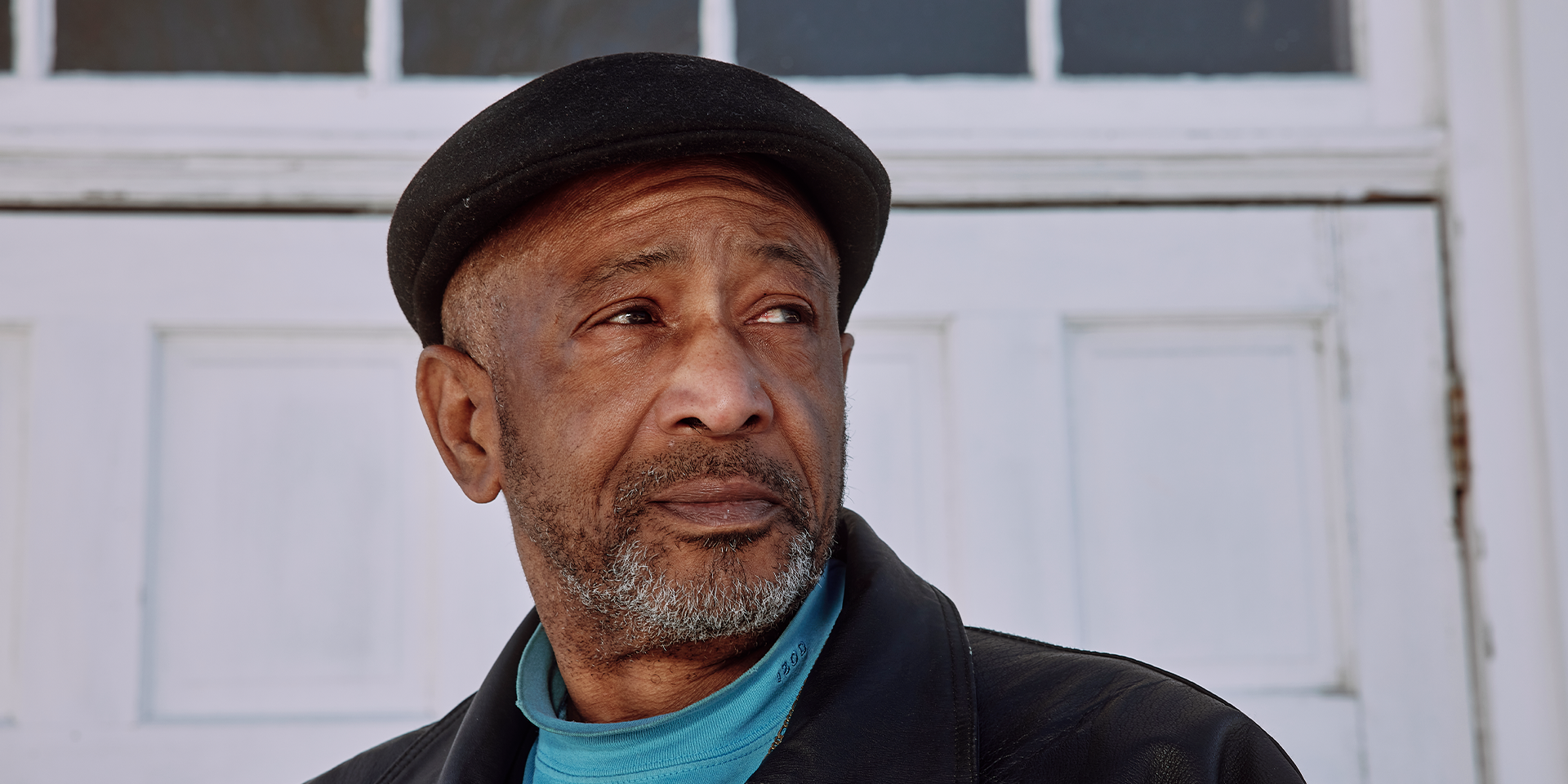

Vincent Carter, 72, has lived his entire life in Gum Springs, Virginia. The town is within walking distance of George Washington’s Mount Vernon — an estate where Carter’s ancestors were enslaved — and Woodlawn, another historic plantation-turned-museum built on 2,000 acres taken from the original Mount Vernon property.

“My great-great-grandfather on my mother’s side guarded Washington’s tomb,” Carter said, adding that his maternal great-grandfather and great-grandmother worked inside the Mount Vernon mansion. “My 91-year-old mother, 94-year-old aunt and my uncle were all born at Woodlawn.”

In 2023, Carter accompanied Woodlawn’s then-executive director on a private tour to solicit Carter’s ideas for new programming that would radically alter its public history. At that time, the museum had already begun to create exhibits which included more significant stories about the people enslaved at Woodlawn as well as the mid-19th century free Black community established there after Quakers took ownership of the plantation. This was a shift from the traditional focus on Woodlawn’s original owners, Eleanor “Nelly” Parke Custis Lewis (Martha Washington’s granddaughter) and her husband, Lawrence Lewis.

“When I walked into the basement, I could feel the spirits of people who I knew worked there,” Carter said of the storage space in the basement, which he visited on his private tour that day.

While he was there, he also discussed what he thought the tour should say about the storage space and how it should look.

“You just can’t fix the top [of the mansion],” he said. “My people were slaves in the kitchen. I want to make sure they show that true story, too.”

Woodlawn unveiled its new permanent exhibition, “Woodlawn: People and Perspectives,” in May 2024. It became one of a number of historic home museums in the U.S. that share an expanded history of the enslaved Black people who lived and worked on their grounds. Instead of discussing Nelly’s musical talents, tour guides ask visitors, “How do you feel when you’re in this space?”

“We encourage visitors to have these uncomfortable conversations,” said Elizabeth Reese, senior manager of public programming and interpretation at Woodlawn. “Especially today, historic house museums are one of the last places where strangers can come together and have these difficult discussions.”

Tour guides no longer tell “Lost Cause” stories of lavish dinners served on bone china or exhibit decorative trappings of the Lewis family’s genteel lifestyle as the National Trust for Historic Preservation did for more than 70 years.

The exhibition still includes paintings of Washington, but tour guides ask visitors to consider how these paintings marginalized people who were enslaved there. They point out how printers intentionally removed images of enslaved laborers from lithographs of paintings to preserve the public’s polished image of the first president.

Enslaved Black people built and maintained the property — and the pampered lifestyle — of their enslavers. Wedge-shaped bricks, made by hand for Woodlawn’s exterior columns, are silent reminders of their toil. A family wedding dress contrasts the experience of the owners with that of enslaved seamstress Sukey, who likely reworked the dress in the 1830s for a new Lewis family bride.

“Many historical sites tend to present only one side of the story and often avoid addressing the negative aspects of history that might be uncomfortable for some visitors,” said Julian Teixeira, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s chief communications officer, who toured the site last year. “In contrast, Woodlawn is willing to be bold and provide an accurate representation of history, rather than glorifying our legacy of slavery.”

Starting from scratch

Eighteen months of intensive research and planning predated the revised Woodlawn exhibition’s opening. Staff consulted with historians, descendants of the property’s Black and Indigenous communities, the museum’s advisory council and other partners to determine the new exhibition’s goals. They also selected exhibits and found primary sources to back up the tour and make the history accessible to all.

That history took a new direction after Lawrence Lewis’ death. The estate sold the property to two Quaker families, the Troths and Gillinghams, in 1846. Their mission was to prove to enslavers that farming could be profitable without slavery. They sold plots to numerous descendants of Washington’s formerly enslaved laborers from Mount Vernon, who gained their freedom when he died in 1799.

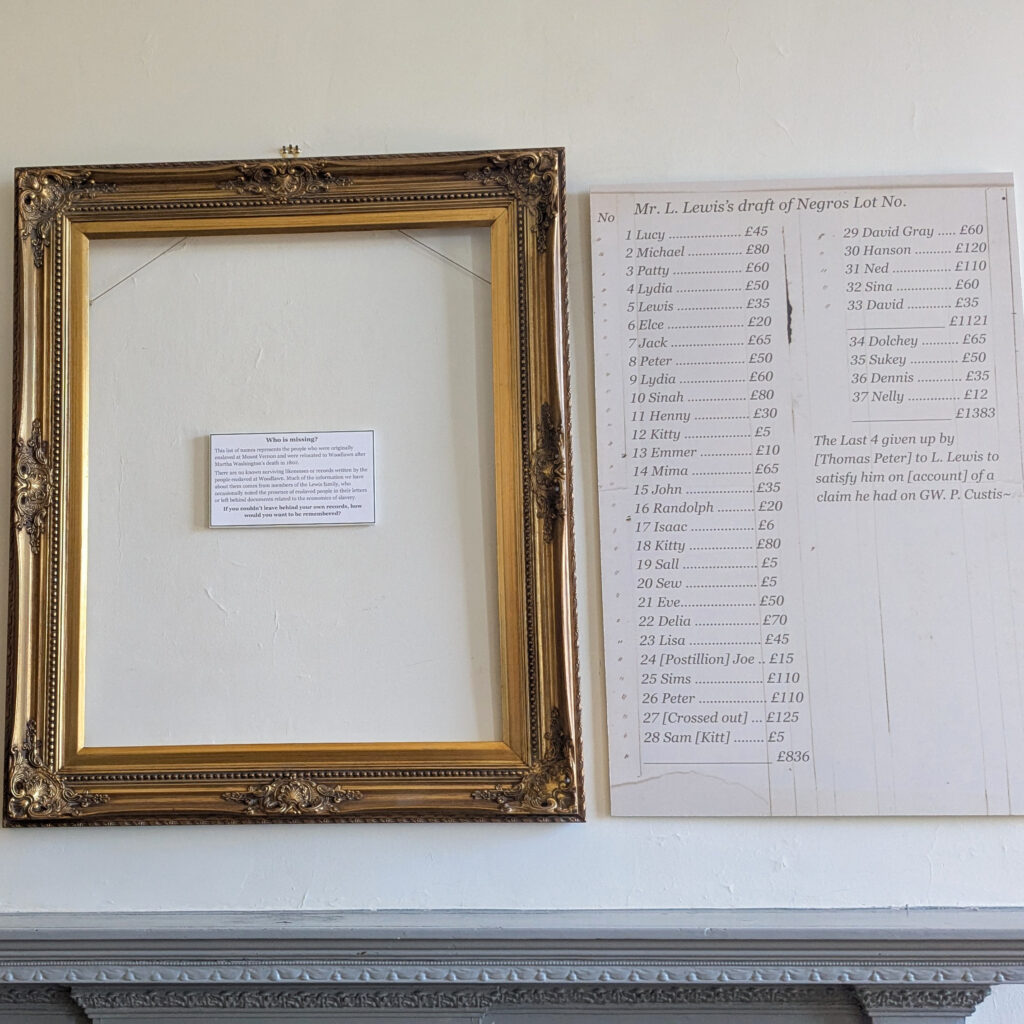

More than 90 people had been enslaved under the Lewis family’s ownership of Woodlawn. According to the 1820 census, more than half were children. But they were gone when the Quakers arrived, having been sent to plantations in the Deep South or to another Lewis plantation in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

The Quakers taught the farmers sustainable agricultural methods to rehabilitate soil that had been degraded after decades of single-crop use. They also taught the new plot owners how to read and write, violating Virginia law of the time.

“It was a prosperous community,” Carter said. “The Quakers proved that Blacks could assimilate and prosper in a Southern state.”

Like those early farmers, Woodlawn museum staff had to start over to create a more honest and relevant permanent exhibition.

“At the time, we had no collections staff, no interpretation, no marketing to look at the underrepresented histories of Woodlawn and ensure that their stories could be told,” said Heather Johnson, Woodlawn’s deputy director of finance and operations and former interim executive director. “What the Quakers did was so radical. Unlike the previous owners, the Quakers stood in opposition to the social and economic norms of the region.”

Woodlawn began to transition away from the Lewis story in 2018, when the museum introduced temporary exhibits showcasing aspects of its Black history. Visitor reactions were mixed.

“Twenty to 25% of respondents to a survey we conducted in 2018 said the new information impeded their experience of the house,” Johnson said. “Others thought it was an interesting way to engage audiences in a different way. Our point of view was that it enhanced the experience.”

In 2020, museum staff expanded the narrative to include information about all Woodlawn owners, not just the Lewises, but research was still needed to include a larger lens on the enslaved community.

‘A change in perspective’

With grants received to specifically research the history and displacement of the enslaved population at Woodlawn, a revamp was possible in 2024.

In 2025, staff updated the museum’s website with a comprehensive history of the property and its inhabitants built from primary sources. It also hosted a program in which historians and storytellers described the lives of the enslaved people at Woodlawn and other Virginia plantations.

By the end of 2025, the museum had 18,300 annual visitors, exceeding pre-pandemic levels. New visitors accounted for 50% of the site’s special programs, pointing to the public’s embrace of the more truthful history.

“Over the past seven years, there has been a change in perspective,” Johnson said. “The way we are telling history now is more open-ended. People can take it in and ruminate on what they have learned.”

Rivka Maizlish, a senior research analyst for the SPLC’s Intelligence Project, said house museums are especially suited to teaching adults and children accurate U.S. history. The Intelligence Project tracks Confederate symbols, “Lost Cause” propaganda narratives and ideologies of white supremacy for the organization’s Whose Heritage? project.

“The U.S. has only a few museums dedicated to the experience of the enslaved, and it’s a shame that there aren’t more,” Maizlish said. “There is an immediacy to be in the space where history happened and where students can learn about enslavement, abolitionism, resistance and the Civil War without classroom pressure.”

Research flips the story

The research of independent historians Susan Hellman and Maddy McCoy into Woodlawn’s Black and Quaker history, which began around 2010, may have preordained Woodlawn’s new direction.

A direct descendant of original Quaker co-owner Jacob Troth, Hellman grew up near Mount Vernon. Her grandfather’s family is buried in the cemetery at Woodlawn’s Quaker Meetinghouse, built between 1851 and 1853.

Hellman knew Troth’s history at Woodlawn from childhood. As the museum’s deputy director in 2010 and acting director until 2013, she documented the site’s history through the end of Washington’s ownership.

McCoy’s research focused on Woodlawn’s Black history, which she had begun researching in 2005 as a college intern in the Fairfax County Library. Eventually, she built a database that is now housed at the Fairfax County Historic Records Room.

“I saw a real need to uncover and identify the names of formerly enslaved individuals because there was a gap in the records,” McCoy said. “It was by design. African American individuals weren’t considered worthy of recordation by name, in official documents.”

McCoy realized that the history of Woodlawn’s enslaved families was often hidden in the record of white families, predominantly in their probate records. Using those records allowed her to rebuild that history and reclaim it.

Her research underpins the new story of Woodlawn. It acknowledges the deep trauma in all aspects of life that the enslaved people of Woodlawn and their descendants suffered. And it allows the descendants to finally know the full story.

Image at top: Vincent Carter of Gum Springs, Virginia, offered ideas to update the programming of Woodlawn, to better represent the enslaved people who built and maintained the property. (Credit: Jared Soares)