Terra Boyd, a former New Orleans-area teacher, has spent the past two years of her retirement fighting for her grandson against his public charter school.

The school, she says, has failed to educate him under the terms of his Individualized Education Program (IEP) — a violation of federal laws for children with disabilities.

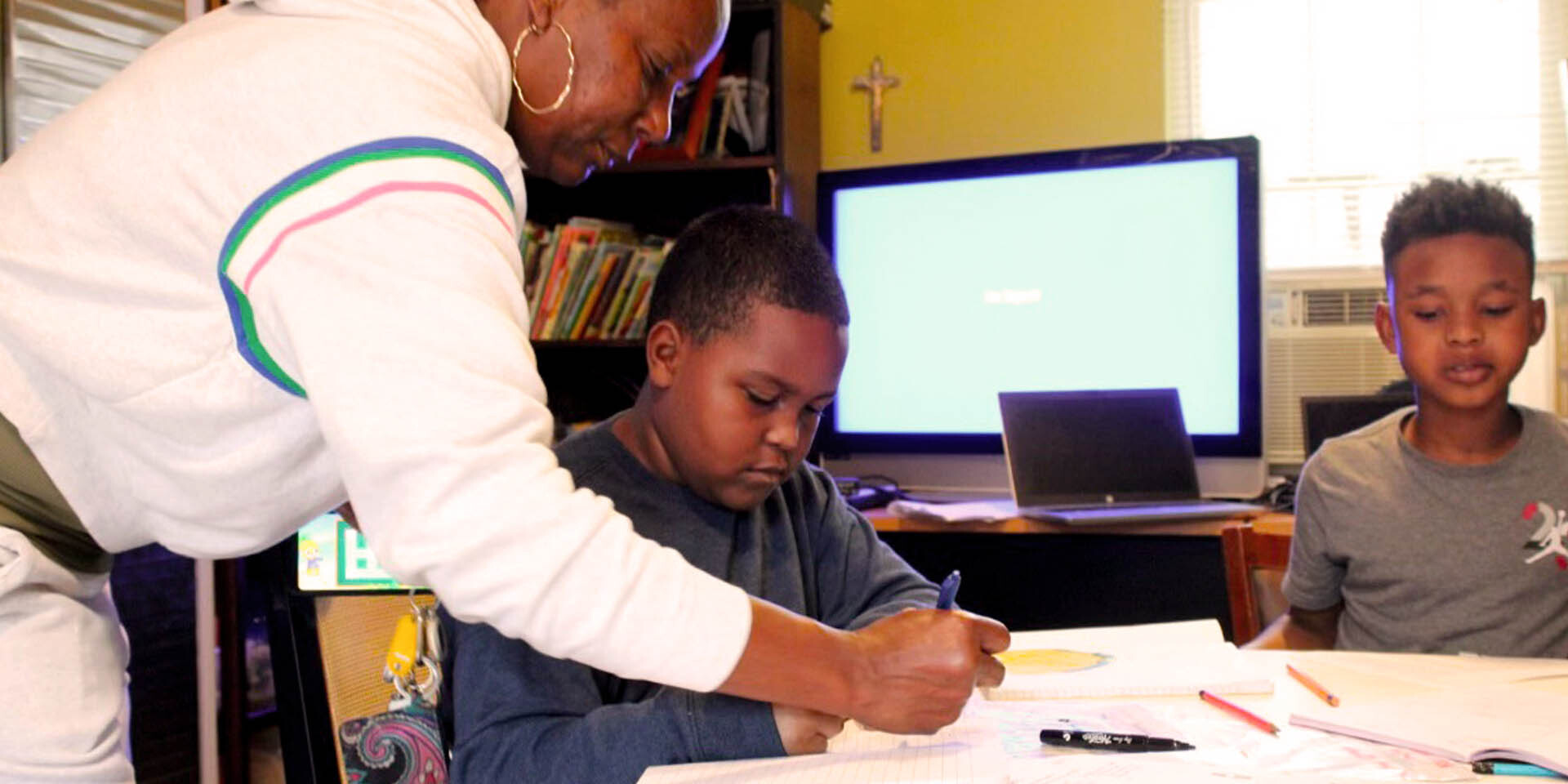

Boyd even started a nonprofit tutoring program for him and other young students with disabilities to fill the void the school would not.

Her 9-year-old grandson, T.B., was diagnosed with autism before the age of 2 and has trouble understanding abstract concepts. If a teacher gives him a story to read that says, “‘It’s raining cats and dogs,’ he takes the figurative language literally until the teacher explains the meaning to him,” Boyd said.

“Without one-on-one classroom help, he becomes confused and agitated and loses focus,” she said. The problem, Boyd added, and the reason she started the nonprofit Moving Challenges for Students with Disabilities, “is that giving him the special education services he needs should not be so hard. Parents shouldn’t have to bring in state mediators, have students evaluated by both the charter school and independent evaluators and hire a lawyer.”

T.B. is one of thousands of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, schoolchildren whose special education needs have not been sufficiently met to justify the parish’s release from independent monitoring under a 2015 settlement in the lawsuit P.B. v. Brumley. The Southern Poverty Law Center and co-counsel filed the class action lawsuit in 2010. The suit, representing 4,500 parish students with disabilities, charged the state with violations of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Under the settlement, the defendants agreed to oversight from an independent monitor until they have achieved two consecutive years of compliance. They have now asked the court to end the monitoring, but the SPLC told the judge in late March that the defendants haven’t fully complied with the settlement.

“It’s clear from parents, the independent monitor and community advocates that students still aren’t getting the special education services to which they are entitled or their IEP isn’t appropriate for them,” said Lauren Winkler, senior staff attorney for the SPLC’s Democracy: Education and Youth litigation team.

Reports from the Louisiana Legislative Auditor’s Office, while showing some progress post-Hurricane Katrina, also support the SPLC’s position.

In 2021, the SPLC released a guide, “Helping Your Child with a Disability Get a Good Education,” to help parents of children with disabilities hold schools accountable.

“There has been some improvement in area of the consent judgment since 2015, but there is a long way to go. The monitor has to stay in place for there to be an additional layer of accountability for the school system,” Winkler said.

Despite Boyd’s assertion that Bricolage Academy hadn’t followed her grandson’s IEP, in August 2024 the Louisiana Department of Education ruled against her and her daughter’s formal complaint against the school, which has been the subject of numerous complaints over the years by parents of children with special education needs.

Principals and teachers who don’t understand special needs will see a child who is very smart and articulate and will not understand that the child has disabilities that you can’t see. … They think behavior is the problem, not [post-traumatic stress disorder] or a mental health issue.”

Ashana Bigard, child advocate and co-founder of the Erase the Board Coalition

When T.B. starts fourth grade in August, his mother will send him to a different school. After T.B.’s mother notified the school system that this would be his last year at Bricolage, the school granted Boyd and her daughter 90% of the services they requested for T.B. during the past two years — starting next term.

“I think the reason they did that is so they look good,” Boyd said. “They know he’s moving to another school, and [they] won’t have to provide the services.”

Still, Boyd continues to organize Bricolage parents who have run into the same issues and adamantly agrees that the monitor must remain.

Root causes

As the SPLC pursues court approval for continued monitoring, an effort to centralize special education services for students with disabilities is ongoing.

Jennifer Coco is interim executive director of the Center for Learner Equity (CLE), a national education nonprofit developing a pilot program for centralizing special education services in Orleans Parish. Coco was among the SPLC’s original attorneys on the case. She litigated the 2010 lawsuit until 2018.

The lawsuit and subsequent filings acknowledged the effects of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 on the district’s problems delivering special education services. After Katrina, the state took over and closed the failing school system. It fired all teachers, staff and administrators — about 7,500 employees. The state did not hire back parish teachers, instead hiring novice teachers from the Teach for America program.

The state reopened Orleans Parish public schools in 2006 as charter schools, which were treated as 80 self-contained school districts. In 2024-25, the parish had 68 individual school districts.

“For students with disabilities, the New Orleans school district is the most decentralized in the entire country,” Coco said.

That decentralization makes it difficult for students with disabilities to obtain the services they need because each charter school controls its own special education services and compliance.

Coco’s group is partnering with the Orleans Parish School Board to create an agency that any charter school could join, and that agency would coordinate shared special education services for its charter school members. The plan calls for a small pilot program in the 2025-26 school year with possibly 12 of the parish’s 68 charter schools. Schools will still have to uphold federal disabilities laws, however. The agency will not conduct monitoring and compliance.

Child advocate Ashana Bigard is a co-founder of the Erase the Board Coalition, a group of New Orleans parents, educators and advocates. The group is pushing for an education committee to form an independent monitoring system, including a team that would visit schools, attend school board meetings, speak with parents and students, review school policies and speak with educators. It presented a proposal to the New Orleans City Council two years ago, but members have not acted on it.

“From principals to charter school CEOs to teachers who went through Teach [for] America and don’t know disabilities law, they don’t understand adolescent brain development and best practices and certainly don’t understand special education services for students with special needs,” Bigard said. “They may also still operate zero-tolerance policies. Special needs students can’t operate on zero tolerance. Their literal diagnoses don’t allow them to follow rules.”

Adding to the challenges for families with children who have learning disabilities is the complex intersection of race and poverty in the state, Coco said. In Louisiana, the second-poorest state in the nation, schools also suffer from a dire shortage of certified teachers. Orleans Parish has one of the lowest rankings for children with special education needs based on its limited resources, services and support systems. Black children comprise 93% of the Orleans Parish school district, and 91% of them are economically disadvantaged.

“Children growing up poor in New Orleans navigate homelessness, food insecurity and exposure to traumatic events in disproportionately high rates compared to children in other cities,” Coco said. “When you factor in disability in school, parents of New Orleans children with disabilities can end up fielding frequent phone calls from school expecting them to pick up their kids. This is a real strain on working families.”

And as Bigard noted, even when parents have the time to deal with administrators and teachers, those school officials might not understand the needs of a student with disabilities. That lack of understanding, coupled with teacher frustration and lack of sufficient oversight, can still lead to the kind of cruel discipline of students that the SPLC’s original lawsuit described.

Bigard recalled that in one case from 2023, a 16-year-old with a traumatic brain injury and bipolar disorder was placed alone in a windowless, closet-like space where his teacher told him to work, despite the fact that his IEP said he needed an assistant. The student’s mother didn’t believe him, so he recorded a video of himself trying to escape.

“Principals and teachers who don’t understand special needs will see a child who is very smart and articulate and will not understand that the child has disabilities that you can’t see,” Bigard said. “They think behavior is the problem, not [post-traumatic stress disorder] or a mental health issue. That’s one of the most common issues with kids who are not treated for their special education needs. The parents may already have an IEP in place, but a lot of times it’s not honored.”

Image at top: Terra Boyd works with a student at Moving Challenges for Students with Disabilities, a nonprofit tutoring program in New Orleans. Boyd is a retired teacher with a 9-year-old grandson, one of thousands of Orleans Parish schoolchildren whose special education needs have not been sufficiently met under a 2015 settlement in the lawsuit P.B. v. Brumley. (Courtesy of Moving Challenges for Students with Disabilities)