In the opening scenes of The Quilters, a 30-minute short film Netflix released last year, a man named Ricky wheels a pallet of quilted blankets and fabric swatches past high barbed wire fencing. Another man, wearing a gray uniform shirt, unspools bright orange thread wrapped around a silver bobbin. Yet another drops the presser foot of a sewing machine onto a piece of fabric to keep it taut and steady.

Five days a week, from 7:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., a handful of men gather in a room crammed with fabric and sewing tools at the South Central Correctional Center, a state-run Level 5 maximum security prison in Licking, Missouri. Together they design and sew birthday quilts for children living in foster care in the surrounding communities.

The outreach is part of a restorative justice project that focuses on healing and accountability. Some of these men have spent decades behind bars. Others may never again live outside the prison’s walls.

For many in the program, quilting for these children has become their greatest joy.

“A lot of these kids were told they would never amount to anything, that they’d never be any good,” said Jimmy, a member of the quilting program. (The last names of the program’s participants were withheld.) “For them, this is my chance to give them something to say, ‘Hey, we care about you.’”

This month, the Civil Rights Memorial Center (CRMC) and the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Alabama state office invited community members to view a screening of the documentary and to consider the common misconceptions society holds about people behind bars.

“The Quilters shows that decarceration begins with recognizing the humanity that we overlook,” said Lauren Blanding, manager of the CRMC in Montgomery, Alabama. “Restorative justice matters because accountability without healing only repeats harm. Restoration gives people a chance to become more than their worst moment.”

Across the United States, almost 2 million people are currently incarcerated within the criminal legal system. According to statistics from the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2016, the average person serving a sentence had received less than 11 years of education. Almost two-thirds of people in state prisons had not completed high school, while more than half of people incarcerated in federal prison had not earned a diploma.

In the Deep South, the incarceration rates in Florida and Georgia are among the highest in the country. A disproportionate number of people imprisoned in these states are Black. While Black residents make up only 15% of Florida’s population, in 2021 they accounted for 48% of people held in state prisons and 41% of those held in jails. In Georgia, Black people represented only 31% of the state’s 2021 population. At the same time, 59% of the people locked in prisons and 51% of those jailed in the state were Black.

The SPLC works to end unjust imprisonment, overcriminalization and discriminatory laws and practices that target and harm Black and Brown people in such Deep South states.

Beyond concrete walls

In many prisons, there’s limited access to restorative justice programs like the quilting project in Missouri. To work as part of the program at Licking, the men must have no violations or write-ups. Space is limited.

To these men, the time spent in service of others is invaluable. It offers them a chance to express emotions beyond the tough instincts required to survive within the prison’s concrete walls.

“This environment, it’s a jungle. So, I got to be a little more rough around the edges,” said one of the quilters, known as Chill, about the atmosphere at the maximum security prison. “I’m the big bad wolf down here. But I gotta be or they’ll eat you alive. That’s just the way it is.”

Chill first learned to sew as a teenager doing upholstery work. He has spent eight years in prison, with six more to go — serving 14 years for a first-degree assault conviction.

“But it’s a front,” he said of his hard exterior while speaking about the quilting program. “Because up here, like, my emotions change when I walk through the door.”

Throughout the film the men discuss their different strategies for laying out quilt patterns, how they arrange the 3,500 pieces of fabric required to create the large blankets and the design choices they make.

Fred likes to incorporate bold colors. Jimmy favors stars. Chill loves butterflies because they remind him of his mother.

They are also frank about their previous mistakes and the harm they have caused to others and themselves.

“I’m guilty for what I did,” said Ricky, a quilter the men admire for his vast knowledge and ability to fix just about anything in the sewing room. For him, quilting brings back memories of childhood, when his mother and grandmother would quilt, sew and patch up the family’s hard-worn clothes. He first entered prison at 20 years old. He is now 64, serving a sentence for a murder conviction.

“After a while you get thinking about your family,” Ricky said. “And then when you get thinking about them, then the truth really comes out. Wow, all the stuff I did.”

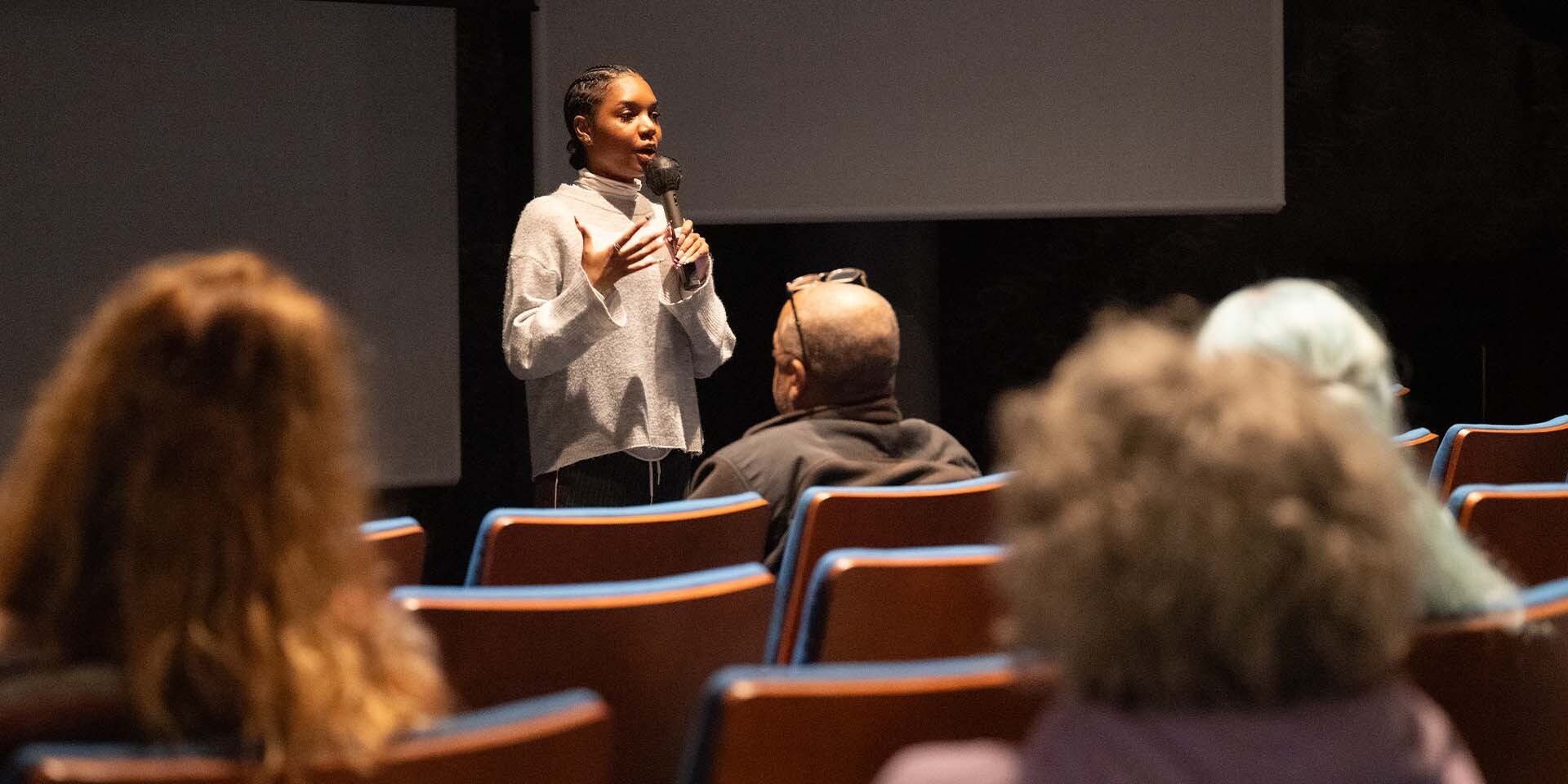

The film raises a range of questions, notably about redemption and self-worth, justice and accountability. After the screening of the documentary, SPLC Alabama state office organizer Makhayla DesRosiers led a brief discussion during which audience members shared their thoughts and emotions.

Some considered the connections between the foster care system and prisons, as research has shown that children and youth who have lived in foster care are more likely to end up in the criminal legal system. A 2021 DOJ study reported that 18% of people in state prisons and 10% of those in federal prisons have spent time in a foster home or institutional care.

Some noted the positive impact the restorative justice program had on the quilters’ mood and sense of self by allowing them to do for others. Audience member Shatara Clark noted the importance of community members showing support directly to those imprisoned. She runs a nonprofit, TyTalks, that holds weekly visits, in partnership with a local nonprofit, C.H.A.N.G.E., with women in Alabama’s Montgomery County Jail to discuss the process of reentering society. C.H.A.N.G.E. stands for Connecting Hands by Accommodating Necessary Growth for Everyone.

“Showing up and being persistent is so important,” Clark said. “Using the resources that you have to be a part of the solution.”

Others said they felt a greater sense of empathy for the imprisoned men.

“At the start of the movie, one of the guys said that we want to show the kids we care,” DesRosiers said. “I thought that’s just so symbolic, because who’s making sure that they show these men that they care about them? It’s kind of like pouring from a cup that’s empty.”

Toward the end of the film, the men smile as they pass around a thank-you card with two pictures enclosed of children posing with their birthday quilts. Jimmy staples them to a bulletin board, where they join a collection of letters and drawings praising the quilters for their efforts.

Image at top: Makhayla DesRosiers, senior community organizer for the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Alabama state office, speaks during a discussion that followed a screening of “The Quilters” on Dec. 9, 2025, at the Civil Rights Memorial Center in Montgomery, Alabama. The documentary spotlights men incarcerated in a Missouri prison who sew birthday quilts for children in foster care in nearby communities.