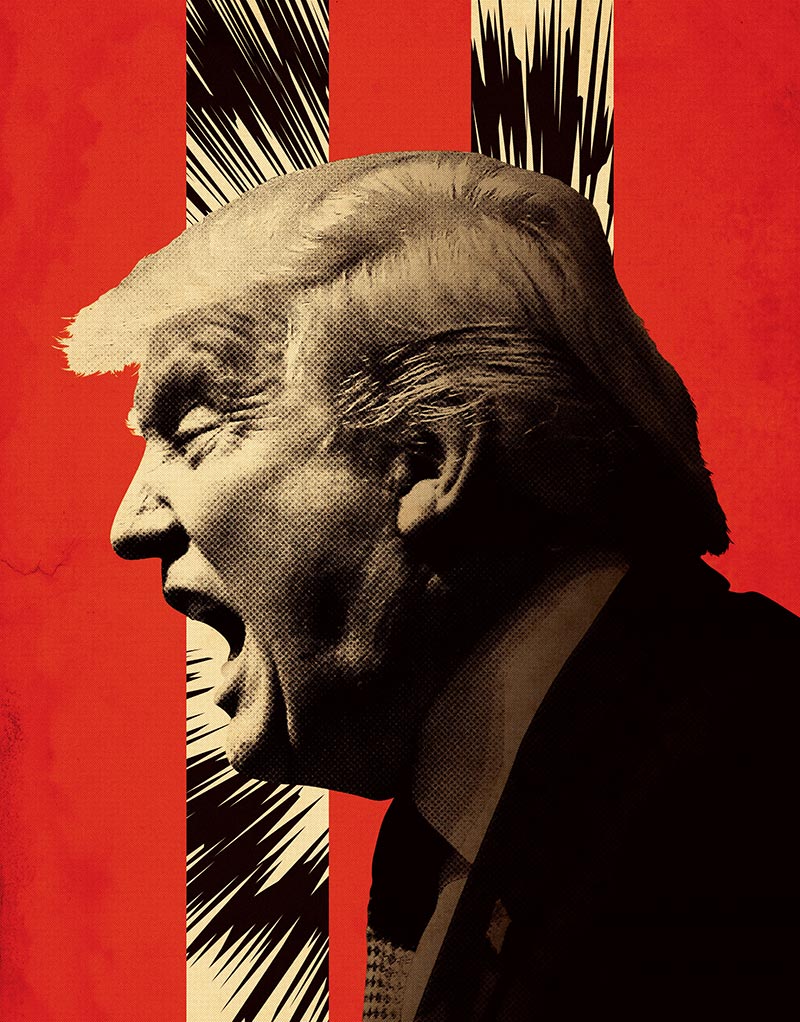

The campaign language of the man who would become president sparks hate violence, bullying, before and after the election

In August 2015, two Boston men returning home late after a Red Sox game happened upon a homeless Mexican immigrant sleeping outside a commuter rail station. They beat him with a metal pipe, punched him repeatedly, urinated on him and called him a “w——.” Then they high-fived each other as they walked away, leaving Guillermo Rodriguez with broken ribs and fingers and other injuries.

When they were arrested a short time later, one of them, 38-year-old Scott Leader, told arresting officers, “Donald Trump was right. All these illegals need to be deported.” Later, but long before they were sentenced to terms of two and three years, they whined that authorities only arrested whites, “never the minorities.”

To these men, Donald Trump was a hero — and an inspiration.

After all, Trump had kicked off his presidential bid two months earlier with a speech describing Mexican immigrants as rapists and drug smugglers. He later called the Mexican government “totally corrupt.” He promised to build a wall along the 2,000-mile Mexico-U.S. border. He told an audience in New Hampshire that a plane overhead “could be a Mexican plane up there, they’re getting ready to attack.” And he insisted that an Indiana-born federal judge could not preside fairly over a civil racketeering case against his Trump University because “he’s a Mexican.”

And that was just Trump’s talk about “Mexicans.”

By the time he won the election, Trump had called for a “total and complete shutdown” of Muslims entering the country. He had lied about personally witnessing “thousands” of Muslims in New Jersey cheering as the World Trade Center collapsed on 9/11. He had attacked a Muslim Gold Star family, insinuating that Khizr Khan, whose son died in Iraq, was a terrorist sympathizer. He had retweeted utterly bogus claims that black people were responsible for 80% of the murders of whites. He had cozied up to some of the country’s hardest line gay-bashers. He had retweeted anti-Semitic memes and called many immigrants “not well.” He had attacked a debate moderator by insinuating that her tough questions were the result of her menstrual cycle. And his earlier boasts about grabbing women by the genitals had been revealed.

Trump also had repeatedly encouraged violence.

After a Black Lives Matter activist was beaten at a Trump rally in Birmingham, Ala., he told Fox News that “maybe he should have been roughed up.” In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, he urged supporters to “knock the crap” out of protesters, adding, “I promise you, I will pay your legal fees.” When a backer at a Fayetteville, N.C., rally sucker-punched a black protester being led away by police — an act described by the local sheriff as “a cowardly, unprovoked attack” — Trump told two national news outlets that he was looking into paying the man’s legal fees.

Through it all, Trump was heedless, rejecting calls from left and right to tamp down the insults and the violence they were spawning. His reaction to the beating of Guillermo Rodriguez was typical. While the attack was “a shame,” Trump’s main conclusion was that “people who are following me are very passionate.”

Taking Stock

In the immediate aftermath of the election, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) noticed a dramatic jump in hate violence and incidents of harassment and intimidation around the country. At the same time, a wave of incidents of bullying and other kinds of harassment washed over the nation’s K-12 schools. The SPLC decided to make an effort to document all of this in real time.

The ugly evidence of hatred unleashed had already become apparent before Election Day. An earlier SPLC study of the impact in K-12 schools of Trump’s bigoted rhetoric and encouragement of violence during his campaign had found massive anecdotal evidence of a rise in bullying and anxiety in classrooms.

There was even evidence that Trump’s attacks on Muslims during 2015 — when he called for a ban on Muslims entering the U.S., suggested a registry for Muslims already here, and proposed to surveil mosques — had had an effect that early. The FBI reported that anti-Muslim hate crimes went up by 67% in 2015, while other categories rose only slightly. It seemed obvious that Trump’s rhetoric, along with Islamic State atrocities, had driven anti-Muslim hatred to new highs, with the 2015 anti-Muslim hate crime count registering the highest number since 2001.

These trends only worsened after the election.

In its post-election first study, looking at harassment and intimidation in the first 10 days after Trump’s election, the SPLC counted 867 hate incidents, some of them amounting to hate crimes, around the country. It collected information from media reports, social media, and through a #ReportHate page set up on the SPLC website, excluding incidents found to be hoaxes.

The results were disheartening.

“I have experienced discrimination in my life, but never in such a public and unashamed manner,” an Asian-American woman reported after a man told her to “go home” as she left a train station in Oakland, Calif. A black man whose apartment was vandalized with the phrase “911 n—–” said that he had “never witnessed anything like this.” A Los Angeles woman, who encountered a man who told her he was “[g]onna beat [her] p—-,” said she had been in the neighborhood “all the time and never experienced this type of language before.” Not far away, in Sunnyvale, Calif., a transgender person reported being targeted with slurs at a bar where “I’ve been a regular customer for three years — never had any issues.”

Incidents were reported in nearly every state. The largest portion (323 incidents) occurred on university campuses or in K-12 schools. The incidents were dominated by anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim incidents (together, 329), but included ones that were anti-black (187), anti-Semitic (100), anti-LGBT (95), anti-woman (40) and white nationalist (32). A small sliver of them (23) were anti-Trump, but the vast majority appeared to be celebrating his election victory.

When the SPLC first released these findings, right-wing media outlets claimed that there was no evidence that they were related to Trump or the election. But that is false. For one thing, the largest number of incidents occurred on the day after the election, and they declined fairly steadily for the nine days after that.

Later, when the SPLC updated its findings to cover the first 34 days after the election, it counted a total of 1,094 bias incidents around the nation. Importantly, it also calculated that 37% of them directly referenced either President-elect Trump, his campaign slogans, or his infamous remarks about sexual assault. Just 26 were anti-Trump, with six of those explicitly anti-white.

Particularly noteworthy in this longer period was a string of letters, describing Muslims as “Children of Satan” and a “vile and filthy people,” sent to 15 mosques and Islamic centers around the country between Nov. 23 and Dec. 2. Also during that period, there were 57 incidents of extremist posters and flyers appearing, about three-quarters of them at university campuses, where emboldened white nationalists have been hard at work since the election. Thirty-four campuses were hit.

Hate Goes to School

The SPLC’s first, pre-election look at bias incidents in K-12 schools was based on responses from about 2,000 educators. In its post-election survey, however, the SPLC got responses to its online survey from more than 10,000 teachers, counselors, administrators and others who work in schools. Although the survey was not scientific, with such a large response it was hard to dismiss the findings.

Ninety percent of the respondents said that the climate of their schools had been affected negatively by the election. A full 80% described heightened anxiety on the part of students worried about the impact on them and their families. There were reports of slurs, derogatory language, and incidents involving extremist symbols.

Eight in 10 educators reported fears on the part of marginalized students including immigrants, Muslims, African Americans and LGBT people. Four in 10 heard derogatory language directed at minority students. More than 2,500 described instances of bigotry and harassment directly related to election rhetoric. Two out of 10 had heard derogatory comments about white students, although few of them were made directly to those students. Most were remarks about whites voting for Trump.

An Arizona high school counselor reported white students holding up a Confederate flag in a school assembly. A middle school teacher in Washington told of a student blurting out in class, “I hate Muslims.” A Georgia high school teacher said many students were making jokes “about Hispanic students ‘going back to Mexico.’” Another teacher in Oregon described a black girl running out of a classroom in tears after being racially harassed in two classes. A Massachusetts middle school teacher described how a white student, on the day after the election, went around asking each non-white student he passed, “Are you legal?”

“This is my 21st year of teaching,” a Georgia elementary school teacher reported. “This is the first time I’ve had a student call another student the ‘n’ word. This incident occurred the day after a conference with the offender’s mother. During the conference, the mother made her support of Trump known and expressed her hope that ‘the blacks’ would soon know their place again.”

Words Have Consequences

Four days after the election, Donald Trump was interviewed on “60 Minutes,” where he was asked about the hate. He said he was “surprised to hear” about it, and, looking into the camera, told the perpetrators to “stop it.” In another interview, he promised to “bind the wounds of division” that were afflicting our country.

His comments were a day late and a dollar short. The hatred, and the new energy of the white nationalist movement, were predictable results of the campaign Trump waged — a campaign marked by incendiary racial statements, the stoking of white racial resentment, and attacks on so-called “political correctness.”

A few weeks later, Trump acknowledged what he had not earlier. In a post-election speech in Orlando, Fla., part of his “thank you” tour, he responded to the crowd chanting “Lock her up” with this: “Four weeks ago, you people were vicious, violent, screaming, ‘Where’s the wall? We want the wall! … ‘Prison! Prison! Lock her up!’ I mean, you were going crazy. I mean, you were nasty and mean and vicious and you wanted to win, right? Now, same crowds … but it’s much different. You’re laid back, you’re cool, you’re mellow. You’re basking in the glory of victory.”

Donald Trump is not legally responsible for any of this, of course. The people who engaged in legally punishable hate violence, if they are caught, are the ones who will have to actually pay for their crimes. But it seems undeniable that Trump’s reckless, populist campaign has left a legacy of hatred, violence and division.