When Monica Clarke began working at Alabama A&M University in Huntsville, she was looking for something, a calling, that she could bring to her work.

As the school’s service and learning coordinator, she was in contact with students daily, so she was in a prime position to not only be an observer but also an influencer on the young men and women at the college.

That was in 2016, almost three years after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down key portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in its Shelby County v. Holder decision. And what she found out about the students at A&M, a historically Black university, scared her.

“I’m gonna go out on a ledge and say over 90% of our students were not registered to vote,” Clarke said. “It was this huge wakeup call for me and others who were working with me. We were kind of shocked, kind of scared, kind of surprised – all of the above – and not just that they weren’t registered, but they didn’t even want to register. They had such a negative view of voter registration, of voting, of the government and police.”

That was when she became an activist for voting rights, growing the university’s voter registration service into a mission unto itself. And, as the nation notes the 10th anniversary of the Shelby decision this weekend, Clarke sees the same forces that created the need for the Voting Rights Act still threatening people of color.

“If, culturally, our students are coming to campus with the mindset that ‘my vote doesn’t matter’ or ‘it doesn’t matter, it’s not like they’re going to change anything,’ we have to educate them,” Clarke said. “Hopefully, they’ll learn something from us and take it back home. Now they educate mama and grandmama, because what I’ve learned is that if the students aren’t voting their parents aren’t voting.”

Close call

That education on a cultural level is important, especially in the South. Just as Shelby had its roots in Alabama, so did Allen v. Milligan, the basis for the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision earlier this month to throw out the state’s congressional district maps and have them redrawn to include a second district where white people are in the minority.

“With Shelby came the lack of some sort of oversight in these places that practice extreme discriminatory behavior, from the 1960s leading all the way up to today,” said Fred McBride, a senior adviser for voting rights at the Southern Poverty Law Center. “And now they’re just doing it without any oversight and it’s left up to groups like ours and others to challenge them. It’s just an onslaught of lawsuits.”

The Supreme Court’s decision on Milligan could be the first really good news that voting rights advocates have seen from the high court since the Shelby decision changed the legal landscape and opened a floodgate of new state laws with onerous voting restrictions. But the nearly 50-page dissenting opinion by Associate Justice Clarence Thomas tempers the celebration of the win. Writing for the minority, Thomas declares that the court’s majority used Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act – which protects against redistricting maps that dilute the voting strength of communities of color – as “a racial entitlement.”

In fact, Thomas wrote later in the dissent that Section 2 gave the government no authority to overturn diluted districts at all – a concept that came within one vote of undoing almost 60 years of progress toward more equitable elections.

“I didn’t read his opinion and I’m kind of glad,” Clarke said. “He tends to do something to my spirit sometimes. But I think young Black students need to understand what we are still fighting every single day.”

Educational challenges

In the decade since Shelby became the law of the land, advocates have learned that the best way to fight voter suppression is to empower the electorate. The effort to grow and educate voters is a constant one. And, according to McBride, the need for education on our electoral system and its limitations extends well beyond typical voters.

“I’m not really even sure how many politicians in these jurisdictions really, really understand redistricting – the rules that go into drawing these districts – and complying with the Voting Rights Act, equal protection, compactness, contiguity and keeping communities of interest intact,” McBride said. “I’m not sure they know all of this, because oftentimes over my 23 years of doing this I’ve had to explain to elected officials, as well as some of their demographers, what you can and cannot do. That’s just really kind of strange, but that’s the world we live in.”

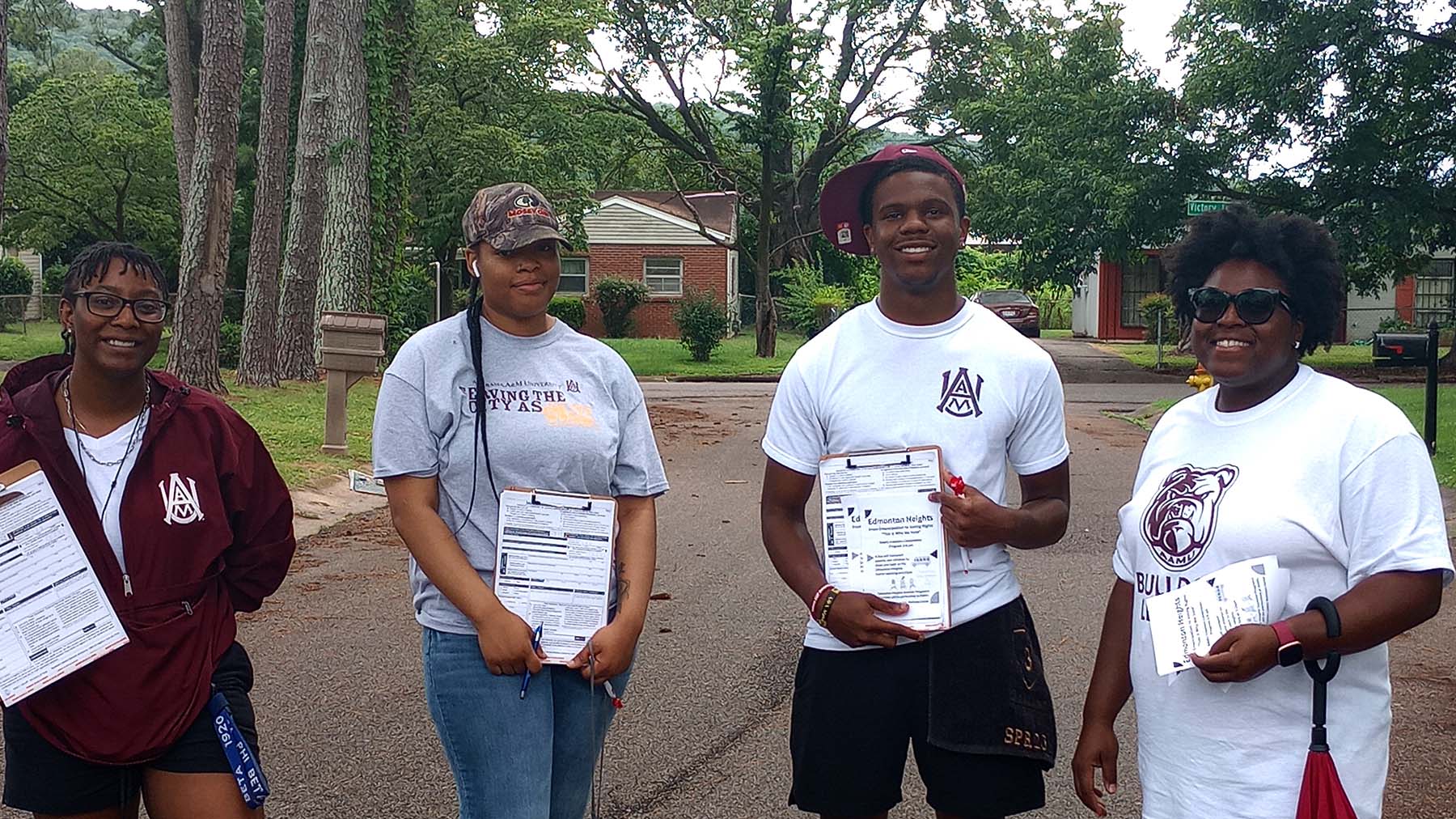

Clarke, along with students, volunteers and community partners, are hoping to address the problem at the grassroots end of the spectrum. Already this week, students and volunteers have been canvassing homes in Huntsville’s Edmonton Heights neighborhood, hoping to register non-voting members of the community. As part of that outreach, Alabama A&M sponsored a voter education rally on June 22, providing transportation for residents who wanted to learn more about voting rights and the challenges they face in Alabama. In addition to the speakers and presenters on election issues, the event featured performances by local children, a bounce house for children and other amusements to make it more attractive to young families.

And on June 24, the day before the anniversary of the Shelby County v. Holder decision, Clarke will take a group of students to the University of Montevallo in Shelby County to participate in an NAACP-sponsored “Shelby Democracy Restoration Summit” on voting rights. That three-day program kicks off today with a march and rally, features a full day of strategy sessions on June 24 and culminates on the anniversary day – June 25 – with an ecumenical worship service and gospel concert.

“The goal right now is to just get Alabama A&M down there so we can register people to vote there as well as have a seat at the table,” Clarke said.

A long, legally winding road

Even with strong commitments to enroll active voters and educate the next generation, the status quo can be a very hard stone to clear from democracy’s path. And the tool opponents have used most vigorously to fight against clearing that lane has been the electoral map, especially in the decade since the Shelby decision stripped the U.S. Department of Justice’s authority to restrain state and local gerrymandering under the Voting Rights Act.

Every 10 years, following the U.S. census, states and municipalities must redraw voting districts to reflect demographic changes. But advocates worry that some jurisdictions might want to redistrict more often after the political parties in power begin to lose elections.

“After next year, when there are some close [election] calls in some districts, some states may just engage in mid-decade redistricting to ensure the power doesn’t shift,” McBride said. “Now there seems to be a desire for some insurance that this district can only elect this particular kind of person and states will just engage in mid-decade redistricting and not even wait until the 2030 census.”

The Milligan decision is a pushback against the most egregious cases of disenfranchisement, specifically in Alabama. Only one of the state’s proposed seven congressional districts drawn after the 2020 census featured a Black majority, even though the state’s population is 27% Black.

In fact, the proportion of white people in Alabama decreased from 2010 to 2020 – from 68% to 64% – while the share of the Black population grew nearly 4%. An amicus “friend-of-the-court” brief that the SPLC filed with the Supreme Court on behalf of the nonprofit voter education and advocacy organization Stand-Up Mobile highlighted the fact that the state used the Alabama Gulf Coast as a “community of interest” to create a majority-white district while splitting up the state’s Black Belt region and diluting its Black voting power.

There was “no reason to prioritize the interests white Alabamians hold in common over the interests that both Black and white Alabamians in Mobile and the Black Belt face together each day,” according to the brief.

The Supreme Court’s ruling echoed this reasoning.

“I breathed a massive sigh of relief [when the Milligan decision was handed down], because we are living in the era of this post-Shelby County Roberts court,” said Jess Unger, a senior staff attorney with the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group. “Until this year, we had no indication that Chief Justice Roberts, and certainly not any other conservative justice, would not try to narrow voting rights at every opportunity.”

Unger also noted that the decision, while not a clear rebuttal of the court’s actions in the post-Shelby landscape, did not sound the death knell for Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

“For right now, at least we have Section 2,” Unger said. “There is really nothing new or positive, no new tools. It [Milligan] at least it does not make anything dramatically worse.”

‘Change that culture’

While voting rights advocates await the drop of the next shoe, Clarke is planning to continue her work to empower Alabama voters. So far, at least until COVID-19 disrupted the Alabama A&M campus, the numbers demonstrate that her efforts have been startlingly successful.

That 90% unregistered number she cites from 2016?

By 2020, it had been nearly reversed.

“We received a national award from the Students Learn Students Vote Coalition,” Clarke said. “We had reached up to 80% voter registration on campus. That was pretty cool. I mean, that was worth celebrating! We jumped up and down, screamed and yelled when we got that.”

The COVID-19 shutdowns and distance learning, however, have left a two-year gap in the program. With students largely studying from home, the outreach was at a standstill until the fall 2022 semester. But Clarke said the effort to pick up those students who were missed is underway and progressing, no matter what pitfalls may stand in the way.

“We have to change that culture,” Clarke said. “We have to become a culture where voting is a part of your educational process. That’s my goal. That’s what I’m working for.”

Photo at top: From left: Alabama A&M University students Alexis Powell, Marquishinae Walker, Miles Jernigan and Xantheia Walkins visit Huntsville’s Edmonton Heights neighborhood to register new voters. (Credit: Monica Clarke)