President Donald Trump’s administration is packed with personnel from the ranks of the hard right who use harmful ideologies as a foundation for current policies.

The criticism of many appointees has focused on their white nationalist and overtly bigoted views. One ideologue returning to the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) has faced less scrutiny from the media, however, despite her role in the antigovernment movement and advocacy for county supremacy, a foundational belief of the movement.

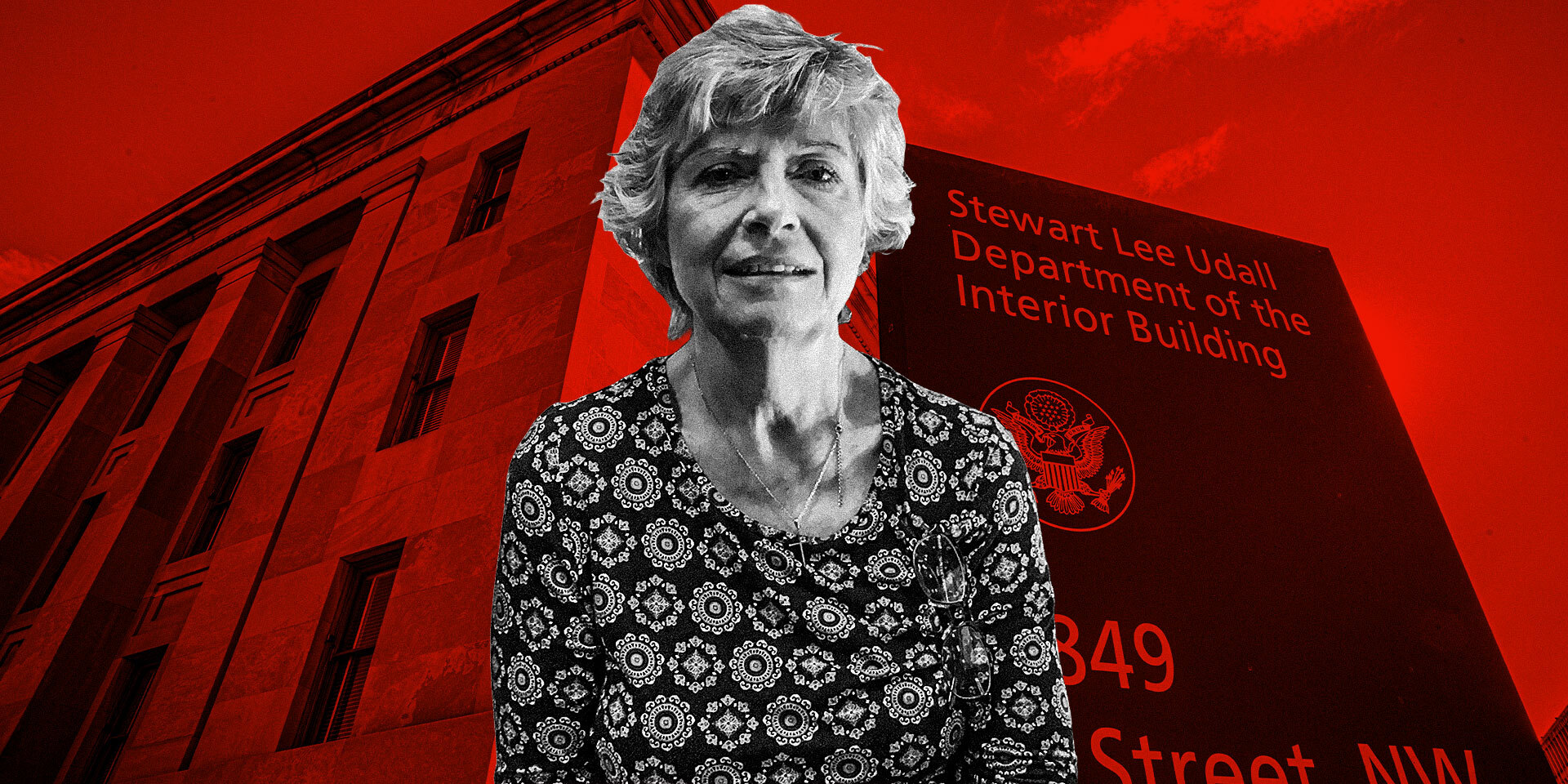

In March, Wyoming attorney Karen Budd-Falen accepted an offer from the current administration to return to the agency as the DOI’s associate deputy secretary. During Trump’s first administration, she served as the agency’s deputy solicitor for wildlife and parks. Her return to the DOI places one of the most notorious promoters of county supremacy in the upper echelons of leadership at the agency managing more than 500 million acres of public lands.

County supremacy maintains that all political power should rest at the county level. It also serves as the ideological bridge that brings together the antigovernment and anti-environmental movements. Since the 1990s, Budd-Falen has made her reputation and career from working at that intersection. She’s told county governments that if they adopt their own ordinances and resource plans based on her ideas, they can demand equal footing with the federal government. According to some reports, upward of 200 counties throughout the West adopted these county supremacy ideas as policy during the 1990s.

After fighting with federal land agencies and partnering with antigovernment extremists for decades, Budd-Falen now assumes the No. 3 position in the DOI. She now helps set the tone for an agency she has sued frequently over the years, including pursuing racketeering charges against employees of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), a part of the DOI.

After decades working at the nexus of the antigovernment and anti-environmental movements, proposing illegitimate legal theories that routinely lose in courts, and ratcheting up anger and targeting federal land managers, Budd-Falen now has the power of a federal agency behind her.

“When you side with armed militia groups and support anti-public land zealots, you are not qualified [to lead the BLM],” Western Values Project’s Chris Saeger said when Budd-Falen received her DOI position during the first Trump administration.

The Western Watersheds Project has echoed these concerns as Budd-Falen returns to DOI. The project’s Grace Kuhn said Budd-Falen’s “long history of hostility toward federal agencies responsible for environmental stewardship makes her wholly unfit to lead the very department charged with managing the nation’s public lands.” Kuhn also noted Budd-Falen’s history causes much concern over her “ability to uphold the Interior Department’s mandate to steward public lands responsibly.”

The implications extend to marginalized communities. Housed within DOI is the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Tribal leaders have already criticized the Trump administration for funding cuts they claim violate treaty rights. Project 2025’s section on the BIA stressed more extractive industry on tribal lands, including reopening leases on lands that tribes have tried to protect from development.

When you add Budd-Falen’s support of county supremacy to this mix, the potential for harm to Indigenous communities only increases. Additionally, should the DOI allow commissioners and sheriffs to wield county supremacy at the local level, history has shown that the rights of people of color, people of lower income, and other historically marginalized communities will suffer.

Where militias and land-use fights intersect

Generally, there are two versions of county supremacy. The anti-environmental “wise use” version holds that the county commission should have ultimate authority in determining what is done with all the land within a county’s boundaries, including federal and state land. Supporters boast that local rural economies will improve because commissioners could allow extractive industry to circumvent state and federal land-use regulations. The second version of county supremacy, popularized by the antigovernment movement, centers on the belief that the sheriff is the supreme law enforcement officer of the land. These sheriffs, often called “constitutional sheriffs,” believe they ultimately get to decide which laws will, and will not, be enforced in their counties.

Frequently, especially at the local level, these two versions of county supremacy merge. In 1996, a police chief in Washington illustrated this, saying, “Sometimes I have a hard time telling where the militia starts and the land-use movement ends.” This sentiment was echoed by John Trochmann, a framer of the 1990s militia movement and founder of the Militia of Montana, who said in the early 2000s that the “wise use” movement fit within the goals of militias.

Federal law and regulation don’t support Budd-Falen’s assertions regarding county supremacy. A U.S. Forest Service attorney told the media in the early 1990s that her ideas were based on “bizarre theories.” A 2012 legal analysis of county supremacy commissioned by the Montana Human Rights Network (MHRN) detailed how local governments have no authority to change federal laws or rules, and they lack the authority to assume any control of federal lands.

These inconvenient facts never slowed down Budd-Falen. A High Country News report from 1992 cut right to the purpose of her work: “to bring the federal government to its knees.” Budd-Falen now brings these illegitimate theories and destructive goals to the highest levels of the DOI.

Central to county supremacy is the idea that public land only has value if users generate profit from its resources. Supporters want to open land to more ranching, agriculture, mining and timber operations. A long history of boom-and-bust cycles finds private interests extracting resources, declaring bankruptcy and leaving poor rural communities to deal with the literal mess left behind. The expansive, if incorrect, support of “property rights” under county supremacy is also used to attack tribal sovereignty, which is guaranteed to Indigenous people via treaty with the federal government. County commissioners and non-tribal members frequently use arguments grounded in “wise use” and county supremacy in an attempt to undermine tribal government jurisdiction over their own reservations.

The negative outcomes extend beyond arguments over land use. County supremacy empowers constitutional sheriffs driven by hard-right ideas. These sheriffs support mass deportation efforts targeting immigrants, face accusations of racism, and support efforts to repress the LGBTQ+ community. In the end, county supremacists view county commissioners and sheriffs as nullification agents to diminish, if not outright target, the rights of people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, people experiencing poverty and other traditionally marginalized communities.

Targeting the feds through county supremacy

Budd-Falen’s use of county supremacy to subvert federal land policies led Outside magazineto dub her the “godmother of the county movement” and for MHRN to call her “County Supremacy, Esquire.” Much of her infamous legacy started in New Mexico.

Beginning in the 1980s, New Mexico’s Catron County passed various illegitimate ordinances that empowered county commissioners to veto federal laws and regulations, in addition to allowing the county sheriff to arrest federal or state officials who attempted to enforce federal statutes. Media coverage at the time noted that the county’s commissioners had the support of activists who parroted antigovernment conspiracies, talked about forming militias, and sometimes advocated violence against federal land managers.

In the early 1990s, James Catron, Catron County attorney, enlisted Budd-Falen to help draft the local ordinances for the county’s legal warfare against the federal government. Her work in the county resulted in a set of seminal county supremacy ordinances that exemplified the doctrine in its rawest and purest form.

The federal government responded quickly, noting the county lacked the constitutional authority to order the U.S. Forest Service to do anything. It correctly declared that the ordinances existed “without legal effect” and were “null and void.” County officials were warned they faced federal felony charges if they tried to enforce the ordinances. Despite that, Budd-Falen kept peddling these ideas around the country through the National Federal Lands Conference (NFLC), a group that also operated at the nexus of the anti-environmental and antigovernment movements.

Budd-Falen served on the NFLC’s advisory committee during the 1990s. She wrote articles for the group’s newsletter and was referenced often in its publications. The NFLC held seminars and workshops throughout the West touting Catron-like ordinances, and Budd-Falen was often a featured speaker. At one seminar, she promised to tell audiences how “to control decisions by the federal government.” At another, she softened her rhetoric, admitting counties didn’t have “veto power” over the federal government but claiming they did have “coordinating authority.” Budd-Falen remained connected to the organization in recent years and was a listed speaker at the NFLC in 2017. When it comes to invoking the latter, MHRN’s legal memo noted the word “coordination,” and variations of it do appear in federal statutes and regulations. However, there isn’t an option that gives counties the ability to overrule federal policies.

NFLC brings antigovernment ideas to land fights

The NFLC frequently promoted other antigovernment ideas. The group dedicated the lead article of a 1994 newsletter to the necessity of militias. The article discussed how militias could be used against public officials and government agencies. “We cannot trust the federal government to look out for our individual freedoms,” the article read. Using a frequent antigovernment talking point, the NFLC said militias would be “the main defense against tyranny.” It warned the federal government that it should “let us alone or face the consequences.” The article included a section on how to form a militia, and the author thanked the Militia of Montana and included its contact information.

The NFLC promoted many of the same conspiracy theories as antigovernment groups. It warned supporters of the so-called New World Order, or world government, under the United Nations. It promoted the idea that martial law might be coming to the U.S., and it would be up to people with guns to fight it off. All of this was standard fare for militia publications of the time. The NFLC encouraged supporters to read publications by the pioneering hard-right conspiracist John Birch Society and the Fully Informed Jury Association, which claims juries can disregard evidence and find people innocent if they don’t like the law in question. The NFLC also sold books by antigovernment conspiracists, including Cliff Kincaid and W. Cleon Skousen.

A 1995 NFLC newsletter featured a front-page article by then-Sheriff Richard Mack of Graham County, Arizona, in which he declared gun regulations were “a calculated and carefully orchestrated effort to DISARM A NATION.” Mack became a rising star in the antigovernment movement when he sued the federal government over the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. The NFLC also sold materials by Mack, who became a pioneering founder of the constitutional sheriffs movement and founded the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association.

Budd-Falen and antigovernment ranchers

In addition to her time with the NFLC, Budd-Falen also served as an attorney in the 1980s for the Bundy family, who would become infamous for their high-profile armed standoffs in Nevada and Oregon with federal agencies over land-use issues. Budd-Falen claimed she had minor contact with Cliven Bundy about grazing allotments more than 20 years before his Nevada standoff. However, she told the Daily Caller the Nevada Bundy standoff showed how Americans react when the federal government acts like “citizens are subservient to political power.”

Cliven Bundy isn’t the only high-profile antigovernment rancher Budd-Falen has worked with over the years. Nevada rancher Wayne Hage helped found the NFLC and served as its president in the early 1990s when Budd-Falen was on its advisory council. Hage filed an unsuccessful $28 million lawsuit against the federal government over grazing rights that were rescinded because he ignored regulations. Hage unsuccessfully argued that he owned the federal land. The litigation lasted decades, and such militias as the Militia of Montana circulated updates about the case.

Budd-Falen’s fundamental approach echoes that of the antigovernment movement. “The Constitution does not give you rights,” she said at an event in 2002. “The Constitution is a document that stops the federal government from taking your God-given rights.”

Background provided air of legitimacy

Before the NFLC, Budd-Falen’s government and nonprofit work helped provide an air of legitimacy to her advocacy. She served in James Watt’s DOI during the Ronald Reagan administration and followed Watt to the Mountain States Legal Foundation (MSLF) in the late 1980s. Watt saw the battle over public lands as a religious struggle. On his side were Christians and capitalists standing up for American values. On the other side were environmentalists who he said believed God is embodied in natural forces and objects. He once told an audience that conservationists were “leftists who want to control your social behavior.”

Founded in the 1970s, the MSLF has been a central player in the “wise use” movement. Focusing primarily on the judicial arena, the group’s mission includes “protecting property rights and economic liberty” and “defending the right to keep and bear arms.” Its website complains about big government, saying, “Everywhere you look today, our liberty is under attack.”

While at the MSLF, Budd-Falen promoted county supremacy at an event with Watt, claiming county commissioners could create resource plans to steer federal decision- making. She told the crowd that if there were federal employees in the room offended by her ideas, she hoped they would quit their jobs.

Throughout her career peddling county supremacy, her legal theories rarely prevailed for her clients. Salon reported that Budd-Falen frequently loses in court, and her clients paid the bills. “She is effective at talking ranchers and even county officials into being parties for her lawsuits,” the article noted, “and then charges them handsomely for the privilege of losing in court.”

Special thanks to the Montana Human Rights Network’s research archives for contributing to this article.

Image at top: Attorney Karen Budd-Falen is pictured in 2017 at her law office in Cheyenne, Wyoming. (Photo illustration by the SPLC. Original image of Budd-Falen by Mead Gruver/AP; background image of the U.S. Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C., by J. David Ake/Getty Images)