Introduction

Between 2016 and 2018, Americans witnessed a major upswing in street mobilization by far-right groups, making it one of the most active periods of on-the-ground, extremist activity in decades.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) has documented 125 rallies, marches and protests nationwide, which were organized and attended by far-right extremists, including white nationalists, neo-Nazis, Klansmen, the “alt-right,” and right-wing reactionaries during these three years. There were 74 of these events in 2017 alone, the SPLC found.

Those years represented a high point in the movement’s faith in the political process – a faith that has wavered as right-wing extremists have increasingly lost confidence in President Donald Trump. As a result, they have resorted to more authoritarian means of achieving their political goals. Many have retreated from the streets entirely, joining more clandestine extremist cells that believe America’s multiracial democracy is headed for inevitable collapse. These so-called accelerationists call for violence to speed the process along.

For example, while members of the far-right “boogaloo boys” took to the streets in 2020 during the nationwide protests sparked by the police killing of George Floyd, their aims are fundamentally different from radical right groups that did so during Trump’s candidacy and the early years of his presidency. The boogaloo boys do not plan their own rallies and do not intend to act as an insurgent political force seeking mainstream power.

Instead, they hope to exacerbate larger political tensions and push the country toward a second civil war. For the boogaloo boys and similar groups, taking to the streets is not a return to the far-right politics of protests that the nation previously witnessed, but a shift toward more authoritarian, anti-democratic – and even violent – tendencies within the radical right.

As this report demonstrates, there are two distinct periods of far-right activism within recent years, with the latest period harboring an increased threat of violence.

Before the Trump era, far-right public rallies were infrequent. Members of the radical right favored suit-and-tie conferences and used the internet to spread their message, hoping it would bleed into the mainstream. The rise of Trump, a political figure who relied on much of the same divisive rhetoric the far right has historically used to galvanize its membership transformed the political landscape.

The radical right suddenly felt a connection to mainstream politics and a realistic hope of gaining political power, which drew more adherents – and a wider variety of adherents – to the movement. Unsurprisingly, the movement saw an upswing in rallies and other activism.

These rallies promoted white nationalist conspiracy theories, while some members of the radical right pitched their rallies as a way to address a broad swath of right-wing grievances, concerns over free speech and conspiratorial beliefs that antifa posed an authoritarian threat to the nation. At their core, these rallies were about propaganda. Participants and spectators bonded over a perceived victimhood and claimed they were opposing violent leftists.

White nationalist organizations were also taking to the streets, energized by the activism of the broader political right opposing calls to remove Confederate memorials. More than 360 rallies backing the Confederate battle flag occurred shortly after June 2015 and through the end of that year. It was June 2015 when nine Black people were killed by a white supremacist at a Charleston, South Carolina, church. Photos later surfaced of the gunman with the Confederate battle flag. The eruption of support for the racist symbol and subsequent rallies created a space for hate group members to inject explicit, white racial grievance into the mix of anti-government, pro-Confederate and pro-Trump discourse.

The overall level of activism the radical right was able to sustain between 2016 and 2018 would not have been possible without the ties that extremists forged on social media. Facebook and Twitter, in particular, allowed them to coordinate easily, promote events, spread propaganda and recruit new followers – often anonymously. They built a sense of shared purpose and community online, an indispensable part of why people left their keyboards for the cross streets and parks of Sacramento and Berkeley, California; Portland, Oregon; Charlottesville, Virginia; Washington D.C.; and other cities.

“Basically, it makes me feel part of something bigger than myself and it doesn’t make me feel so alone and so … atomized,” one self-described “red-pilled” man told a HuffPost reporter in 2018 as he stood outside an event organized by Richard Spencer, a white nationalist who came to prominence during Trump’s campaign. “Red-pilling” refers to the adoption of far-right beliefs on race, gender and ethnicity.

While it didn’t cause rallies to cease entirely, the deadly rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, proved to be a turning point in far-right activism. Before the rally, the radical right was, to an unusual degree, able to look past ideological and tactical differences that have historically divided the movement. The unity and networking the radical right had experienced as a result of its public activism resulted in hundreds of people with tiki torches marching through the Virginia college town. The next day, one of those extremists rammed his car through a peaceful group of anti-fascists, killing activist Heather Heyer.

Amid the public backlash and lawsuits, white supremacists largely retreated to the internet, focusing on creating spaces that could radicalize young men. But on-the-ground action didn’t stop. Groups without explicit racist or fascist aims picked up the far right’s propagandistic efforts.

In the spring and summer of 2018, the Proud Boys, an all-male group of far-right reactionaries, took the lead. The group carried out a series of rallies in the Pacific Northwest where members outfitted themselves to go to battle with anti-fascists. But after New York City prosecutors charged 10 members of the Proud Boys with riot and attempted assault connected to an October 2018 fight, they, too, largely pulled back.

The radical right continues to build a movement it believes capable of achieving its revolutionary ends, though its tactics have changed. Rallies no longer hold the strategic value they did in the early days of the Trump era, nor does Trump hold the appeal for a movement disappointed by his inability to fulfill their ethnonationalist or ultra-nationalistic visions.

As a result, the far right has drifted toward more revolutionary ends and taken aim at the state itself. White people, they believe, are facing an apocalyptic threat and need to take action against the “international Jewry sealing the doom of my race,” as an online manifesto tied to the 2019 Poway, California, synagogue shooting suspect put it.

Others in the movement may be prepping for the “Hispanic invasion,” according to another online declaration linked to the accused shooter in the El Paso, Texas, Walmart killings in 2019. In attacking those they consider enemies, members of the far right want to awaken white people to what they see as a campaign of racial erasure – or “white genocide” – being committed against them. Each act of violence committed by the movement is part of a larger movement to destabilize the state and bring about a race war.

As this report shows, the radical right is actively looking to exploit today’s historically polarized political climate – one that has become even more uncertain under the strain of the coronavirus pandemic and protests for racial justice. With the 2020 presidential election fast approaching, the prospect that extremists might resort to political violence is a very real one.

Background

America has a history of sanctioning extrajudicial actions and public displays that reinforce racial segregation, carried out by formal organizations such as the Klan or by ad hoc mobs. Though the form of mobilization has varied, these operations were aimed at bonding participants and showing the strength of their numbers while intimidating communities of color.

Racist groups saw their numbers shrink during the apex of the civil rights movement but experienced a boom during the 1970s as white Americans grew anxious over shifting race and gender relations, increased immigration and growing economic precariousness. Klan membership gives some evidence of the radical right’s growing appeal; historian Kathleen Belew noted it grew from 6,500 in 1975 to 10,000 active members and 75,000 sympathizers by 1979. That year, members of the Invisible Empire of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan attacked marchers from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Decatur, Alabama. Months later, Klansmen and neo-Nazis killed five anti-Klan demonstrators in Greensboro, North Carolina.

While organized white supremacists continued to use violence against Black people and their allies, by the late 1970s they also put the federal government – which had dismantled much of the legal structures upholding segregation – on their list of enemies.

The Zionist Occupation Government, or ZOG, was the true root of their troubles, extremists asserted. The state, as they saw it, was allowing nonwhites to usurp white power with the adoption of policies such as affirmative action. White nationalists went so far as to declare war on the U.S. government, marking what Belew in her book “Bring the War Home” calls a “revolutionary turn” in the early 1980s that helped birth the anti-government militia movement. Tactics shifted from marches and rallies toward assassinations and other acts of targeted violence.

The anti-government movement surged in the early 1990s, buoyed by outrage over the standoff in Ruby Ridge in Idaho and the siege in Waco, Texas. It ballooned to 858 groups the year after the Oklahoma City bombing, according to an SPLC tally.

That 1995 attack was the deadliest outcome of the white power and militia movement’s growth. It also dramatically changed how federal law enforcement approached domestic terrorism, leading to the creation of a task force to address the issue. A series of high-profile arrests and federal and public scrutiny significantly weakened the militia movement, and by 2001 a SPLC count found 158 antigovernment groups still holding on.

As the militia movement dwindled, white supremacists became more tightly focused on building a racist community and subculture. Neo-Confederates and violent racist skinhead groups flourished during the 1990s and early 2000s, driven by battles over the removal of Confederate monuments and the rise of a racist music scene. Festivals such as the skinhead Hammerfest drew nearly 500 people outside Atlanta in 2000, while the neo-Confederate League of the South (LOS) reached a peak of nearly 9,000 members among 96 chapters that year, according to an SPLC report.

Other racist organizing during the Clinton and George W. Bush years took place in conference centers and in pseudo-academic journals. Attendees at racist gatherings such Jared Taylor’s annual American Renaissance meeting masked race science with a layer of academic jargon. Taylor’s closed-door, bourgeois brand of racism aimed to shift policy by mainstreaming race science.

The Obama Years

Barack Obama’s election as America’s first Black president in 2008 was a boon for the radical right. A slew of racial bias incidents accompanied the historic occasion, and conservative media outlets were more than willing to give oxygen to nativist and anti-Muslim conspiracy theories, including the Obama “birther” conspiracy championed by Trump. Conservative pundits and politicians loudly rebuked a 2009 threat assessment from the Department of Homeland Security warning of a looming domestic terrorism threat from white supremacists. The report was retracted, and DHS issued an apology under pressure from the right.

The day after Trump’s 2015 presidential campaign announcement, Dylann Roof, a white supremacist radicalized online, murdered nine Black congregants at their church in Charleston. After South Carolina removed the Confederate flag from its Capitol grounds in response to the crime, pressure mounted to take down the flag and other monuments to the Confederacy from public spaces.

Attempts to eliminate these racist symbols helped fuel a narrative of right-wing victimization and, for the first time in decades, propelled large numbers into the streets. The SPLC documented 364 pro-Confederate rallies from June 20, 2015, to Dec. 15, 2015. A July 2015 gathering in Alamance County, North Carolina, drew an estimated 4,000 people, according to a local news report.

Hate group leaders did not organize the bulk of these rallies, but organizations such as LOS and the Council of Conservative Citizens, which are hate groups, were well-represented at them. They cataloged “pro-Confederate activism” on their websites and asked members to share their ideology with potential converts. League member Eric Meadows wrote on the LOS website that he handed out 400 copies of the group’s print tabloid, The Free Magnolia, at a 2015 pro-Confederate event in Georgia.

Pressure to take down Confederate symbols provided ammunition for conspiratorial fears of “Southern demographic displacement.” But when it came to strengthening the radical right, Trump’s presidential campaign helped in a way nothing else had. He opened up space for white nationalists, allowing them to air their views beyond the symbolic defense of the Confederate flag. With debates over a border wall, immigrants and Muslims animating the campaign, members of the radical right found themselves with new avenues to enter public discourse. They readily borrowed Trump’s rhetoric. A small Klan group held the first notable white nationalist rally of 2016 in Anaheim, California, to denounce, as one participant told the Los Angeles Times, “illegal immigration and Muslims.” Three people were stabbed at the rally, the paper reported.

White nationalists didn’t always need to host events. Trump rallies provided a similar collective experience with an affirmation of beliefs, an acknowledgement of shared animus and the potential for violent encounters with perceived political opponents. After the Council of Conservative Citizens – the group whose website church shooter Roof cited as part of his radicalization – canceled its annual conference in August 2015, the League of the South’s Brad Griffin noted on his blog he would go instead to a Trump rally in Mobile, Alabama.

The Battle of Sacramento

Trump’s campaign events encouraged a combative form of politics, where attendees came together in opposition to protesters, journalists and establishment politicians. From the dais, Trump appeared to sanction violence as a legitimate way to handle political opposition. At one rally he acted out how, if given the chance, he would have punched a protester who tried to storm the stage. At another, he lamented that “nobody wants to hurt each other anymore.”

His rhetoric may have had a measurable impact in the communities where he spoke. A study by political scientists at the University of North Texas and Texas A&M University found that counties that hosted Trump rallies in 2016 saw a 226% rise in reported hate crimes over comparable counties that didn’t hold such events.

Far-right commentators also pointed to confrontational moments outside the events – especially one in San Jose, California, where protesters pelted a Trump supporter with an egg – as evidence that conservatives were under attack.

“As we saw in San Jose, where police looked on with apathy as white people using their right to free speech … were beaten before their eyes,” Matt Heimbach of the Traditionalist Worker Party (TWP) wrote on that group’s website, “it is clear that the established system is not only not on our side – it enables and empowers the so-called ‘radical’ anti-white terrorists.”

By early 2016, Heimbach’s neo-Nazi group was one of the more prominent players on the scene. That June, members held a rally at the California Capitol with the Golden State Skinheads. Citing “brutal assaults” against Trump supporters at California rallies, TWP said the Sacramento event was an attempt to protect the white race. “With our folk on the brink of becoming a disarmed, disengaged, and disenfranchised minority, the time to do something was yesterday!” Heimbach declared on the TWP website.

The Sacramento rally created a playbook that the far right would follow in the next two years. Groups would announce an event in advance on social media, allowing counterprotesters time to mount a response. On the day of such a rally, the right learned that police were sometimes more inclined to observe than interfere. In such an atmosphere it was easy enough for weeks of online posturing to turn into violence.

At the California Capitol, some 30 white supremacists faced off against a much larger group, according to The Sacramento Bee, in what one observer called a “free-for-all.”

“The police really didn’t step in at all,” Cres Vellucci of the National Lawyers Guild told the paper, describing violent clashes between the two sides.

At least 10 people were hurt in the melee, reports said, with TWP and the Golden State Skinheads taking credit online for hospitalizing “six Antifas.” The white nationalists also claimed victory with an abundance of social media videos, pointing to them as proof of leftist violence. The far right found that such images could be used to justify retaliation.

Some members of the radical right recognized the Sacramento rally was meant to be provocative. “This was Matt’s plan,” Mike Peinovich said of Heimbach on “The Daily Shoah” podcast. “He knew he was going to get a reaction. He got it, and it’s now amplified his message.”

Peinovich also laughed off the notion that the alt-right – a term then gaining traction to describe the white nationalist movement – was interested in protecting free speech. “I don’t care if you personally believe in free speech – like when we inaugurate our Reich obviously commies go to the fucking gulag right away,” he told others on the podcast.

But messaging around free speech was advantageous. It allowed the alt-right to appear sympathetic to the public while offering a possible legal mechanism against leftists, universities and municipalities it accused of denying civil rights to its members.

“Right now, we have a legal system in place that can cause these people pain,” Peinovich said on the podcast, “and we have to do it.”

These far-right rallies weren’t so much about taking a political stand as about creating a spectacle. And the Sacramento rally taught the radical right that a lot of people – especially in liberal West Coast cities – were willing to come out in protest using aggressive tactics that could, in turn, aid the right’s propaganda efforts.

‘Triggering the Libs’

The term alt-right became inescapable during the 2016 presidential election. Though the media puzzled over its definition, it was simply a distinct moment within the long history of white nationalism. The rebranding was strategic. Hate groups “played on the media’s fascination with novelty to give their ideas mass exposure,” researchers wrote in Data & Society in 2017.

A cadre of influential propagandists emerged, including Andrew Anglin of the Daily Stormer, Peinovich of The Right Stuff, Richard Spencer of the National Policy Institute, and husband-and-wife team Lana Lokteff and Henrik Palmgren of Red Ice Radio. The goal for many associated with the alt-right was to create content aimed at radicalizing internet users, but trolling was another movement-building strategy. “Triggering the libs” united disparate parts of the far right as it tried to provoke responses from “social justice warriors” and the mainstream media.

One example was the “He Will Not Divide Us” installation in New York that actor Shia LaBeouf collaborated on with other artists to counter Trump’s rhetoric. In front of a camera placed on an outer wall of the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, participants were instructed to repeat the words: “He will not divide us.” The art project drew the ire of 4chan’s /pol/ board, an associated Discord server known as Outer Heaven, and Reddit’s /r/The Donald forum.

Before long people from all corners of far-right internet culture appeared at the installation, leading museum security to erect barriers to control the crowds. The museum said the installation “had become a flashpoint for violence,” marked by arrests (including LaBeouf’s), and shut down the project because it created an “ongoing public safety hazard.” “He Will Not Divide Us” became a roving exhibit for some months, but the trolls on 4chan persisted. When LaBeouf livestreamed a flag bearing the project’s name from an unnamed location to give his artwork new life, internet sleuths used flight patterns to determine where it was located. The flag may now be hanging in the home of a troll who reportedly made off with it in Tennessee.

The episode undoubtedly provided entertainment to those watching it play out online, but it also helped forge social bonds. A member of the New York City Daily Stormer Book Club told a journalist with the pseudonym “Jay Firestone” that, as a result of LaBeouf’s project, the alt-right scene in the city became “completely cross-pollinated.”

The alt-right was also converging on other fronts, dedicating itself not just to mocking enemies but instilling fear. In December 2016, after Anglin, Peinovich and Spencer appeared together on a podcast episode dubbed “The First Triumvirate” to unify their fan base, Anglin went to work on Spencer’s behalf. A Jewish real estate agent in Montana who had been in contact with Spencer’s mother found herself the victim of a troll campaign that Anglin launched on the Daily Stormer. At one point, Anglin threatened to bus armed skinheads to Whitefish, Montana, indicating the movement’s understanding of how marches could erode a community’s sense of security.

Alt-right rallies became a form of “mass triggering.” When it came to creating such spectacle, Milo Yiannopoulos, whom The New Yorker aptly described as a “right-wing professional irritant,” was unmatched. During his “Dangerous Faggot” tour (a name designed to make light of his sexuality and provide a cover for his bigotry), Yiannopoulos consistently targeted vulnerable people, including trans students and immigrants, to whip up his political opponents. He mocked a trans student at a December 2016 appearance at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, revealing her name and photo to the audience. That same month, he called a West Virginia University instructor a “fat faggot.” He frequently denigrated Muslims and made disparaging remarks about feminism, which he described as “a bitter, nasty, ugly, man-hating empty horror show.”

Nevertheless, much of the alt-right considered Yiannopoulos a nuisance. On “The Daily Shoah” podcast, Spencer, along with Peinovich and his co-hosts, devoted a segment to putting down Yiannopoulos, accusing him and the rest of the “alt-lite” of lacking core political tenets except an unwavering enmity toward “SJWs,” or “social justice warriors.”

Despite such ridicule, Yiannopoulos was one of the alt-right’s greatest allies because of his ability to deliver its ideas to his audience when he was an editor at Breitbart News. Emails uncovered by BuzzFeed in October 2017 revealed that Yiannopoulos had shaped a long-form explainer about the alt-right for Breitbart with the editorial input of white nationalists – including Andrew “weev” Auernheimer of the Daily Stormer and American Renaissance editor Devin Saucier. Journalists from mainstream publications had cited the piece when describing the racist movement, ultimately allowing members of the alt-right to shape their own public image.

As he was helping spread racist messages to a broader public, Yiannopoulos was also siphoning young men from the conservative and libertarian movements into the radical right. Yiannopoulos guided innumerable young men toward extreme material, leading many to embrace overt racism. Research conducted by the SPLC in 2018 found that more than 12% of users who posted on Peinovich’s forum, The Right Stuff, about their radicalization cited Yiannopoulos as an influence.

But perhaps Yiannopoulos’ greatest service to the radical right was the parade of angry protesters his tour produced. The tour coincided with the early days of the Trump presidency, when political tensions were high, and the right was thirsty for content that presented any opposition as coordinated and threatening. After the inauguration, where police arrested 200-plus anti-Trump protesters and Spencer was punched in the face on camera, Griffin of the LOS concluded the left “now wants to cross the final line into civil war.”

Violence erupted as well on the opposite coast on Inauguration Day when a counterprotester was wounded outside where Yiannopoulos was speaking at the University of Washington in Seattle. Elizabeth Hokoana was charged with first-degree assault in the shooting of a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, while her husband, Marc, was charged with third-degree assault over firing pepper spray into the crowd.

A judge declared a mistrial in the Hokoanas’ trial in August 2019 after jurors deadlocked along what the foreman described as ideological and political lines, reports said, and prosecutors ultimately decided not to retry the couple.

The University of Washington College Republicans, which had sponsored the Yiannopoulos event, reportedly blamed the shooting on “Antifa, Anarchists, [and] violent political agitators.” He warned on Facebook: “If you keep prodding the right, you may be unpleasantly surprised what the outcome will be.”

The shooting didn’t keep Yiannopoulos from forging ahead with his college tour. Less than two weeks later, his planned speech at the University of California, Berkeley, kicked off a series of violent confrontations that lasted throughout the spring and summer of 2017. Citing a Breitbart article that Yiannopoulos was joining with anti-immigrant activist David Horowitz to “take down the growing phenomenon of ‘sanctuary campuses’ that shelter illegal immigrants,” the Berkeley Office of Student Affairs warned that the campus speaker might out undocumented students.

Ultimately, Yiannopoulos didn’t speak at Berkeley. The university canceled the event due to public safety concerns after protests became violent.

If Yiannopoulos needed any more proof that his flame-throwing rhetoric could create the kind of spectacle the far-right thrived on, he got it in the form of a tweet from Trump. “If U.C. Berkeley does not allow free speech and practices violence on innocent people with a different point of view – NO FEDERAL FUNDS?” the president tweeted.

The Right Begins to Unite

While Yiannopoulos racked up huge security bills and headaches for universities, he inspired envy in others on the far right who craved the kind of controversy that seemed to follow him. In late 2016, Spencer announced his own college tour. He had spoken at individual events at Vanderbilt University in 2010 and at Providence College in 2011 on invitation from local chapters of Youth for Western Civilization, led then by white nationalist Kevin DeAnna, but his 2016 tour now drew from Yiannopoulos’ playbook while introducing students to what Spencer called “real” alt-right ideas.

Spencer’s “Danger Zone” tour took advantage of some open-ended policies that allowed nonstudents to invite speakers to colleges, setting off legal battles as universities attempted to stop him from bringing protests and chaos to their campuses. When Auburn University attempted to cancel an appearance by Spencer, it reportedly ended up paying $29,000 in legal fees to a man who had booked a venue for the speech.

Spencer’s tour helped to build new levels of coordination and collaboration among the radical right. He surrounded himself with a sprawling network of activists who provided legal representation, built media and messaging plans, coordinated with campus police and arranged security for himself and other members of his cadre. Members of LOS, the Traditionalist Worker Party and circles surrounding The Right Stuff were involved in Spencer’s campus tour, creating the sense that the far right was experiencing unprecedented levels of unity.

Most communication took place online and helped to birth a number of intel and planning groups on platforms such as Facebook that, through subsequent events, eventually grew into a dense organizational network.

One example was the online space that Griffin, the public relations chief for LOS, created to prepare for a 2017 rally aimed at stopping the city of New Orleans from removing a monument to Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. The Facebook event page “Anti-Antifa Action NOLA working group” and a private group called “The Proud Goys” (a title clearly aimed at mocking the alt-lite group Griffin considered insufficiently extreme) acted as a big-tent organizing hub for white nationalists, neo-Confederates, neo-Nazis, alt-right trolls and militia members who found common cause over the defense of Confederate monuments. Members included “Keith Swing,” vice commander of Vanguard America’s Louisiana chapter; William Finck, a former jail guard and author of the Christian Identity website Christogenea; Justin Burton, who claimed Oath Keepers and Three Percenter militia affiliations on his Facebook page; Tyler Tenbrink of a Three Percenter group known as the Texas Ghost Squad; and Shaun Winkler of the LOS, Aryan Nations and the International Keystone Knights of the KKK.

This forum provided a place for possible attendees to get each other riled up. “We are going to have to understand and be willing to play dirtier and 1000xs crueler than these little 20-year-old gay, fag hags, Jew Antifa bitches could have ever anticipated from a people that has been walked on for close to 160 or even more years!” Adrian Cox Ingram of the Florida League of the South posted. When it appeared that antifa might not show up in the numbers expected, one group member seemed less than disappointed: “I like hitting orcs more than I do commies, I am cool with that.” In this context, “orcs” is used as a pejorative for Black people.

On the day of the rally some 150 protesters, many waving Confederate battle flags and LOS “Southern nationalist” flags, surrounded the monument. “There’s going to be antifa blood on this pole,” one helmeted man with a flagpole told a local reporter. An estimated 500 people who supported the statue’s removal surrounded the monument and its defenders.

Police barricades, fortunately, prevented any violence, and Lee’s statue eventually came down. But the radical right, more unified than it had been in decades, marched forward with renewed confidence.

Viral Violence as a Recruitment Tool

Tensions exploded during the 2017 “Summer of Hate” – as the Daily Stormer’s Anglin dubbed it – especially on the West Coast. Some members of the radical right realized that, even while claiming to be victims of liberal overreach, they could capitalize on their own violent acts. Video of a dramatic punch could go viral, making heroes out of the movement’s street warriors and recruiting people to the cause.

One such viral act of violence came at a pro-Trump rally in Berkeley on March 4, 2017, in Berkeley when a commercial diver named Kyle Chapman bashed a counterprotester over the head with a wooden rod. Far-right admirers quickly nicknamed Chapman “Based Stickman,” endlessly sharing images of him charging, clad in homemade armor with stick held aloft.

Chapman told The New York Times he was first drawn to the movement after seeing video of a Trump supporter being pepper-sprayed when Yiannopoulos tried to speak at Berkeley. Chapman’s story was the same for many who would join the rallies: They saw the events on Facebook or other platforms and felt compelled to get involved. The far right had built enough momentum that by the April 15, 2017, “Patriots Day” rally – “The Second Battle of Berkeley” – about 200 people showed up to stand against the “SocJus [Social Justice] World Order,” as one alt-right online chronicler put it.

Violence was the main promotional vehicle for the rally. “We hope the Antifa shows up with a lot of sticks and mace. That way we can legally beat the hell out of them,” a Los Angeles Proud Boy named Sabo said in a Periscope video, as reported by Berkeleyside. The news site noted that many others echoed his message. “We need to do whatever it takes to make sure this doesn’t end up like that Milo event.… Even if it means killing any rioters dressed in black with lethal force,” a person with the handle @antifa_suckass tweeted. Members of the white nationalist street-fighting group Rise Above Movement (RAM) celebrated footage of their members attacking counterprotesters at a “Make America Great Again” rally in Huntington Beach, California, in the runup to the Berkeley rally.

Berkeley turned out to be one of the most chaotic events of the summer of 2017. RAM members, with their faces concealed by bandanas and skull masks, instigated some of the first clashes. According to a criminal complaint filed by the FBI, RAM members later bragged on Twitter that they were “the first guys to jump over the barrier and engage,” which they said had “a huge impact.” They allegedly hunted down and assaulted counterprotesters who were attempting to leave the park where the rally began. Two RAM members broke their hands at the rally, according to an indictment. Prosecutors noted that rather than discouraging future altercations, another RAM member suggested adjusting their training to emphasize using “palm strikes” to avoid similar injuries.

The “Second Battle of Berkeley” lived up to its name. Hundreds turned out in the streets, where the sounds of M-80 firecrackers and pepper spray intermittently filled the air. The violence became at a certain point “ritualized and predictable,” according to journalist Shane Bauer in Mother Jones. Berkeley was “a total Aryan victory,” RAM member Michael Paul Miselis later declared in a text message.

As video of the fighting made its way online, no moment captured the heart of the right-wing internet more than when Nathan Damigo, the founder of Identity Evropa, punched a dreadlocked woman in the face. The “falcon punch” video reportedly racked up more than 663,000 views in the two days that followed the rally. Damigo was a “true hero,” according to the Daily Stormer. The punch brought him to the attention of mainstream media, too (including an interview with The New York Times), helping to elevate Identity Evropa’s profile.

Members of the so-called alt-lite, who claimed not to hold the racist views of the alt-right, capitalized on the events in Berkeley, exhibiting little concern about the extremists who wanted to share the streets with them.

One of those was Gavin McInnes, a founder of Vice Media. In 2008, after severing ties with the outlet and moving onto right-wing platforms such as Compound Media, he launched a men’s group of “Western chauvinists” called the Proud Boys. McInnes had long trafficked in white nationalist tropes and been friendly with members of the movement, though he was careful to address race with a sense of ironic detachment. He distanced himself from the first Berkeley rally in March, but, according to the Berkeleyside news site, offered support for the second event after seeing how it had launched the celebrity of minor right-wing figures. The day after the Berkeley rally, McInnes said he didn’t feel like it was “just a little, minor battle that was won in Berkeley. This was a tectonic shift.”

Berkeley did mark a change: The right found that violence drove recruitment and that some law enforcement agencies intervened little in what became open-air forums of radicalization. As the summer of 2017 moved forward, members of the right made every effort to toe up against their enemies as often and publicly as possible.

‘Unite the Right’ and the ‘Optics Debate’

“Unite the Right” in August 2017 was the high-water mark of far-right rallies in terms of attendance, media attention and violence during the period covered by this report.

Like its forerunners, the Charlottesville rally was organized almost entirely online, predominantly on Facebook and Discord. It built on the networks that had been developing through interactions over months of radical right rallies while also helping to foster new relationships among individuals and far-right extremist groups.

For instance, in the “Charlottesville 2.0” Discord server – named so because the first torchlit rally in Charlottesville had been held May 13 – user HueTheHand noted that he first heard about Unite the Right while providing “security” at a June 25 “Rally for Free Speech” at the Lincoln Memorial. The events in Berkeley inspired 19-year-old Baltimore resident Colton Merwin to host the Washington gathering, which featured alt-right figures such as Spencer and Christopher Cantwell. HueTheHand (whom anti-fascists identified as Kevin Cottle) first posted on the Charlottesville 2.0 Discord server four days after Merwin’s event. “[M]e and my guys that pulled security for the DC rally are coming down for this” from Rhode Island, he posted and then, in a channel dedicated to coordinating carpools, invited others to join them.

For more than two months, HueTheHand discussed what tactical gear and clothing to wear to the rally and chatted about security concerns on the Charlottesville 2.0 server. He also explored the TWP during that time. In June 2017, he posted that other attendees at the Washington rally told him to look into TWP. By that August, he was attending the “TWP cabin after party” following Unite the Right.

In channels such as #vt_nh_me, #midwest_region, #georgia, #carolinas, #california_pacific_nw and #beltway_bigots, members such as HueTheHand encouraged each other to come out to far-right events, made racist jokes and planned for Unite the Right.

After months of coordination, upward of 500 alt-right members descended on Charlottesville, bringing the violence that would lead to the death of antiracist activist Heather Heyer.

In the aftermath of the deadly rally, Trump offered notoriously ambiguous remarks, insisting there were “very fine people on both sides.” But the response from anti-racist communities was swift and unequivocal. A “free speech” rally in Boston a week after Charlottesville brought out an estimated 40,000 counterprotesters against a group of right-wingers so small it reportedly fit within the bandstand at Boston Common.

Facing immense public scrutiny, the alt-right entered into what came to be known as the “optics debate.” The question was whether the movement would continue to rally in public events to demonstrate its strength or whether it would be better served by retreating to the internet and focusing on radicalizing propaganda.

Spencer still saw public activism as a benefit to the movement, trying to make left-wingers, university professors and administrators look weak by forcing them to allow an ethnonationalist to speak on their campuses. As Spencer’s Radix Journal put it in his college tour’s original announcement, his presence would “make the SJWs cry … and rustle the jimmies of the campus, if not the world.”

Cameron Padgett, a self-professed identitarian—a euphemism for white nationalism popular with contemporary groups aimed at radicalizing European youths— who applied for the permit for Spencer’s Auburn speech, also obtained a permit for Spencer’s first speech after Charlottesville. Preemptively dubbed “Hurricane Spencer,” the Oct. 19, 2017, event at the University of Florida featured a heavy police presence in anticipation of another near-riot.

The speech went disastrously, with an auditorium of counterprotesters shouting Spencer, Peinovich and Padgett off the stage. Three men from Texas, brothers William and Colton Fears and Tyler Tenbrink, were arrested shortly after the event.

The arrests were sparked by Tenbrink firing a gun into counterprotesters. Colton Fears was sentenced to five years in prison for accessory after the fact to attempted first-degree murder, and Tenbrink got 15 years for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon and possession of a firearm by a felon. Florida prosecutors dropped attempted murder charges against William Fears.

By March 2018, when the TWP and Patriot Front accompanied Spencer to Michigan State University, it was clear the landscape had shifted since Charlottesville. The alt-right was skittish, with Spencer’s supporters reduced to handing out free tickets to his speech in a Macy’s parking lot. The optics failed to improve from there. Students and anti-fascists met the white supremacists and refused to let them enter the agricultural pavilion where Spencer was set to speak. Fights broke out. In the end, police reportedly arrested 25 people – including Greg Conte, operations director for Spencer’s National Policy Institute – and only a few dozen made it to Spencer’s speech.

Members of the movement now choosing to eschew street activism mocked the display: “Watching a bunch of ‘Alt-Right’ fat guys in costumes get shouted down in the street and laughed at … hurts the morale of our own guys,” Anglin, the Daily Storm operator, wrote on Gab, and “takes away from things that we’ve been doing successfully in the propaganda sphere.”

Spencer seemed to agree, announcing in the aftermath of the Michigan event he was ending the college tour to make a “course correction.” “Antifa is winning,” he conceded to The Washington Post.

Public activism began to fall out of favor following the Michigan State debacle, and the groups that came to prominence were the ones that displayed a near-obsession with aesthetics and workshopped talking points (sometimes derisively referred to as “optics cucks” by others in the movement).

Identity Evropa and Patriot Front exemplified this turn. Identity Evropa leader Damigo, who had helped plan the Charlottesville rally, stepped down in its aftermath. Thomas Rousseau, who attended Charlottesville as a member of Vanguard America, broke away from that group and formed Patriot Front. Both white nationalist groups decided they would no longer attend big-tent events and instead held only unannounced “flash demonstrations,” where they carried banners bearing their logos and chanted nativist slogans.

Passing the Torch

After Charlottesville, white nationalists made what alt-right podcaster Douglass Mackey, aka “Ricky Vaughn,” called a “tactical retreat back to the internet.” “Maybe you’re going to have to abandon the alt-right as something that’s in real life,” he said on a March 2018 episode of the podcast “Strike and Mike.” “Maybe it’s going to be an online counterculture, and you’re going to go into the street as something else.”

As the alt-right vacated the streets, the Proud Boys stepped in. Though some members were present at Unite the Right, the group’s founder, McInnes, publicly disavowed the event beforehand, much as he distanced himself from the first Battle of Berkeley. That meant the Proud Boys could move in – almost always under the banner of “free speech” – without the same level of scrutiny as neo-Nazis and white nationalists.

The Proud Boys furthered the mission of the alt-right, whatever their protestations. While being deeply misogynistic and anti-Muslim, the group focused its message predominantly on opposition to the left – a wide swath of the political spectrum reduced to a cartoonishly violent menace that could only be met by force. Their street battles against anti-fascists, which peaked in the summer of 2018, perpetuated the far right’s narrative that the left was unhinged and hellbent on imposing political correctness on the masses.

The Proud Boys were most active in the Pacific Northwest, particularly Portland. The Oregon city had two things making it a tinderbox: a robust anti-fascist movement ready to meet the Proud Boys in the streets and a right-wing leader named Joey Gibson willing to lead an endless string of rallies. Gibson was not a Proud Boy, but his Trump-supporting group, Patriot Prayer, consistently partnered with the so-called Western chauvinists.

The summer of 2018 was marked by a series of violent rallies, several of which descended into riots. Nothing helped draw people like the chance to fight in the streets with anti-fascists, and no moment epitomized the allure of violence better than a knockout punch delivered by Ethan Nordean that June at a Portland rally. Right-wingers around the internet celebrated footage of the Proud Boy knocking an anti-fascist protester unconscious. “Seeing that soy boy antifa scum get knocked the fuck out has been the highlight of my year. [I’ve] watched it over and over,” one Facebook user wrote.

But the violence caught up with the Proud Boys. In October 2018, after McInnes gave a speech in Manhattan commemorating the 1960 assassination of a Japanese socialist leader (complete with a re-enactment), riled members of the Proud Boys instigated a fight near the venue. Ten members of the group faced charges related to the fight.

The charges had a chilling effect on the group. It was swiftly removed from a number of social media platforms, including Facebook, which had served as its primary organizational hub. McInnes disassociated himself from the group he founded because, as he said in a YouTube video, it would “show jurors that they are not dealing with a gang and there is no head of operations.” The stream of rallies came to an abrupt halt.

The Rise of White Supremacist Killings

By late 2018, organized and planned far-right rallies had dramatically declined. But the far right was making its presence known in other ways. While public demonstrations ebbed, far-right attacks have become deadlier during the Trump era.

Between 2014 and 2018, men influenced by the alt-right in the United States and Canada killed 81 people, according to numbers tabulated by the SPLC. At least 40 of those killings happened in 2018. Thirteen were in October alone, when two Black people were gunned down in a Kentucky grocery store, followed by the massacre of 11 worshippers at a Pittsburgh synagogue.

In 2019, after a white supremacist was accused of killing 51 people in an attack on New Zealand Muslims, a man in Poway, California, attempted to emulate that attack. His rifle apparently jammed after he entered the Chabad of Poway synagogue on the final day of Passover, but one person was killed and three others injured. An online manifesto tied to the suspect took credit for setting fire to the Islamic Center of Escondido, California, a month earlier. Then in August, a man entered an El Paso Walmart and killed 22 people. An online manifesto linked to that suspect claimed a “Hispanic invasion” was threatening Texas.

More violence was planned or attempted. A Missouri man, Taylor Wilson, was sentenced to 14 years in prison on a terrorism charge after boarding a secure area of an Amtrak train armed with a handgun. Law enforcement said it foiled a plot by Coast Guard Lt. Christopher Hasson, a self-described white supremacist, to kill Democratic politicians and media figures. Hasson pleaded guilty to federal gun and drug charges. Cesar Sayoc pleaded guilty to mailing pipe bombs (which turned out to be duds) to more than a dozen Trump critics and was sentenced to 20 years in prison. A man pleaded guilty to threatening to kill U.S. Rep. Ilhan Omar, who is a Muslim. In less than three weeks following the El Paso shootings, CNN reported that police arrested more than two dozen people accused of threatening to commit mass shootings.

Against the backdrop of this surge of terror, the far right has largely turned away from public rallies, once a sign of its perceived connection to mainstream politics. These rallies demonstrated the hope the movement could have an impact on the halls of power. Trump was there after all, and members of the radical right saw him as a political savior, or at least assurance their moment had arrived.

But the world of 2016 looks very different from that of 2020. Hate groups, by and large, no longer stand by Trump because they don’t believe he stands by them. Spencer declared the Trump moment over in November 2018, tweeting that the administration “differed little from what we could have expected from Jeb [Bush] or Marco [Rubio].” Griffin of LOS expressed his view in Occidental Dissent, “I started out 2017 deeply skeptical of the incoming Trump administration. I predicted ‘we are about to enter the gates of this false paradise.’ By 2018, I was convinced that subsequent events had proven that my assessment was correct.”

The overwhelming emotion among white supremacists now is rage. Many of these white supremacists feel cheated by a president whom they see as failing to fulfill his most authoritarian promises. They face intense scrutiny and resistance when they try to organize in the streets and find themselves being deplatformed from online spaces that initially helped them amplify their message. In the minds of many on the far right, these things amount to proof of a global conspiracy hellbent on white genocide.

As a result of their frustration, some members of the far right have decided to take matters into their own hands. Much of the movement has devoted itself to spreading propaganda-promoting violence, whether it’s footage from the Christchurch, New Zealand, massacre or memes celebrating killers.

The men accused of committing these acts are markedly younger than white supremacist killers who came before them. A study the SPLC conducted of domestic terrorist attacks between April 2009 and early February 2015 – the overwhelming majority of which were committed by one or two people – found that roughly 66% of offenders were over the age of 29. “This suggests,” the report noted, “that perpetrators spend many years on the radical right, absorbing extremist ideology, before finally acting out violently.”

Comparatively, in a report examining killers who were influenced by the alt-right between 2014 and early 2018, the SPLC found that the average age among perpetrators was 26. The internet was clearly a means of communication and radicalization during the period of the earlier study, but it has since come to play an even more crucial role. Research suggests that as the speed at which users can consume information and build networks online accelerates, the period of time for radicalization also shrinks.

Among the most extreme part of the movement, suspects in recent deadly attacks are deemed worthy of canonization. Robert Bowers, accused of killing 11 at the Pittsburgh synagogue, and John Earnest, charged in the deadly Poway synagogue shooting, are now “Saint Bowers” and “Saint Earnest.” “Hail the new saint. I’m really excited to see that you know one is leading to another. The dominoes are in fact falling,” one of the hosts of a podcast called “The Gas Station” said in the aftermath of the Poway attack.

“The gaps between these shootings is growing smaller and smaller each time,” a co-host called Vic Mackey said, adding that “things are heating up, and there’s no putting the cat back in the bag. There’s just too many motivated, angry righteous white men out there who are just reaching the ends of their ropes.”

As the show neared its end, a host by the name of Sarin predicted a future of increasing violence: “I have the feeling that it’s going to continue exponentially and grow and grow, and I can only hope that it does and get this thing really started.”

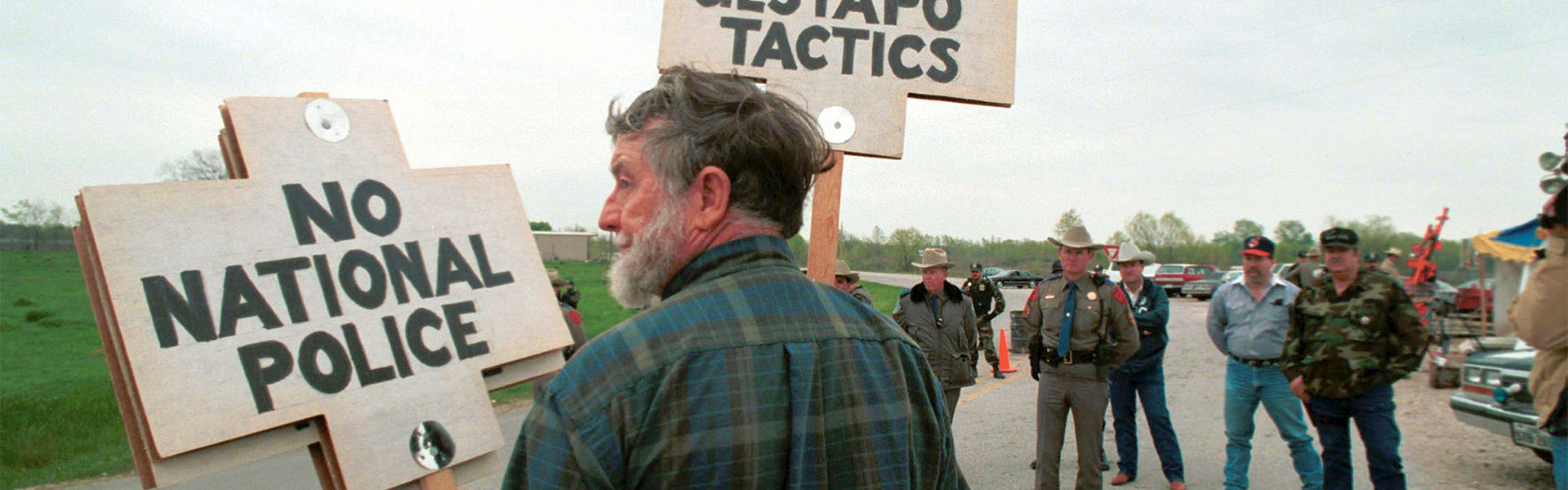

Lead Photo by NurPhoto/Getty Images