Editor’s note: This is the second story in the “Gullah-Geechee vs. Greed” series about the fight to preserve the last of the Black communities on these islands off the southeast Atlantic coast.

Taiwan Scott eased off the gas as he turned onto Alfred Lane in the Spanish Wells community of South Carolina’s Hilton Head Island. Overhead, stout oak trees gave a tired impression, their armlike branches stretched outward, hollows yawning through beards heavy with Spanish moss. He let the car slowly creep forward, bouncing along the narrow, pockmarked road dotted with mobile homes.

“You can tell when you’re in a Gullah community,” he said, surveying the quiet lane. “[Can you] imagine if there was a fire down here?”

It’s a far cry from the painstakingly manicured roadways that greet visitors throughout much of the island’s 12-mile stretch of prime oceanfront property. Hilton Head’s public face wears a modern aesthetic communicated in neutral tones of beige and gray, artfully landscaped traffic medians and miles of winding bike paths.

But in Spanish Wells, like many of the native islander communities, “you see the ditches,” Scott said as the car idled along. “You see the culverts. There’s no proper drainage, no sewer. All of this area floods.”

Scott is Gullah-Geechee, descended from enslaved West Africans forced to work rice and cotton plantations throughout the South Carolina Lowcountry and the sea islands that skirt the Atlantic coast from Georgia to northern Florida. The Gullah are Hilton Head’s longest inhabitants and some of its oldest property owners.

Yet they have largely been excluded from the benefits that transformed the island into a multimillion-dollar tourist destination primed to attract wealthy white vacationers and golf enthusiasts. The Southern Poverty Law Center is currently investigating how zoning and land use management policies have impacted Gullah-Geechee communities in South Carolina and Georgia.

When rapid real estate development swept Hilton Head in the 1960s and ’70s, Gullah communities were pushed aside to make way for the growth of private development — and the infrastructure to support it — from the very start. The first bridge to allow visitors and their vehicles on the island cut into portions of the historic Gullah community of Stoney, then considered the island’s commercial center. Now it barely rates a mention in the official guide to the area.

38,000Hilton Head Island’s population, of which about 75% is white and 6% is Black. That’s down from a 90% Black population in 1950.

In Mitchelville, the site of the nation’s first self-governing Black settlement, construction is underway on an expansion of the airport’s terminals and runway, tripling its capacity. After 139 years, St. James Baptist Church, which has for decades endured planes flying directly overhead, will relocate to make way. The newly constructed gas station and convenience store on the opposite side of the airport’s runway will not need to relocate.

“Since the Town’s incorporation in 1983, public infrastructure has been laid disproportionately across Gullah land, including sacred sites like cemeteries,” said Anjana Joshi, a senior staff attorney for the SPLC’s Economic Justice litigation team. “As the town develops, it expands that infrastructure at the continued expense of Gullah landowners, compounding the community’s loss.”

Meanwhile, island taxpayers have subsidized drainage infrastructure expenses for planned unit developments (PUDs) — residential areas, built on former plantation estates, where wealthy residents zip around on golf carts behind towering gates.

Yet Gullah families who want to build new homes on their land must pay upwards of $30,000 to install a fire hydrant or sign a waiver that relieves the town of any liability should a fire engulf their property, Scott said.

“I see all these fire hydrants every 500 feet on Marshland Road,” he said. “There are no houses there other than the houses in the plantation. Who paid for that? These plantations were supposed to provide their own services.”

Most egregiously, Gullah families are being priced out of the place they have called home for centuries. Decades of predatory practices have resulted in Gullah-owned land being lost to tax sales and heirs’ property disputes, or the sale of land for far less than it was worth. Zoning restrictions that do not consider the prevalence of heirs’ property or respect traditional Gullah land practices have stymied the Gullah people’s efforts to profit from their land.

The vast acreage of farmland and beachfront property once owned by Gullah people had plummeted to less than 1,000 acres in 2016, according to the SPLC’s analysis of the data.

“There is a feeling that the Gullah community has borne the brunt of development without receiving much in return,” said Joshi, the SPLC attorney. “The town’s continued failure to invest in Gullah areas of the island, to mitigate the impacts of its public infrastructure projects and to meaningfully prioritize the Gullah community’s needs and vision for self-determination has been documented for decades.”

There was once a time when Gullah islanders sought to limit development to preserve their community-driven, rural way of life. But it’s clear today that there’s no putting the genie back in the bottle. And longtime residents are finding it difficult to reap the benefits of that development.

“The town’s zoning and land use decisions and requirements make it difficult for Gullah landowners to develop their land or to recoup its true value through sales,” said Joshi. “The persistent devaluation of Gullah land, and the denial of economic opportunity, ultimately make it easier and cheaper for land speculators, including the town, to purchase or take the land.”

One obstacle after the next

Scott is a licensed real estate agent but describes himself as more of an advocate for Gullah people and culture. Most of his clients have heirs’ property, a form of shared land ownership that is triggered when a property owner dies without leaving a will — which many African Americans avoided because they feared white administrators might rob them of their property. It can be a lengthy and expensive process to clear an heir’s property title.

But without a clear title, much-needed relief for Gullah families in the form of access to beneficial loan programs, farmland subsidies and certain tax breaks remains out of reach. Heirs’ property also leaves land vulnerable to developers who can force the sale of an entire property if they can persuade one heir to sell.

Scott has had a complicated and at times toxic relationship with the town of Hilton Head since he first tried to get a restaurant business off the ground in 2015. His open-air food truck park, Beautiful Island Square, was a novel idea for Hilton Head. Located on family land in the Marshland community, it opened to customers in 2021 — six years after he first filed for his business license.

“From 1983 to 2015, not one native islander had been able to open a new business, in new buildings, on their land,” Scott said. “Ours was the first.”

When the town of Hilton Head incorporated as a limited-services government in 1983, the Gullah bitterly fought against it. Four years later, the town created its first land management ordinance with an explicit aim to curb unfettered development. But these rules did not apply to the plantations, which had existing agreements that predated incorporation.

“When we want to do something there’s always an obstacle — through zoning, through ordinances — or some type of obstacle from the town that’s prevented us from developing our property,” Scott said. “And then, eventually, the town ends up purchasing it.”

The town of Hilton Head Island, for example, currently owns the land next to his family’s Marshland property. According to Scott, the town’s staff threw every wrench they could find at him to block him from opening the business.

Things had started off well enough. His license and permits had all been approved. Then everything came to a screeching halt. The town, Scott said, ordered him to move the buildings on his property because they were too close to the property line — even though it had approved permits showing the location for those same structures.

The town complained that a cedar stain Scott had used was too orange in color. They balked at the decorative lines of small, international pennants strung up around the property and ordered him to remove them. He refused, and the flags are still flying.

When the state’s health department inspected and approved the licenses and permitting for Scott’s commercial kitchen, the town would not honor them. But it did continue taking Scott’s payments for his license renewal fees, despite barring him from operating the business.

Scott was in and out of court for years, often representing himself because he couldn’t find a local attorney willing to take his case. When he finally found representation, he ended up once again before a zoning appeals board. It approved his license. The nightmare had ended.

Zoned out

When tourists drive onto Hilton Head from the South Carolina mainland, the first neighborhood they see is Stoney — if they can catch a glimpse of its modest wooden marker as they whiz by on the 45-mph parkway. Few people abide by the limit, Scott said.

Last year, the island netted $2.8 billion in tourism revenue from more than 2.5 million visitors. Sadly, the Gullah remain virtually invisible to many of them. Many maps still fail to mark the island’s historic native islander communities. At the island’s middle and south end, where most tourists flock, few businesses or tours celebrate or acknowledge the importance and uniqueness of Gullah culture.

That got Yolawnda McKinney, a sixth-generation native islander, thinking about what she could do to serve tourists who were interested in an island experience grounded in Gullah-Geechee culture. Earlier this year, she purchased a three-story house in the Squire Pope community. McKinney later found, through historical research, that her great-great-great-grandfather Caesar Jones had owned the land in the late 1800s.

When she began reaching out to different providers seeking services such as landscaping and property management, the responses she received left her shaking her head.

“It was something to the effect of, ‘Not many homes are aesthetically pleasing on Wild Horse Road,’” said McKinney. “I was just shocked.”

A rental management company representative scoffed when she asked if they serviced homes on the island’s north end. Ultimately, McKinney had to find a company that wasn’t located on the island at all.

“It’s discrimination,” she said. “But it’s been done so long.”

McKinney said the town runs free shuttle services transporting passengers to beaches along the island’s southern Atlantic coast. But the shuttle stops mid-island, short of the Gullah enclaves.

“There are no Black communities that are serviced,” she said. “Even for locals who go to the beach — if you’re on the south end, then you have that free shuttle service. But if you’re on the north end, you do not. I just don’t think that’s right. Not when all of our tax money is going to pay for that.”

Both McKinney and Scott, as well as many native islanders over the decades, have called attention to what they see as an obvious imbalance on the island.

Many Gullah neighborhoods lack sidewalks and streetlights to illuminate walking or bicycle paths at night. There are no landscaped medians to beautify the lanes of asphalt.

One of the only remaining beaches on the north end has paid parking and lacks any other services; the lots in the Coligny Beach area on the island’s south end offer free parking and commercial activities for visitors.

The Gullah have now become the island’s Black minority, outnumbered and outpaced by the town’s new and overwhelmingly white residents. According to Data USA, an online platform that analyzes U.S. government data, Hilton Head Island’s population of nearly 38,000 people is about 75% white and 6% Black. That’s down from a 90% Black population in 1950, before the construction of the Byrnes Bridge in 1956, Joshi said.

There is an inequitable distribution of resources between communities Black and white, rich and poor, rural and urban, longtime residents say. To address the inequality, native islanders want two major issues addressed. One is making subdividing property easier, as much of Gullah land is shared between multiple heirs. The other is increasing housing density allowances and adding equitable development opportunities on the island’s north end.

Before the town’s incorporation, Gullah families were allowed to file “paper subdivisions” that allowed them to easily divide land between heirs without breaking the bank. When the town formed its limited-services government, it asked the county to stop issuing paper subdivisions, creating an exorbitantly expensive and complicated situation for many Gullah landowners. To divide a 10-acre tract into five, 2-acre parcels now, Scott said the town would require that a landowner physically have an access road in place as well as sewage, drainage and infrastructure. To tap into the low-pressure sewer line alone can cost $15,000 — or more.

Greater density — meaning the number of dwellings allowed per acre — would give native islanders the ability to extract more value from their land. The land Scott lives on in the Chaplin community, located near mid-island, is zoned at a density of four homes per acre. Just down the road, the Shelter Cove neighborhood is packed tightly with rows of colorful condominiums at a density upwards of 27 units per acre.

“I don’t really see us doing stuff like that,” said Scott. “But these homes rent for upwards of $7,000 a week. You’re holding us at four units per acre and right down the street they build at 27 units? These are the things I look at and say it’s obvious that it’s all calculated.”

Slowing the pace of development

In recent months, residents and town council members have squared off over control of the seemingly ever-growing number of short-term rentals (STRs), timeshares and subdivisions that have choked the island with traffic and, some say, threaten to destroy the island’s character. STRs generate $14 million annually in local taxes and fees on Hilton Head, and another $29 million in state and county revenue.

There are about 7,000 STRs on Hilton Head. According to the town’s data, the majority are in the south-end neighborhoods of Forest Beach (1,811) and Sea Pines (1,708), as well as Palmetto Dunes (1,409), which is located mid-island near the Robert Trent Jones oceanfront golf course.

At a council meeting in September, members discussed a possible three- to six-month moratorium on development. Residents crowded the room, many anxiously awaiting a chance to publicly comment on the proposal. Most of the speakers who mounted the podium were white, the majority working in real estate. Only one white commenter, out of more than 20 who spoke at the more than six-hour-long meeting, raised concerns about native islanders’ property rights.

“Much of the remaining developable land is heirs’ property or owned by native islanders,” said Jocelyn Staigar, reading aloud from prepared notes. “A moratorium would strip these families of their rights and their opportunity to build wealth. That is unfair, unnecessary and deeply damaging to the very people that have called Hilton Head home for the longest.”

She spoke on behalf of the Hilton Head Area Realtors, an irony that should not be lost because real estate agents make their living off of home sales.

‘Serious and permanent inequity’

In 1995, a design committee of the American Institute of Architects sent a regional/urban design assistance team (R/UDAT) to Hilton Head to devise a culturally relevant land use and development plan that would economically benefit north end Gullah residents and their communities.

The authors were appalled by what they saw as a “serious and permanent inequity” in the ways that the town had used its powers to serve the desires of plantation estate residents while refusing to extend basic services such as water, sewer, safety and road improvements to native islander communities.

“This R/UDAT is not a study of design or planning, but of a chronic failure of a town to meet its obligations,” its introduction stated. “The town is focusing the costs of remedying the problems of growth on this island, on a small, closed class of its residents — the residents and property owners of Ward 1. This policy appears to be conscious and permanent, no matter how much it is couched in words of deferral.”

Thirty years later, many native islanders would say that little has changed.

“We want to live and utilize our land openly,” Scott said. “If we want to put a mom-and-pop store on our land, we should have the opportunity to do that. If we want to put up apartments or lease our property and retain our ownership rights, we should be able to. It’s our family’s land. It’s our legacy.”

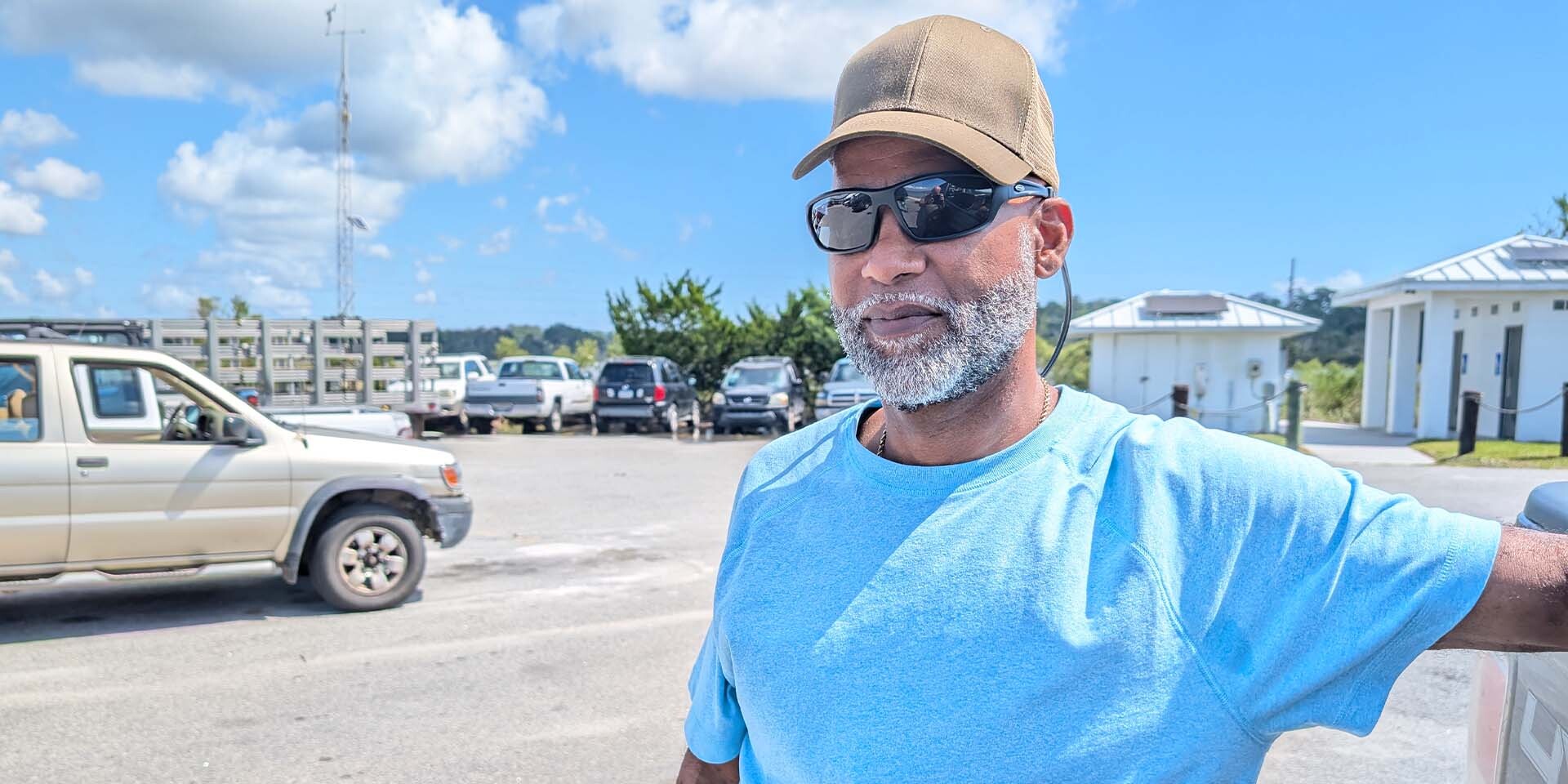

Image at top: Taiwan Scott, a Gullah-Geechee descendant, is owner of the Beautiful Island Square food truck park on Hilton Head Island in South Carolina. (Credit: Myisa Plancq-Graham)