Florida activists oppose redevelopment plan that would displace residents again

Under the dome of St. Petersburg’s Tropicana Field, home to the Tampa Bay Rays baseball team, lies a field of broken dreams.

A Black neighborhood once lay where the stadium and its vast parking lots stand. Known as the Gas Plant District for the two immense fuel tanks that rose over it, this Florida community’s churches, homes and businesses were razed by bulldozers, the result of 1970s-era promises to revitalize the historically and culturally rich area with new housing and good jobs at a modern industrial park – then of the decision by city leaders in the 1980s to build a domed stadium to attract a Major League Baseball team.

By 1986, more than 280 buildings that once made up the Gas Plant neighborhood had been demolished. More than 500 families had been relocated. The sites of at least three former Black cemeteries, possibly with graves still underneath, had been paved over.

More than 30 businesses had closed or moved, and the neighborhoods within the Gas Plant District, known lovingly by residents – many of them descendants of the original Black settlers there – as Cooper’s Quarters, Methodist Town, Pepper Town, Sugar Hill, Jamestown and Little Egypt, were no more.

It was all billed as a community rebuild, paid for, in part, with $11.3 million in federal community redevelopment grants. But the rebuild never happened. Instead, the stadium initially known as the Florida Suncoast Dome went up and was later leased by the baseball team for the token sum of $1 a year. While the redevelopment grants did help some families buy better homes in other areas, neither the original project nor the $309 million baseball stadium that was eventually built made good on either the bulk of the affordable housing or the jobs that had been promised.

What happened to the Gas Plant District, once humming with the cacophony of cookouts, Black church services, grocery stores, jazz clubs – and also tenements, crime and vacant lots – is an old story in St. Petersburg, still one of the most racially segregated cities in the country. It is an old story across the nation, too, where bulldozers have torn through Black neighborhoods for generations, leaving Black communities from coast to coast with little more than abandoned promises.

Now the city of St. Petersburg appears determined to add another painful chapter to that old story. Last September, city officials announced a plan to sell the 86 acres that once made up the neighborhood to developers, part of a preliminary deal to build a new stadium to replace the aging and inadequate Tropicana Field. The mayor of St. Petersburg, Ken Welch – who traces his roots back to the Gas Plant community – calls the plan, despite its inclusion of only about 10% affordable housing, an unprecedented opportunity to do right by Black residents.

In the video: Community members address the redevelopment of one of St. Petersburg, Florida’s, oldest Black communities, the Gas Plant District.

A coalition of community groups, though, is crying foul. They say that as currently written, the plan to build a new stadium at an estimated cost of $1.3 billion, about half of which is to be shouldered by taxpayers, not only fails to address the racial inequities of the past but will harm Black residents today.

As the community organizations ready their response, they are receiving support from the Community Justice Project (CJP), a Miami-based nonprofit whose team of lawyers collaborates with grassroots organizers in low-income communities of color to promote racial and economic justice.

Now, the Southern Poverty Law Center is joining with them to investigate the history of how the city first acquired the land; how federal, state and local entities used the powers of eminent domain in the name of economic development; and how that development failed to produce sustainable employment or affordable housing.

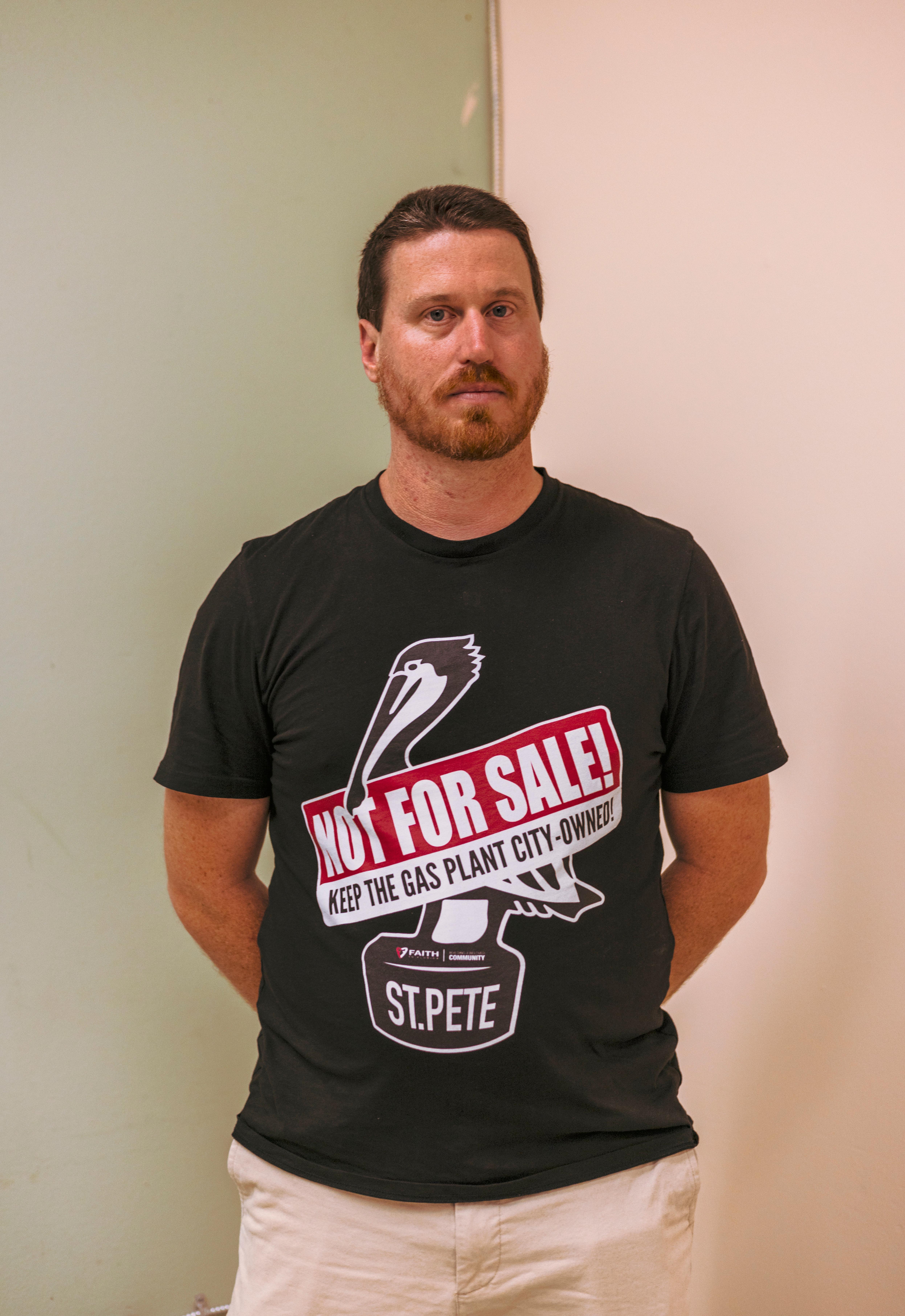

“The city has done a great job of outwardly saying, we should address racial equity and racial harms of the past,” said Nick Carey, lead organizer with Faith in Florida, the economic and social justice organization leading a campaign to rework the project. “What we are saying is, the actual plan that you have come up with doesn’t match those words. Not everything in this plan is bad, but this entire redevelopment is based on an idea of trickle-down economics that has been long since disproven to benefit folks and actively harms folks that make $20 an hour. It’s great for the city to say we want to honor the history of the historic Gas Plant neighborhood, but if Black folks can’t afford to live there, then what are we talking about?”

Generational wealth stripped

The SPLC is looking into whether there is a way to stop a city that acquired a valuable swath of property from profiting again, a generation later, on promises it didn’t keep the first time.

“We are concerned that the city used federal funding to take land for a particular purpose, and that purpose has not been realized,” said Kirsten Anderson, deputy legal director of the SPLC’s Economic Justice litigation team. “Economic redevelopment didn’t happen here. Jobs weren’t created here in a meaningful way. The community was told they would be moved out temporarily, then moved back into an area reconfigured with better services, and they never were.

“The generational wealth of this community was the land, and that has been stripped from it,” Anderson said. “Now the city is planning to sell this incredibly valuable land for less than market value to a development company. That is a continuing violation of the original harm that will further retrench racial discrimination.”

As part of its partnership, the SPLC has collaborated with CJP to sponsor local forums for community members to voice their concerns.

“Far too often, Black communities that have served to create the cultural fabric of cities are overlooked and left voiceless in the pursuit of progress,” CJP Senior Staff Attorney Berbeth Foster said. “It is vital that we amplify their voices and allow them to define what progress means for their families and communities. The descendants of the historic Gas Plant neighborhood have made it clear that ballparks and luxury residences do not serve their needs.”

Attorneys for the SPLC and CJP are working together to support Faith in Florida and other community groups in their demands that the land continue to be city-owned, and that development include mixed-income housing affordable to people making 50% or less of the area’s median income, along with Black- and Brown-owned business opportunities and the use of union labor and environmental protections. As part of their work together, the SPLC and CJP will lift up stories about real people in the community to humanize their struggle for racial and economic justice.

“We are working to make sure that economic development actually includes communities of color, because too often, redevelopment of these communities is equivalent to their displacement,” Anderson said.

‘Fall like dominoes’

The rich cultural wealth of the Gas Plant neighborhood, as in other predominantly Black communities all over the U.S., was born of segregationist policies that made it difficult for Black families to buy homes, send their children to school and even, in many cases, safely frequent more affluent, exclusive areas of American towns and cities.

As in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Eatonville, Florida, New York City’s Harlem and hundreds of other municipalities, Black residents coped with the pain of that exclusion by making their own neighborhoods into havens – tight-knit communities with stores they could frequent without fear, churches where they could lift their voices and neighbors they could count on.

Alexa Manning, 64, a retired physical education teacher who has lived most of her life in this Gulf Coast community, remembers the Gas Plant neighborhood as a beloved part of her childhood. As a young girl, she and her brothers would ride their bicycles through the neighborhood on weekends, past family fish fries and barbecues, businesses, schools, theaters and churches in what she remembers as a self-contained “small city, a sustainable Black city, in the middle of a larger city.”

The neighborhood was also pocked with poverty, Manning and others recalled. Some homes were shacks. Many apartment buildings were ill-maintained. Swaths of the area had fallen victim to cycles of neglect.

Ultimately, many of the city’s Black leaders and Black community organizations endorsed the city’s plans for the area, convinced by pledges that the project would lead to investment in housing, in jobs and in the needs of underserved people. And, indeed, some families forced to move prospered elsewhere, in bigger homes with bigger yards and better schools.

But most of the promises were broken. The subsuming of the Gas Plant community, one of the oldest Black neighborhoods in St. Petersburg, under the girders and concrete of a stadium and parking lots became seen as emblematic of the way Black culture has been buried across the sweep of U.S. history.

“I was in my teens when the neighborhood was destroyed,” Manning said. “I know people were promised money by the city to relocate. How much of that happened, I’m not sure. They were caught in their weakest moment. I think what they started at the Gas Plant was just the beginning. It is all designed just to fall like dominoes, that we were always going to be pushed. They started pushing us out then, and I think they haven’t stopped pushing us out yet.”

When Manning heard about the city’s new plan, “I could not understand how this was happening again,” she said. “We have lived in this city our whole lives. We are teachers. We are counselors, we are people who give back to this city, and to me this is like a slap in the face. You have not put one cent into our communities and now you’re just taking again? I need to understand why we are still not a part of this city. You are building everything around us, but not for us.”

‘Crumbs’ for the community

City leaders have stood by the plan. The proposal involves redeveloping the entire 86-acre Gas Plant District. The redevelopment terms cover two areas – about 17 to 20 acres for a new, 30,000-seat, fixed-roof stadium, parking lots and infrastructure, and a 20-year redevelopment plan for the remaining acres of the district surrounding it. Under the plan, the baseball team would contribute more than half the cost to build the stadium, about $700 million, and the city of St. Petersburg and Pinellas County would contribute $600 million, paid for through bonds and a 6% tax on accommodations on hotels and private homes rented for less than six months.

The surrounding Gas Plant District redevelopment, being paid for by a private development company, is slated to include 4,800 market-rate residences, 1.4 million square feet of office space, 750,000 square feet of retail space, a 100,000-square-foot conference center, and a 750-room hotel – plus a small museum devoted to Black history. All told the project, including the stadium construction and the cost to redevelop the rest of the Gas Plant District, is estimated by the city at $6.5 billion.

The developers have promised to pitch in $50 million to help revitalize the surrounding neighborhood, including 600 new affordable and workforce housing units on the acreage and another 600 off-site. Not only is that inadequate, Anderson of the SPLC said, but with little to no enforcement mechanism and only the faintest of penalties for noncompliance, the development plan as proposed almost encourages the developer not to follow through.

Urgent action is needed to fight the plan. On Feb. 6, the city’s Community Benefits Advisory Council (CBAC) is scheduled to vote on whether to recommend moving forward with it. The plan would then be put to a vote by the St. Petersburg City Council. Faith in Florida is circulating a petition against it.

“CBAC is the community’s best hope at placing enforcement and accountability at the forefront of this plan,” Foster said. “Without prioritizing affordable housing and including stiff penalties for failure to comply with the agreement, the developer’s promises are not worth the paper it is written on.”

In the video: A plan to build a new, $1.3 billion stadium in St. Petersburg, Florida, is “one of the worst insults to the ancestry of the Gas Plant and the present-day citizens of St. Petersburg,” says Bishop Manuel Sykes, pastor of the Bethel Community Baptist Church.

Bethel Community Baptist Church, a pillar of the south St. Petersburg community since 1923, once sat at the center of the Gas Plant neighborhood but had to move to a new building when the original church came down as part of the stadium development. Its pastor, Bishop Manuel Sykes, calls the new city plan “unethical and immoral.”

The affordable housing that is part of the plan, Sykes said, represents “crumbs” for a community whose valuable land was taken away and now is being sold for less than market value. And it does little to address the housing crisis in St. Petersburg, fueled by soaring rents and a shortage of reasonably priced rental properties.

“We have a housing crisis for workforce and middle- to low-income people, and yet they are building luxury apartments and condos at a rate that’s leaving some of them empty,” Sykes said. “How do you justify creating that glut of housing for the affluent and ignore the population that lived in that place and simply act as though their voices don’t matter? This is about the destruction and displacement of African American communities everywhere.”

Photo at top: Activist Dylan Dames at a meeting hosted by Faith in Florida to discuss St. Petersburg’s plans to build a new stadium in the Gas Plant District. (Credit: Saul Martinez)