After almost three violent decades in the racist movement, Lynette Avrin called it quits. In an interview, she describes her life and her decision to abandon racism.

Barely into her teens, Lynette Sonya Avrin was drawn into the skinhead movement in the early 1980s in Denver, which at the time was a real hotbed of racist activism. An angry young woman who felt that her parents essentially abandoned her, Avrin witnessed an enormous amount of violence and experienced a good deal of it herself. She also knew some of the most infamous activists of the era. But after she had two children and a long series of bad experiences with her supposed friends, she began to have doubts about her ideology and lifestyle. The turning point, she says, came in 2009, when a confrontation with a neo-Nazi boyfriend landed her in the hospital and terrified her then-10-year-old son. Today, she is raising that son in Colorado. Avrin, now 45, contacted the Intelligence Report after spotting an article about women on the radical right, “Secrets of the Sisterhood,” that mentioned her in the Report’s Spring 2013 issue. She wanted to tell her story and to explain how completely she now rejects the racist movement. In the following interview, Avrin discusses how she came to join the movement, what it was like, and why she finally left.

Lynette, can you start by describing your early life in the Denver area?

Sure. I was adopted by a Jewish family at 6 weeks old and grew up knowing that I was adopted. My mom and dad had three biological sons but my mom wanted girls, so she actually adopted me and my sister.

My parents got a divorce when I was 4, and I remember it. That was the point in life where I think I basically started getting angry. My mom had custody of us but we were pretty much brought up by nannies and housekeepers or my brothers. She was never around. She was out dating men or whatever she was doing. I remember her bringing home a man who she dated for years. I really liked him, but he had a cake in one hand and a kitty in the other, and I’m thinking, “Who is this guy and why is he trying to bribe us? You’re not my dad, you know.”

I was a pretty wild child. I was one of those kids who was brought home by the Arapahoe County Sheriff’s Department — even at age 4, I would run away. I usually just went to a neighbor’s house to play, but I didn’t tell anyone.

My dad got custody of us finally when I was around 10, and then he told us, “Hey, I’ve got a new girlfriend.” It was my mother’s ex-best friend.

They had housekeepers take care of us, too, because if they weren’t working, then they were traveling to Europe. So we had another set of parents that weren’t really around. And here comes my dad telling me what to do and I’m like, “Where have you been?”

What was your dad like?

He was a physicist and a scientist, a very smart man. He built an instrument called a nephelometer that measured the surface of Jupiter. He’s retired now, and my stepmother passed away about a month ago. I haven’t really spoken to him in probably 15 years.

We didn’t have the best relationship. He would tell me, “You’re grounded,” and I basically would say F you, and I was gone. I wouldn’t listen to him. At around 12 or 13, I got into the whole punk rock scene in downtown Denver. I had the Mohawk and all that stuff and then I started to get interested in the skinhead thing. That’s when they were pretty big in Denver.

Eventually, he was like, “I give up. Do whatever you want.” That’s not what I wanted to hear, but I decided to do what the hell I wanted and I did.

Were either of your parents racists?

No, not at all. There was no racism in our house. I think I was just so full of hate for other reasons that I thought, “These skinheads are totally right.”

Once, when we were at a restaurant, there was a black guy and a white girl and my mom said, “I’m sure her parents must be thrilled.” But that was the only time I heard anything like that. My parents told me as I got older, “You don’t have to take on the Jewish religion — just respect our religion. You can be whatever you want.”

What was attractive about the skinheads?

I didn’t feel like I had any control in my life. But as a skinhead, people were afraid of me. I mean, I was all of 4-foot-9, and people were afraid of me. It made me feel like I was in control, like I had some power.

I thought this is my family and these guys are going to take care of me forever. It was just like creating another family. I really didn’t feel like I had a family because I was adopted, and I felt at the time that they just didn’t like me very much.

I didn’t get a lot of the ideology stuff, but we did get a lot of the violence. I’d hear, “Negroes cause all this crime, Mexicans are all coming over here to our country.” They’d say, “Jews are taking over the whole country,” and I’d think to myself, “But my parents are Jewish and they don’t act like that at all.” I was like, “I don’t understand,” but of course I was young, so I was like, “Okay. I get it, yeah.”

They didn’t really educate us as to why they felt that way. It was all about violence, “Let’s go see who we can beat up tonight.”

I don’t really think in my heart that I truly hated anybody. I just think I got involved and they kind of brainwashed me and it went on like that.

What kind of violence did you experience then?

When I was young, skinheads would beat up other, newbie skinheads. You had to prove you were really a skinhead. I remember a huge skinhead girl who had a much smaller one on the ground, saying, “Lick my boots.” I didn’t want to get in the middle because I liked them both. But I should have stood up for my smaller friend. When it was over, she said, “Thanks,” and she never really talked to me again.

There were what people called “boot parties.” They’d take somebody and five or six skinheads would just kick the crap out of them, kick them in the face. Once up in Boulder, there was an Asian girl with a white guy and a bunch of people I was with just beat the crap out of them. They had the guy against a car and were just punching him in the face with brass knuckles. They got away with it, too.

You left Denver after high school, right?

Yes, right after high school. I moved out to Grandview, Mo., with a skinhead guy. The scene out there was different. They had SHARPs [Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice] and “straight-edge” skinheads [straight-edgers, who can be racist or non-racist, oppose all drug use], and we all kind of meshed. We used to go see shows down in North Kansas and drink beer and stuff. But we never went out and beat people up and there wasn’t much discussion of race. It was kind of a neat little group that we had.

After Missouri, I went back to Colorado for a while and was back hanging out with the Denver Skins. I used to hang out with one notorious skin there in particular. We’d drink beer on the front porch, and these little black kids would be running around laughing at us, and we’d chase them with a fire extinguisher. “Let’s see if we can paint them white,” you know. We didn’t actually catch up with any of them. But we had rocks thrown through our window, we had Crips checking out our house and following us home.

What happened next?

A bunch of us got the idea in our heads to move to Florida because some skinheads came up from there. It was like, “You know, there’s nothing here in Denver, this scene is kind of shot.” I ended up staying down there for a year. It was a pretty violent scene. We would go out and look for anti-racist skinheads and beat them up.

I remember driving down the street and one of my friends was like, “Hey, look at that f– over there. He looked at me funny.” They beat him up so badly that he couldn’t identify any of the people there. It was a bad scene.

I was in Florida for about a year and then accidentally ended up in Albuquerque, N.M. We were in Nashville, Tenn., going to beat up the lead singer of a band — I don’t even remember why we didn’t like him — and our car broke down. Here comes this van with Mark Kowalski waving at us. [Editor’s note: About a year later, in July 1993, Kowalski led a racist terror gang that bombed an NAACP office in Tacoma, Wash., as part of a plot to start a race war. He was sentenced to almost 12 years in prison.] We ended up with them driving across the country, getting stopped every chance a cop had.

Mark is an extremely violent psychopath. Everywhere we went, if someone was playing their music loudly in a car, he would smash the window and beat him up with a crowbar.

You had some rough times in Albuquerque.

The worst thing happened there when we went to a 7-Eleven on a Sunday. We wanted some beer, and Mark smashed the case and we all grabbed beer and took off. We were drinking and, the next thing I know, there were these two Native American guys, and one had a gun. I don’t know what started the fight but the next thing I know one of our friends was on the back of a Native American man beating him in the head with a ball-peen hammer. Then they beat the guy with his own gun. We were all dragged down to the homicide unit, but they let us go. It was so bad, the violence was starting to get to me at that point.

Another time, we went to a show and Mark had a knife in his flight jacket that I had no idea about. There were a lot of SHARPs there, and Mark got up and grabbed the microphone and said, “I’m a white nationalist skinhead. Anybody got a problem with that?” Of course, they did. I was outside with a girl drinking, and he’s inside stabbing people. The entire club started emptying out and somebody punched Mark in the head. We jumped in a friend’s car and, like in a movie, the car died in the middle of the crowd. We had about 100 angry skins jumping on the car.

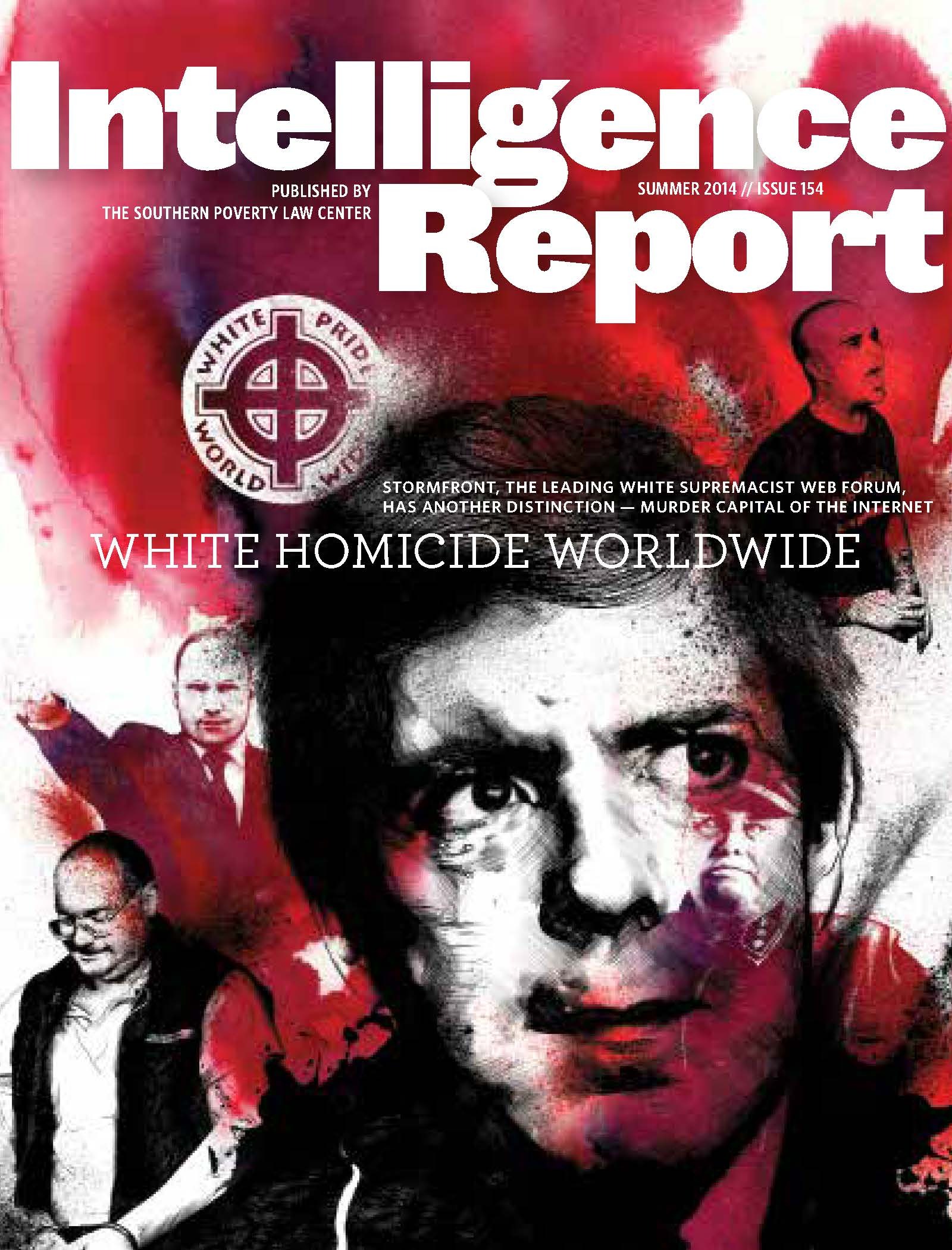

The police came and took Mark off to jail. I went to Arizona for a little while, but ended up going to back to Albuquerque, where I met my daughter’s father. I lived there for about 10 years. I grew my hair out and stayed away from the whole skinhead scene. My daughter was born there in 1993, but went to stay with her grandparents for a really long time. My son was also born in Albuquerque, when I was 27. It was when he was a baby that we got our first computer. I got hooked on Stormfront [the world’s largest racist Web forum], White Aryan Resistance [another racist website]. I wasn’t really doing anything between 1999 and 2008 except posting on Stormfront. That’s where I got my “education” — they throw these statistics [about race] at you.

Eventually, we moved back to Colorado. Unfortunately, my husband was an alcoholic and that’s what caused our divorce. Through Stormfront, I met this guy, Jeromy Drumm, who was in California. I thought he was this great guy. [Editor’s note: Drumm was a member of the neo-Nazi National Alliance.] In 2009, my mother passed away and I decided to move out to California to live with this guy. My son and I brought our cats out and everything. My daughter was living with her father.

The Alliance was the first group you formally joined, isn’t that right?

Yes. We used to have a monthly meeting at a secret place, some restaurant. We’d go to gun shows and pass out literature, talk about getting white nationalists to run for congressman or something. I met Jim Ring [the Alliance’s Sacramento unit leader] and also got to know Erich Gliebe [the Alliance’s national leader].

What was Gliebe like?

I spoke to him on the phone a few times and that guy is really slimy. He finds these women and sends them text messages about how pretty they are, then asks them out on dates. He kind of reminds me of Lurch. He was more interested in seeing how quickly he could get me into his bed than anything else.

And how did it go with Drumm?

Jer’s mother abandoned him when he was three and he has a deep hatred for women. But he can be very charming.

It started with little things. He tried to blame these little marks on our wooden floor on my son. One day the butcher knife disappeared. Then my cats started disappearing. It took me a while to recognize how crazy he was. I think he was planning to do something to me and my son.

One day, I was talking to a friend on Facebook and I called him “sweetheart.” Jeromy went insane. He had already basically taken $6,000 my mother left me. He said, “You need to leave,” and I said, “I think we will.” But I told him I needed like four days because I had no money and was waiting on child support.

The night before I was supposed to leave, I was on the back porch smoking and he said, “You know what? When you’re daughter turns 18, I’m going to have her come live with me.” I spit in his face. He was basically telling me he was going to bring my daughter to his home and do things to her.

He pushed me so hard I flew probably three feet. Now, Jeromy is six feet, maybe a little taller, and about 215 pounds, and I’m 125 pounds and 5-foot-2. He grabbed me and was carrying me sideways through the house, smashing me along the walls. He threw me in the bathroom and tried to lock me in there. I stuck my hand through the door and he slams this metal door on my arm probably 10 times. I had this huge contusion, and told my son, who was 10, “Call the police right now.” He comes out and sees my arm and, oh, Lord, it was bad. It was horrible.

And what happened?

While we were waiting, Jer is videotaping me and calling the police himself and telling them that he had been assaulted, because he banged his head on a door and had these two little scratches on his forehead. Later, he went on Facebook and basically said I was a drunk, I was horrible to my child, I’m the one that beat him up, and that I was a “cop caller.” And all these people who had been my friends for all these years believed him.

When the police arrived, their basic thing was, “Well, hey, you’re leaving, you’re going back to Colorado, so we aren’t going to press any charges.” They took me to the hospital. When I got out about four in the morning, my son and I took a cab back and Jer had my Jeep all nice and packed for me.

We ended up in a domestic violence shelter in Colorado and then in transitional housing for a few years.

So how did your break with white nationalism finally happen?

I realized that nobody I knew really cared. I thought I had this family all these years. That’s obviously a complete lie, because they don’t care. They’ll turn their backs on you in a split second. They’ll stab you in the back.

They claim that “we love our race,” that it has nothing to do with hate. But it has everything to do with hate. I was realizing that I don’t want my children to grow up this way. I saw my friends teaching this to their children at age three. What does a child know about hate? Their parents think it’s okay to teach them that, and I don’t think it’s okay at all. Even when I was a skinhead, I always told my son, “You be friends with whoever you want.” I didn’t push my beliefs on him.

He never wanted anything to do with it. And he’s a great kid. He just started a new school and he’s in ROTC. He’s got not one hateful bone in his body. I mean nothing. He’s got Hispanic friends. He’s got black friends. He’s got Jewish friends. And my daughter was married to a Hispanic man, a very, very nice guy.

There are other reasons. These white nationalists glorified it when Trayvon Martin was killed. [Editor’s note: Martin was shot to death in 2012 by a white Florida man who claimed he felt threatened by the unarmed, black 17-year-old.] It was huge. I actually went on Stormfront and said, “How dare you celebrate the death of a child?”

I said, “You know what, I don’t need this because I don’t believe in it any more.” That was the end of it and I was done.

Lynette, what would you say to young people flirting with white nationalism?

I would tell them, “Don’t do it. It’s so stupid, why would you want to do this?” But when I think about it, when people would say things like that to me, I was like, “F you. I’m going to do whatever I want.” It’s sad, but maybe they have to find out on their own. If they can’t find a positive mentor in life, then they may be stuck on that same road that I was on for years no matter what people said to me.

I honestly wonder, would people listen to me if I went to a school and said, “You know, I used to be a skinhead”? It’s hard to say what I would say to them. You can try and say really honestly that this isn’t a smart path to go down. I could tell them that half the people I knew are dead or in prison. I don’t know what I could say. I did it the hard way. I had to find out for myself.

It amazes me now that we’re in 2014 and prejudice and racism still has not gone away. With gay marriages and other things, it should be gone. I tell my son I don’t care if somebody is gay. So they are gay. Let them be married.

It’s been a really long road, but now I’m done with it. Carrying around hate your whole life is just not healthy. It can make you sick. How can somebody claim to love themselves if they hate people? You need to just look at people as people. That took me a long time to figure out, but I’m pretty glad I did.

Interview conducted by Mark Potok.