James A. Young made history in 2009, becoming the first black mayor of Philadelphia, Mississippi.

It was a milestone in a county with a long conservative history — the place where Ronald Reagan made his famous “states rights” speech at the Neshoba County Fair in 1980, seen as a coded appeal to racists in the South as he sought the presidency.

While the town of 7,400 and surrounding Neshoba County has a long and mixed history, it is hoping the death of a prime mover in an ugly piece of it will allow it to learn and move on from a legacy of hate.

“That stigma is a call for serious change,” Young said.

Like much of the South, Neshoba County has a long way to go.

Freedom Summer killings

Young, 62, recalls his father in the living room of their home in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in the summer of 1964, waiting with a gun in case the Ku Klux Klan came through the front door.

There was “fear, tension, evil in the air,” Young said 54 years later.

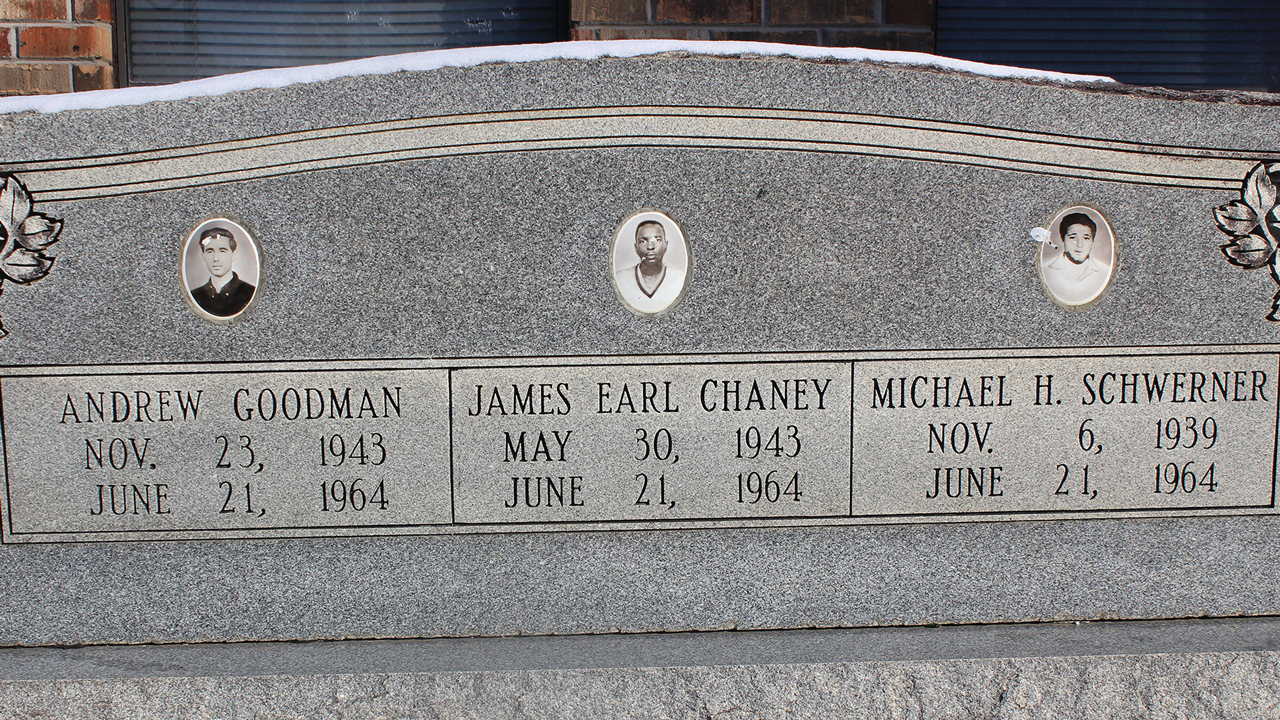

A Ku Klux Klansman, Edgar Ray Killen, led a brigade of fellow racists and local law enforcement in pursuit of three civil rights workers: 21-year-old James Chaney of Meridian, Mississippi, 20-year-old Andrew Goodman and 24-year-old Michael “Mickey” Schwerner, both of New York.

The three were working as part of “Freedom Summer,” an effort by civil rights activists to register as many black voters in the deep South as possible.

Killen’s mob caught up with the three June 21, 1964 after local deputies released them from the county jail. After tailing them down a dark, rural Mississippi State Highway 19, Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were stopped, taken a quarter mile up a rural road then shot and killed, not far from Killen’s home.

Their car was burned and their bodies were buried in an earthen dam, where the FBI found them 44 days later.

Young, who was eight years old then, remembers it as a rough time.

“It triggered almost a helpless feeling,” Young said. “It was almost as if, once again, evil had won.”

State officials refused to prosecute anyone in relation to the crime. The federal government stepped in and charged 18 people with conspiring to deprive Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner of their civil rights.

Seven men were convicted, none serving more than six years in prison.

Jurors deadlocked on charges against Killen, a local minister and sawmill owner and E.G. Barnett, a candidate for sheriff. They weren’t retried on federal charges.

The killings were memorialized in the 1988 movie Mississippi Burning which took its name from the FBI code name for the probe into the slayings “MIBURN.”

A year later, in 1989, on the 25th anniversary of the murders, the U.S. Congress passed a non-binding resolution honoring the three men; U.S. Senator Trent Lott and the rest of the Mississippi delegation refused to vote for it.

After a push of publicity and fresh investigation, in January 2005, the state indicted Killen on three counts of murder, marking the first time Mississippi officials had taken action in the case.

A jury returned guilty verdicts on a charge of manslaughter 41 years to the day after the men were killed, sending Killen to prison for 60 years.

Killen died January 12, 2018 at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at the age of 92. Funeral arrangements for him were not made public.

Going forward

Young hopes Killen’s death closes a chapter for the town and Neshoba County.

“A legacy of hatred and prejudice has died,” Young told the Southern Poverty Law Center. “It kind of puts an end to that era … in Philadelphia and the South.”

While the era may have ended, the legacy of the killings — and the attitude that brought them about — still remain in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and the country as a whole.

Around the corner from Young’s office on Main Street stands the Neshoba County Courthouse and a large monument of a Confederate soldier on the lookout. The statue is a memorial to all from Neshoba County who fought for the South in the Civil War.

Scattered around town and the county are smaller, less noticeable markers to Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner, as well as others who took part in “Freedom Summer” mixed into neighborhoods where both American and Confederate flags fly in front of houses.

The local tourist center keeps maps on hand for a self-guided “African-American Heritage Driving Tour.”

“Not many,” said Tim Moore, a local tourism official when asked how many people seek out the markers. “It’s not many at all.”

At Mt. Nebo Missionary Baptist Church on the west side of town, a stone marker features pictures of the three men along with their dates of birth and death. Go out the state highway and there’s a state-posted marker where the men were killed that’s easy to miss.

It is an ugly part of history that Philadelphia sort of embraces, but hopes others learn from.

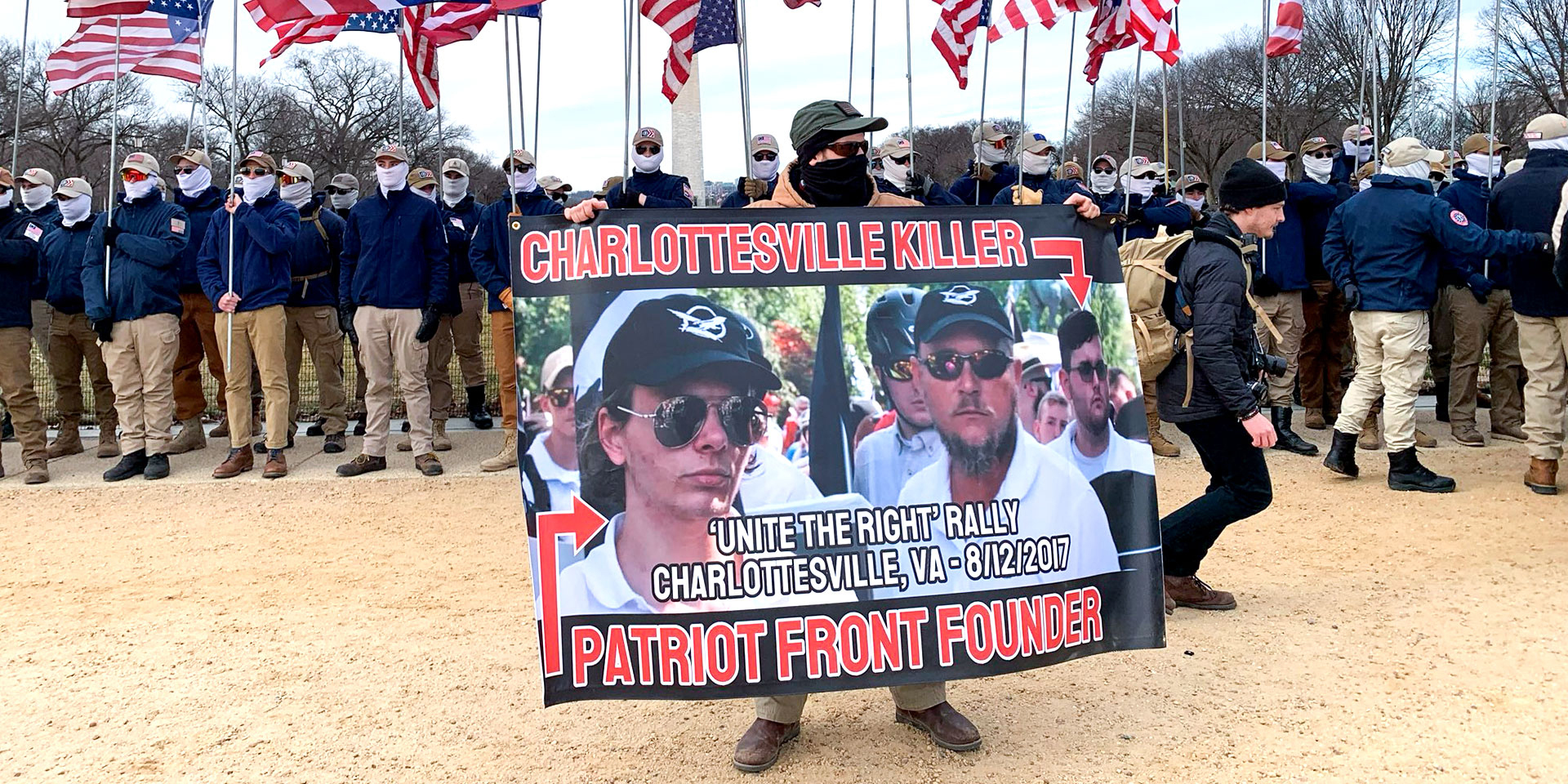

Given the current political climate, with white supremacists, neo-Nazis and white nationalists feeling emboldened in the wake of President Donald Trump’s time in office, Young sees lessons to be learned from the local history.

“Violence is not the way to go,” Young said.

Others with ties to the deaths of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner are hoping for the same thing.

Angela Mccoy-Lewis, the daughter Chaney never got a chance to meet, hopes that, in death, Killen can find peace with her father and others like him.

“A great joy for me would be for me, my dad and Edgar Ray to embrace each other in heaven,” Mccoy-Lewis wrote on Facebook. “I look forward to the day that I will meet my dad. I pray for the Killen family. Spread love.”

David Goodman, the younger brother of Andrew Goodman, lamented the fact that several of the killers “got off scot-free” and that, despite Killen’s conviction, the case “is justice unresolved.”

“The fundamental problem of systemic racism that led to their deaths continues to resurface in America today, most recently in Charlottesville, VA, and Charleston, SC,” David Goodman said in a statement. “We must do better. One thing I am certain of is that my brother Andrew’s story will not die with Edgar Ray Killen. It will continue to serve as a painful reminder of how far we have come and how far we still have to go.”

It’s a sentiment Young, now in his third term in office, agrees with.

“You just want to be a soul that protects life and the dignity of life,” Young said. “We’ve got a lot of work to do on that. You see the rhetoric these days.”