Following the tragic 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, school districts across the country grappled with the question: “What makes a school safe?”

Many school districts responded by creating or expanding their law enforcement programs or placing school resource officers (SROs) on school grounds and at school-related activities.

Law enforcement officials were first placed on school campuses in the early 1950s. Today, 41 percent of the nation’s public schools report having an SRO on their campuses, and this number is on the rise. Though the presence of law enforcement in schools has been increasing, there is no evidence that school-based law enforcement make schools safer. Due to a lack of data, inaccurate data, and challenges in accessing data on school policing programs, it is impossible to adequately evaluate SRO program effectiveness.

Sound data on school policing programs is needed: 1) to measure the effectiveness of these programs and determine whether taxpayer dollars should be funneled into creating or expanding them; 2) to help evaluate whether schools are complying with federal anti-discrimination laws; and 3) to measure whether schools are safe and welcoming for all students. In the absence of this information, anecdotes – while helpful in rounding out the picture – are the primary influencers of school policing policy, not rigorous research.

While school-based law enforcement duties vary across school districts, the primary responsibility of officers on campuses is law enforcement. SROs, however, have also been increasingly called upon to respond to school disciplinary incidents, resulting in harsher consequences for minor misbehaviors by students.

Schools are required to collect and report data on key education and civil rights issues – including school policing data such as the number of students referred to law enforcement, the number of students arrested at school-related activities, and the number of sworn law enforcement officers (including SROs) in their district – to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR), which is charged with enforcing certain federal anti-discrimination laws in schools.

What’s more, school districts and state departments of education are required to publish data on school policing under the Every Student Succeeds Act. Though Louisiana has school data collection laws, these laws have not caught up to federal requirements for the collection and publication of certain student data, including school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement and the presence of SROs in Louisiana’s schools.

Through research and public records requests, the SPLC found that local school districts are not accurately and consistently collecting data on their school policing programs, and the data that was collected and reported had discrepancies compared to data reported to the OCR and data collected by law enforcement agencies. This suggests that educators, families, and policymakers lack accurate, basic information about school policing in the state. The Louisiana Legislature should require schools, school districts, and the Louisiana Department of Education to accurately collect and publicly report data on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement as already required by federal law.

Photo by Melissa Golden/Redux

An introduction to school policing

On Feb. 14, 2018, a former student of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, was dropped off by an Uber at the school shortly before dismissal. He carried a duffel bag and a backpack. Less than seven minutes later, Nikolas Cruz had fatally gunned down 17 staff members and students and wounded 17 others.

Mass killings make up less than 1 percent of gun deaths in the United States, and of these incidents, only an average of one takes place in the school setting per year (here, a mass shooting is defined as one with four or more fatalities). However, it only takes one tragic school shooting to strike fear in the hearts of parents and students alike. After the Parkland shooting, the Pew Research Center found that 57 percent of American teens reported being in fear of an active shooter incident happening at their school, and 63 percent of parents shared their concerns.

In the wake of Parkland, communities and schools across the nation are once again exploring how to ensure school safety. In November 2018, The Washington Post reported that the market for school security has grown to $2.7 billion, as schools clamor to implement measures that purport to further school safety. These attempts have often come in the form of increased surveillance, metal detectors, and clear or mesh backpacks – regardless of whether the research supports the measures. However, many schools and school districts have opted for sworn law enforcement officers – or school resource officers – on their campuses as a strategy to increase school safety.

The History of School Policing

The origin of school policing programs can be traced back to the 1950s. Research indicates that the first assignment of a law enforcement officer to a school occurred in Liverpool, England, in 1951. In the early 1950s, the Flint Police Department in Michigan was the first known law enforcement agency in the United States to place an officer on a school campus full-time. The officer was tasked with deterring and responding to violent crimes on school grounds and working to foster a better relationship between local law enforcement and youth. The term “school resource officer” was not used to describe a law enforcement officer placed at a school until a Miami police chief coined the term in the 1960s.

Flint’s program led to the establishment of programs in other states such as Arizona, Florida, and North Carolina in the 1960s and early 1970s. By the 1970s, school districts sought to create their own police departments, due to legislation allowing districts to establish departments under their direction. During this time, just 100 SROs were reported to be scattered across 1 percent of U.S. school campuses.

School resource officer programs gained national legitimacy in 1973 with the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals’ support of their use. The commission recommended that law enforcement agencies annually conduct a presentation on the role of the law enforcement officer in society, and recommended that agencies with over 400 officers assign officers full time to senior and junior high schools in their jurisdiction. In the same decade, the Florida Legislature mandated that SROs be placed on all middle and high school campuses.

SRO programs got another boost when political scientist John Dilulio Jr. introduced the concept of the juvenile “super-predator” to the American consciousness amid the spread of broken windows policing, a concept that promoted policies designed to crack down on teenage drug use and violence in the mid-1990s. Despite teen crime and violence being on the decline throughout that decade, the perception of rising adolescent criminality only heightened the concern within school districts.

As a result, the number of law enforcement officers in schools skyrocketed. In 1991, the first national convention of school resource officers was held in Sarasota, Florida, and the inaugural board of National Association of School Resource Officers was established. By the mid-1990s, over 2,000 SROs had been placed on school campuses throughout the country – a 1,900 percent increase from the 1970s.

The passage of the Safe Schools Act of 1994 and the 1998 amendment to the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 further incentivized the placement of law enforcement in schools by allowing the allocation of federal money for these programs. Fear of high-profile school shootings – such as the 1999 Columbine High School shooting – further fueled the expansion of these programs.

In recent decades, school resource officer programs have grown, particularly in urban school districts. In the early 2000s, Congress authorized the departments of Justice and Education to provide millions of dollars for the implementation of school policing programs in hundreds of communities – including $68 million from the Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS).

Federal funding for school policing programs briefly declined after 2005, following the 2005 termination of the COPS’ Cops in Schools program, which

awarded federal grants for school security personnel, and the expiration of the Safe and Drug Free Schools and Communities Act in 2009. Federal funding picked up again after the 2012 school shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. The U.S. Department of Education noted a surge in the number of SROs in schools during the 2013-14 school year, and 42 percent of all public schools reported having a full or part-time school resource officer during the 2015-16 school year.

Within this climate, it appears these programs are more likely to expand than downsize.

The role of school resource officers

While one of the fastest growing areas of law enforcement is school policing, the role of law enforcement in schools is unclear. The duties, responsibilities, and titles of law enforcement vary across school districts, and stakeholders have yet to reach a consensus regarding their role.

SRO responsibilities are typically outlined in agreements between schools and law enforcement agencies often referred to as memoranda of understanding. Overall, the primary responsibility of officers on school campuses is law enforcement.

SROs, however, have been increasingly called upon to step outside of these duties and respond to school disciplinary incidents, resulting in unnecessarily harsh consequences for students. The growing involvement of SROs in disciplinary matters has been linked to increased arrests of students for minor misbehavior and disproportionate arrests of black students on school campuses.

The current state of school policing in Louisiana

Louisiana law defines a school resource officer as a “peace officer,” the duties of which include responding to crime, making arrests, and conducting searches and seizures. After Parkland, many Louisiana school districts attempted to expand school policing programs. Some parishes, including the following, succeeded:

Bossier Parish

After forming a committee with members of Bossier Parish School Board and community members to address school safety after Parkland, Bossier Parish Schools increased funding to add five SROs to its high schools in August 2018.

Lafayette Parish

In July 2018, Lafayette Parish School System tripled its funding for SROs. To afford the $4 million program, the school board reorganized the district’s central office and cut some positions.

St. Tammany Parish

St. Tammany Parish Public School System elected to have SROs at all 55 of its school campuses for the 2018-19 school year, costing $2 million to support this initiative, along with additional funding to provide mental health services in its schools. These measures arose from the school superintendent convening a group of parents, administrators, teachers and others to discuss security measures.

Some efforts were unsuccessful. In November 2018, Livingston Parish voters considered a $5.5 million sales tax proposal by the school district and local sheriff’s office, to place SROs on each Livingston Parish public school campus, and to provide these officers with equipment that included firearms and stun guns. The proposal failed as 56 percent of voters opposed it.

Through such referenda and discussions about SROs at school board meetings, Louisiana communities are engaged in the debate about law enforcement in schools and its impact on student safety – a debate whose importance has only been underscored by the Parkland shooting. Yet, this dialogue is occurring without the benefit of publicly reported – and accurate – data.

A look at data collection

Public school districts are legally obligated to collect and publicly report data on school quality, climate and safety – including school policing. Through the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC), the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights requires public school districts to collect data verifying that districts are adhering to certain federal anti-discrimination laws. The Every Student Succeeds Act imposes the additional obligation on school districts – as well as state departments of education – to collect and publicly report CRDC data.

Collection of school data under the CRDC

The Office for Civil Rights is responsible for enforcing federal civil rights laws that prohibit discrimination in programs or activities that receive federal money from the U.S. Department of Education. These federal laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability status, and age.

As part of its federal civil rights enforcement and monitoring strategy, since 1968, the Office for Civil Rights has required school districts to collect data on issues relating to education and civil rights and to submit this data to the office. This mandate is known as the Civil Rights Data Collection. The Office for Civil Rights publishes this data collected by school districts to the general public, biennially (every two years). The CRDC’s most recent survey, released in the summer of 2018, contains data collected from every public school district for the 2015-16 school year.

Specifically, school districts are required to collect information on enrollment and school characteristics, early childhood education, college and career readiness, student discipline (including types of discipline used, bullying and harassment, and restraint and seclusion), and staff and resources. They are required to collect the following information about school policing:

• The number of K-12 students who were: 1) arrested in the course of school or during a school-related activity or; 2) referred to a law enforcement agency or official in the course of school or during a school activity (“school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement”). School districts are required to break this information down by race, sex, disability status and English learner status.

• The number of school resource officers in schools.

The Every Student Succeeds Act

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) imposes an additional obligation on public school districts to collect and publicly report CRDC data, including school policing.

The ESSA is a federal statute that authorizes the U.S. Department of Education to provide financial assistance to school districts under the statute’s nine titles to enhance academic achievement for disadvantaged children. ESSA Title I, Part A grants are allocated to each state’s department of education, to be distributed to eligible school districts for programs designed to increase academic achievement for low-income or minority children.

Each state and school district that receives a Title I, Part A grant must prepare annual “Report Cards” that include measures of school quality, climate, and safety – including data on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement agencies. The Report Card must present school policing data in the same way that such data is submitted to the Office for Civil Rights – broken down by disability status, race, sex, and English learner status.

This requirement is significant because the ESSA makes some CRDC data – including school policing data – available to the public annually, rather than every two years, which is the case with the CRDC survey. The Louisiana Department of Education receives Title I funds from the ESSA, which means Louisiana public school districts must include school policing data in their annual report cards.

The need for good school policing data

As school districts continue to increase the number of school resource officers, collecting and publicly reporting data on their impact on students and school safety is critical. Schools must collect and report school policing data under federal law. As discussed earlier, public school districts are required to collect and report, at a minimum, data on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement on an annual basis. But there are other reasons data about school-based policing is needed:

• There is not enough data to know if school policing is effective.

A recent congressional report on school resource officers noted, “There is a limited body of research available regarding the effect SROs have on the school setting.” The lack of research evaluating the effectiveness of school policing programs is attributed to a lack of data and difficulty in accessing what little data there is available. At best, the research that exists offers conflicting evidence on the efficacy of school based policing. At worst, there is no evidence that school resource officers are effective.

• Schools are accountable to taxpayers.

As of 2013, estimates placed the cost of having armed security at every school in the United States as much as $23 billion. As states and school districts consider funding school policing programs, it is important to keep the public informed to ensure tax dollars are spent effectively and responsibly.

• School policing data is an important measure of school quality and climate.

School climate is described as “the quality and character of school life.” A positive school climate is crucial to better academic outcomes and the beneficial development of youth. School safety is an important aspect of this climate that includes physical and socioemotional security as well as discipline.

Does Louisiana comply with laws and regulations?

The methodology

To gauge compliance with federal data collection and reporting obligations – as well as whether districts are keeping adequate data to measure program effectiveness – the Southern Poverty Law Center sent public records requests (Appendix A) to eight Louisiana school districts in the “Florida Parishes” region. These requests focused on the presence and use of law enforcement officers in schools for the 2015-16, 2016-17 and 2017-18 school years.

Through news stories and the SPLC’s work, we learned of an active presence of law enforcement in the region’s school districts, making it ideal for study. The surveyed school districts are Bogalusa City Schools, Livingston Parish Public Schools, Northshore Charter School, St. Helena Parish School District, St. Tammany Parish Public School System, Tangi Academy, Tangipahoa Parish School System, and Washington Parish School System.

To compare and measure the accuracy of the data reported by these school districts, the SPLC sent public records requests to 33 law enforcement agencies located within the parishes of the selected school districts (Appendix B). The selected school districts and law enforcement agencies were surveyed on the existence of school policing programs and memoranda of understanding; policies and procedures regarding law enforcement in schools; training requirements for school-based officers; data on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement; and for school districts only, any additional security measures on school campuses.

The SPLC requested records from the school districts and law enforcement agencies in February 2018. Generally, the Louisiana Public Records Act requires a recipient of a public records request to provide written responses no later than three business days from the date the request was received. However, in an effort to obtain full and accurate responses, the SPLC devoted hundreds of hours to corresponding with school districts and law enforcement agencies from Feb. 23, 2018, to Jan. 4, 2019.

The findings

When the SPLC undertook its survey, it found these school districts are not accurately and consistently collecting data on their school policing programs. As

a result, the SPLC – or any researcher – cannot measure the effectiveness of these school policing programs due to scarce data and limited means to verify its accuracy. As the detailed findings below demonstrate, until these failures are addressed, it is not possible to fully assess the quality, climate, and safety of Louisiana’s public schools.

A majority of school districts surveyed were unable to provide complete data on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement.

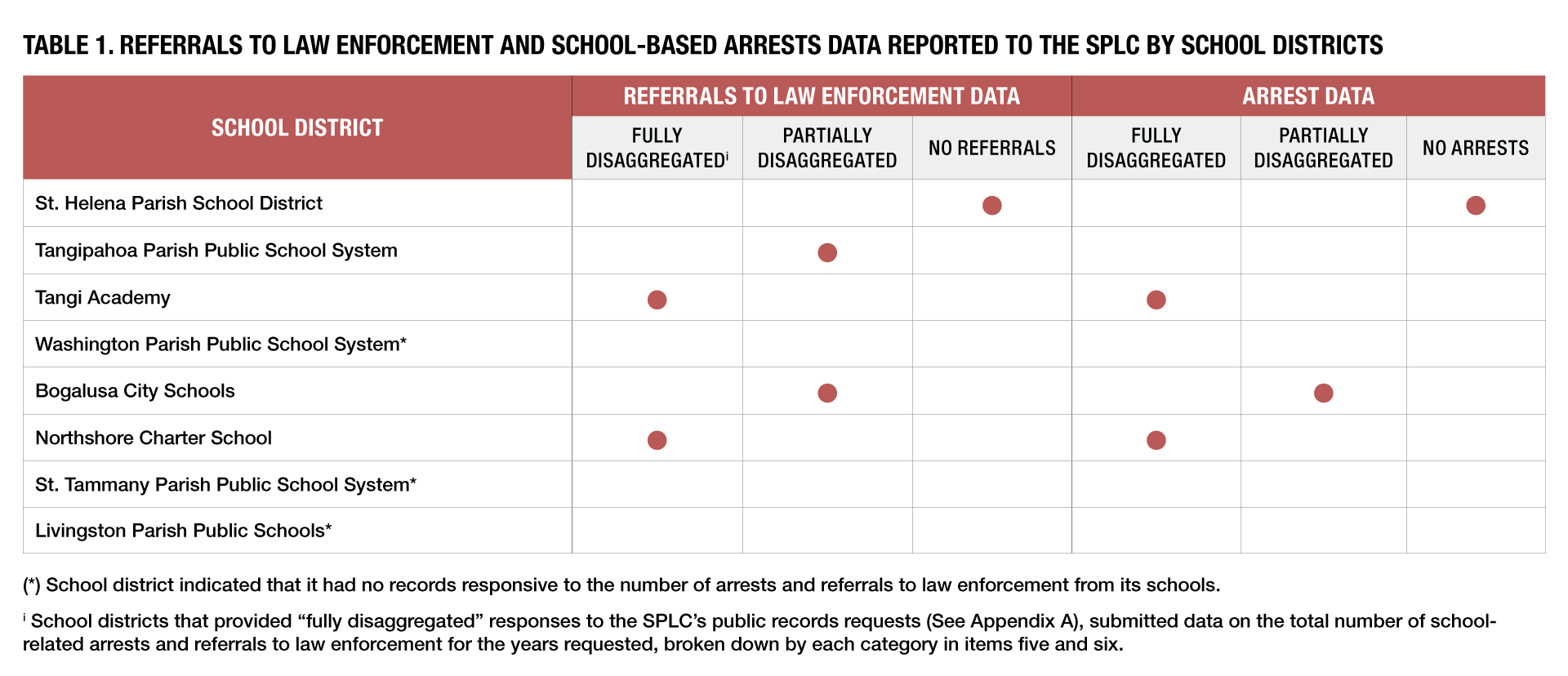

• Of the eight school districts surveyed, only two produced fully disaggregated data on the number of arrests and referrals to law enforcement for the years requested.

• Two school districts provided partially disaggregated data for the years requested.

• Three school districts said they had no records on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement. Washington Parish School System responded: “The option to document arrest data became available March 2018 so we have begun documenting arrests by law enforcement.” Livingston Parish Public Schools reported that it had no records of referrals to law enforcement for the years requested. St. Tammany Parish Public School System said that it had no documents responsive to the SPLC’s request.

At least one school district provided inaccurate data on referrals to law enforcement.

St. Helena Parish Schools reported that there were no referrals to law enforcement during the 2015-16 school year, but reported in the CRDC that 17 students were referred to law enforcement for 2015-16.

Some school districts reported more arrests than referrals, suggesting confusion.

The CRDC defines a referral to law enforcement as “an action by which a student is reported to any law enforcement agency or official, including a school police unit, for an incident that occurs on school grounds, during school-related events, or while taking school transportation, regardless of whether official action is taken. Citations, tickets, court referrals, and school-related arrests are considered referrals to

law enforcement.”

Accordingly, the number of reported school-based arrests should be less than or equal to the number of reported referrals to law enforcement – not greater. In the most recent CRDC survey (2015-16), however, the school districts below reported to the Office for Civil Rights higher numbers of arrests than referrals, which suggests confusion around the terms and inconsistent data reported as a result.

• St. Tammany Parish Public School System

• Bogalusa City Schools

• Washington Parish Public School System

It is difficult to determine the exact number of SROs in schools.

Nationally, only estimates exist of the number of police in schools. During this survey, the SPLC was unable to use the data reported from school districts to determine the number of SROs in their district for the 2017-18 school year for the following reasons:

• Some law enforcement agencies did not respond to any portion of our public records request. The failure to do so rendered the SPLC unable to verify the accuracy of the school districts’ responses.

• The CRDC data on the number of school resource officers in school districts for the 2017-18 school year is not yet available, adding to the difficulty of checking the accuracy of information reported by the school districts.

Also, while the Every Student Succeeds Act requires the annual reporting of school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement, it does not require school districts to report the number of school resource officers within their district.

Recommendations

As school districts and lawmakers consider implementing or expanding school-based policing programs, it is imperative that accurate, quality data is collected and reported to meet state and federal obligations. Schools also have an obligation to parents and community members to ensure that their tax dollars are funding effective programs that keep schools safe and promote a positive school climate.

As the SPLC’s findings demonstrate, current data collection practices on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement fall short of school districts’ federal obligations, making it impossible to determine the effectiveness of school policing programs. Lawmakers, the Louisiana Department of Education, and Louisiana school districts and their boards, must consider the following recommendations to improve data collection:

For the Louisiana Legislature

Require the annual collection and public reporting of student discipline data.

• This data should include school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement in the disaggregated form required by federal laws and regulations. The state’s existing laws do not explicitly require the collection and reporting of school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement, unlike states such as Arkansas, Maryland, and Kentucky.

• At a minimum, legislation should require disaggregation of this data by race, national origin, sex, and disability status to ensure that school policing programs are not violating the civil rights of these protected groups.

Require school districts to annually collect the total number of SROs in its schools.

Despite the Office for Civil Rights requiring school districts to report data on the total number of SROs placed in the district – data published in the biennial CRDC Survey – it is difficult to verify its accuracy, as there are no state laws requiring school districts or law enforcement agencies to publicly report SRO data annually.

For the Louisiana Department of Education

Work with school districts on an ongoing basis to ensure data accuracy.

• The department should devote adequate staff resources to ensure the accuracy of school- and district-level data, and implement accountability measures to ensure data integrity, including an emphasis on disaggregating data as required by the Office for Civil Rights.

• The department should provide best practices for data collection by school districts, as other states, such as Maryland, have done.

Publicly report state and district level school data, including data on school-based arrests, referrals to law enforcement and SRO data.

• Data on school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement should be reported publicly, disaggregated as required by the Office for Civil Rights for the Civil Rights Data Collection and under the Every Student Succeeds Act, and in a manner that parents and others can easily understand, as required by the ESSA.

• The department should include state- and district-level data on the total SROs in its school safety report posted on its website. Currently, the department does not publicly report school-based arrest and law enforcement referral data on its website, despite the requirement under the ESSA.

For Louisiana school boards

The district’s annual budget should prioritize the hiring and training of a district-wide data manager as well as ensure adequate data collection software is available.

• Each school district should have a data manager overseeing the accurate collection of school data. This manager would be responsible for reporting data to the Office for Civil Rights for the CRDC Survey and to the Louisiana Department of Education for the ESSA Report Card.

• Each school district should have data software that is regularly updated and maintained for data collection, reporting, and analysis.

For Louisiana school districts

Use the Louisiana Department of Education School Behavior Report form to collect data on when a disciplinary infraction results in an arrest or referral to law enforcement.

The Louisiana school data collection statute requires the completion of the report form (Appendix C) by school personnel to document each disciplinary infraction by a student and the school’s response. The form, which contains codes for school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement, is currently used to inform a student’s parents or guardians, but could be used to collect school-based arrest or referral data. The form also documents the disability status of the student, making it easier to determine the number of students with disabilities arrested or referred to law enforcement.

Collect data on the number of SROs in the district for each school year.

Each district – not each school within the district – should annually document the number of SROs on the district’s school campuses and submit the data to the Louisiana Department of Education.