A search for Royal, Florida, in Google Maps returns a snapshot of mostly green space speckled with pools of blue. There are two county roads — one that runs north and south, another east to west — and a prominent gray line slicing through its center, marking the route of Interstate 75.

No dotted lines appear on the map to trace the outline of this rural unincorporated community of about 1,200. But historical research has defined its place.

Located in Sumter County, the state’s fastest-growing, Royal is about an hour’s drive from Orlando, Tampa and Gainesville. It is five miles west of the growing city of Wildwood and only a few miles from The Villages, the largest retirement community in the nation with a largely white, affluent population.

Most of Royal’s 1,200 residents are descended from people who were freed from slavery when it was abolished at the end of the Civil War. Then they settled the community from the 1860s through the 1890s. Royal native Beverly Steele’s people, the Andersons, were one of three founding families who arrived in 1865. Dossie Singleton’s grandfather came that year too; and Maitland Keiler’s in 1879.

For years, the community’s boundaries have been at the center of a debate between the Florida state historic preservation officer (Florida SHPO) and the community of Royal.

As people around the United States prepare to celebrate Juneteenth, a commemoration of the moment 160 years ago when enslaved people in Texas learned of their freedom on June 19, 1865, the Southern Poverty Law Center is continuing its work, which began two years ago, to assist the community in seeking recognition from the National Register of Historic Places. The historic designation would help residents preserve their community.

Supporters can sign a petition to join in the community’s effort to be listed on the National Register.

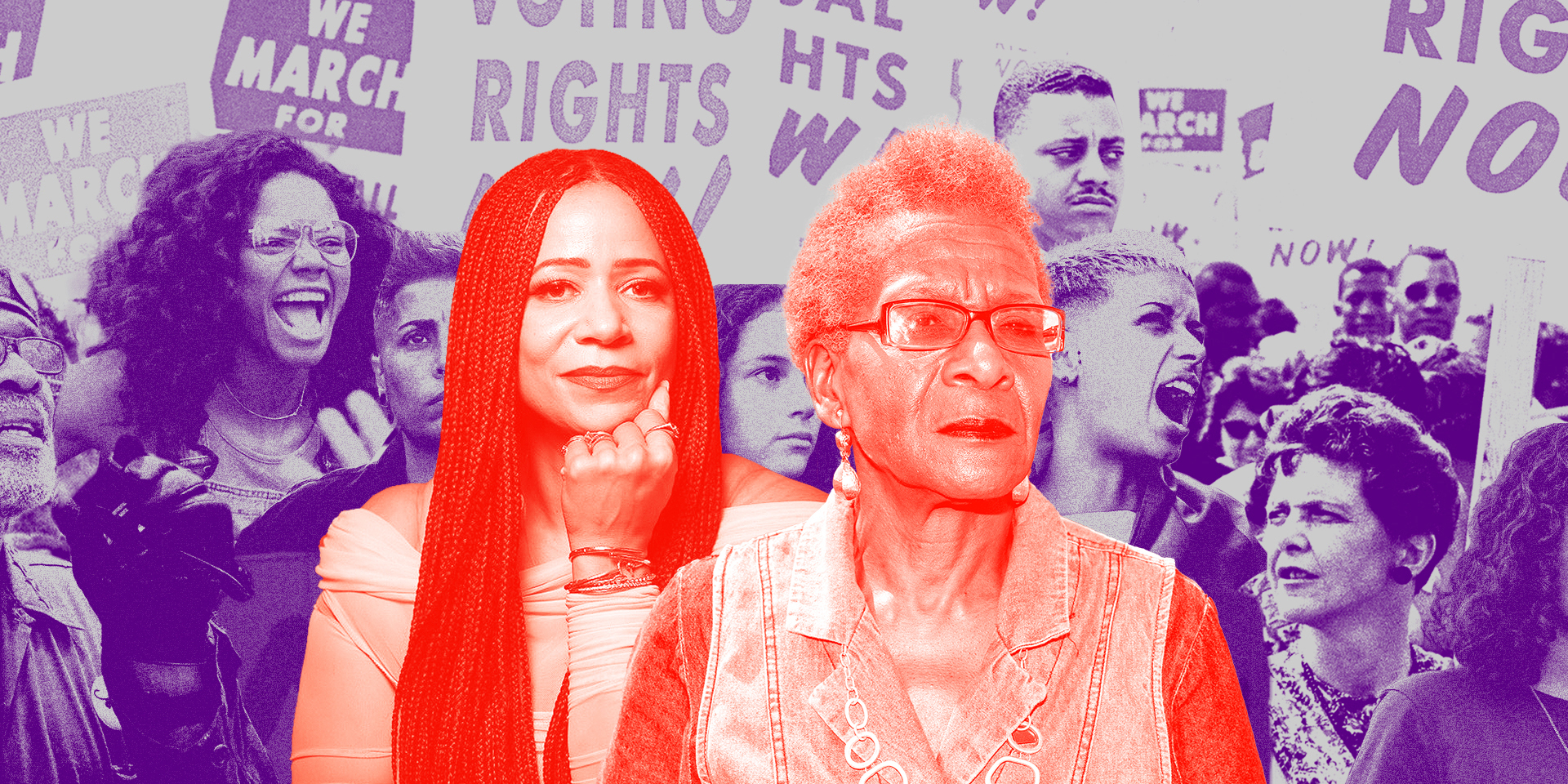

“Considering the wholesale erasure that the current administration is undertaking, it’s absolutely important for Royal to be recognized as a Black community that stood the test of time,” said Malissa Williams, a senior staff attorney with the SPLC’s Economic Justice litigation team.

The community, county and state must work together in order to successfully submit a nomination to get Royal listed on the National Register. But disagreement over its borders and misinformed notions that its recognition could limit potential land development have stalled the process.

In the video: Beverly Steele, Maitland Keiler and other natives of Royal, Florida, discuss the community’s history and their efforts to have Royal listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fighting inclusion

Royal and the historians who assessed its cultural significance have determined that the community’s boundaries span 3,501 acres. The Florida SHPO, however, has settled on 1,965 acres. That figure emerged after a small number of white developers and landowners arrived, with lawyers in tow, at a state historic review board hearing on the nomination to object to their properties’ inclusion.

In excluding those and other properties from Royal’s historic boundaries, the state has also cut out more than 20 Black landowners whose families have been in the community since the mid-to-late 1800s.

“That’s what’s holding us up now, the state and these landowners,” said Steele,the founder of Young Performing Artists Inc. (YPAs), the cultural and arts enrichment nonprofit that will submit Royal’s nomination for inclusion on the National Register. In 2015, Steele launched the effort to recognize Royal’s historic value through YPAs. At the review board hearing on Jan. 18, 2023, she said it was not made clear that the designation would not restrict property owners from developing their land.

“We’re not trying to impede on anyone’s progress, but we don’t want them to impede on our progress, either,”she said.

If the state refuses to expand the community’s acreage, Black families who have owned land in Royal for more than a century could be excluded from this historic designation because of the will of a white minority.

A centuries-old struggle

A political backlash against so-called diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) has warped discussions or acknowledgments of historical and racial injustice, branding them as divisive and unpatriotic. Attempts to erase and censor Black history from textbooks, government websites and libraries are underway. Yet Royal’s history is part of the American story, worthy of recognition.

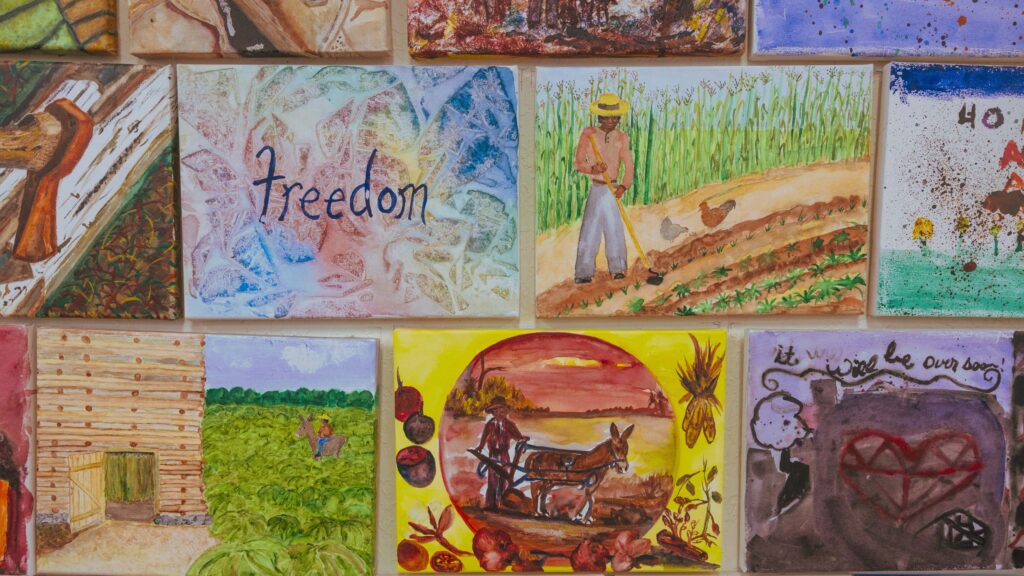

After emancipation, newly freed people traveled from plantations in the Carolinas, Georgia and elsewhere to what was then a vast wilderness of tangled brush and dense forest. They felled trees to clear the land for planting, sowed fields with crops and built homes. After five years of consistent stewardship, a process called “proving,” these Black people — who only years earlier were considered property — purchased ownership titles for their own land under the Homestead Act of 1862.

Today, 160 years after the first homesteaders arrived in Royal, the community remains largely intact. Some families have passed their land and traditions down through as many as seven or eight generations. The unincorporated town is one of only two remaining Black homesteading communities in the entire country. The other one is in Nicodemus, Kansas.

“I’ve gotten in the weeds in Florida history, and in all the books I’ve read I can’t even think of one mention of Royal,” said Nick Linville, principal and historian at Linville Historical Consulting. Linville has worked for 20 years analyzing historical research. Fifteen of those years have been focused mostly on Florida history.

Linville grew up a couple counties away from Sumter County, where Royal is located. He was hired to work on the community’s latest nomination after the previous historian, who completed its first nomination in 2021, moved on to other projects.

“When I started learning about this place, I was fascinated,” Linville said. “Royal is really unique.”

Typically, Linville said, the homesteading communities he’s identified throughout the state have been predominantly white. Something about Royal drew Black settlers in, and they kept coming. They developed a tight-knit community that at one time had its own U.S. post office, in a state that was a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan violence for most of the 20th century.

Royal’s existence stands in defiance of white vigilante mobs that terrorized Black communities from the period of Reconstruction throughout the civil rights era. It’s particularly noteworthy given the hard-won gains snatched from formerly enslaved people after the federal government abandoned its promise of “40 acres and a mule” (Sherman’s Order No. 15), nullifying their land deeds and ceding them to their former enslavers in exchange for faithless allegiance.

“You would think the white power structure in Florida would have somehow found a way to wrest this property from their hands,” said Linville. “Why didn’t that happen here? Why did Royal survive when places like Rosewood were burnt to the ground?”

Strong bonds in this close-knit community, generational inheritance of land that family members have passed on to other family members over more than a century and a half, and active historic preservation efforts have helped Royal to survive, experts say.

Bureaucratic battlefields

In 2021, Steele’s YPAs nonprofit submitted its first nomination to the Florida SHPO for review. The community and state went back and forth, each disputing the other’s assessment of Royal’s acreage. After the Florida SHPO submitted the community’s nomination to the keeper of the National Register on June 30, 2023, including only 1,965 acres, Royal sought the SPLC’s help to petition the keeper to dispute the boundaries put forth by the Florida SHPO.

Since then, the keeper has twice found in the community’s favor, describing the Florida SHPO’s boundary justification as “murky and inconsistent,” and seeking clarification on why certain historically Black-owned parcels were excluded.

When the Florida SHPO resubmitted the nomination in February 2024, the 1,965 acre-figure remained without change. In March, the SPLC, on behalf of YPAs, again petitioned the keeper, challenging the boundaries in the Florida SHPO’s resubmission. Once again, the keeper agreed that the Florida SHPO had failed to adequately justify the historic district’s boundaries and returned the nomination to the Florida SHPO to address those issues.

Then in May, unbeknownst to YPAs and the SPLC, Williams said the state told the keeper it had completed the technical edits requested and would make no further amendments to the nomination. That November — after Royal’s former historian sent its revised nomination to the Florida SHPO in September — the state notified him it was taking no further action on the nomination.

Despite this, YPAs has been working with a new, SPLC-hired historian on a third nomination that it plans to submit to the Florida SHPO this summer.

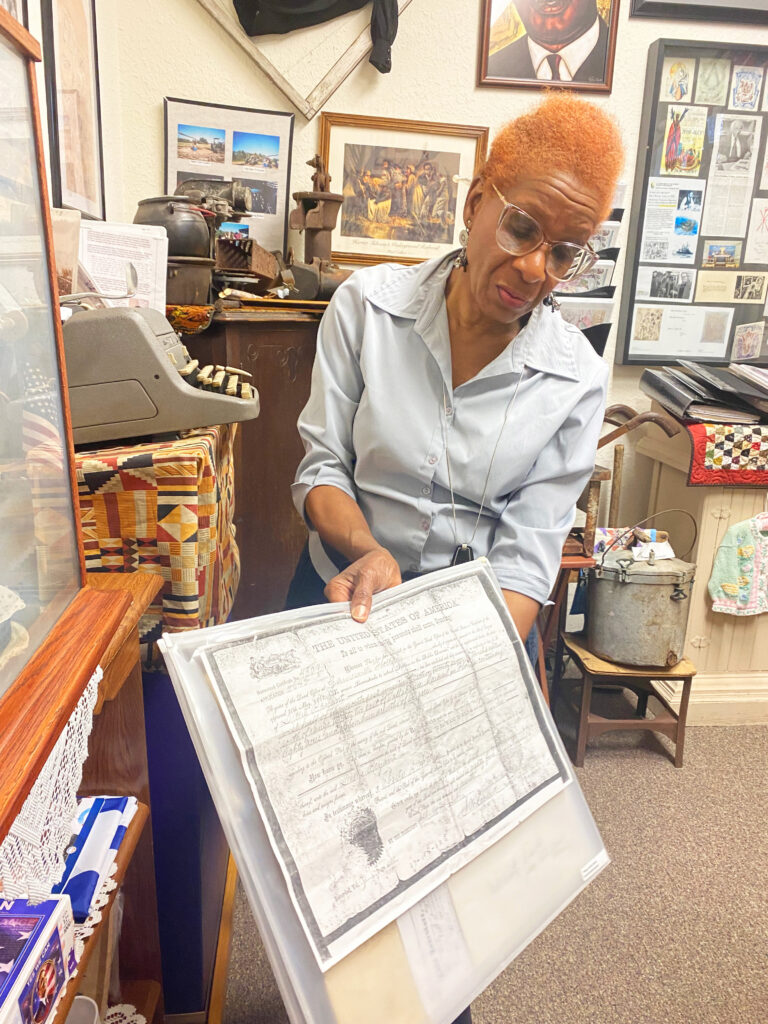

Clockwise from top left: Beverly Steele, founder of Young Performing Artists Inc., displays a copy of an 1885 land deed for property in Royal, Florida; Maitland Keiler shares a newspaper clipping about the SPLC’s Civil Rights Memorial; and Keiler is pictured again at the Alonzo A. Young, Sr. Enrichment & Historical Center in Royal. “Our people went through something to get this land,” Keiler said. (Credit: Malissa Williams, Saúl Martínez)

Progress, the destroyer

Royal was not exempt from the targeted interstate highway construction that occurred during the late 1950s through the early 1970s. That work economically and culturally gutted many once-thriving Black neighborhoods that these road-building projects either severed or completely absorbed.

In 1969, Florida’s I-75 split Royal down its middle. Yet the community persisted.

“Blood, sweat and tears,” said 92-year-old Maitland Keiler, looking through thick, black-rimmed eyeglasses that magnified the weight of his stare. “Our people went through something to get this land.”

Dressed in a white polo jersey and crisp, light-blue jacket, Keiler sat at a folding table in the Alonzo A. Young, Sr. Enrichment & Historical Center. The center is a wellspring of community history with newspaper clippings, artifacts and memorabilia dedicated to Royal taking up every inch of available space. The building is on the site of the former one-room school that he and all the residents over 60 years old who were educated in Royal attended before it was closed during the 1969-1970 school year, when integration was enforced.

Royal’s cultural and historical significance is a point of pride for the community. Residents know that development is inevitable. But after more than 100 years of stewardship, they feel they’ve earned the right to have a say in how that development plays out.

“Land is wealth in this country,” said Williams, the SPLC senior staff attorney. “Royal is located in the fastest-growing county in Florida, and I think the county and state are concerned about anything that might impede development in the area.”

But, Williams said, “I think what’s gotten lost in this process is that having an area designated as a historical district does not preclude property owners in that district from putting commercial or industrial development on their land.”

What it does require is that projects that receive federal funding or permitting follow Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. It requires the federal agency issuing a permit or funding to take account of the cultural and historic assets within the boundaries of the development and engage with the community about what mitigation efforts it can take to avoid harming those assets.

“Anything at the local, county or state level that doesn’t have federal funding attached to it does not trigger Section 106 review,” Williams said.

Hoping for healing

At an evening community meeting in April, members of the University of Florida Law Environmental and Community Development Clinic presented a review of the county’s laws and local government structure with its recommendations to residents gathered in the vast sanctuary of New Life Center Ministries Church.

The law school students presented different options for land use, development and zoning, laying out the benefits and drawbacks of each for the community and its preservation efforts. Through zoning, Royal could have more involvement in shaping its future, from noise control to traffic and commercial enterprises, but that could require a change in governance.

After the presentation, Steele projected a map onto the screen to show the state’s proposed boundaries for an upcoming project to widen I-75.

“I want everyone to be aware of what’s happening,” she said.

On June 14-15, Royal will hold its annual homecoming celebration. The community’s population swells with family and friends of Royal who do not take for granted the peace, quiet and communal living the century-plus-old rural Black settlement offers. This summer, YPAs will submit to the Florida SHPO Royal’s latest nomination to the National Register.

With history on its side, the community is hoping this time the state will be, too.

Image at top: Beverly Steele, founder of Young Performing Artists Inc., at the Royal, Florida, cemetery. Steele’s ancestors were among Royal’s founding families. (Credit: Saúl Martínez)