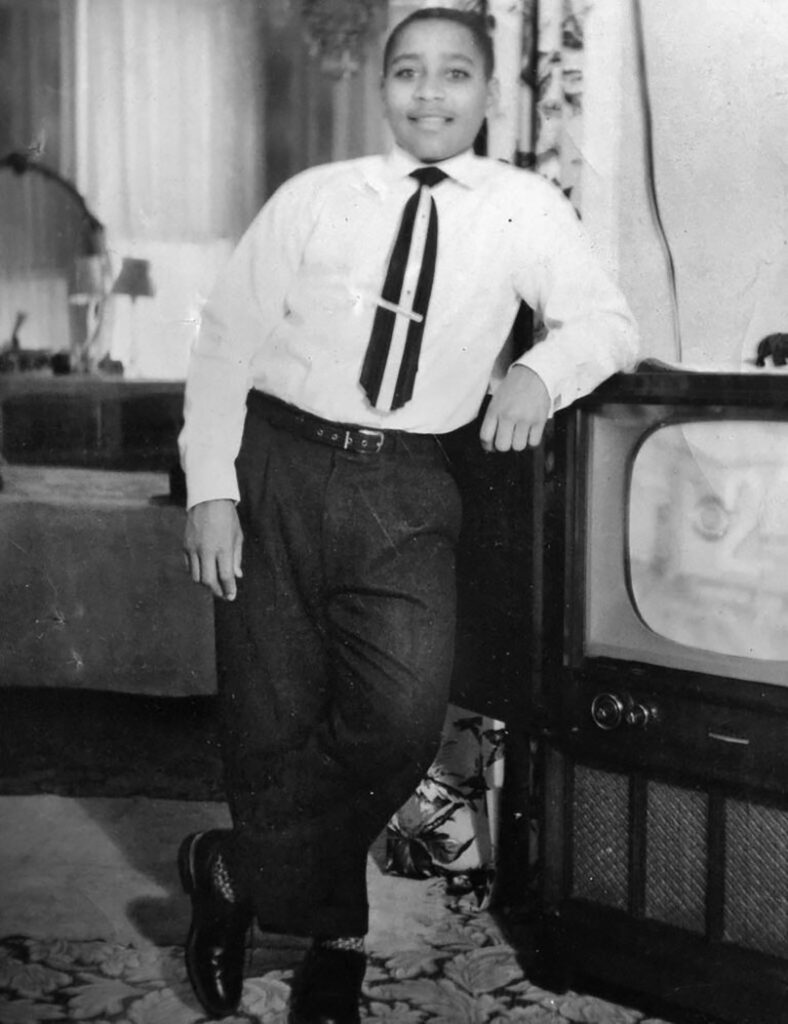

Brown Wright’s cousins were not the only Black teens from Chicago tortured and murdered in Mississippi that summer. But only 14-year-old Emmett Till, who had allegedly whistled at a white storeowner’s wife (she later recanted her testimony that he made sexual advances toward her), was kidnapped, tortured, pistol-whipped, then shot dead in the head.

Then he was thrown, naked, into the Tallahatchie River on this day 70 years ago. A heavy cotton gin fan was tied around his neck with barbed wire to weigh his body down.

As news of his death spread, Till became an international, timeless symbol of crazed, white supremacist, Southern hatred of Black people for the “crime” of not being white.

“The brutal murder of Emmett Till 70 years ago wasn’t an isolated act of violence — it was part of a systematic campaign of terror designed to maintain white supremacy through fear,” said Waikinya Clanton, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Mississippi state office.

“What makes Emmett’s story so powerful is not just the unimaginable cruelty of his death, but his mother’s extraordinary courage in forcing America to confront the reality of racial violence.”

Making people see the horror

Till’s mother, Mamie Till (later Till-Mobley), summoned the superhuman strength to hold an open casket funeral for her son in Chicago. She invited Jet magazine to photograph the gruesome sight so the world could see what blind hatred against a Black human being looks like.

According to one study, 50,000 onlookers filled the streets to view Till’s open casket. Historians agree that those photographs brought worldwide attention to the plight of Black Americans — especially young, Black, male youth — turning the Civil Rights Movement into a powerhouse for social and legislative change.

“Mamie Till’s decision to show the world what hatred had done to her child became a catalyst that helped birth the modern Civil Rights Movement,” Clanton said. “Today, as we continue to fight for justice and equality in Mississippi, we carry forward the legacy of Emmett Till and the countless other victims whose stories remind us that the struggle for human dignity is far from over. Say their names. Michael. Sandra. Breonna. Trayvon. Unfortunately, the list goes on.”

On Aug. 28, a full weekend of events honoring Till’s ultimate sacrifice kicks off at Mississippi Valley State University in Itta Bena, Mississippi. Including a variety of free public programming with registration, presentations hosted by the Emmett Till Interpretive Center will offer tributes to Till and his mother with educational components centering the place his continuing legacy holds in U.S. history.

“John Lewis said that Emmett Till was his George Floyd,” said Daphne Chamberlain, the center’s chief program officer, referencing an opinion piece Lewis wrote in The New York Times shortly before he died.

“As a former academic, every interview I did about the influence of the Civil Rights Movement with pastors, folks who ran for political office, veterans and leaders who continue to do social justice work told me that Emmett Till was the reason they got involved in the movement,” Chamberlain said. “Some of them suffered similar experiences. It was a fearful time for children and no less so for their parents.”

Brown Wright vividly recalls that fear. A few days after her cousins’ murders, she and her two siblings sat quietly in the front parlor of the funeral home where their parents were called to identify the mutilated body of her cousin in the back room.

“I heard my mother scream,” she said. “Even today, 70 years later, I remember hearing the shrill of that scream.”

Like Till’s killers, whom an all-white, all-male jury acquitted after deliberating only 67 minutes, the killers of Brown Wright’s cousins never paid any price for their crime.

They weren’t even identified.

Remembering sacrificial lambs

Several programs will take place this week and over the weekend in Mississippi to commemorate Till’s murder.

On the evening of Aug. 28, there will be a performance of the musical Take Me Back: A Theatrical Journey of Unsettling Memories, about Till and others who were murdered in the fight for civil rights. Click here for a full schedule of events hosted by the Emmett Till Interpretive Center.

The MADDRAMA Performance Troupe of Jackson State University will perform the original work on the Mississippi Valley State University campus in Itta Bena. Mark Henderson, the MADDRAMA founder and playwright, has written a new introduction to the musical honoring Till.

On Aug. 29, also on the Mississippi Valley State campus, the Emmett Till Interpretive Center will host three panels that honor the legacy of Till’s tragedy and his mother’s courage.

Civil rights luminaries such as Joyce Ladner will discuss the “Emmett Till generation,” a term she coined to describe the young Freedom Riders and lunch counter protesters; relatives of Till, Medgar Evers and other activists will discuss their memories of them and their courageous acts. And a panel called “Echoes of the Emmett Till Generation: Voices of Today’s Youth” will explore how today’s youth can be inspired to learn this history and find purpose in it to do meaningful work in their communities.

“We want to show people that these histories are still relevant today,” Chamberlain said. “To explore ways to intentionally engage in and practice racial healing. And we want to create a community that believes in racial equity and inclusion. We want people to be inspired by the stories of civil rights veterans and take actionable steps.”

‘What hatred had done to my son’

Under the Trump administration, the Department of Justice’s Emmett Till Cold Case Investigations and Prosecution Program continues to provide grants in Till’s name for state and local efforts to resolve cold case civil rights-era murders.

The grants were authorized under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act of 2016.

President Trump’s proposed 2026 fiscal year budget zeroed out funding for the three largest hate crime prevention and training grant programs but included $3 million for these grants. In April, however, Attorney General Pam Bondi summarily terminated New Orleans’ Emmett Till grant program.

“These grants have been spectacular successes — among the best restorative justice initiatives ever funded by the Justice Department,” said Michael Lieberman, senior policy counsel on hate and extremism for the SPLC.

Prosecutions of heinous crimes strengthened in 2022 with the passage of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, which for the first time made lynching a federal hate crime punishable by up to 30 years in prison. Under the law, a hate crime that causes “death or serious bodily injury [that] results from a conspiracy to commit a hate crime” will be prosecuted as a lynching.

About 4,500 lynchings occurred in the U.S. between 1882 and 1968, including people under the age of 18, according to the NAACP, although the practice waned by the end of World War II.

“Emmett Till paid the ultimate price,” Brown Wright said. “Mrs. Till had that strength in her. When I sat down next to her during Rev. [Jesse] Jackson’s annual [Operation Breadbasket] conference in Chicago in 1966, we spoke as two mothers. In all the movies and documentaries, she is quoted as saying that she wanted the world to see what they had done to her son.

“She said, ‘No, Miss Flonzie, there was no way I was going to sit back in the quiet of the night,’” Brown Wright said. “‘I wanted the world to see what hatred had done to my son.’”

*To read the just-released records of the government’s case files on Emmett Till’s murder, go to the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection on the National Archives and Records Administration website.

Image at top: Mamie Till at the casket of her son, Emmett Till, during his funeral at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago on Sept. 6, 1955. (Credit: Chicago Sun-Times Collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images)