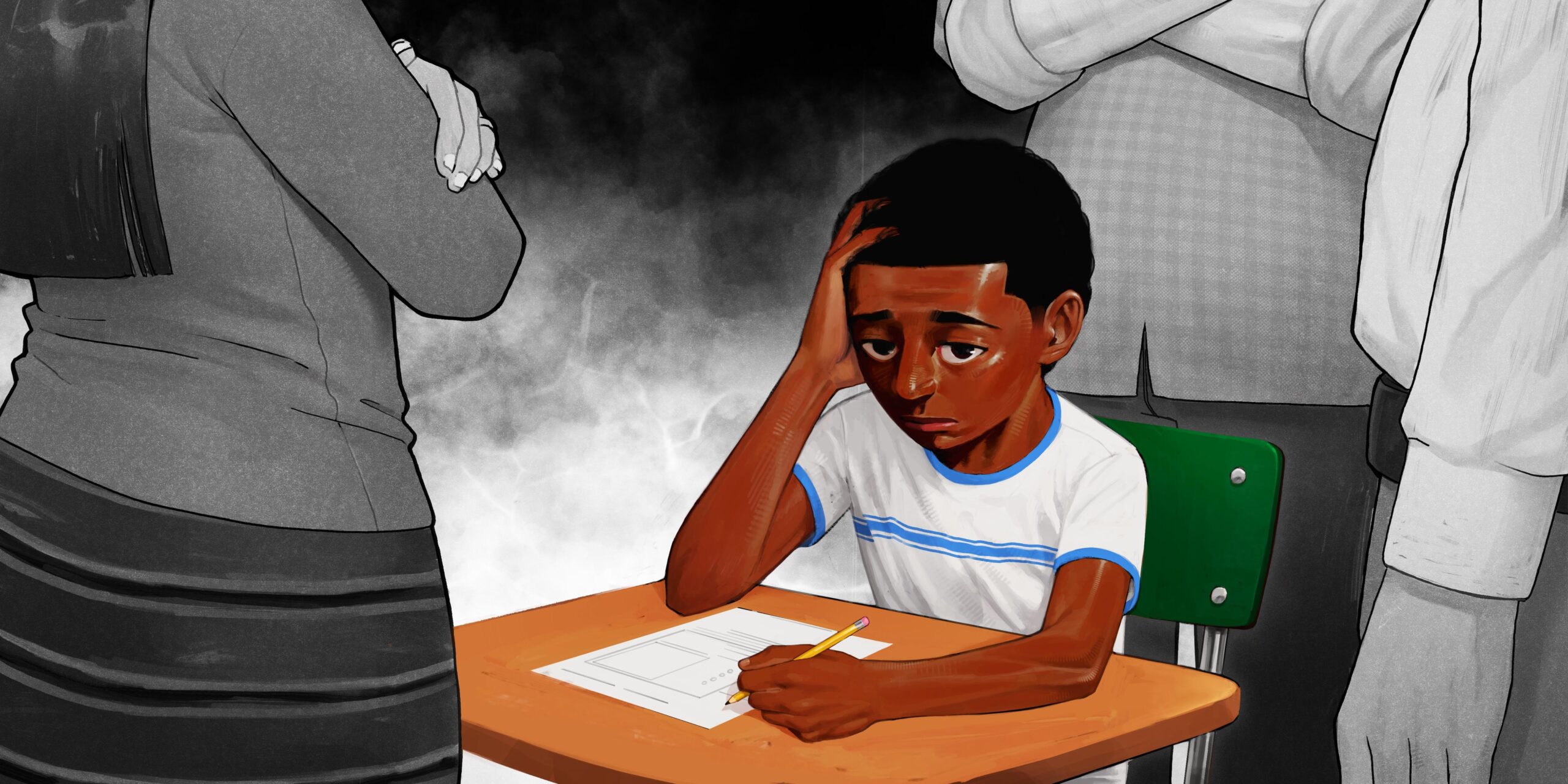

Thomas, a Black ninth grader from Louisiana, was required to transfer to an alternative school after he was shot. At the time of his exclusion, he had not been arrested or charged with any crime; instead, he was a victim of crime. After being discharged from the hospital, his home high school barred him from entering the school and forced him to accept a placement at a disciplinary alternative school for suspended and expelled students. Despite assurances that he could eventually return to his home high school, he spent months in a small, poorly resourced classroom without live instruction and was made to complete online classes alone at home. During this time, Thomas was prohibited from participating in sports, denied special education services, barred from attending prom, and disqualified from enrolling in specialized programs such as vocational classes and Advanced Placement courses.

Such stories, anonymized to protect privacy, show the need for accountability for supposedly “alternative” school programs serving students alleged to have engaged in improper or otherwise unsafe behavior. Where the resulting alternative placement is aimed to punish — or, more benevolently, “reform” — student behavior, it is a disciplinary placement. As a result, it should be treated under the law as such. Fifty years ago, in Goss v. Lopez,[1] the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that students have a right to due process before a suspension and expulsion. Those rights are no less important or salient today, when a suspension or expulsion for a student’s behavior results in the form of virtual school or an alternative school placement.

This report focuses on alternative schools in Louisiana, where attempts to improve the alternative education system — so widely used in Louisiana as a form of exclusionary discipline — have fallen woefully short. In 2017, the Louisiana Department of Education (LDOE) published an “Alternative Education Study Group Report” that introduced eight guiding principles focused on academic, behavioral, social, and emotional supports for students in alternative education programs. These principles have not been followed with fidelity, nor has data collected assisted public schools to reach a goal of improving alternative education. As this report will detail, Black students and students with disabilities remain overrepresented in alternative education, and schools fail to ensure that students in alternative education programs earn enough credits to progress toward graduation.

This report highlights the disparate education provided by alternative schools in Louisiana and in the Deep South more generally. It also aims to raise awareness about the connection between placement in alternative schools and the school-to-prison pipeline. This report hopes to spur change to address the separate and unequal system of education these school systems can create.

Background

Across the United States, publicly funded “alternative” schools aim to provide a different educational environment for students whose needs are not met by traditional school environments. The term “alternative school” may be used to describe charter schools, magnet schools, remote learning programs, or even juvenile detention centers. It is important to note that not all such alternative programs are punitive. This report addresses only those “alternative schools” that are intended for students who are pushed out of school for disciplinary reasons. In Louisiana, the state of this report’s focus, a state statute defines alternative education as existing for “disruptive” students, and, as a result, alternative schools in Louisiana are disciplinary by design.[2] Accordingly, this report will refer to disciplinary alternative schools generally as “alternative schools” in this report.

Beyond Louisiana, however, public school systems throughout the country transfer expelled or suspended students to disciplinary alternative schools — again, referred to in this report as alternative schools. The data shows that students at such alternative schools are at higher risk of academic failure, truancy, and failing to complete their degrees as a result of the lower quality of education and the lack of supervision provided in alternative school environments.[3] Once transferred, it can be difficult for these students to reenroll in a traditional public-school setting.

10,252Students sent to alternative education sites for suspensions from 2022 to 2023

In Louisiana, placement at an alternative school is required by statute for students who face long-term suspensions or expulsion.[4] Students with disabilities and students of color have long borne the disproportionate burden of these disciplinary exclusions. Black students in particular have been routinely over-punished and condemned for the same youthful student misbehavior in which their white counterparts engage. Louisiana’s Black students have been subject to school pushout at alarming rates, making them increasingly vulnerable to ending up in the youth justice system and having other negative outcomes. From 2017-2018, Louisiana had the third-highest out-of-school suspension rate (8.98%) and second-highest expulsion rate (0.81%) in the country, according to U.S. Department of Education figures — with its expulsion rate being over four times the national average. During that same period, more than one in eight Black students (13.2%) in Louisiana were suspended from Louisiana’s public schools.

Given these disproportionate rates of discipline, it is no surprise that disciplinary, involuntary transfers to alternative schools occur at disproportionately high rates to Black students and students with disabilities. With few exceptions, Black students and students with disabilities in Louisiana experience involuntary transfers to alternative schools at higher rates than their peers. For instance, in Louisiana’s 2015-2016 school year, 26% of the student population at alternative schools were students with disabilities and 85% were Black. This history of de facto segregation of Black students and students with disabilities at alternative schools, and alternative school students’ increased encounters with law enforcement, raises serious questions concerning such schools’ effectiveness in delivering education to their students, as well as the efficacy and equity of the school system as a whole.

And yet, students have significant rights under state and federal law before they can be transferred to a disciplinary alternative school. Every student is constitutionally guaranteed the right to notice and a hearing before suspension or expulsion, and many state constitutions and statutes, including in Louisiana, require the same.[5] Students with disabilities also have the right to a Manifestation Determination Review (MDR) meeting before the school can change the placement of a child with a disability for disciplinary reasons.[6] The requirement to hold an MDR applies to more than just students who have been identified as eligible for special education services and already have IEPs.[7] The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) also requires MDRs to be held for unidentified students with disabilities when the school district has “knowledge” of the disability.[8] Generally, this means that if the evaluation process started before the events giving rise to the disciplinary action, then the child has a right to an MDR before exclusion.[9] For more information about MDR meetings, please see our guide on “Helping Your Child with a Disability Get a Good Education.” The guide includes recommendations for local nonprofits that provide legal assistance to families and advocates learning to navigate these processes.

An Overview of Alternative Schools

As outlined in the SPLC’s Only Young Once youth justice report series, disciplinary alternative schools are an outgrowth of the “zero tolerance” discipline movement in the late 20th century. In general, schools across the U.S. adopted punitive disciplinary policies in the late 1980s and early 1990s, after zero tolerance policies became more popular following passage of the Gun-Free School Zones Act, signed into law by President George H.W. Bush in 1990. These policies were aimed at applying uniform punishment and decreasing misbehavior, drugs, and violence in schools; instead, they led to an increase in suspensions and expulsions, and worsened racial disparities in school discipline.

Today, these and other policies removing “disruptive” students from the classroom continue to fuel the placement of youth at disciplinary alternative schools. In Louisiana, for example, Dr. Cade Brumley and the Louisiana Department of Education recently issued a report called “Let Teachers Teach.” The report calls for placing “ungovernable students” at alternative sites for behavior support — in other words, placing students with behavioral disabilities, among other students, in a restricted, isolated, and segregated setting away from their peers. It also recommends removal of critical accountability metrics, such as suspension rates, which are required to prevent discriminatory exclusion of students with disabilities and students of color.

Only 37% of alternative schools

Are housed within regular schools or are separate schools; the rest are housed within other facilities. 17% of the non-school-based group utilized online instruction as the sole means of education — regardless of students’ ability or need.

Barbara Fedders, Schooling at Risk, 103 IOWA L. REV. 871, 899 (2018)

The trend extends well beyond Louisiana. For over two decades, officials in Georgia have advocated for alternative schools to separate children deemed “disruptive” from other youth. The result has been persistent racial disparities in alternative school placements, and highly detrimental outcomes for those youth. Once assigned to an alternative school, students are often made to navigate through instructional materials on their own, sitting at a computer while working through workbooks independently. A teacher may be there to answer questions and provide supervision, but is not necessarily there to lead class instruction. Frequently, youth in alternative schools are also often steered away from pursuing high school diplomas and onto GED tracks.

The persistent disparities in disciplinary alternative school referrals mean that students at alternative schools frequently face segregation.[10] Some students in alternative schools are housed in a separate classroom provided in the student’s traditional school, while others are transferred to programs provided at an entirely different school. In Louisiana, youth and families report that these schools are sometimes housed in courthouses, “boot camps” and other punitive or carceral settings. Indeed, in Louisiana, schools in juvenile detention are also considered alternative schools.

About five to 10 years ago, enrollment in alternative schools saw a general decline nationally, and that trend was reflected in Louisiana, particularly after LDOE issued its 2017 report with recommendations to reform alternative education. However, Black students and students with disabilities remain overrepresented when compared to student populations in traditional schools. Further research has shown that Black students and students with disabilities are not only overrepresented but have historically had longer stays than their white peers, and sometimes Latinx peers, in alternative programs. Despite the overrepresentation of Black students with disabilities in these schools, only about 39% of states have alternative education statutes related to students with disabilities.

From 2015-16

26%

Of the students alternative schools had disabilities

85%

Of students in alternative schools who were Black

These trends are reflected and further clarified in the 2019 report on alternative schools released by the Government Accountability Office (GAO); the GAO reported that national enrollment in all alternative schools declined by about 25% between the 2013-2014 and the 2015-2016 school years. However, about 75% of this reduction was due to declines in white and Latinx student enrollment, while declines in Black student enrollment only accounted for about 25% of the overall change. The report also found that enrollment of students with disabilities dropped by 12%, yet Black students and students with disabilities, particularly boys, remained overrepresented in alternative schools.

The impact of school districts failing to record alternative school placements also must be considered as a factor impacting statistics on alternative school enrollment. Students in disciplinary alternative schools are usually transferred to these programs involuntarily, but sometimes they report being coerced into “voluntary” placement.[11] For example, a school may threaten to mark an expulsion on a student’s permanent record, if a parent refuses to agree to an alternative school. These kinds of disciplinary alternative placements are not typically reflected in public reporting.

School suspensions and expulsions not only lead to involuntary transfers to alternative schools but also have led to arrests, referrals to law enforcement and involvement with the juvenile justice system. Since the beginning of the use of alternative schools, student arrests, police referrals, the juvenile justice system, and the suspensions and expulsions that lead to such involuntary transfers have been intimately linked.[12] Harris v. Atlanta Independent School System, a class action lawsuit filed in 2008, highlights how alternative schools can create highly punitive environments of violence and fear, including daily, invasive, and humiliating searches.[13] Children forced to attend the alternative school faced corporal punishment for failure to follow school orders; one plaintiff was punched by two teachers at the school to punish or discipline him for failing to obey an order to take his seat. Another police officer under the supervision of the school hit a different student on the leg with a police baton to punish him for leaving a classroom without the teacher’s permission. In this environment of fear, intimidation, and violence, students were not only unable to learn, but at much greater risk of disciplinary action, suspension, injury, and arrest than any other school.

Sometimes the mere accusation of criminal conduct is enough for a student to become entangled with the juvenile justice system, suspended, expelled, or involuntarily transferred to an alternative school. For example, in P.A. v. Voitier, a more recent case brought by the SPLC, a 15-year-old boy in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, was forced to attend the alternative school after an off-campus incident of violence in which he was shot. At the time of his exclusion, he had not been arrested for or charged with any crime. Still, school administrators threatened him with an expulsion on his permanent record if he did not waive his right to a due process hearing and attend the alternative school.[14]

Students in disciplinary alternative schools, such as the ones described in Atlanta and in St. Bernard, report not only a lack of extracurricular activities, lockers, and school materials like textbooks, but an abundance of surveillance, searches, and school resource officers (SROs).[15] In addition to the lack of tangible resources, alternative schools often have fewer support staff like nurses, psychologists and social workers. The inferior educational opportunities, lack of support, and over-policing of students in these schools all contribute to a greater risk of dropping out, which can limit a student’s employment prospects and increase the likelihood of poverty.

National trends of overutilizing alternative schools, racial imbalances with district demographics, and quality disparities with traditional schools are particularly on display in the SPLC’s focus states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi. A 2019 GAO report showed that alternative schools in Florida make up at least 5% of schools in many of the state’s school districts, with alternative schools making up at least 10% of schools in some of its districts. A report on alternative schools in Mississippi noted that a disproportionate number of the students placed into the alternative school setting were Black students and students with disabilities. The report found Mississippi alternative schools struggle to provide the resources needed to provide services to students with disabilities, citing the example of one county school in 2005 that provided none of the services described in its special education students’ Individualized Education Plans (IEPs).

Different states use different metrics to measure and identify underperforming schools and the student groups that need support. These differing metrics can mask the inferiority of alternative schools, especially disciplinary alternative schools, and obscure data that might be used to improve them. A 2020 GAO report on 15 states’ accountability systems for alternative school performance found that Georgia utilized college and career readiness metrics, extended-year graduation rates, and attendance rates to assess alternative school performance, while Florida used only college and career readiness metrics. Florida’s focus on career and college readiness omits performance assessments based on graduation rates or absenteeism and thus may not make Florida schools accountable for these measures. In addition to providing insufficient accountability metrics, Florida’s use of alternative schools run by private charter operators mask dropout rates and improve test scores at traditional schools by siloing low-performing students in alternative schools. The GAO report notes some Florida alternative schools may avoid accountability when students withdraw without graduating “by coding hundreds of students who leave as withdrawing to enter adult education, such as GED classes.” This Florida example suggests that accountability systems for alternative schools may not fully capture the severity of their failings.

For a more intensive view of disciplinary alternative education in the Deep South, it is instructive to look at the state of alternative schools in Louisiana, where alternative education is required for suspended and expelled students under state law.[16] In Louisiana, despite years of reform efforts, extreme disparities persist, as outlined below.

Data Analysis

Separate and Unequal Alternative Education in Louisiana

In 2017, the Louisiana Department of Education (LDOE) convened an Alternative Education Study Group (“Study Group”) to review alternative education services in the state and provide recommendations for improvement. The Study Group found that as of the 2015-2016 school year, although Black students made up 44% of the state student population, they made up 85% of the student population in alternative schools due to the overrepresentation of Black students in suspensions and expulsions. Students with disabilities were similarly overrepresented. Students with disabilities made up 11% of the state student population but 26% of students in alternative schools. The majority of students who attended these schools were involuntarily transferred into these programs for minor and sometimes arbitrary infractions, like being disrespectful or using profanity. A full 19% of students at these schools dropped out.

Although most states assign inexperienced teachers to alternative schools or use placement to these schools as punishment, Louisiana is the only state in the South that requires that teachers volunteer or consent to teaching at alternative schools.[17] Yet, the Study Group found that students at alternative schools still experience limited face-to-face teacher instruction, and that alternative schools fail to employ and retain trained teachers or otherwise provide professional development for teachers at alternative schools.

Despite the recommendations following this report, suspensions and expulsions in Louisiana remain high, and transfers to alternative schools continue to harm and isolate vulnerable students today. Furthermore, students continue to face arrests, referrals to law enforcement and entanglement with the juvenile justice system.

Since 1990, Louisiana school districts have been required by law to collect and report information about students suspended and expelled to alternative schools, including academic outcomes and educational services.[18] Based upon this data, as well as an independent study undertaken by the state, LDOE in 2017 released an “Alternative Education Study Group Report” discussing poor alternative education practices in Louisiana and creating Eight Guiding Principles for improvement.

- Effective alternative education.

- Transitional processes and supports.

- Appropriate and effective interventions and supports.

- Appropriate academic services and career readiness opportunities.

- Effective teachers and staff with comprehensive training on academic, behavioral, social and emotional needs of student.

- Consistent data collection.

- Prioritization of referrals to alternative education services.

- Community partnership development.

After a public records request (PRR), LDOE provided annual school year reports on alternative education since 2017.[19] These reports do not directly provide updates on the Guiding Principles, and the only data provided in some reports is demographic data. Unfortunately, but not unsurprisingly, the demographic data in each of these reports shows a disproportionately high number of male students, students with disabilities, Black students, and students with lower incomes.

The 2017 Guiding Principles brought to light substantial failures of Louisiana’s alternative education sites, including gaps in services and limited face-to-face teaching, as well as a lack of appropriate technology, career and technical options, academic counseling, and other services, leading to students at an alternative school in Louisiana being five times more likely than their peers to drop out of school. To the state’s credit, the 2017 report further sought to fix these issues through the set of guiding principles stated above, which are elaborated in action steps to reduce reliance upon alternative schools and improve services for students; however, these principles appear to have been abandoned.

Black students make up*

44%

Of the student population

85%

Of the alternative school student population

*- From 2015-16

Most recently, in a report called “Let Teachers Teach,” Louisiana State Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley and a statewide workgroup advocated for the “remov[al] [of] suspension rates as criteria within the school and system accountability model.” The workgroup producing this report recommends placing all “ungovernable middle and high school students at alternative school sites.” Essentially, the report supports allowing teachers to send all “ungovernable students” to alternative schools to maintain classroom order, instead of first implementing the required 2017 Guiding Principles interventions. This policy directly contradicts the 2017 report’s goal of alternative education as a last resort placement. And to the extent schools refuse to provide notice and a hearing for all students referred to an alternative school — or otherwise isolate and segregate with disabilities from nondisabled peers, without Manifestation Determination Review meetings (MDRs)[20] in alternative settings — such policies may violate federal and state law.

Meanwhile, the most recent LDOE reports show little effort at meaningful reform. There is no data or other evidence to show that students in alternative settings are receiving individualized academic services; transitional planning; individualized behavioral interventions and supports; intermediate interventions prior to alternative school placement; or aid from community partnerships for mental health and other services. And while a 2022-23 report from the state notes that 42.9% of alternative schools achieved the highest level possible for student achievement and resulting career and technical education opportunities, 49.9% achieved the lowest three levels on the Strength of Diploma scale, a measure collected by the state describing how well school prepares students for postsecondary education. Further, the most recent LDOE report from 2024 confirms that credit recovery success in alternative programs is weaker than envisioned by the guiding principles, with “students [only] averaging about four (4) credits while attending [alternative education] sites.”

Unfortunately, due to this abandonment, Louisiana’s alternative education system is still facing the same issues of inequity and educational failure, including poor academic outcomes for many students, and high numbers of students leaving alternative schools without a diploma. The current policy proposals by state government to place more students at alternative schools threaten to exacerbate these inequities.

Report Card: The Current State of Alternative Education in Louisiana

The analysis of alternative schools and programs in Louisiana from 2018 to 2023 reveals important trends regarding student discipline, performance, and outcomes. Most importantly, the number of students sent to alternative schools for disciplinary reasons remains high. In the 2022-2023 school year, there were 10,252 students sent to alternative education sites for suspensions. Meanwhile, although there have been overall reductions in the student populations of alternative schools since 2018, the total count of students sent to alternative education sites due to expulsions rose from 4,801 in 2018-2019 to 5,045 in 2022-2023. These trends suggest that while there may be some reductions in disciplinary transfers to alternative schools overall, the reliance on alternative education for addressing student behavior remains substantial.

These rates of alternative education referral track exclusionary discipline figures. While suspensions decreased significantly between 2018 and 2022, they saw a rise again in 2022-2023. Overall suspension rates also increased at all grade levels from the 2021-22 school year to 2022-23. The overreliance on alternative education for students from these groups underscores the systemic issues in addressing their needs, including insufficient behavioral interventions, bias in discipline practices, and a lack of appropriate academic and social emotional supports.

Academic outcomes for students in alternative education programs remain concerning. Despite an increase in the number of students receiving diplomas (404 in 2018-2019 to 519 in 2022-2023), the number of students dropping out remains high. Roughly 890 alternative high school students dropped out in 2022-2023, and this is twice the number of students who received diplomas in previous years. The average credits earned by students while at alternative sites remained stagnant, with students earning an average of just over four credits across all years.

Only Black Students

In the majority-white Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana, no white students received law enforcement referrals from alternative schools in the 2021-22 school year.

The burden of this academic deprivation is borne disproportionately by Black students. On average, in 2022-2023, Black students made up 71% of the alternative school population, compared to only 42% statewide. Meanwhile, students with disabilities identified under the Americans with Disabilities Act[21] represented 13.5% of the population in alternative schools, which is approximately double the average of 6.8% statewide. In some school districts, the disparities were even more stark; for example, in Tangipahoa Parish, only Black students — and no white students — in a majority-white parish received law enforcement referrals from alternative schools in the 2021-2022 school year, according to data the SPLC requested from the school district. Without the SPLC’s direct request for this data from the school district, this information would have never become public.

Such severe inequities are reflected across other parishes as well. In East Baton Rouge, Black students account for 69% of total enrollment but represent 86% of out-of-school suspensions and an alarming 94% of expulsions. Similarly, in Caddo Parish, Black students make up 64% of enrollment but account for 82% of out-of-school suspensions, 89% of expulsion, and 80% of law enforcement referrals. These rates far exceed the statewide averages for Black students and highlight the disproportionate use of punitive disciplinary measures against them, including alternative school placement following suspension or expulsion.

Additional district-level data confirms the harmful impact of these racial disparities. For example, 82% of students held back in East Baton Rouge Parish are Black. Meanwhile, Black student representation in Advanced Placement (AP) courses remains persistently low across most parishes. In Tangipahoa Parish, Black students comprise 47% of total enrollment but only 20% of AP enrollment. Similarly, in St. Charles Parish, Black students make up 32% of enrollment but only 20% of AP enrollment. This stark underrepresentation in AP coursework reflects inequities in access to advanced academic opportunities and resources. Such disparities are only exacerbated in alternative school settings, where students can lack access to AP courses.[22]

Stories From Families

To supplement these statistics, the authors of this report spoke with 24 families in a focus group with a Spanish interpretation option. There were two qualified facilitators conducting the focus group. The duration of the session was 90 minutes. There was an online survey distributed to parents, community members and school providers/advocates to complete. The following graphic illustrates the detailed information of participation in the survey.

The SPLC also convened a focus group of Louisiana alternative education stakeholders on April 29, 2024. This 90-minute discussion was attended by 24 participants primarily from East Baton Rouge Parish, Jefferson Parish, and Madison Parish. The session explored key issues critical to discerning the challenges that students and their families face navigating the alternative education system. The discussion underscored the importance of addressing challenges in alternative education settings to better serve these system-impacted student populations.

Comments from survey participants

“[Students in] alternative schools are treated [poorly] like special education [students] before the passage of [P.L. 94-142 (the precursor of IDEA)]. They are typically housed in some of the worst facilities.”

(Terrebonne)

“The school system likes to retaliate on parents when they’re advocating or fighting for their children’s rights. You always have to have an outside source like a lawyer [if your child is sent to an alternative school].”

(East Baton Rouge)

“Madison Parish does not follow the legal guidelines set forth when it comes to expelling students. My child has been sent to an alternate setting over [45] days yet I have not attended an [Manifestation Determination Review] meeting. My requests to have him reevaluated have been ignored. I have been asking for a reevaluation for over a year but instead the school continues to remove him from school.”

(Madison)

“[The alternative school] looked like a literal jail. It even had bars that resembled the ones in jail. There were no staff or teachers there to greet the children in the morning other than a[n] SRO [school resource officer] or security guard. It was not a nurturing environment for any child […] .”

(Ascension)

“The alternative school is like sending your child to jail. And just like jail, if you do not receive any mental health services or social skills in a positive manner[,] then you will get repeat students.”

(Calcasieu)

“Counseling services were extremely limited [in the alternative school], whereas for the students enrolled in the alternative school, their needs were nearly unlimited. The resources [in the alternative school] […] don’t match the need [… ]. They match the availability of those resources […] which dooms the alternative school program and those in it to fail.”

(Terrebonne)

Discussing their experiences with alternative schools in their parish, participants highlighted challenges including:

- Lack of qualified teachers.

- Inadequate services for students with special needs.

- Issues with transitioning in and out of alternative schools.

- Students’ experience of trauma.

These stakeholders expressed the lack of:

- Concern.

- Resources.

- College courses.

- Teachers.

- Due process for their students attending alternative schools and programs.

Comments from survey participants

“They placed him into alternative school, and there was no discussion before he was placed into the school about credits, graduation. No, there wasn’t even a school meeting.”

(Forum participant)

Participants conveyed frustration with school- and district-level administration of alternative education programs.

- One parent described the academic and mental health disruptions experienced when her child was placed in an alternative school at a critical milestone of senior year.

- Another participant discussed their child’s struggles with trauma and mental health issues in alternative schools, emphasizing that the need for individualized support and adherence to IEPs were lacking in the school placement.

The focus group discussion underscored the importance of addressing challenges in alternative education settings, with participants expressing their frustration towards school administration in multiple parishes. Many parents and former students shared their personal stories, highlighting systemic issues and the negative impact on their children’s educational experiences.

- One parent, William (pseudonym), described his challenges with getting proper support for his child’s serious medical condition. Eventually, with the help of a lawyer, he transferred the child out of that school district.

- Participant Jane (pseudonym) described a negative experience involving her child with autism being suspended and not receiving proper support and accommodations at school. She highlighted the lack of understanding and support for children with disabilities in the education system.

Comments from survey participants

“Unfortunately, on the short-term side of alternative schools, they do not accept IEPs, they don’t provide the accommodations. They didn’t even give her modified work to take to the discipline center with her. So it was just a horrible experience. And I do think that they need to do better by our children with, you know, disabilities and the children who are in special education. So that’s my experience.”

(Parent speaking about student with autism, Behavior Intervention Plan and IEP and placed in alternative school settings after disciplinary action)

The major concerns expressed by participants included a lack of special education services, inadequate academic/mental health support, utilizing independent studies as a default school placement, insufficient resources, and poor communication between school officials and families. The disruption of academic status and instability of alternative schools was stated best by a parent who provided the following explanation about her child’s course placement experience.

Comments from survey participants

“He was taking chemistry at the time, and he had a B in it before he ended up in the alternative school. When he got there, they did not have a teacher for chemistry or biology or physics.”

(Parent speaking of child’s experience with alternative school in Jefferson Parish)

The collective sentiment underscored a pressing need for significant reforms to ensure that alternative education settings and transition processes fulfill their intended role of providing a supportive and effective learning environment for all students.

Comments from survey participants

“There’s not enough teachers. Sometimes they just sit around. They’re not getting their related services. And when they exit, they don’t get transitioned properly, um … and when they exit, I’ve heard many times they’re more traumatized, and then when they went in.”

(Parent speaking of student experience and teachers)

Retaliation was a recurring theme among the parents’ testimonies. They reported feelings and actions of retaliation from school officials when advocating for their children’s rights to a proper education. These parents and community stakeholders provided detailed instances of intimidation, stigma and punitive measures taken against them, which not only hindered their efforts to secure necessary educational services but also exacerbated their frustrations and sense of injustice.

Comments from survey participants

“The stigma of being sent to the alternative school was harsh, and how his peers perceive him after spending time at the alternative school. So I think that the social emotional impact, the lack of academic support, the lack of accommodation, the lack of the experienced or certified teachers who were able to help him meet his graduation requirements, all that was really, like, has a negative impact on him, and he ended up not going to college.”

(Parent speaking of child experience in alternative school)

Recommendations

The current state of alternative education in Louisiana shows the dire need for a stronger focus on academic interventions and behavioral supports within both alternative and traditional school settings, as well as alternative conflict resolution and restorative justice programs. In Louisiana, the persistently low credit accumulation and dropout rates, coupled with the disproportionate representation of Black students and other vulnerable groups, highlight the ongoing challenges in the alternative education system. The stories and quotes shared through the focus groups and surveys also indicate the carceral nature of disciplinary alternative schools in Louisiana, including alternative schools in juvenile detention and the segregated, underresourced, and heavily surveilled alternative schools in the community.

A more holistic approach that emphasizes individualized, culturally sensitive support, mental health services, and effective behavioral interventions is necessary to better serve the disproportionately Black and Brown students, as well as students with disabilities, who are most at risk of dropping out or becoming entangled with the criminal legal system, before they arrive in an alternative school program. These supports cannot be provided in an environment where Black and Brown children, along with children with disabilities, are segregated. This approach not only fails to keep all students safe but also denies children an education as required under state law.

Stakeholders across a range of agencies and roles — local school districts, the Louisiana Department of Education, and parents and advocates — must take action to safeguard the rights of students placed at or at risk of placement at alternative schools. This report recommends the following actions.

- Before a transfer to an alternative school for disciplinary reasons, school districts must provide due process required under state and federal law, including suspension and expulsion hearings.

- Students with disabilities must receive a Manifestation Determination Review (MDR) meeting as required by state and federal law as well before alternative school transfer.

- To ensure such procedures are followed, districts must adopt policies to ensure due process before alternative school transfer; to eliminate forced waivers of students’ due process rights; and to prevent children from languishing at alternative schools beyond a set exit date. For an example of such policies, please see Appendix, a settlement agreement the SPLC reached on these issues in the past year with St. Bernard Parish Public Schools.

- Placements at alternative schools for disciplinary reasons must be reported as suspensions and expulsions to the state and federal government, even if a suspension or expulsion is not recorded on a child’s educational record. This too is required by the St. Bernard Parish settlement agreement.

- School districts and the Louisiana Department of Education must recommit to the 2017 Guiding Principles to improve the state of alternative education in our state. To track their progress, school districts and the state departments of education, including the LDOE, must also develop systems to accurately track data about students sent to alternative schools.

- Advocates and parents should prepare to defend their rights under state and federal law to disciplinary protections when faced with disciplinary alternative school transfers. Whatever the school district’s reasons for placing the child at an alternative school, parents and advocates should consider whether a suspension or expulsion hearing is appropriate, and then exercise their rights to appeal any decision from those hearings.

- Parents and advocates should also consider if the child has an identified or suspected disability that requires them to receive an MDR meeting before placement at the alternative school.

Acknowledgments

This report is a joint effort of the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Loyola University College of Law Stuart H. Smith Law Clinic.

The report was authored by Ashley Dalton, Lauren Winkler, Sophia Mire Hill, Claire Sherburne, Luz Lopez, Susan Meyers, and Mike Tafelski of the Southern Poverty Law Center; Hector Linares, Sara Godchaux, and Cait Roberts of the Loyola University College of Law Stuart H. Smith Law Clinic; Lauren Sneed of San Francisco State University; Amir Whitaker; and contributors from the Law Firm Antiracism Alliance, as detailed below. The Southern Poverty Law Center also thanks the Gilead Foundation for its funding of this project.

With contributions by Law Firm Antiracism Alliance members, including Briana Bell, Tamara Caldas, Zeynab Warraich, Hunter Payne, and Drew Evans at Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP; Rebecca Cazabon, Jasmine Brown, Madeleine Rodriguez, Devyn Parry, and Valerie Orellana at Foley Hoag LLP; Drayden Burton and Will Miller at Wyatt, Tarrant & Combs LLP; and Rebecca Broches, Matthew Smith, Michael Faikes, Samantha Mita, Emeka Nduka-Eze, Minji Kim, James Lathrop, Jenna Benz Conaway, Benjamin Kurrass, Gregg Katz, and Carolyn Rosenthal at Goodwin Procter LLP.

We also thank the anonymous families and providers who completed the survey and courageously shared their experiences in our forum. We would like to thank as well former deputy legal director of the SPLC Democracy: Education & Youth practice group, Bacardi Jackson; former SPLC interns Naomi Hodges and Amelia Patrick; former SPLC litigation advocate Jaclyn Cole; Michele Aronson, Noel Guerby, Kerry Cooperman, Paul Lee, and Peter Wilson Jr. of the Law Firm Antiracism Alliance; Austin Sprinkles of the UCLA Civil Rights Project; Alice Garcia of edCount; Katherine Dunn; Lauren Johnson of the St. Charles Care Center; and Alexa Bolden of Families Helping Families of Northeast Louisiana.

- Appendix: St. Bernard Parish Settlement Agreement

This report includes hyperlinked citations instead of full endnote citations. Full endnote citations, however, are available here.

Illustration at top by Ladon Alex.

[1] 419 U.S. 565 (1975).

[2] La. Rev. Stat. § 17:100.5(A) (“Parish and city school boards, with the approval of the State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, may establish and maintain one or more alternative schools for children whose behavior is disruptive.”). Louisiana is not the only state that defines alternative education in this manner. For example, according to Georgia statute, traditional schools should “reassign disruptive students to an alternative education program rather than suspending or expelling such students from school.” GA Code § 20-2-154.1(a).

[3] I. India Geronimo, Deconstructing the Marginalization of “Underclass” Students: Disciplinary Alternative Education, 42 U. Tol. L. Rev. 429, 436-38 (2011) (detailing how lack of adequate instruction in alternative school led to low proficiency in important school subjects like math and science and subsequently increased the rate of truancy and dropouts).

[4] Louisiana Rev. Stat. § 17:416.

[5] Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 (1975); see also La. Rev. Stat. § 17:416. Whether or not a suspension or expulsion that results in an alternative school placement requires due process under the U.S. Constitution is the subject of some debate. However, it is worth noting several decisions in the states served by the SPLC, including Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi, where federal courts have expressed support for students having rights to due process in this situation. See Cole v. Newton Special Mun. Separate Sch. Dist., 676 F. Supp. 749, 752 (S.D. Miss. 1987) (“A student could be excluded from the educational process as much by being placed in isolation as by being barred from the school grounds.”), aff’d, 853 F.2d 924 (5th Cir. 1988); Riggan v. Midland Indep. Sch. Dist., 86 F. Supp. 2d 647, 655 (W.D. Tex. 2000) (finding plaintiff raised a genuine fact issue as to whether alternative placement amounted to an effective deprivation of access to education “because [the student] was prohibited from participating in or benefitting from comments of his teacher and peers”); see also C.B. v. Driscoll, 82 F.3d 383, 389 (11th Cir. 1996) (suggesting a viable due process claim where education at an alternative program is so “inferior [as] to amount to an expulsion from the educational system”).

[6] 20 U.S.C. § 1415(k)(1)(E); 34 C.F.R. § 300.530(e).

[7] To obtain an IEP, a child must prove they have a disability within specifically delineated categories and that, because of that disability, they require special education services. 42 U.S.C. 1401(3)(A). Eligible categories of disability include: “intellectual disability, a hearing impairment (including deafness), a speech or language impairment, a visual impairment (including blindness), a serious emotional disturbance (referred to in this part as “emotional disturbance”), an orthopedic impairment, autism, traumatic brain injury, another health impairment, a specific learning disability, deaf-blindness, or multiple disabilities.” 34 C.F.R. § 300.8(a)(1); see also 20 U.S.C.A. § 1401(3)(A)(i) (West 2017) (describing disability categories under the IDEA).

[8] 20 U.S.C. § 1415(k)(5); 34 C.F.R. § 300.530(d).

[9] 20 U.S.C.A. § 1415(k)(5)(B). Exceptions to this rule exist where the parent refuses an evaluation or IEP services, and where the child has been evaluated but previously determined ineligible. Id. § 1415(k)(5)(C).

[10] Michelle Reichard-Huff & Perry A. Zirkel, Commentary, State Laws for Alternative Education: An Updated Policy Analysis, 305 Ed. Law Rep. 1, 5 (2014).

[11] Maureen Carroll, Racialized Assumptions and Constitutional Harm: Claims of Injury Based on Public School Assignment, 83 Temp. L. Rev. 903, 904-05 (2011) (discussing the case history related to the due process requirements for students who are involuntarily transferred to disciplinary alternative schools).

[12] See, e.g., Buchanan v. City of Boliver, Tenn., 99 F.3d 1352 (6th Cir. 1996).

[13] Complaint ⁋ 138, Harris v. Atlanta Independent School System, 08-cv-1435 (N.D. Ga. Mar. 31, 2009).

[14] Second Amended Complaint ⁋⁋ 72-100, P.A. v. Voitier, ECF No. 44, No. 2:23-cv-02228 (E.D. La. May 20, 2024).

[15] Barbara Fedders, Schooling at Risk, 103 Iowa L. Rev. 871, 899 (2018) (reviewing the lack of educational resources but abundance of SROs in alternative schools).

[16] La. Rev. Stat. § 17:416.

[17] La. Stat. Ann. § 17:100.5(c)(1) (2023) (“Teachers employed in alternative schools established pursuant to this Section shall be selected from regularly employed school teachers who volunteer.”); see also Reichard-Huff & Zirkel, supra note 12, at 6-8 (providing an evaluation of states statutes related to alternative schools, including staffing).

[18] Since 1990, La. Stat. Ann. § 17:7.5(D) regarding monitoring of alternative schools has required the Louisiana Department of Education (LDOE) “through an interagency monitoring process as established by the State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education [(BESE)] … [to] report annually on the effectiveness of [Alternative Education (AE)] programs to the governor and to the House and Senate Committees on Education.”

[19] Some of LDOE and BESE’s yearly reports to the governor and to the House and Senate Committees on Education before 2017 are easily found on the internet. See La. Stat. Ann. § 17:7.5(D); see also e.g.,

- La. Department of Education, Report to the Governor and the House and Senate Committees on Education: Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs SY 2013-2014 (2015), https://www.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/9SBS9H7197A5/$file/AGII_3-4_2013-14%20Alternative%20Education%20School%20and%20Program%20Report_Jan2015.pdf;

- La. Department of Education, Report to the Governor and the House and Senate Committees on Education: Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs SY 2015-2016 (2016), https://www.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/ACBSNZ7391E4/$file/AGII_4.1_AltEd_Report_Aug_2016.pdf;

- La. Department of Education, Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs School Year 2016-2017 (2017), https://www.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/ARWL9S558289/$file/AGII_2.1_Alternative_ed_annual_report_Oct17.pdf.

These reports list the AE site names, the number of students in AE, numbers explaining why the students are in AE, and the number of students exiting AE. These reports lack all necessary data, but the SPLC was unable to easily even find surface level reports such as these for every year after 2017. Because of this, the SPLC placed a public records request to try and obtain more information about AE sites during these years.

In response, LDOE sent the reports from 2017 to 2023, and some of the reports contained the surface-level data mentioned above while others contained more detail. See:

- La. Department of Education, Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs School Year 2017-2018 (2018), https://go.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/B58KFC50B383/$file/AF_7.2_2017-18_BESE_Annual_Report_on_AE_FINAL.pdf;

- La. Department of Education, 2018-2019 School Year Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs (2019), https://go.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/BJNPE76436F1/$file/2018-2019%20BESE%20Annual%20Report%20on%20AE%20-%20FINAL.pdf;

- La. Department of Education, 2019-2020 Academic Year Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs (2021), https://go.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/BWZTY9758E6D/$file/AF_6.1_Alt_Ed_Report_BESE_Jan2021.pdf;

- La. Department of Education, 2020-2021 Academic Year Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs (2022), https://go.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/C9SVYM830B0E/$file/AF_AlternativeEducationReport_Jan2022.pdf;

- La. Department of Education, 2021-2022 Academic Year Report on Alternative Education Schools and Programs (2023), https://go.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/CMTUP671633F/$file/AF_5.2_2021-2022_Annual_AE_Report_(Final).pdf;

- La. Department of Education, 2022-2023 Academic Year Report: Alternative Education Schools and Programs 2-4 (2024), https://go.boarddocs.com/la/bese/Board.nsf/files/CZ7Q4M658B1E/$file/AF_6.1_Alternative_Education_Programs_Report_Jan2024.pdf.

[20] A Manifestation Determination Review (MDR) meeting is required under the Individuals with Disabilities Act to prevent a child with a disability from being excluded for more than ten (10) days for behaviors related to their disability — the results of which can be appealed to an administrative due process hearing, and, ultimately, to state or federal court. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(k); 34 C.F.R. § 300.530(e).

[21] The above statistics reflect data for students with 504 Plans. Louisiana Department of Education, 2022-2023 Academic Year Report at 6. Other students with disabilities, including students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) represented 13.6% of the alternative school population, higher than the 11.8% average statewide.

[22] Where other school districts were able to respond to the same request, this response raises concern about the potential lack of a system to accurately record information about alternative school transfers in the school district.